Odessa Und Das Vierte Reich: Mythen Der Zeitgeschichte'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography

Bibliography Archival Insights into the Evolution of Economics (and Related Projects) Berlet, C. (2017). Hayek, Mises, and the Iron Rule of Unintended Consequences. In R. Leeson (Ed.), Hayek a Collaborative Biography Part IX: Te Divine Right of the ‘Free’ Market. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. Farrant, A., & McPhail, E. (2017). Hayek, Tatcher, and the Muddle of the Middle. In R. Leeson (Ed.), Hayek: A Collaborative Biography Part IX the Divine Right of the Market. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. Filip, B. (2018a). Hayek on Limited Democracy, Dictatorships and the ‘Free’ Market: An Interview in Argentina, 1977. In R. Leeson (Ed.), Hayek a Collaborative Biography Part XIII: ‘Fascism’ and Liberalism in the (Austrian) Classical Tradition. Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan. Filip, B. (2018b). Hayek and Popper on Piecemeal Engineering and Ordo- Liberalism. In R. Leeson (Ed.), Hayek a Collaborative Biography Part XIV: Orwell, Popper, Humboldt and Polanyi. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. Friedman, M. F. (2017 [1991]). Say ‘No’ to Intolerance. In R. Leeson & C. Palm (Eds.), Milton Friedman on Freedom. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press. © Te Editor(s) (if applicable) and Te Author(s) 2019 609 R. Leeson, Hayek: A Collaborative Biography, Archival Insights into the Evolution of Economics, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-78069-6 610 Bibliography Glasner, D. (2018). Hayek, Gold, Defation and Nihilism. In R. Leeson (Ed.), Hayek a Collaborative Biography Part XIII: ‘Fascism’ and Liberalism in the (Austrian) Classical Tradition. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. Goldschmidt, N., & Hesse, J.-O. (2013). Eucken, Hayek, and the Road to Serfdom. In R. Leeson (Ed.), Hayek: A Collaborative Biography Part I Infuences, from Mises to Bartley. -

Eichmann and the Grand Mufti

Jewish Political Studies Review Review Article 22(Spring 2010)1-2 Updated Webversion 5-2010 Nazis on the Run Tripartite Networks in Europe, the Middle East and America Gerald Steinacher, a historian from the West Austrian town of Innsbruck, is known for his solid re- search on the federal state of Tyrol under the Third Reich. His new book reconstructs how Nazis fled from Europe via Italy to South America after the end of World War II. The author also claims that his research proves that stories about a secret organization of former SS members are nothing more than a myth. According to this thesis, ODESSA, the Organisation Der Ehemaligen SS Angehörigen (Organi- zation of Former SS Members), did not exist. Before dealing with this finding in the context of the Middle East, an overview of the book is in order. Steinacher first discusses the southern escape route via Rome to Genoa and other Italian towns. He then explores the mechanism of obtaining a new identity through Red Cross papers, and details how Vatican circles provided assistance. The reader learns all about the “Rat Run” from Germany through Italy and finally to the safe haven of Argentina. Italy, Steinacher notes, was Europe’s backyard. But it was also, like Spain and Portugal, the Middle East’s front yard. Weltecho, Simon Wiesenthal 1947, 63 1946: On the hunt for Eichmann and the Grand Mufti Three major organizations helped the Nazis escape from Europe. The Catholic Church believed this ef- fort would contribute to the “re-Christianization” of Europe and feared the threat to Europe of paga- nism and communism. -

German Jewish Refugees in the United States and Relationships to Germany, 1938-1988

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO “Germany on Their Minds”? German Jewish Refugees in the United States and Relationships to Germany, 1938-1988 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Anne Clara Schenderlein Committee in charge: Professor Frank Biess, Co-Chair Professor Deborah Hertz, Co-Chair Professor Luis Alvarez Professor Hasia Diner Professor Amelia Glaser Professor Patrick H. Patterson 2014 Copyright Anne Clara Schenderlein, 2014 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Anne Clara Schenderlein is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically. _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair _____________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2014 iii Dedication To my Mother and the Memory of my Father iv Table of Contents Signature Page ..................................................................................................................iii Dedication ..........................................................................................................................iv Table of Contents ...............................................................................................................v -

Identificación De Criminales De Guerra· Llegados a La Argentina Según Fuentes Locales

