Young Composers in Irish Traditional Music C. 2004 – 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1St Annual Dreams Come True Feis Hosted by Central Florida Irish Dance Sunday August 8Th, 2021

1st Annual Dreams Come True Feis Hosted by Central Florida Irish Dance Sunday August 8th, 2021 Musician – Sean Warren, Florida. Adjudicator’s – Maura McGowan ADCRG, Belfast Arlene McLaughlin Allen ADCRG - Scotland Hosted by - Sarah Costello TCRG and Central Florida Irish Dance Embassy Suites Orlando - Lake Buena Vista South $119.00 plus tax Call - 407-597-4000 Registered with An Chomhdhail Na Muinteoiri Le Rinci Gaelacha Cuideachta Faoi Theorainn Rathaiochta (An Chomhdhail) www.irishdancingorg.com Charity Treble Reel for Orange County Animal Services A progressive animal-welfare focused organization that enforces the Orange County Code to protect both citizens and animals. Entry Fees: Pre Bun Grad A, Bun Grad A, B, C, $10.00 per competition Pre-Open & Open Solo Rounds $10.00 per competition Traditional Set & Treble Reel Specials $15.00 per competition Cup Award Solo Dances $15.00 per competition Open Championships $55.00 (2 solos are included in your entry) Championship change fee - $10 Facility Fee $30 per family Feisweb Fee $6 Open Platform Fee $20 Late Fee $30 The maximum fee per family is $225 plus facility fee and any applicable late, change or other fees. There will be no refund of any entry fees for any reason. Submit all entries online at https://FeisWeb.com Competitors Cards are available on FeisWeb. All registrations must be paid via PayPal Competitors are highly encouraged to print their own number prior to attending to avoid congestion at the registration table due to COVID. For those who cannot, competitor cards may be picked up at the venue. For questions contact us at our email: [email protected] or Sarah Costello TCRG on 321-200-3598 Special Needs: 1 step, any dance. -

Another One Hundred Tunes” Published October 25, 2013

O’Flaherty Irish Music Retreat “Another One Hundred Tunes” Published October 25, 2013 We decided to issue a third tunebook in celebration of the tenth year of the O’Flaherty Irish Music Retreat. It is hard to believe that a decade has passed since we held our first event at the Springhill Retreat Center in Richardson, Texas back in October of 2004. None of us who organized that first event had any indication that it would grow as it has. What started as a small local music camp has given rise to a well-respected international camp attracting participants from near and far. We have been successful over the years because of two primary factors – good teachers and good learners. Fortunately, we have never had a shortage of either so we have not only survived, but have expanded greatly in both scope and size since our founding. There is one other factor of our success that is important to remember – the music itself. Traditional Irish music is unlike any music I’ve known. On one hand, I have seldom encountered music more difficult to master. Playing “authentically” is the goal but that goal can take years if not a lifetime of listening, practicing and playing. On the other hand, the music by its nature is so accessible that it permits players to engage in it at any level of ability. It is not uncommon for experienced players to encourage novices and help establish a connection with this remarkable music tradition. That connection is the essence of what we try to do at our retreat – pass on the music as musicians have done in Ireland for centuries. -

