Thesis Equestrianism: Serious Leisure And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arabian Reining Breeders Classic

WHAt’s Online: TACK TALK | HEALTH MATTERS | WHAt’s NEW | SUBSCRIBE TO QHN | SHOP LD SERIE S NCHA WOR MERCURIA/ LD CUP YOUTH WOR Cutters Take The LOOKING BACK International Youth Stage In Canada CURVE LEARNING Reining And The World Meet In Texas Business Sense Equestrian Games For Horsemen Digital Update The Complete Source for the Performance Horse Industry Week of August 18, 2014 F a m i l y Fun The Swales family wins big at the Calgary Stampede. WHAt’s INSIDE ■ Out 'N' About: West Texas Futurity ■ Equi-Stat: ICHA Futurity & Aged Event ■ FYI: Clearing Cobwebs / $3.9 9 / AUGUST 15, 2014 VOLUME 36, NUMBER 16 NEWS.COM The Professionals QUARTERHORSE ■ TAHC Welcomes Horse Team Arabian Reining formance year- lings within the Breeders Classic next few years. ext month will mark a major The ARBC also turnaround for Arabian and has developed NHalf-Arabian reining horses an annual youth and their riders, breeders and own- scholarship pro- ers. They will have an opportunity to gram. It is offer- display their talents during the debut ing $30,000 in of the Arabian Reining Breeders scholarships for Classic (ARBC), to be held during the youth at two High Roller Reining Classic (HRRC), ARBC-approved Sept. 13-20 at the South Point events – the 2014 Equestrian Center in Las Vegas. HRRC and the While it has been said that some 2015 Scottsdale trainers look down on showing Arabian an Arabian reining horse, Equi- Horse Show. Stat Elite $3 Million Rider Andrea Osteen Schatzberg Scholarship Fappani disagrees. “The truth is Arabian reiner All Maxed Out RA and Andrea Fappani determination is that a good horse is a good horse,” based on finan- Fappani said. -

Western Youth Horsemanship Schools

The Instructors For photos, updates, and more information: The University of Findlay Western Youth Horse- manship School Like us on Facebook Randy Wilson, Randy is a riding instructor at the University of Findlay’s Western Equestrian Program. He also has operated Randy Wilson Quarter Horses for the past 34 years, where he specializes in training Western Pleasure horses for Open and Non-Pro events. Randy graduated from the University of Findlay in 1983. Since then, he has earned numerous futurity and champion titles at events such as the All- American Quarter Horse Congress, the NSBA World Championship Show, the AQHA World Championship Show, and APHA World Champi- onship Show. Wilson was inducted into the NSBA Quarter Million Dollar Club in 2008 and was named Most Valuable Professional Horse- man of The Year by the Ohio Quarter Horse As- sociation in 2017. Additional Questions / Information Clark Bradley, Clark has been an instructor in the UF Western Equestrian Program for 23 years and has also helped coach the UF IHSA Western Equestrian Team. He graduated from the Ranch Contact: Carol Browne Management Program at Texas Christian Univer- WESTERN YOUTH sity and also served in the U.S. Marine Corp. 419-434-4656 HORSEMANSHIP Clark has trained horses for over 40 years. Email: [email protected] SCHOOLS A member of the NRHA and the All American Quarter Horse Congress Hall of Fame, Clark is also a two-time NRHA Futurity Champion and has won multiple championships at the Quarter The University of Findlay Advanced Horse Congress in versatility, reining, pleasure, Animal Science Center June 9-13 cutting, and roping. -

