What Makes an Elite Equestrian Rider?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

138904 02 Classic.Pdf

breeders’ cup CLASSIC BREEDERs’ Cup CLASSIC (GR. I) 30th Running Santa Anita Park $5,000,000 Guaranteed FOR THREE-YEAR-OLDS & UPWARD ONE MILE AND ONE-QUARTER Northern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 122 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs.; Southern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 117 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs. All Fillies and Mares allowed 3 lbs. Guaranteed $5 million purse including travel awards, of which 55% of all monies to the owner of the winner, 18% to second, 10% to third, 6% to fourth and 3% to fifth; plus travel awards to starters not based in California. The maximum number of starters for the Breeders’ Cup Classic will be limited to fourteen (14). If more than fourteen (14) horses pre-enter, selection will be determined by a combination of Breeders’ Cup Challenge winners, Graded Stakes Dirt points and the Breeders’ Cup Racing Secretaries and Directors panel. Please refer to the 2013 Breeders’ Cup World Championships Horsemen’s Information Guide (available upon request) for more information. Nominated Horses Breeders’ Cup Racing Office Pre-Entry Fee: 1% of purse Santa Anita Park Entry Fee: 1% of purse 285 W. Huntington Dr. Arcadia, CA 91007 Phone: (859) 514-9422 To Be Run Saturday, November 2, 2013 Fax: (859) 514-9432 Pre-Entries Close Monday, October 21, 2013 E-mail: [email protected] Pre-entries for the Breeders' Cup Classic (G1) Horse Owner Trainer Declaration of War Mrs. John Magnier, Michael Tabor, Derrick Smith & Joseph Allen Aidan P. O'Brien B.c.4 War Front - Tempo West by Rahy - Bred in Kentucky by Joseph Allen Flat Out Preston Stables, LLC William I. -

Introduction to Russian Poetry - Michael Wachtel Excerpt More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521004934 - The Cambridge Introduction to Russian Poetry - Michael Wachtel Excerpt More information Introduction Поэ´т – издaлeкa´ зaво´дит рe´чь. Поэ´тa – дaлeко´ зaво´дит рe´чь. цвeтaeвa, «Поэ´ты» The poet brings language from afar. Language brings the poet far. Tsvetaeva, “Poets” When poets read their works aloud, we may not understand every word, but we immediately recognize that their intonation differs from that of everyday speech. This “unnatural” declamation often causes confusion among those who first encounter it. “Why don’t they just read it normally?” one is tempted to ask. The reason is simple: poets want to set their speech off from everyday language. Individual poets vary widely in the degree of “unnaturalness” they introduce to their readings, but in virtually all cases their goal is the same: to destabilize the familiar world of their listeners, to make them hear anew. All of us, poets or not, alter our tone of voice and choice of words in accordance with specific circumstances. We speak differently with our par- ents than with our peers, we address the auto mechanic differently than the policeman, we speak differently when giving a toast than we do when calling for an ambulance. In many life situations, what might be called the prosaic attitude toward language dominates. Our object is to relay information as quickly and unambiguously as possible. At other times, getting the point across is not enough; it is essential to do so convincingly and fervently. We select our words carefully and consciously organize them. In this case, we are not necessarily creating poetry, but it is fair to say that we are moving in the direction of poetry. -

The History of International Equestrian Sports

“... and Allah took a handful of Southerly wind... and created the horse” The history of international equestrian sports Susanna Hedenborg Department of Sport Sciences, Malmö University Published on the Internet, www.idrottsforum.org/hedenborg140613, (ISSN 1652–7224), 2014-06-13 Copyright © Susanna Hedenborg 2014. All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the author. The aim of this paper is to chart the relationship between men, women and horses with focus on equestrian sports. The degree of internationality of these sports, as well as the question of whether a sport can be seen as international if only men or women participate, are discussed. Furthermore, the diffusion of equestrian sports are presented; in short, equestrian activities spread interna- tionally in different directions up until the late 19th century. Since then Olympic Equestrian events (dressage, show jumping and eventing) have been diffused from Europe. Even though men and women are allowed to compete against each other in the equestrian events, the number of men and women varies widely, irrespective of country, and until this imbalance is redressed, equestrian sports cannot be seen as truly international. SUSANNA HEDENBORG iis professor of sport studies at Malmö University, Sweden. Her research focuses on sport history as well as on issues of gender and age. Currently she is working with the international history of equestrian sports, addressing the interchangeable influences of gender, age and nationality. -