2020 Syllabus

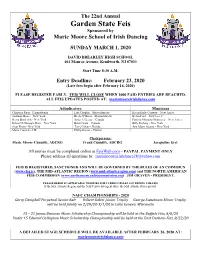

The 22nd Annual Garden State Feis Sponsored by Marie Moore School of Irish Dancing SUNDAY MARCH 1, 2020 DAVID BREARLEY HIGH SCHOOL 401 Monroe Avenue, Kenilworth, NJ 07033 Start Time 8:30 A.M. Entry Deadline: February 23, 2020 (Late fees begin after February 16, 2020) PLEASE REGISTER EARLY. FEIS WILL CLOSE WHEN 1000 PAID ENTRIES ARE REACHED. ALL FEIS UPDATES POSTED AT: mariemooreirishdance.com Adjudicators Musicians Christina Ryan - Pennsylvania Lisa Chaplin – Massachusetts Karen Early-Conway – New Jersey Siobhan Moore - New York Breda O’Brien – Massachusetts Kevin Ford – New Jersey Kerry Broderick - New York Jackie O’Leary – Canada Patricia Moriarty-Morrissey – New Jersey Eileen McDonagh-Morr – New York Brian Grant – Canada Billy Furlong - New York Sean Flynn - New York Terry Gillan – Florida Ann Marie Acosta – New York Marie Connell – UK Philip Owens – Florida Chairpersons: Marie Moore-Cunniffe, ADCRG Frank Cunniffe, ADCRG Jacqueline Erel All entries must be completed online at FeisWeb.com – PAYPAL PAYMENT ONLY Please address all questions to: [email protected] FEIS IS REGISTERED, SANCTIONED AND WILL BE GOVERNED BY THE RULES OF AN COIMISIUN (www.clrg.ie), THE MID-ATLANTIC REGION (www.mid-atlanticregion.com) and THE NORTH AMERICAN FEIS COMMISSION (www.northamericanfeiscommission.org) JIM GRAVEN - PRESIDENT. PLEASE REFER TO APPLICABLE WEBSITES FOR CURRENT RULES GOVERNING THE FEIS If the Mid-Atlantic Region and the NAFC have divergent rules, the Mid-Atlantic Rules prevail. NAFC CHAMPIONSHIPS - 2020 Gerry Campbell Perpetual -

“Whiskey in the Jar”: History and Transformation of a Classic Irish Song Masters Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of

“Whiskey in the Jar”: History and Transformation of a Classic Irish Song Masters Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Dana DeVlieger, B.A., M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2016 Thesis Committee: Graeme M. Boone, Advisor Johanna Devaney Anna Gawboy Copyright by Dana Lauren DeVlieger 2016 Abstract “Whiskey in the Jar” is a traditional Irish song that is performed by musicians from many different musical genres. However, because there are influential recordings of the song performed in different styles, from folk to punk to metal, one begins to wonder what the role of the song’s Irish heritage is and whether or not it retains a sense of Irish identity in different iterations. The current project examines a corpus of 398 recordings of “Whiskey in the Jar” by artists from all over the world. By analyzing acoustic markers of Irishness, for example an Irish accent, as well as markers of other musical traditions, this study aims explores the different ways that the song has been performed and discusses the possible presence of an “Irish feel” on recordings that do not sound overtly Irish. ii Dedication Dedicated to my grandfather, Edward Blake, for instilling in our family a love of Irish music and a pride in our heritage iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Graeme Boone, for showing great and enthusiasm for this project and for offering advice and support throughout the process. I would also like to thank Johanna Devaney and Anna Gawboy for their valuable insight and ideas for future directions and ways to improve. -

The Roots Report: Beat the Heat with Cool Shows

The Roots Report: Beat the Heat with Cool Shows Okee dokee folks … It’s summer. I would be remiss if I didn’t reiterate my feelings about it. I hate summer. I am sorry. I know many of you folks like summer. I am not a fan of the heat and humidity. Fortunately, we are more than halfway through. Music makes the summer easier to deal with – for me anyway. There are still a lot of summer shows to catch while the weather is warm, though sometimes “warm” can be a bit of an understatement. Onward. The Downtown Sundown Series The Downtown Sundown Series has been steadily gaining a solid audience, mostly by word of mouth. Every show brings more folks who are amazed by the talent of the performers and the beauty of Roger Williams National Memorial. Now in its third year, this music series brings free music into downtown Providence two Saturdays per month. Already this season, performers such as WS Monroe, Billy Mitchell, Malyssa Bellarosa, Kala Farnham, Mark Cutler, Heather Rose, Tracie Potochnik, Bob Kendall, Jesse Liam and Jack Gauthier, and others have graced the park stage with their wonderful music. The middle lawn at the Memorial is the perfect spot for a sundown show. The music starts at 7 pm and continues until 9:30 pm, and four performers are featured at each show. The audience members sit back in lawn chairs, lie on blankets or directly on the grass and enjoy some of the best singer- songwriters from the area. Picnickers are welcomed and encouraged. -

