Introduction to Russian Poetry - Michael Wachtel Excerpt More Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

138904 02 Classic.Pdf

breeders’ cup CLASSIC BREEDERs’ Cup CLASSIC (GR. I) 30th Running Santa Anita Park $5,000,000 Guaranteed FOR THREE-YEAR-OLDS & UPWARD ONE MILE AND ONE-QUARTER Northern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 122 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs.; Southern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 117 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs. All Fillies and Mares allowed 3 lbs. Guaranteed $5 million purse including travel awards, of which 55% of all monies to the owner of the winner, 18% to second, 10% to third, 6% to fourth and 3% to fifth; plus travel awards to starters not based in California. The maximum number of starters for the Breeders’ Cup Classic will be limited to fourteen (14). If more than fourteen (14) horses pre-enter, selection will be determined by a combination of Breeders’ Cup Challenge winners, Graded Stakes Dirt points and the Breeders’ Cup Racing Secretaries and Directors panel. Please refer to the 2013 Breeders’ Cup World Championships Horsemen’s Information Guide (available upon request) for more information. Nominated Horses Breeders’ Cup Racing Office Pre-Entry Fee: 1% of purse Santa Anita Park Entry Fee: 1% of purse 285 W. Huntington Dr. Arcadia, CA 91007 Phone: (859) 514-9422 To Be Run Saturday, November 2, 2013 Fax: (859) 514-9432 Pre-Entries Close Monday, October 21, 2013 E-mail: [email protected] Pre-entries for the Breeders' Cup Classic (G1) Horse Owner Trainer Declaration of War Mrs. John Magnier, Michael Tabor, Derrick Smith & Joseph Allen Aidan P. O'Brien B.c.4 War Front - Tempo West by Rahy - Bred in Kentucky by Joseph Allen Flat Out Preston Stables, LLC William I. -

Poetry Sampler

POETRY SAMPLER 2020 www.academicstudiespress.com CONTENTS Voices of Jewish-Russian Literature: An Anthology Edited by Maxim D. Shrayer New York Elegies: Ukrainian Poems on the City Edited by Ostap Kin Words for War: New Poems from Ukraine Edited by Oksana Maksymchuk & Max Rosochinsky The White Chalk of Days: The Contemporary Ukrainian Literature Series Anthology Compiled and edited by Mark Andryczyk www.academicstudiespress.com Voices of Jewish-Russian Literature An Anthology Edited, with Introductory Essays by Maxim D. Shrayer Table of Contents Acknowledgments xiv Note on Transliteration, Spelling of Names, and Dates xvi Note on How to Use This Anthology xviii General Introduction: The Legacy of Jewish-Russian Literature Maxim D. Shrayer xxi Early Voices: 1800s–1850s 1 Editor’s Introduction 1 Leyba Nevakhovich (1776–1831) 3 From Lament of the Daughter of Judah (1803) 5 Leon Mandelstam (1819–1889) 11 “The People” (1840) 13 Ruvim Kulisher (1828–1896) 16 From An Answer to the Slav (1849; pub. 1911) 18 Osip Rabinovich (1817–1869) 24 From The Penal Recruit (1859) 26 Seething Times: 1860s–1880s 37 Editor’s Introduction 37 Lev Levanda (1835–1888) 39 From Seething Times (1860s; pub. 1871–73) 42 Grigory Bogrov (1825–1885) 57 “Childhood Sufferings” from Notes of a Jew (1863; pub. 1871–73) 59 vi Table of Contents Rashel Khin (1861–1928) 70 From The Misfit (1881) 72 Semyon Nadson (1862–1887) 77 From “The Woman” (1883) 79 “I grew up shunning you, O most degraded nation . .” (1885) 80 On the Eve: 1890s–1910s 81 Editor’s Introduction 81 Ben-Ami (1854–1932) 84 Preface to Collected Stories and Sketches (1898) 86 David Aizman (1869–1922) 90 “The Countrymen” (1902) 92 Semyon Yushkevich (1868–1927) 113 From The Jews (1903) 115 Vladimir Jabotinsky (1880–1940) 124 “In Memory of Herzl” (1904) 126 Sasha Cherny (1880–1932) 130 “The Jewish Question” (1909) 132 “Judeophobes” (1909) 133 S. -