Ciclos, Año X, Vol. X, N° 19, 1er. semestre de 2000 Documentos Identificación de criminales de guerra· llegados a la Argentina según fuentes locales Carlota Jackisch* y Daniel Mastromauro** El presente trabajo documenta él ingreso al país de criminales de guerra y responsables de crímenes contra la humanidad, pertenecientes al nazis mo y a regímenes aliados al Tercer Reich, o bajo su ocupación. Se trata de una muestra de 65 casos de un total de 180 individuos detectados, alema nes y de otras nacionalidades, tanto sospechados como encausados, pro cesados o convictos de tales crímenes. Parte de un universo que segura mente excede los 180, la información ofrecidaproviene de la consulta, por vez primera, de fuentes documentales del Ministerio. del Interior (sección documentación personal de la Policía Federal y área certificaciones de la Dirección General de Migraciones.) El relevamiento de tales fuentes se hi zo sobre la base de sus identidades reales o del conocimiento a partir de fuentes extranjeras de las identidades ficticias con que ingresaron al país. Se ofrece a contunuación una sinopsis biográfica de los criminales de gue rra nazis y colaboracionistas que llegaron a la Argentina al finalizar el con flicto bélico. Nazis ALVEN8LEBEN, Ludolf Hermann Dirigente de las SS (Schutzstajjel-Escuadras de Protección Nazis) en Rusia. Su detención fue ordenada por un juzgado de Munich, República Federal de Alema nia, acusado de la matanza de polacos según datos de la Zentraller Stelleder Lan desjustízverwaltung (en adelante Ludwigsburgo), el organismo alemán que .con- * Fundación Konrad Adenauer. ** Universidad de Buenos Aires. 218 Carlota Jackisch y Daniel Mastromauro centra toda la Información que la justicia alemana posee sobre, acusados, de haber cometido delitos relacionados con el accionar delrégimen nacionalsocialista. -

Verschucr, Helmut Von. 13, 77-78 Verschtter, Omar Freiherr Von, 11

3 6 4 Index Verschucr, Helmut von. 13, 77-78 Wiesenthal, Simon (cont.): Verschtter, Omar Freiherr von, 11-13, 214, 219. 245-247, 248, 251-252, 14, 17-18, 33, 34, 39, 41, 59, 60, 69, 256, 294, 298, 299, 304. 306, 317- 77-78 318, 320n, 321 Vessey Camben, Juan, 171 Wiesenthal Center; 84, 208, 209, 306, "Vieland," 68-70, 74, 75, 76, 78. 80 308, 319 Viera de C23(1), Maria, 320, 321 Wirths, Eduard, 24, 25-26, 78 Vilka Carranza, Juan, 247-248 Wladeger, Anton and F.deltraud, 162n Wellman, Henrique, 301 Wagner, Gustav, 315 World in Action (11r), special program on Wagner, Richard. 13 Mengele, 202-203 War Crimes Branch, Civil Affairs Division, World Health Organization, 122 Washington, 82, 85 World Jewish Congress, 126-127 Ware, John, xviii, 202-203, 296 "Worthless life" concept, 1ln, 45, 80 Warren Commission. 302-303 Washington Times, 308 "Xavier," 88 Welt, Die. 317 West German Prosecutor's Of6ce, 24 Ynsfran, Edgar. 129, 149, 159, 180, 194, White, Peter, 296, 297-298 195-196, 197, 201 Wiedwald, Erich Karl, 216-217 Wiesenthal, Simon, 23n, 136n, 161, 169- Zamir, Zvi, 246 170, 193, 199, 206-210, 212, 213- Zinn, August, 136 ISBN 0-07-050598-5 >$18.95 (continued from front flap) if[11cow STORY► • Proof that Mengele was captured and held for two months under his own name by the U.S. Army. Gerald L. Posner and • Substantial evidence that West Ger- John Ware many and Israel could have captured Mengele on two separate occasions and failed to do so. This is the definitive life story of Dr. -