Double the Double

Digital Update Breaking News SUBSCRIBE NOW Peptoboonsmal to to Quarter Horse News Stand the 2010 Season and get the Nov. 1 issue • NRCHA Snaffle in Weatherford Bit Futurity Jackson Land and Cattle LLC • Christmas Gift Guide announced that Peptoboonsmal, • Brazos Bash one of the leading sires of perfor- mance horses, will stand the 2010 season at ESMS on the Brazos, a WEEK OF OCTOBER 12, 2009 QUARTERHORSENEWS.COM new facility in Weatherford, Texas. ESMS on the Brazos, Equine JReproduction Center & Fertility Lab, is the newest division of Equine Sports Medicine and ... Double the Read more at quarterhorsenews.com. Video See the Action Central Custom Cash Advance and Duane Latimer Watch Custom Cash Advance KIRKBRID and Duane Latimer’s Futurity Open finals winning run at the E Ariat Tulsa Reining Classic. Fun! PHO T im Blumer’s Double OG GET THE LATEST J Ranches, Maysville, RAP ONLINE NOW AT JOkla., and Moscow, HY Pa., had double the fun at The Tradition Reining Futurity, held Sept. 12 Jenna Blumer and Sweet Sugarpepto n GUNNATRASHYA / SHAWN at the Kentucky Horse Park, Lexington, Ky. FLARIDA WIN CONGRESS REINING FUTURITY Double J Ranches is home to Lenas Sugarman Sugars Lil Whiz is by West Coast Whiz Gunnatrashya (Colonels Smoking (Doc O’Lena x Sugar Gay Bar x Doc’s out of Sugarmans Belle; Sweet Sugarpepto is Gun x Natrasha x Trashadeous), rid- Sug) and Imasmartpepto (Peptoboonsmal x by Imasmartpepto out of Sweet Sugar Peppy. den by Shawn Flarida for Arcese Imasmartlittlesugar x Smart Little Lena). Both dams are by Lenas Sugarman. Both Quarter Horses, Weatherford, Texas, 3-year-olds were bred, raised and started at scored a 225.5 to win the Reining Lenas Sugarman started his career as a Futurity Open finals. -

Equine Activity Sponsor Or Professional

CHAPTER 53-10 EQUINE ACTIVITY SPONSOR OR PROFESSIONAL 53-10-01. Definitions. In this chapter, unless the context or subject matter otherwise requires: 1. "Engages in an equine activity" means a person who rides, trains, drives, or is a passenger upon an equine, whether mounted or unmounted, and does not mean a spectator in equine activity or a person who participates in the equine activity but does not ride, train, drive, or ride as a passenger upon an equine. 2. "Equine" means a horse, pony, mule, donkey, or hinny. 3. "Equine activity" means: a. An equine show, fair, competition, performance, or parade that involves any breed of equine in any equine discipline, including dressage, a hunter and jumper horse show, grand prix jumping, a three-day event, combined training, a rodeo, driving, pulling, cutting, polo, steeplechasing, endurance, trail riding, guided trail rides, pleasure trail riding, wagon and buggy rides, and western games and hunting; b. An equine training or teaching activity; c. Boarding an equine; d. Riding, inspecting, or evaluating an equine belonging to another whether or not the owner has received some monetary consideration or other thing of value for the use of the equine or is permitting a prospective purchaser of the equine to ride, inspect, or evaluate the equine; and e. A ride, trip, hunt, or other equine activity of any type however informal or impromptu that is sponsored by an equine activity sponsor. 4. "Equine activity sponsor" means an individual, group, club, partnership, corporation, or limited liability company, whether or not the sponsor is operating for profit or nonprofit, which sponsors, organizes, or provides the facility for an equine activity including a pony club, 4-H club, hunt club, riding club, school or college-sponsored class or program, therapeutic riding program, and an operator, instructor, or promoter of an equine facility including but not limited to a stable, clubhouse, pony ride string, fair, or arena at which the activity is held. -

The History of International Equestrian Sports

“... and Allah took a handful of Southerly wind... and created the horse” The history of international equestrian sports Susanna Hedenborg Department of Sport Sciences, Malmö University Published on the Internet, www.idrottsforum.org/hedenborg140613, (ISSN 1652–7224), 2014-06-13 Copyright © Susanna Hedenborg 2014. All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the author. The aim of this paper is to chart the relationship between men, women and horses with focus on equestrian sports. The degree of internationality of these sports, as well as the question of whether a sport can be seen as international if only men or women participate, are discussed. Furthermore, the diffusion of equestrian sports are presented; in short, equestrian activities spread interna- tionally in different directions up until the late 19th century. Since then Olympic Equestrian events (dressage, show jumping and eventing) have been diffused from Europe. Even though men and women are allowed to compete against each other in the equestrian events, the number of men and women varies widely, irrespective of country, and until this imbalance is redressed, equestrian sports cannot be seen as truly international. SUSANNA HEDENBORG iis professor of sport studies at Malmö University, Sweden. Her research focuses on sport history as well as on issues of gender and age. Currently she is working with the international history of equestrian sports, addressing the interchangeable influences of gender, age and nationality. -