Tradition and Innovation in Irish Instrumental Folk Music

TRADITION AND INNOVATION IN IRISH INSTRUMENTAL FOLK MUSIC by ANDREW NEIL fflLLHOUSE B.Mus., The University of British Columbia, 1990 B.Ed., The University of British Columbia, 2002 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Music) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA August 2005 © Andrew Neil Hillhouse, 2005 11 ABSTRACT In the late twentieth century, many new melodies were composed in the genre of traditional Irish instrumental music. In the oral tradition of this music, these new tunes go through a selection process, ultimately decided on by a large, transnational, and loosely connected community of musicians, before entering the common-practice repertoire. This thesis examines a representative group of tunes that are being accepted into the common- practice repertoire, and through analysis of motivic structure, harmony, mode and other elements, identifies the shifting boundaries of traditional music. Through an identification of these boundaries, observations can be made on the changing tastes of the people playing Irish music today. Chapter One both establishes the historical and contemporary context for the study of Irish traditional music, and reviews literature on the melodic analysis of Irish traditional music, particularly regarding the concept of "tune-families". Chapter Two offers an analysis of traditional tunes in the common-practice repertoire, in order to establish an analytical means for identifying traditional tune structure. Chapter Three is an analysis of five tunes that have entered the common-practice repertoire since 1980. This analysis utilizes the techniques introduced in Chapter Two, and discusses the idea of the melodic "hook", the memorable element that is necessary for a tune to become popular. -

Dissertation Final Submission Andy Hillhouse

TOURING AS SOCIAL PRACTICE: TRANSNATIONAL FESTIVALS, PERSONALIZED NETWORKS, AND NEW FOLK MUSIC SENSIBILITIES by Andrew Neil Hillhouse A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto © Copyright by Andrew Neil Hillhouse (2013) ABSTRACT Touring as Social Practice: Transnational Festivals, Personalized Networks, and New Folk Music Sensibilities Andrew Neil Hillhouse Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto 2013 The aim of this dissertation is to contribute to an understanding of the changing relationship between collectivist ideals and individualism within dispersed, transnational, and heterogeneous cultural spaces. I focus on musicians working in professional folk music, a field that has strong, historic associations with collectivism. This field consists of folk festivals, music camps, and other venues at which musicians from a range of countries, affiliated with broad labels such as ‘Celtic,’ ‘Nordic,’ ‘bluegrass,’ or ‘fiddle music,’ interact. Various collaborative connections emerge from such encounters, creating socio-musical networks that cross boundaries of genre, region, and nation. These interactions create a social space that has received little attention in ethnomusicology. While there is an emerging body of literature devoted to specific folk festivals in the context of globalization, few studies have examined the relationship between the transnational character of this circuit and the changing sensibilities, music, and social networks of particular musicians who make a living on it. To this end, I examine the career trajectories of three interrelated musicians who have worked in folk music: the late Canadian fiddler Oliver Schroer (1956-2008), the ii Irish flute player Nuala Kennedy, and the Italian organetto player Filippo Gambetta. -

Road to the Isles the Traditional Music, Dance, & Folksongs of Ireland and Scotland. the Musicians