TV TV Sender 20 ARD RTL Comedy Central RTL2 DAS VIERTE SAT.1

TV Anz. Sender TV Sender 20 ARD (national) RTL Comedy Central (01/2009) RTL2 DAS VIERTE (1/2006) SAT.1 DMAX (1/2007) Sixx (01/2012) EuroSport (nur Motive) Sport 1 (ehemals DSF) Kabel Eins Super RTL N24 Tele 5 (1/2007) Nickelodeon (ehemals Nick) VIVA N-TV VOX Pro Sieben ZDF Gesamtergebnis TV Sender 20 Radio Anz. Sender Radio Sender 60 104,6 RTL MDR 1 Sachsen-Anhalt 94,3 rs2 MDR1 Thüringen Antenne Bayern NDR 2 Antenne Brandenburg Oldie 95 Antenne Mecklenburg-Vorpommern Planet Radio Antenne Thüringen R.SH Radio Schleswig-Holstein Bayern 1 Radio Berlin 88,8 Bayern 2 Radio Brocken Bayern 3 Radio Eins Bayern 4 Radio FFN Bayern 5 Radio Hamburg Bayern Funkpaket Radio Nora BB Radio Radio NRW Berliner Rundfunk 91!4 Radio PSR big FM Hot Music Radio Radio SAW Bremen 1 Radio-Kombi Baden Württemberg Bremen 4 RPR 1. Delta Radio Spreeradio Eins Live SR 1 Fritz SR 3 Hit-Radio Antenne Star FM Hit-Radio FFH SWR 1 Baden-Württemberg (01/2011) HITRADIO RTL Sachsen SWR 1 Rheinland-Pfalz HR 1 SWR 3 HR 3 SWR 4 Baden-Württemberg (01/2011) HR 4 SWR 4 Rheinland-Pfalz Inforadio WDR 2 Jump WDR 4 KISS FM YOU FM Landeswelle Thüringen MDR 1 Sachsen Gesamtergebnis Radio Sender 60 Plakat Anz. Städte Städte 9 Berlin Frankfurt Hamburg Hannover Karlsruhe Köln Leipzig München Halle Gesamtergebnis Städte 9 Seite 1 von 19 Presse ZIS Anz. Titel ZIS Anz. Titel Tageszeitungen (TZ) 150 Tageszeitungen (TZ) 150 Regionalzeitung 113 Regionalzeitung 113 BaWü 16 Hamburg 3 Aalener Nachrichten/Schwäbische Zeitung 100111 Hamburger Abendblatt 101659 Badische Neueste Nachrichten 100121 Hamburger -

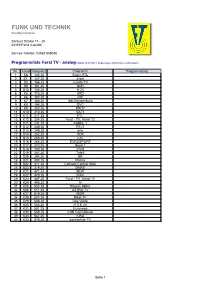

FUNK UND TECHNIK Breitbandnetze

FUNK UND TECHNIK Breitbandnetze Sorauer Straße 17 - 25 03149 Forst (Lausitz) Service-Telefon: 03562 959030 Programmliste Forst TV - analog (Stand: 26.07.2013, Änderungen und Irrtümer vorbehalten) Nr. Kanal Frequenz Programm Programmplatz 1 S6 140,25 Super-RTL 2 S7 147,25 3-sat 3 S8 154,25 Juwelo TV 4 S9 161,25 NDR 5 S10 168,25 N-24 6 K5 175,25 ARD 7 K6 182,25 ZDF 8 K7 189,25 rbb Brandenburg 9 K8 196,25 QVC 10 K9 203,25 PRO7 11 K10 210,25 SAT1 12 K11 217,25 RTL 13 K12 224,25 Forst - TV, Kanal 12 14 S11 231,25 KABEL 1 15 S12 238,25 RTL2 16 S13 245,25 arte 17 S14 252,25 VOX 18 S15 259,25 n-tv 19 S16 266,25 EUROSPORT 20 S17 273,25 Sport 1 21 S18 280,25 VIVA 22 S19 287,25 Tele5 23 S20 294,25 BR 24 S21 303,25 Phönix 25 S22 311,25 Comedy Central /Nick 26 S23 319,25 DMAX 27 K21 471,25 MDR 28 K22 479,25 SIXX 29 K23 487,25 Forst - TV, Kanal 12 30 K24 495,25 hr 31 K25 503,25 Bayern Alpha 32 K26 511,25 ASTRO TV 33 K27 519,25 WDR 34 K28 527,25 Bibel TV 35 K29 535,25 Das Vierte 36 K30 543,25 H.S.E.24 37 K31 551,25 Euronews 38 K32 559,25 CNN International 39 K33 567,25 KIKA 40 K34 575,25 sonnenklar TV Seite 1 Programmliste Forst TV - digital (Stand: 26.07.2013, Änderungen vorbehalten) Nr. -

Favoritenliste 1 Tvprogrammname Provider Satellit Frequenz Polarisation SR 1 !Funspice Globecast 538020 6875 2