Proceedings of the 1St International Equitation Science Symposium 2005

Proceedings of the 1st International Equitation Science Symposium 2005 Friday 26th and Saturday 27th August, 2005 Australian Equine Behaviour Centre, Melbourne, Australia. Editors: P. McGreevy, A. McLean, A. Warren-Smith, D. Goodwin, N. Waran i Organising Committee: S. Botterrill, A. McLean, A. Warren-Smith, D. Goodwin, N. Waran, P. McGreevy Contact: Australian Equine Behaviour Centre, Clonbinane, Broadford, VIC 3569, Australia. Email: [email protected] ISBN: ii Contents Page Timetable 1 Welcome 2 The evolution of schooling principles and their influence on the 4 horse’s welfare Ödberg FO Defining the terms and processes associated with equitation 10 McGreevy PD, McLean AN, Warren-Smith AK, Waran N and Goodwin D A low cost device for measuring the pressures exerted on domestic 44 horses by riders and handlers. Warren-Smith AK, Curtis RA and McGreevy PD Breed differences in equine retinae 56 Evans KE and McGreevy PD Equestrianism and horse welfare: The need for an ‘equine-centred’ 67 approach to training. Waran N The use of head lowering in horses as a method of inducing calmness. 75 Warren-Smith AK and McGreevy PD Epidemiology of horses leaving the Thoroughbred and Standardbred 84 racing industries Hayek AR, Jones B, Evans DL, Thomson PC and McGreevy PD A preliminary study on the relation between subjectively assessing 89 dressage performances and objective welfare parameters de Cartier d’Yves A and Ödberg FO Index 111 iii Timetable Friday 26th Activity Presenters August Registration: Tea/coffee on arrival at the Australian Equine -

Saddle Fit Guide

Contents Signs of Poor Saddle Fit 3 Rider Saddle Fit Checklist 4 The 9 Points of Saddle Fitting 5 Personal Saddle Fitting Evaluations 6 Saddle Fit For Women 7 When Horses Behave Badly 10 Information & Resources 12 Pan Am Team Silver Medalist Tina Irwin with Laurentio © 2016. Saddle Fitting Guide by Schleese Saddery Service Ltd. All Rights Reserved. July 2016. | 2 Protecting Horse and Rider from Long-Term Damage Signs of Poor Saddle Fit to Rider • feeling ‘pulled apart’ at the hips • back pain • neck pain • knee pain • slipped disc • urinary tract infections • pelvic discomfort • poor position • behind or in front of the motion • knees and toes out • fighting the saddle • chair seat • legs swinging • out of balance • feeling ‘jarred’ during sitting trot Signs of Poor Saddle Fit to Horse • resistance • ‘girthiness’ • lack of engagement • stumbling, tripping • rearing, bucking • tight hollow back • sore sensitive back • irregular gaits • 4 beat canter • tongue faults • poor work attitude • pinned back ears • blisters • tail swishing • swelling • stress lines • hunter’s bump • muscles atrophy • lameness If your equipment doesn’t fit, you will have huge problems from the get go. You won’t get very far with a horse that isn’t comfortable, a saddle that doesn’t fit, and as a result, a rider that is out of balance because the saddle pushes him too far forward or back. Christilot Boylen, Canadian Dressage Team Member, multi-Olympian © 2016. Signs of Poor Saddle Fit by SaddleFit4Life. All Rights Reserved. Saddle Fit Checklist for the Rider Courtesy of Saddlefit 4 Life® If the saddle doesn’t fit the rider well, the rider’s pain and discomfort will translate down to the horse and the saddle will never fit the horse correctly. -

