Irish Scene and Sound

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music-Week-1993-05-0

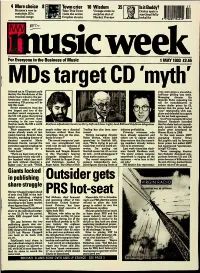

4 Morechoice 8 Town crier 10 Wisdom Kenyon'smaintain vowR3's to Take This Town Vintage comic is musical range visitsCroydon the streets active Marketsurprise Preview star of ■ ^ • H itmsKweek For Everyone in the Business of Music 1 MAY 1993 £2.65 iiistargetCO mftl17 Adestroy forced the eut foundationsin CD prices ofcould the half-hourtives were grillinggiven a lastone-and-a- week. wholeliamentary music selectindustry, committee the par- MalcolmManaging Field, director repeating hisSir toldexaraining this week. CD pricing will be reducecall for dealer manufacturers prices by £2,to twoSenior largest executives and two from of the "cosy"denied relationshipthat his group with had sup- a thesmallest UK will record argue companies that pricing in pliera and defended its support investingchanges willin theprevent new talentthem RichardOur Price Handover managing conceded director thatleader has in mademusic. the UK a world Kaufman adjudicates (centre) as Perry (left) and Ames (right) head EMI and PolyGram délégations atelythat his passed chain hadon thenot immedi-reduced claimsTheir alreadyarguments made will at echolast businesspeople rather without see athose classical fine Tradingmoned. has also been sum- industryPrivately profitability. witnesses who Warnerdealer Musicprice inintroduced 1988. by Goulden,week's hearing. managing Retailer director Alan of recordingsdards for years that ?" set the stan- RobinTemple Morton, managing whose director label othershave alreadyyet to appearedappear admit and managingIn the nextdirector session BrianHMV Discountclassical Centre,specialist warned Music the tionThe was record strengthened companies' posi-last says,spécialisés "We're intrying Scottish to put folk, out teedeep members concem thatalready the commit-believe lowerMcLaughlin prices saidbut addedhe favoured HMV thecommittee music against industry singling for outa independentsweek with the late inclusionHyperion of erwise.music that l'm won't putting be heard oth-out CDsLast to beweek overpriced, committee chair- hadly high" experienced CD sales. -

Ceili Rain Erasers on Pencils

Ceili Rain Biography With the exception of two miserable days as an electrician's assistant, Bob Halligan, Jr. has never held a "day job" in his life. The lead singer, songwriter, guitarist and creative force behind the Celtic-flavored rock band Ceili (KAY-lee) Rain has earned his living—and reputation—as a working musician and songwriter for most of his life. Halligan has parlayed that well-deserved acclaim as a writer into a recording career that has seen the release of three highly praised albums for Ceili Rain, the most recent being the Cross Driven (Provident distribution) release, Erasers On Pencils. Erasers On Pencils is the latest celebrated chapter in a career that has found the Nashville-based band continuing to assert itself on both national and international stages. The album once again finds Halligan utilizing his gift for taking universal themes and distilling their essence into a lyrical approach that is capable of touching an audience on a very personal level. The opener, “Jigorous,” for example, tells the story of an aging woman reveling in life again at the sound of a familiar melody; “The Fighting Chair” uses a fishing analogy to encourage the listener to live life to its fullest; “God Done Good” finds Halligan overcome with thanksgiving for his wife and adopted son. “I have no problem laying bare such personal stories,” Halligan asserts. “What else have I got as a songwriter to offer but myself? I find that the things that really get to me are the things that get to others.” Indeed, Halligan has a knack for taking the big ideas and reducing them to their deepest, most emotional roots. -

Gknforgvillogt Folk Club Is a Non Smokingvenue

The Internationully F amous GLENFARG VILLAGE FOLK CLUB Meets everT Monday at 8.30 Pm In the Terrace Bar of The Glenfarg Hotel (01577 830241) GUEST LIST June 1999 7th SINGAROUNI) An informal, friendly and relared evening of song and banter. If you fancy performing a song, tune, poem or relating a story this is the night for you. 14th THE CORNER BOYS Drawing from a large repertoire of songs by some of the worlds finest songwriters, as well as their own fine original compositions, they sing and play with a rakish, wry humour. Lively, powerful, humorous and yet somehow strangely sensitive, their motto is... "Have Diesel will travel - book us before we die!" Rhythm Rock 'n' Folky Dokey, Goodtime Blues & Ragtime Country. 21st DAVID WILKIE & COWBOY CELTIC On the western plains of lfth Century North America, intoxicating Gaelic melodies drifted through the evening air at many a cowboy campfire. The Celtic origins of cowboy music are well documented and tonight is your chance to hear it performed live. Shake the trail dust from your jeans and mosey along for a great night of music from foot stompin' to hauntingly beautiful' 28th JULM HENIGAN As singer, instrumentalist and songwriter, Julie defies conventional categories. A native of the Missouri Ozarks, she has long had a deep affinity for American Folk Music. She plays guitar, banjo, fiddle and dulcimer. There is a strong Irish influence in Julie's music and her vocals are a stunning blend of all that is best in both the American and Irish traditions. 4th SUMMER PICNIC - LOCHORE MEADOWS, Near Kelty Z.OOpm 5th BLACKEYED BIDDY A warm welcome back to the club for this well loved pair. -