Favoritenliste 1 TVProgrammname Provider Satellit Frequenz Polarisation SR 1 !FunSpice GlobeCast 538020 6875 2 . BetaDigital 314010 6875 3 . SKY 418010 6875 4 . SKY 362010 6875 5 . SKY 362010 6875 6 . SKY 394010 6875 7 .Viva L'Italia Channel GlobeCast 538020 6875 8 1-2-3.tv BetaDigital 314010 6875 9 1+1 International GlobeCast 538020 6875 10 2BE 113010 6875 11 3sat HD ZDFvision 514020 6875 12 3sat ZDFvision 338030 6875 13 13th Street SKY 426020 6875 14 13th Street HD SKY 121010 6875 15 Ahl Al Bhait GlobeCast 538020 6875 16 Animax 113010 6875 17 ANIXE HD BetaDigital 498030 6875 18 ANIXE SD BetaDigital 314010 6875 19 ARD-TEST-1 ARD 386020 6875 20 Ariana TV GlobeCast 538020 6875 21 arte ARD 306020 6875 22 arte HD ARD 490030 6875 23 ASTRA Portal BetaDigital 498030 6875 24 AstroTV BetaDigital 378020 6875 25 ATV ATV+ 458030 6875 26 Bayerisches FS Nord ARD 442020 6875 27 Bayerisches FS Süd ARD 442020 6875 28 Beate-Uhse.TV SKY 394010 6875 29 Blue Movie SKY 418010 6875 30 Blue Movie 1 426020 6875 31 Blue Movie 2 426020 6875 32 Blue Movie 3 426020 6875 33 BR Nord HD ARD 506030 6875 34 BR Süd HD ARD 506030 6875 35 BR-alpha ARD 370030 6875 36 Canvas 113010 6875 37 Classica SKY 394010 6875 38 Club-RTL 113010 6875 39 collection BetaDigital 314010 6875 40 Das Erste ARD 442020 6875 41 Das Erste HD ARD 490030 6875 42 DAS VIERTE BetaDigital 314010 6875 43 DAYSTAR TV GlobeCast 538020 6875 44 Discovery 113010 6875 45 Discovery Channel SKY 418010 6875 46 Discovery HD SKY 362010 6875 47 Disney Channel SKY 394010 6875 48 Disney Channel HD SKY 113010 6875 49 -

H. Con. Res. 248

III 109TH CONGRESS 1ST SESSION H. CON. RES. 248 IN THE SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES OCTOBER 17, 2005 Received and referred to the Committee on Foreign Relations CONCURRENT RESOLUTION Honoring the life and work of Simon Wiesenthal and re- affirming the commitment of Congress to the fight against anti-Semitism and intolerance in all forms, in all forums, and in all nations. Whereas Simon Wiesenthal, who was known as the ‘‘con- science of the Holocaust’’, was born on December 31, 1908, in Buczacz, Austria-Hungary, and died in Vienna, Austria, on September 20, 2005, and he dedicated the last 60 years of his life to the pursuit of justice for the victims of the Holocaust; 2 Whereas, during World War II, Simon Wiesenthal worked with the Polish underground and was interned in 12 dif- ferent concentration camps until his liberation by the United States Army in 1945 from the Mauthausen camp; Whereas, after the war, Simon Wiesenthal worked for the War Crimes Section of the United States Army gathering documentation to be used in prosecuting the Nuremberg trials; Whereas Simon Wiesenthal’s investigative work and expan- sive research was instrumental in the capture and convic- tion of more than 1,000 Nazi war criminals, including Adolf Eichmann, the architect of the Nazi plan to annihi- late European Jewry, and Karl Silberbauer, the Gestapo officer responsible for the arrest and deportation of Anne Frank; Whereas numerous honors and awards were bestowed upon Simon Wiesenthal, including the Congressional Gold Medal, honorary British Knighthood, the -

Österreich Und Die Flucht Von NS-Tätern Nach Übersee Gerald Steinacher University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, Department of History History, Department of 2016 Österreich und die Flucht von NS-Tätern nach Übersee Gerald Steinacher University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historyfacpub Part of the European History Commons, and the Military History Commons Steinacher, Gerald, "Österreich und die Flucht von NS-Tätern nach Übersee" (2016). Faculty Publications, Department of History. 195. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historyfacpub/195 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, Department of History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. JAHRBUCH MAUTHAUSEN KZ-GEDENKSTÄTTE MAUTHAUSEN | MAUTHAUSEN MEMORIAL NS-Täterinnen und -Täter 2016 in der Nachkriegszeit FORSCHUNG | DOKUMENTATION | INFORMATION KZ-GEDENKSTÄTTE MAUTHAUSEN MAUTHAUSEN MEMORIAL 2016 NS-Täterinnen und -Täter in der Nachkriegszeit KZ-Gedenkstätte Mauthausen | Mauthausen Memorial 2016 Impressum HERAUSGEBERIN: KZ-Gedenkstätte Mauthausen/Mauthausen Memorial Bundesanstalt öffentlichen Rechts MITHERAUSGEBER: Andreas Kranebitter REDAKTION: Gregor Holzinger, Andreas Kranebitter GESAMTLEITUNG: LEKTORAT: Barbara Glück Martin Wedl WISSENSCHAFTLICHE BETREUUNG: LAYOUT/GRAFIK: Bertrand Perz Grafik-Design Eva Schwingenschlögl -