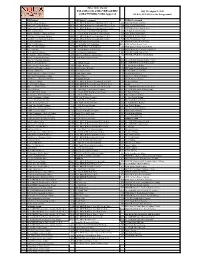

Silver State Circuit Full AQHA with AQHA VRH and RHC AQHA

Silver State Circuit Full AQHA with AQHA VRH and RHC July 29-August 1, 2021 AQHA/WSVRHA/NQHA Approved ELKO, NEVADA at the Fairgrounds THURSDAY THURSDAY continued FRIDAY continued 147 Amt Yearling Stallions 1037 ALL BREED Hunt Seat Equitation W/T 10 & U 409 YOUTH RANCH TRAIL 148 Amt Two Yr Old Stallions 1038 ALL BREED Hunt Seat Equitation W/T 19 & O 410 VRH Youth Ranch Trail 149 Amt Three Yr Old Stallions 1039 ALL BREED Hunt Seat Equitation W/T Youth 411 WSVRHA Youth Ranch Trail 150 Amt Aged Stallions 222 L1 Amt Walk Trot Hunt Seat Equitation 413 JUNIOR RANCH TRAIL 27 Amt Performance Halter Stallions 223 L1 Youth Walk Trot Hunt Seat Equitation 414 VRH Junior Ranch Trail 15 Amt Grand Champion Stallion 1042 ALL BREED Hunt Seat Equitation 19 & O 415 SENIOR RANCH TRAIL 16 Amt Reserve Champion Stallion 1043 ALL BREED Hunt Seat Equitation Youth 416 VRH Senior Ranch Trail 151 Yearling Stallions 234 RK Amt Hunt Seat Equitation 417 WSVRHA Open Ranch Trail 152 Two Yr Old Stallions 235 L1 Amt Hunt Seat Equitation 418 VRH Cowboy Ranch Trail 153 Three Yr Old Stallions 236 RK Youth Hunt Seat Equitation 419 VRH Limited Youth Ranch Trail 154 Aged Stallions 237 L1 Youth Hunt Seat Equitation 420 WSVRHA Limited Youth Ranch Trail 1031 ALL BREED Stallions 238 Amt Hunt Seat Equitation 421 VRH RK Youth Ranch Trail 28 Performance Halter Stallions 239 Amt Select Hunt Seat Equitation 422 WSVRHA Walk Trot Ranch Trail 13 Grand Champion Stallions 240 Youth Hunt Seat Equitation 14 Reserve Champion Stallions 1015 ALL BREED Western Riding 19 & O 159 Amt Yearling Geldings -

Cow Horse Classes

Continuing Education Program for AHA Licensed Officials Cow Horse Classes 12/1/19 COW HORSE CLASSES INTRODUCTION • While some AHA Judges and Stewards are familiar with cow horse classes, most do not get the chance to work them often enough to gain valuable experience. This module is an overview of the various types of cow horse classes in Arabian shows today and will you help you gain the confidence needed to work a show with cow horse classes. COW HORSE CLASSES • At Arabian shows, there are three divisions of cow horse classes: Working Cow Horse, Reined Cow Horse and Cutting. • Scoring for each division ranges from 60-80 points. COW HORSE CLASSES • In addition to the USEF Rule Book, AR Rules refer to the AHA Handbook, National Reined Cow Horse Association and the National Cutting Horse Association rules for specific sections. COW HORSE CLASSES WORKING COW HORSE • Working Cow Horse classes consist of one phase. • One cow is released into the arena and the rider has to complete a series of maneuvers, showing control of the cow. • There is no pattern. COW HORSE CLASSES WORKING COW HORSE • There is no time limit, other than the “new cow rule”. • The judge will blow a whistle to signify they have seen enough work. • Time is usually kept by the announcer. • The judge will have a scribe. COW HORSE CLASSES WORKING COW HORSE MANUEVERS The maneuvers include: • boxing (keeping the cow at one end of the arena), • turning on the fence (running the cow down the arena fence and turning him back the other way) and • circling (maneuvering the cow smoothly at least 360 degrees in each direction without using the fence). -