Nostalgia and the Myth of “Old Russia”: Russian Émigrés in Interwar Paris and Their Legacy in Contemporary Russia

Nostalgia and the Myth of “Old Russia”: Russian Émigrés in Interwar Paris and Their Legacy in Contemporary Russia © 2014 Brad Alexander Gordon A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion Of the Bachelor of Arts degree in International Studies at the Croft Institute for International Studies Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College The University of Mississippi University, Mississippi April, 2014 Approved: Advisor: Dr. Joshua First Reader: Dr. William Schenck Reader: Dr. Valentina Iepuri 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………p. 3 Part I: Interwar Émigrés and Their Literary Contributions Introduction: The Russian Intelligentsia and the National Question………………….............................................................................................p. 4 Chapter 1: Russia’s Eschatological Quest: Longing for the Divine…………………………………………………………………………………p. 14 Chapter 2: Nature, Death, and the Peasant in Russian Literature and Art……………………………………………………………………………………..p. 26 Chapter 3: Tsvetaeva’s Tragedy and Tolstoi’s Triumph……………………………….........................................................................p. 36 Part II: The Émigrés Return Introduction: Nostalgia’s Role in Contemporary Literature and Film……………………………………………………………………………………p. 48 Chapter 4: “Old Russia” in Contemporary Literature: The Moral Dilemma and the Reemergence of the East-West Debate…………………………………………………………………………………p. 52 Chapter 5: Restoring Traditional Russia through Post-Soviet Film: Nostalgia, Reconciliation, and the Quest -

Toronto Slavic Quarterly. № 33. Summer 2010

Michael Basker The Trauma of Exile: An Extended Analysis of Khodasevich’s ‘Sorrentinskie Fotografii’ What exile from himself can flee Byron1 It is widely accepted that the deaths in August 1921 of Aleksandr Blok and Nikolai Gumilev, the one ill for months and denied until too late the necessary papers to leave Russia for treatment, the other executed for complicity in the so-called Tag- antsev conspiracy, marked a practical and symbolic turning point in the relations between Russian writers and thinkers and the new regime. In the not untypical assessment of Vladislav Khoda- sevich’s long-term partner in exile, Nina Berberova: …that August was a boundary line. An age had begun with the ‘Ode on the Taking of Khotin’ (1739) and had ended with Au- gust 1921: all that came afer (for still a few years) was only the continuation of this August: the departure of Remizov and Bely abroad, the departure of Gorky, the mass exile of the intelligent- sia in the summer of 1922, the beginning of planned repres- sions, the destruction of two generations — I am speaking of a two-hundred year period of Russian literature. I am not saying that it had all ended, but that an age of it had.2 © Maichael Basker, 2010 © TSQ 33. Summer 2010 (http://www.utoronto.ca/tsq/) 1 From ‘To Inez’, song inserted between stanzas lxxiv and lxxxv of Canto 1 of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage. To avoid undue encumbrance of the extensive crit- ical apparatus, works of nineteenth and twentieth-century poetry by authors other than Khodasevich will generally be identified by title or first line, and cited without reference to the standard academic editions from which they have been taken. -