Operation Greif and the Trial of the “Most Dangerous Man in Europe.”

Operation Greif and the Trial of the “Most Dangerous Man in Europe.” A disheveled George S. Patton reported to Dwight Eisenhower with unsettling news from the front. “Ike, I’ve never seen such a goddamn foul-up! The Krauts are infiltrating behind our lines, raising hell, cutting wires and turning around road signs!”1 Such was the characteristic response in the aftermath of Operation Greif, orchestrated by Germany’s top commando, Otto Skorzeny. Through his actions during the Ardennes Offensive of 1944, and his acquittal while on trial, Skorzeny effectively utilized disinformation and covert operations to both earn his credibility and infamous reputation. Born in Vienna in 1908, Skorzeny led a mundane life during the years of the First World War. Despite his inability to concentrate on his studies, he managed to graduate in 1931 from the Technischen Hochschule in Wien with an engineering degree.2 His participation in the Schlagende Verbindungen (dueling societies) during his academic career gave Skorzeny the reputation of being a fierce fighter and resulted in his characteristic scars that covered both sides of his face. With the unification of Austria into Germany in 1938, Skorzeny had his first contact with the Nazi party. While visiting Vienna, he came upon Austrian President Miklas in the midst of an attempt on his life by Nazi roughnecks. Skorzeny, always a man of action, blocked the way of the would-be assassins and ended the confrontation. Word spread across the Germany of the bold Austrian who had saved the President’s life on a whim. 1 Glenn B Infield, Skorzeny (New York: St. -

The Kpd and the Nsdap: a Sttjdy of the Relationship Between Political Extremes in Weimar Germany, 1923-1933 by Davis William

THE KPD AND THE NSDAP: A STTJDY OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN POLITICAL EXTREMES IN WEIMAR GERMANY, 1923-1933 BY DAVIS WILLIAM DAYCOCK A thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. The London School of Economics and Political Science, University of London 1980 1 ABSTRACT The German Communist Party's response to the rise of the Nazis was conditioned by its complicated political environment which included the influence of Soviet foreign policy requirements, the party's Marxist-Leninist outlook, its organizational structure and the democratic society of Weimar. Relying on the Communist press and theoretical journals, documentary collections drawn from several German archives, as well as interview material, and Nazi, Communist opposition and Social Democratic sources, this study traces the development of the KPD's tactical orientation towards the Nazis for the period 1923-1933. In so doing it complements the existing literature both by its extension of the chronological scope of enquiry and by its attention to the tactical requirements of the relationship as viewed from the perspective of the KPD. It concludes that for the whole of the period, KPD tactics were ambiguous and reflected the tensions between the various competing factors which shaped the party's policies. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE abbreviations 4 INTRODUCTION 7 CHAPTER I THE CONSTRAINTS ON CONFLICT 24 CHAPTER II 1923: THE FORMATIVE YEAR 67 CHAPTER III VARIATIONS ON THE SCHLAGETER THEME: THE CONTINUITIES IN COMMUNIST POLICY 1924-1928 124 CHAPTER IV COMMUNIST TACTICS AND THE NAZI ADVANCE, 1928-1932: THE RESPONSE TO NEW THREATS 166 CHAPTER V COMMUNIST TACTICS, 1928-1932: THE RESPONSE TO NEW OPPORTUNITIES 223 CHAPTER VI FLUCTUATIONS IN COMMUNIST TACTICS DURING 1932: DOUBTS IN THE ELEVENTH HOUR 273 CONCLUSIONS 307 APPENDIX I VOTING ALIGNMENTS IN THE REICHSTAG 1924-1932 333 APPENDIX II INTERVIEWS 335 BIBLIOGRAPHY 341 4 ABBREVIATIONS 1.