Horse Sale Update

Jann Parker Billings Livestock Commission Horse Sales Horse Sale Manager HORSE SALE UPDATE August/September 2021 Summer's #1 Show Headlined by performance and speed bred horses, Billings Livestock’s “August Special Catalog Sale” August 27-28 welcomed 746 head of horses and kicked off Friday afternoon with a UBRC “Pistols and Crystals” tour stop barrel race and full performance preview. All horses were sold on premise at Billings Live- as the top two selling draft crosses brought stock with the ShowCase Sale Session entries $12,500 and $12,000. offered to online buyers as well. Megan Wells, Buffalo, WY earned the The top five horses averaged $19,600. fast time for a BLS Sale Horse at the UBRC Gentle ruled the day Barrel Race aboard her con- and gentle he was, Hip 185 “Ima signment Hip 106 “Doc Two Eyed Invader” a 2009 Billings' Triple” a 2011 AQHA Sorrel AQHA Bay Gelding x Kis Battle Gelding sired by Docs Para- Song x Ki Two Eyed offered Loose Market On dise and out of a Triple Chick by Paul Beckstead, Fairview, bred dam. UT achieved top sale position Full Tilt A consistant 1D/ with a $25,000 sale price. 486 Offered Loose 2D barrel horse, the 16 hand The Beckstead’s had gelding also ran poles, and owned him since he was a foal Top Loose $6,800 sold to Frank Welsh, Junction and the kind, willing, all-around 175 Head at $1,000 or City OH for $18,000. gelding was a finished head, better Affordability lives heel, breakaway horse as well at Billings, too, where 69 head as having been used on barrels, 114 Head at $1,500+ of catalog horses brought be- poles, trails, and on the ranch. -

HOW WE GOT HERE I Imagine If You Are Reading This, We Share Something in Common--The Love of Horses and Horse Racing

FRIDAY, APRIL 5, 2019 TAKING STOCK: OP/ED: NEVER LET A GOOD CRISIS GO TO WASTE by Boyd Browning HOW WE GOT HERE I imagine if you are reading this, we share something in common--the love of horses and horse racing. Like me, you may even make your living and provide for family by working in this industry. When I get the TDN Alerts at night that another important governing body is calling for an end to racing or to shut down the track, I feel sick to my stomach and can't sleep. And then I get up in the morning and read/listen to the finger pointing and infighting within the industry. The "blame game" must stop immediately and we can either work together to make smart decisions that reflect the world we live in and survive, or we can continue to fight with one another about who's right and who's wrong. We must recognize and embrace meaningful change to protect and care for the horse. Cont. p3 IN TDN EUROPE TODAY Is the future of the American dirt horse at a crossroads? | Coady CUNNINGHAM–A REBEL IN THE RANKS Alayna Cullen chats with Rebel Racing’s Phil Cunningham about new stallion Rajasinghe (GB) (Choisir {Aus}). Click or tap by Sid Fernando here to go straight to TDN Europe. The American dirt horse is tough, strong, and fast. He's an athlete. He's a combination of speed and stamina, bred to race on an unforgivingly hard surface, bred to race at two, bred to break quickly from the gate, bred to run hard early, bred to withstand pressure late. -

1 June 27 – July 1, 1977 7-C Dr. Reams Biological Theory Of

June 27 – July 1, 1977 7-C Dr. Reams Biological Theory of Ionization Dr. John Black & Doc. Reams Tape 1 – Side A God never repairs a damaged cell. Never! He throws it out and puts a brand-new one in its place. God is not in the second-hand parts business. You are made out of brand-new parts. You should keep them brand-new. Keep your vim, vigor and vitality for many, many years. And you know most people live no longer than they plan to live. They start early planning to live, plotting their life and their diet and their habits. Life would be different. You know, it’s the easiest thing in the world to be healthy. It’s the easiest thing in the world to be healthy. To be sick you got to work at it. You’ve got to break all the rules. You’ve got to get hooked on something, or inhibited by it, or tied to it. Variety is the spice of life. In a great variety there is safety. So what I am trying to tell you, this is what the Bible message is about. It is, heal the sick. Heal the sick. God wants you to heal the sick. And some people think, oh that’s just to be done instantaneously. Never, never, with diet or anything else. Do you know that the health message starts in the very first chapter of Genesis? The 28th verse. The very first chapter of Genesis in the 28th verse. We are going to have a lot more to say about that as the week goes on. -