Horse Sale Update

Jann Parker Billings Livestock Commission Horse Sales Horse Sale Manager HORSE SALE UPDATE August/September 2021 Summer's #1 Show Headlined by performance and speed bred horses, Billings Livestock’s “August Special Catalog Sale” August 27-28 welcomed 746 head of horses and kicked off Friday afternoon with a UBRC “Pistols and Crystals” tour stop barrel race and full performance preview. All horses were sold on premise at Billings Live- as the top two selling draft crosses brought stock with the ShowCase Sale Session entries $12,500 and $12,000. offered to online buyers as well. Megan Wells, Buffalo, WY earned the The top five horses averaged $19,600. fast time for a BLS Sale Horse at the UBRC Gentle ruled the day Barrel Race aboard her con- and gentle he was, Hip 185 “Ima signment Hip 106 “Doc Two Eyed Invader” a 2009 Billings' Triple” a 2011 AQHA Sorrel AQHA Bay Gelding x Kis Battle Gelding sired by Docs Para- Song x Ki Two Eyed offered Loose Market On dise and out of a Triple Chick by Paul Beckstead, Fairview, bred dam. UT achieved top sale position Full Tilt A consistant 1D/ with a $25,000 sale price. 486 Offered Loose 2D barrel horse, the 16 hand The Beckstead’s had gelding also ran poles, and owned him since he was a foal Top Loose $6,800 sold to Frank Welsh, Junction and the kind, willing, all-around 175 Head at $1,000 or City OH for $18,000. gelding was a finished head, better Affordability lives heel, breakaway horse as well at Billings, too, where 69 head as having been used on barrels, 114 Head at $1,500+ of catalog horses brought be- poles, trails, and on the ranch. -

HOW WE GOT HERE I Imagine If You Are Reading This, We Share Something in Common--The Love of Horses and Horse Racing

FRIDAY, APRIL 5, 2019 TAKING STOCK: OP/ED: NEVER LET A GOOD CRISIS GO TO WASTE by Boyd Browning HOW WE GOT HERE I imagine if you are reading this, we share something in common--the love of horses and horse racing. Like me, you may even make your living and provide for family by working in this industry. When I get the TDN Alerts at night that another important governing body is calling for an end to racing or to shut down the track, I feel sick to my stomach and can't sleep. And then I get up in the morning and read/listen to the finger pointing and infighting within the industry. The "blame game" must stop immediately and we can either work together to make smart decisions that reflect the world we live in and survive, or we can continue to fight with one another about who's right and who's wrong. We must recognize and embrace meaningful change to protect and care for the horse. Cont. p3 IN TDN EUROPE TODAY Is the future of the American dirt horse at a crossroads? | Coady CUNNINGHAM–A REBEL IN THE RANKS Alayna Cullen chats with Rebel Racing’s Phil Cunningham about new stallion Rajasinghe (GB) (Choisir {Aus}). Click or tap by Sid Fernando here to go straight to TDN Europe. The American dirt horse is tough, strong, and fast. He's an athlete. He's a combination of speed and stamina, bred to race on an unforgivingly hard surface, bred to race at two, bred to break quickly from the gate, bred to run hard early, bred to withstand pressure late. -

1 June 27 – July 1, 1977 7-C Dr. Reams Biological Theory Of

June 27 – July 1, 1977 7-C Dr. Reams Biological Theory of Ionization Dr. John Black & Doc. Reams Tape 1 – Side A God never repairs a damaged cell. Never! He throws it out and puts a brand-new one in its place. God is not in the second-hand parts business. You are made out of brand-new parts. You should keep them brand-new. Keep your vim, vigor and vitality for many, many years. And you know most people live no longer than they plan to live. They start early planning to live, plotting their life and their diet and their habits. Life would be different. You know, it’s the easiest thing in the world to be healthy. It’s the easiest thing in the world to be healthy. To be sick you got to work at it. You’ve got to break all the rules. You’ve got to get hooked on something, or inhibited by it, or tied to it. Variety is the spice of life. In a great variety there is safety. So what I am trying to tell you, this is what the Bible message is about. It is, heal the sick. Heal the sick. God wants you to heal the sick. And some people think, oh that’s just to be done instantaneously. Never, never, with diet or anything else. Do you know that the health message starts in the very first chapter of Genesis? The 28th verse. The very first chapter of Genesis in the 28th verse. We are going to have a lot more to say about that as the week goes on. -