2013. De Lingüística, Traducción Y Lexico-Fraseología

De Lingüística, traducción y lexico-fraseología Homenaje a Juan de Dios Luque Durán Antonio Pamies Bertrán (ed.) De lingüística, traducción y lexico-fraseología Homenaje a Juan de Dios Luque Durán Granada, 2013 Colección indexada en la MLA International Bibliography desde 2005 EDITORIAL COMARE S Director de publicaciones: MIGUEL ÁNGEL DEL ARCO TORRES INTERLINGUA 111 Directores académicos de la colección: EMILO ORTEGA ARJONILLA PEDRO SAN GINÉS AGUILAR Comité Científco (Asesor): ESPERANZA ALARCÓN NAVÍO Universidad de Granada MARIA JOAO MARÇALO Universidade de Évora JESÚS BAIGORRI JALÓN Universidad de Salamanca HUGO MARQUANT *OTUJUVU-JCSF.BSJF)BQT #SVYFMMFT CHRISTIAN BALLIU ISTIEF#SVYFMMFT FRANCISCO MATTE BON LUSPIO de Roma LORENZO BLINI LUSPIO de RomA JOSÉ MANUEL MUÑOZ MUÑOZ 6OJWFSTJEBEEF$ØSEPCB ANABEL BORJA ALBÍ 6OJWFSTJUBU+BVNF*EF$BTUFMMØO FERNANDO NAVARRO DOMÍNGUEZ Universidad de Alicante NICOLÁS A. CAMPOS PLAZA Universidad de Murcia NOBEL A. PERDU HONEYMAN Universidad de Almería MIGUEL A. CANDEL MORA Universidad Politécnica de Valencia MOISÉS PONCE DE LEÓN IGLESIAS Université de Rennes ÁNGELA COLLADOS AÍS Universidad de Granada )BVUF#SFUBHOF ELENA ECHEVERRÍA PEREDA 6OJWFSTJEBEEF.ÈMBHB BERNARD THIRY *OTUJUVU-JCSF.BSJF)BQT #SVYFMMFT PILAR ELENA GARCÍA Universidad de Salamanca FERNANDO TODA IGLESIA Universidad de Salamanca FRANCISCO J. GARCÍA MARCOS Universidad de Almería ARLETTE VÉGLIA 6OJWFSTJEBE"VUØOPNBEF.BESJE CATALINA JIMÉNEZ HURTADO Universidad de Granada CHELO VARGAS SIERRA Universidad de Alicante ÓSCAR JIMÉNEZ SERRANO Universidad -

The Following Event Descriptions Are Presented for Your Edification and Clarification on What Is Being Represented and Celebrated in Bronze for Our Champions

The following event descriptions are presented for your edification and clarification on what is being represented and celebrated in bronze for our champions. RODEO: Saddle Bronc Riding Saddle Bronc has been a part of the Calgary Stampede since 1912. Style, grace and rhythm define rodeo’s “classic” event. Saddle Bronc riding is a true test of balance. It has been compared to competing on a balance beam, except the “apparatus” in rodeo is a bucking bronc. A saddle bronc rider uses a rein attached to the horse’s halter to help maintain his seat and balance. The length of rein a rider takes will vary on the bucking style of the horse he is riding – too short a rein and the cowboy can get pulled down over the horse’s head. Of a possible 100 points, half of the points are awarded to the cowboy for his ride and spurring action. The other half of the points come from how the bronc bucks and its athletic ability. The spurring motion begins with the cowboy’s feet over the points of the bronc’s shoulders and as the horse bucks, the rider draws his feet back to the “cantle’, or back of the saddle in an arc, then he snaps his feet back to the horse’s shoulders just before the animal’s front feet hit the ground again. Bareback Riding Bareback has also been a part of the Stampede since 1912. In this event, the cowboy holds onto a leather rigging with a snug custom fit handhold that is cinched with a single girth around the horse – during a particularly exciting bareback ride, a rider can feel as if he’s being pulled through a tornado. -

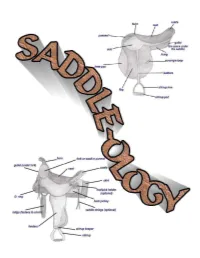

Saddleology (PDF)

This manual is intended for 4-H use and created for Maine 4-H members, leaders, extension agents and staff. COVER CREATED BY CATHY THOMAS PHOTOS OF SADDLES COURSTESY OF: www.horsesaddleshop.com & www.western-saddle-guide.com & www.libbys-tack.com & www.statelinetack.com & www.wikipedia.com & Cathy Thomas & Terry Swazey (permission given to alter photo for teaching purposes) REFERENCE LIST: Western Saddle Guide Dictionary of Equine Terms Verlane Desgrange Created by Cathy Thomas © Cathy Thomas 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction.................................................................................4 Saddle Parts - Western..................................................................5-7 Saddle Parts - English...................................................................8-9 Fitting a saddle........................................................................10-15 Fitting the rider...........................................................................15 Other considerations.....................................................................16 Saddle Types & Functions - Western...............................................17-20 Saddle Types & Functions - English.................................................21-23 Latigo Straps...............................................................................24 Latigo Knots................................................................................25 Cinch Buckle...............................................................................26 Buying the right size