Proceedings of the 1St International Equitation Science Symposium 2005

Proceedings of the 1st International Equitation Science Symposium 2005 Friday 26th and Saturday 27th August, 2005 Australian Equine Behaviour Centre, Melbourne, Australia. Editors: P. McGreevy, A. McLean, A. Warren-Smith, D. Goodwin, N. Waran i Organising Committee: S. Botterrill, A. McLean, A. Warren-Smith, D. Goodwin, N. Waran, P. McGreevy Contact: Australian Equine Behaviour Centre, Clonbinane, Broadford, VIC 3569, Australia. Email: [email protected] ISBN: ii Contents Page Timetable 1 Welcome 2 The evolution of schooling principles and their influence on the 4 horse’s welfare Ödberg FO Defining the terms and processes associated with equitation 10 McGreevy PD, McLean AN, Warren-Smith AK, Waran N and Goodwin D A low cost device for measuring the pressures exerted on domestic 44 horses by riders and handlers. Warren-Smith AK, Curtis RA and McGreevy PD Breed differences in equine retinae 56 Evans KE and McGreevy PD Equestrianism and horse welfare: The need for an ‘equine-centred’ 67 approach to training. Waran N The use of head lowering in horses as a method of inducing calmness. 75 Warren-Smith AK and McGreevy PD Epidemiology of horses leaving the Thoroughbred and Standardbred 84 racing industries Hayek AR, Jones B, Evans DL, Thomson PC and McGreevy PD A preliminary study on the relation between subjectively assessing 89 dressage performances and objective welfare parameters de Cartier d’Yves A and Ödberg FO Index 111 iii Timetable Friday 26th Activity Presenters August Registration: Tea/coffee on arrival at the Australian Equine -

PHYSICAL HANDICAPPING Steve Thygersen December 14, 2011

PHYSICAL HANDICAPPING Steve Thygersen December 14, 2011 OVERALL APPEARANCE The ideal horse is well proportioned, alert without being fixated, has a beautiful shiny coat with dappling and there is a spring in their step and their head is high and neck bowed. It doesn’t hurt when they are playful as well – giving the groom a face full of nose or nipping at their pony and then jumping back. Horses like to play, and young horses really like to play. If you are playful, you aren’t scared of the upcoming race, in fact you are ready to roll. I see trainers all the time try to get them to stop being playful and I always think “shouldn’t this be fun for them?”. One of the most playful horses I ever saw was Majestic Prince back in the late 60s – he seemed to take great pleasure in getting Johnny Longden to bust a gasket. The second you turned your back on him he would slyly start sneaking away. He almost got away on the day of the Santa Anita Derby but Longden turned to him and bellowed “Don’t even think about it!” He stopped dead in his tracks and waited for them to come get him. He also liked to grab Longden by the back of the pants and lift his head up. The only horse I know that delighted in giving Melvins. The point is a playful horse is a happy horse and happy horses run. COAT, MANE AND TAIL The eyes may be the windows to the soul, but the coat is the mirror of their physical condition. -

Nottingham Horseball Club Player Handbook

Nottingham Horseball Club Nottingham Horseball Club Player Handbook http://nottinghamhorseballclub.btck.co.uk Face Book: Nottingham-Arkenfield Horseball-club 1 Nottingham Horseball Club Index 1 WELCOME ...................................................................................................................................... 3 2 SELECTION AND RESERVES ....................................................................................................... 4 3 PRACTICING - PRACTICE MAKES PERFECT! .......................................................................... 5 3.1 WINTER : ..................................................................................................................................... 5 3.2 SPRING : ...................................................................................................................................... 5 3.3 SUMMER : .................................................................................................................................... 5 3.4 COMPETITIONS : ........................................................................................................................... 5 3.5 TEAM TRAINING : .......................................................................................................................... 5 4 FINANCE ......................................................................................................................................... 6 4.1 COSTS ....................................................................................................................................... -