The Literary Fate of Marina Tsve Taeva, Who in My View Is One Of

A New Edition of the Poems of Marina Tsve taeva1 he literary fate of Marina Tsvetaeva, who in my view is one of the T most remarkable Russian poets of the twentieth century, took its ultimate shape sadly and instructively. The highest point of Tsve taeva’s popularity and reputation during her lifetime came approximately be- tween 1922 and 1926, i.e., during her first years in emigration. Having left Russia, Tsve taeva found the opportunity to print a whole series of collec- tions of poetry, narrative poems, poetic dramas, and fairy tales that she had written between 1916 and 1921: Mileposts 1 (Versty 1), Craft (Remes- lo), Psyche (Psikheia), Separation (Razluka), Tsar-Maiden (Tsar’-Devitsa), The End of Casanova (Konets Kazanovy), and others. These books came out in Moscow and in Berlin, and individual poems by Tsve taeva were published in both Soviet and émigré publications. As a mature poet Tsve- taeva appeared before both Soviet and émigré readership instantly at her full stature; her juvenile collections Evening Album (Vechernii al’bom) and The Magic Lantern (Volshebnyi fonar’) were by that time forgotten. Her success with readers and critics alike was huge and genuine. If one peruses émigré journals and newspapers from the beginning of the 1920s, one is easily convinced of the popularity of Marina Tsve taeva’s poetry at that period. Her writings appeared in the Russian journals of both Prague and Paris; her arrival in Paris and appearance in February 1925 before an overflowing audience for a reading of her works was a literary event. Soviet critics similarly published serious and sympathetic reviews. -

PHYSICAL HANDICAPPING Steve Thygersen December 14, 2011

PHYSICAL HANDICAPPING Steve Thygersen December 14, 2011 OVERALL APPEARANCE The ideal horse is well proportioned, alert without being fixated, has a beautiful shiny coat with dappling and there is a spring in their step and their head is high and neck bowed. It doesn’t hurt when they are playful as well – giving the groom a face full of nose or nipping at their pony and then jumping back. Horses like to play, and young horses really like to play. If you are playful, you aren’t scared of the upcoming race, in fact you are ready to roll. I see trainers all the time try to get them to stop being playful and I always think “shouldn’t this be fun for them?”. One of the most playful horses I ever saw was Majestic Prince back in the late 60s – he seemed to take great pleasure in getting Johnny Longden to bust a gasket. The second you turned your back on him he would slyly start sneaking away. He almost got away on the day of the Santa Anita Derby but Longden turned to him and bellowed “Don’t even think about it!” He stopped dead in his tracks and waited for them to come get him. He also liked to grab Longden by the back of the pants and lift his head up. The only horse I know that delighted in giving Melvins. The point is a playful horse is a happy horse and happy horses run. COAT, MANE AND TAIL The eyes may be the windows to the soul, but the coat is the mirror of their physical condition. -

Russians Abroad-Gotovo.Indd

Russians abRoad Literary and Cultural Politics of diaspora (1919-1939) The Real Twentieth Century Series Editor – Thomas Seifrid (University of Southern California) Russians abRoad Literary and Cultural Politics of diaspora (1919-1939) GReta n. sLobin edited by Katerina Clark, nancy Condee, dan slobin, and Mark slobin Boston 2013 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: The bibliographic data for this title is available from the Library of Congress. Copyright © 2013 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved ISBN 978-1-61811-214-9 (cloth) ISBN 978-1-61811-215-6 (electronic) Cover illustration by A. Remizov from "Teatr," Center for Russian Culture, Amherst College. Cover design by Ivan Grave. Published by Academic Studies Press in 2013. 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com Effective December 12th, 2017, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. The open access publication of this volume is made possible by: This open access publication is part of a project supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book initiative, which includes the open access release of several Academic Studies Press volumes. To view more titles available as free ebooks and to learn more about this project, please visit borderlinesfoundation.org/open. Published by Academic Studies Press 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com Table of Contents Foreword by Galin Tihanov ....................................... -