Road to the Isles PRESS RELEASE Road to the Isles The Traditional Music, Dance, & Folksongs of Ireland and Scotland. Featuring: George Balderose: Highland Pipes & Smallpipes; Oliver Browne: Irish Fiddle; Melinda Crawford: Scottish Fiddle; Brittany Maniet: Scottish Dance; Caroline McCarthy: Irish Dance; Richard Hughes: Great Flute, Guitar, vocals. Drawing from a wealth of experience and study, Road to the Isles performs the instrumental music, dance, and folksong traditions of Ireland and Scotland. Comprising five talented performers representing years of experience in their respective fields, Road to the Isles will take you on a journey to the lochs and glens of the Celtic lands of old. Their performances include the sword dance, highland fling, sean triubhas, Irish reel and jig, slip jig, and hornpipe, complemented by songs, stories, and instrumental solos, duets, and trios. The ensemble portrays a unique view of the similarities and differences between the music and dance traditions of these fascinating and ancient cultures. About their CD release, The Way Home, it has been said: "Excellent traditional Irish and Scottish music" (Celtic Heritage, Halifax, Nova Scotia); "The musicianship reflects the high-level training, attainments, and year's of experience of the ensemble's members" (Piping Today, Glasgow, Scotland); "A top quality introduction to genuine Scottish and Irish traditional music…" (Common Stock. Journal of the Lowland and Borders Pipers Society, Edinburgh, Scotland) Dancers Brittany Maniet and Caroline McCarthy represent two different traditions of dancing, and each has successfully competed at Irish Feis and Highland Games throughout the Northeast US. Their performances will highlight and contrast the dance styles of their respective traditions. -

5EHC 2020 Awards Recipients

July 16, 2020 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Rosanne Royer, Awards Chair (503) 871-1023 cell [email protected] Ethnic Heritage Council announces Recipients of the 2020 Annual EHC Awards to Ethnic Community Leaders and Artists The Ethnic Heritage Council (EHC) is proud to announce this year’s award recipients, to be honored at EHC’s 40th Anniversary celebration. The special event is rescheduled to Spring 2021, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, date to be determined. The awards program with annual meeting is EHC’s major annual event. The award recipients represent extraordinary achievements and contributions to the region’s cultural and community life. We invite you to read their biographies below. The 2020 EHC Award Recipients Rita Zawaideh Bart Brashers Spirit of Liberty Award Aspasia Phoutrides Pulakis Memorial Award Randal Bays Emiko Nakamura Bud Bard Co-Recipient Co-Recipient EHC Leadership Gordon Ekvall Tracie Gordon Ekvall Tracie & Service Award Memorial Award Memorial Award Rita Zawaideh 2020 “Spirit of Liberty” Award Eestablished in 1986 and given to a naturalized citizen who has made a significant contribution to his or her ethnic community and ethnic heritage, as well as to the community at large. For decades Rita Zawaideh has been an advocate and change-maker on behalf of Middle Eastern and North African communities in the United States and around the world. She is a “one-person community information center for the Arab community,” according to the thousands who have benefited from her activism and philanthropy. “The door to Rita’s Fremont office is always open,” says Huda Giddens of Seattle’s Palestinian community, adding that Rita's strength is her ability to see a need and answer it. -

A Primer on Reels, Jigs, and Strathspeys by Ward Fleri, San Diego Branch 11 February 2021 for the New York Branch (Updated 25 March 2021) Thoughts on Music and Dance