A Commercial Guide to Eventing at the National Level

BRITISH EVENTING A COMMERCIAL GUIDE TO EVENTING AT THE NATIONAL LEVEL 3 CONTENTS Guide overview ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 What makes eventing’s national calendar of events so special?........................................................................................................................... 5 Eventing explained......................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 6-9 What makes eventing stand out?............................................................................................................................................................................................ 10-11 Eventing’s commercial appeal ................................................................................................................................................................................................. 13 Audience profiles ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 14-15 Engaging with audiences .......................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Age-Related Changes in the Behaviour of Domestic Horses As Reported by Owners

animals Article Age-Related Changes in the Behaviour of Domestic Horses as Reported by Owners Bibiana Burattini 1,*, Kate Fenner 1 , Ashley Anzulewicz 1, Nicole Romness 1, Jessica McKenzie 2, Bethany Wilson 1 and Paul McGreevy 1 1 Sydney School of Veterinary Science, Faculty of Science, University of Sydney, Camperdown, NSW 2006, Australia; [email protected] (K.F.); [email protected] (A.A.); [email protected] (N.R.); [email protected] (B.W.); [email protected] (P.M.) 2 School of Life and Environmental Sciences, Faculty of Science, University of Sydney, Camperdown, NSW 2006, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-409-326-343 Received: 16 November 2020; Accepted: 3 December 2020; Published: 7 December 2020 Simple Summary: Some treatments for common problem behaviours in domestic horses can compromise horse welfare. Such behaviours can be the manifestation of pain, confusion and conflict. In contrast, among the desirable attributes in horses, boldness and independence are two important behavioural traits that affect the fearfulness, assertiveness and sociability of horses when interacting with their environment, objects, conspecifics and humans. Shy and socially dependent horses are generally more difficult to manage and train than their bold and independent counterparts. Previous studies have shown how certain basic temperament traits predict the behavioural output of horses, but few have investigated how the age of the horse and the age it was when started being trained under saddle affect behaviour. Using 1940 responses to the Equine Behaviour Assessment and Research Questionnaire (E-BARQ), the current study explored the behavioural evidence of boldness and independence in horses and how these related to the age of the horse. -

2008 File1lined.Vp

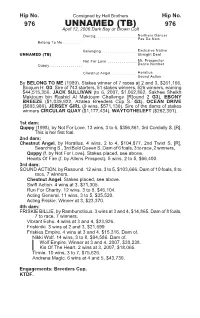

Hip No. Consigned by Hall Brothers Hip No. 976 UNNAMED (TB) 976 April 12, 2006 Dark Bay or Brown Colt Danzig .....................Northern Dancer Pas De Nom Belong To Me .......... Belonging ..................Exclusive Native UNNAMED (TB) Straight Deal Not For Love ...............Mr. Prospector Quppy................. Dance Number Chestnut Angel .............Horatius Sound Action By BELONG TO ME (1989). Stakes winner of 7 races at 2 and 3, $261,166, Boojum H. G3. Sire of 743 starters, 51 stakes winners, 526 winners, earning $44,515,356, JACK SULLIVAN (to 6, 2007, $1,062,862, Sakhee Sheikh Maktoum bin Rashid Al Maktoum Challenge [R]ound 2 G3), EBONY BREEZE ($1,039,922, Azalea Breeders Cup S. G3), OCEAN DRIVE ($803,986), JERSEY GIRL (9 wins, $571,136). Sire of the dams of stakes winners CIRCULAR QUAY ($1,177,434), WAYTOTHELEFT ($262,391). 1st dam: Quppy (1998), by Not For Love. 13 wins, 3 to 6, $356,861, 3rd Cordially S. [R]. This is her first foal. 2nd dam: Chestnut Angel, by Horatius. 4 wins, 2 to 4, $104,877, 2nd Twixt S. [R], Searching S., 3rd Bold Queen S. Dam of 6 foals, 3 to race, 2 winners, Quppy (f. by Not For Love). Stakes placed, see above. Hearts Of Fire (f. by Allens Prospect). 5 wins, 2 to 5, $66,400. 3rd dam: SOUND ACTION, by Resound. 12 wins, 3 to 5, $103,666. Dam of 10 foals, 8 to race, 7 winners, Chestnut Angel. Stakes placed, see above. Swift Action. 4 wins at 3, $71,305. Run For Charity. 12 wins, 3 to 8, $46,104.