2008 File1lined.Vp

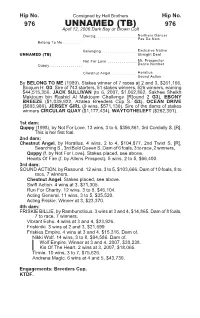

Hip No. Consigned by Hall Brothers Hip No. 976 UNNAMED (TB) 976 April 12, 2006 Dark Bay or Brown Colt Danzig .....................Northern Dancer Pas De Nom Belong To Me .......... Belonging ..................Exclusive Native UNNAMED (TB) Straight Deal Not For Love ...............Mr. Prospector Quppy................. Dance Number Chestnut Angel .............Horatius Sound Action By BELONG TO ME (1989). Stakes winner of 7 races at 2 and 3, $261,166, Boojum H. G3. Sire of 743 starters, 51 stakes winners, 526 winners, earning $44,515,356, JACK SULLIVAN (to 6, 2007, $1,062,862, Sakhee Sheikh Maktoum bin Rashid Al Maktoum Challenge [R]ound 2 G3), EBONY BREEZE ($1,039,922, Azalea Breeders Cup S. G3), OCEAN DRIVE ($803,986), JERSEY GIRL (9 wins, $571,136). Sire of the dams of stakes winners CIRCULAR QUAY ($1,177,434), WAYTOTHELEFT ($262,391). 1st dam: Quppy (1998), by Not For Love. 13 wins, 3 to 6, $356,861, 3rd Cordially S. [R]. This is her first foal. 2nd dam: Chestnut Angel, by Horatius. 4 wins, 2 to 4, $104,877, 2nd Twixt S. [R], Searching S., 3rd Bold Queen S. Dam of 6 foals, 3 to race, 2 winners, Quppy (f. by Not For Love). Stakes placed, see above. Hearts Of Fire (f. by Allens Prospect). 5 wins, 2 to 5, $66,400. 3rd dam: SOUND ACTION, by Resound. 12 wins, 3 to 5, $103,666. Dam of 10 foals, 8 to race, 7 winners, Chestnut Angel. Stakes placed, see above. Swift Action. 4 wins at 3, $71,305. Run For Charity. 12 wins, 3 to 8, $46,104. -

Saul Tchernichowsky and Vladislav Khodasevich

1 2 3 jÖrg schulte 5 saul tchernichowsky and Vladislav Khodasevich A chapter in Philological cooperation 10 When saul tchernichowsky arrived in berlin in december 1922, he was forty seven years old and at the hight of his creative strength.1 Within two years he pub- lished the Book of Idylls (sefer ha-idilyot), the Book of Sonnets (Ma½beret son- 15 etot) and the volume New Songs (shirim ½adashim). the irst to announce tch- ernichowsky’s arrival in berlin was his fellow poet iakov Kagan who wrote a long article for the russian journal Razsvet on january 14, 1923. Kagan revealed to his readers what tchernichowsky had told him about his yet unpublished works. he also reported that tchernichowsky had studied medieval hebrew medical manu- 20 scripts in the state library of st Petersburg (then Petrograd) and had been forced to leave a considerable part of his work behind when he led to odessa.2 We still do not have any trace of these materials. We know that in the company of ã. n. bialik, tchernichowsky attended the farewell concert of the russian songwriter Alexander Vertinsky at the scala theatre (in berlin) on november 7, 1923, and 3 25 was deeply impressed by the poet who sang his own verses. We also know that in the same year, he lived next door to the actress Miriam bernstein-cohen who, like himself, held a degree in medicine and translated from russian into he- brew.4 in her memoirs, Miriam bernstein-cohen notes that she introduced tch- ernichowsky to Aharon (Armand), Kaminka who had been the irst to translate 5 6 30 a part of the Iliad into hebrew in 1882.