A Primer on Reels, Jigs, and Strathspeys By Ward Fleri, San Diego Branch 11 February 2021 For the New York Branch (Updated 25 March 2021) Thoughts on Music and Dance • “The music is the stimulus of the dance and dance should be the physical expression of the music” Jean Milligan • “Dancing is music made visible” George Balanchine Time Signatures • Common time signatures: • 4/4 – Reels, Strathspeys • 2/4 – Reels • 2/2 – Reels • 6/8 – Jigs • 9/8 – Slip Jigs • 3/4 – Waltzes The terms duple, triple, and quadruple refer to the number of beats per measure/bar Reel Jig Waltz Slip Jig Reel, Strathspey Note Notation Musical Overview • Jigs • Reels • Double Jigs • High Energy (aka Running, • Pipe Jigs Driving, Killer) Reels • Single Jigs/Two-Steps • Hornpipes • Slip Jigs • Song Tunes • Strathspeys • Marches, Polkas and Others • Strong/traditional Strathspeys • Slow Airs and Songs • Schottisches, Highland Strathspeys Jigs • Double Jig – most common Laird of Milton’s Daughter • Laird of Milton’s Daughter • River Cree • The Wild Geese • The Express • Roaring Jelly • 6/8 Pipe March (64 bars) • Blue Bonnets - AABBCCDD • Duke of Atholl’s Reel Single Jigs The Frisky • Ian Powrie’s Farewell to Archterarder • Rothesay Rant • White Heather Jig • The Nurseryman • The Frisky Slip Jigs • Slip Jig • Strip the Willow Strathspeys – Scotch Snap Traditional (Strong) Strathspeys • Gang the Same Gate Gang the Same Gate • Up in the Air • Braes of Tulliemet • Invercauld’s Reel • Sugar Candie • John McAlpin Strathspeys – Slow Airs, Songs • Slow Airs The Lea Rig • Miss Gibson’s S’pey • Autumn in Appin • Songs • Lea Rig • Sean Truibhas Willichan Schottisches, Highland Strathspeys • Glasgow Highlands • Foursome Reel Reels – High Energy (Running, Driving, Killer) • Sleepy Maggie • Lady Susan Stewart’s Reel • Pinewoods Reel • General Stuart’s Reel • The Highlandman Kissed His Mother • Montgomeries’ Rant • De’il Amang the Tailors Reels - Hornpipes West’s Horn. -

2.5 Graded Requirements: Irish Traditional Music

2.5 Graded requirements: Irish Traditional Music See page 43 for the graded requirements for bodhrán examinations. Step - Irish Traditional Music The candidate will be expected to perform four tunes. The tunes should be simple in type (for example, easy marches, airs, polkas, etc). No ornamentation or embellishment will be expected but credit will be given for accuracy, fluency, phrasing and style. 25 marks per piece. See page 24 for suggested repertoire for this grade. Grade 1 - Irish Traditional Music See page 24 for suggested repertoire for this grade. Component 1: Performance 60 marks The candidate will be expected to perform three tunes of different types. Ornamentation is not required but the performance should be fluent, well phrased and in style. Component 2: Repertoire 20 marks Three tunes of different types should be prepared and one will be heard at the examiner’s discretion. Ornamentation is not required but the performance should be fluent, well phrased and in style. Component 3: Supplementary Tests 20 marks x To beat time (clap or foot tap) in a polka, double jig or reel performed by the examiner. x To identify tune types (air, polka or double jig) performed by the examiner. x To identify instruments (tin whistle, flute, fiddle, accordion) in audio extracts played by the examiner. x To describe the candidate’s own instrument in detail and name a prominent player of the instrument. Grade 2 - Irish Traditional Music See page 24 for suggested repertoire for this grade. Component 1: Performance 60 marks The candidate will be expected to perform three tunes of different types, at least one of which must be a hornpipe, jig or reel. -

Folk Music 1 Folk Music

Folk music 1 Folk music Folk music Béla Bartók recording Slovak peasant singers in 1908 Traditions List of folk music traditions Musicians List of folk musicians Instruments Folk instruments Folk music is an English term encompassing both traditional folk music and contemporary folk music. The term originated in the 19th century. Traditional folk music has been defined in several ways: as music transmitted by mouth, as music of the lower classes, and as music with unknown composers. It has been contrasted with commercial and classical styles. This music is also referred to as traditional music and, in US, as "roots music". Starting in the mid-20th century a new form of popular folk music evolved from traditional folk music. This process and period is called the (second) folk revival and reached a zenith in the 1960s. The most common name for this new form of music is also "folk music", but is often called "contemporary folk music" or "folk revival music" to make the distinction.[1] This type of folk music also includes fusion genres such as folk rock, electric folk, and others. While contemporary folk music is a genre generally distinct from traditional folk music, it often shares the same English name, performers and venues as traditional folk music; even individual songs may be a blend of the two. Traditional folk music Definitions A consistent definition of traditional folk music is elusive. The terms folk music, folk song, and folk dance are comparatively recent expressions. They are extensions of the term folk lore, which was coined