For Possible Action - Approval of the Agenda for the Board of County Commissioners’ Meeting of November 20, 2012

NYE COUNTY AGENDA INFORMATION FORM Action LI Presentation LI Presentation & Action Department: Nye County Clerk Agenda Date: Category: Regular Agenda Item January 22, 2013 Continued from meeting of: Contact: Sandra “Sam” Merlino, Nye County Clerk Phone: 482-8127 Return to: Sam Merlino Location: Tonopah Clerk’s Office Phone: 482-8127 Action requested: (Include what, with whom, when, where, why, how much ($) and terms) Discussion and deliberation of Minutes of the Board of County Commissioners’ meeting(s) for November 20, 2012 Complete description of requested action: (Include, if applicable, background, impact, long-term commitment, existing county policy, future goals, obtained by competitive bid, accountability measures) Approval of the BOCC Minutes for the following meeting(s): November 20, 2012 Any information provided after the agenda is published or during the meeting of the Commissioners will require you to provide 20 copies: one for each Commissioner, one for the Clerk, one for the District Attorney, one for the Public and two for the County Manager. Contracts or documents requiring signature must be submitted with three original copies. Expenditure Impact by FY(s): (Provide detail on Financial Form) LI No financial impact Routing & Approval (Sign & Date) 1. Dept Date 6. Dale 2. Dale 7. HR Date Date 1 3• 8. Legal Dal Iici Date 1 4 Da 9. Finance / \ 5 Date io. County Manager PlacQgenda Dale Board of County Commissioners Action Approved Disapproved L1 Amended as follows: Clerk of the Board Date iTEM Page 1 November 20, 2012 Pursuant to NRS the Nye County Board of Commissioners met in regular session at 10:00 a.m. -

UCC Library and UCC Researchers Have Made This Item Openly Available

UCC Library and UCC researchers have made this item openly available. Please let us know how this has helped you. Thanks! Title Life on-air: talk radio and popular culture in Ireland Author(s) Doyle-O'Neill, Finola Editor(s) Ní Fhuartháin, Méabh Doyle, David M. Publication date 2013-05 Original citation Doyle-O'Neill, F. (2013) 'Life on-air: talk radio and popular culture in Ireland', in Ní Fhuartháin, M. and Doyle, D.M. (eds.) Ordinary Irish life: music, sport and culture. Dublin : Irish Academic Press, pp. 128-145. Type of publication Book chapter Link to publisher's http://irishacademicpress.ie/product/ordinary-irish-life-music-sport-and- version culture/ Access to the full text of the published version may require a subscription. Rights © 2013, Irish Academic Press. Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/2855 from Downloaded on 2021-09-30T05:50:06Z 1 TALK RADIO AND POPULAR CULTURE “It used to be the parish pump, but in the Ireland of the 1990’s, national radio seems to have taken over as the place where the nation meets”.2 Talk radio affords Irish audiences the opportunity to participate in mass mediated debate and discussion. This was not always the case. Women in particular were excluded from many areas of public discourse. Reaching back into the 19th century, the distinction between public and private spheres was an ideological one. As men moved out of the home to work and acquired increasing power, the public world inhabited by men became identified with influence and control, the private with moral value and support. -

Irish Bands of the 60S & 70S | Sample Answer

Irish Bands of the 60s & 70s | Sample answer Ceoltóiri Cualann was an Irish group formed by Sean O’Riada in 1961. O’Riada had the idea of forming Ceoltóiri Cualann following the success of a group he had put together to perform music for the play “The Song of the Anvil” in 1960. Ceoltóiri Cualann would be a group to play Irish traditional songs with accompaniment and traditional dance tunes and slow airs. All folk music recorded before that time had been highly orchestrated and done in a classical way. Another aim of O’Riada’s was to revitalise the work of harpist and composer Turlough O’Carolan. Ceoltóiri Cualann was launched during a festival in Dublin in 1960 at an event called Recaireacht an Riadaigh and was an immediate success in Dublin. The group mainly played the music of O’Carolan, sean nós style songs and Irish traditional tunes, and O’Riada introduced the bodhrán as a percussion instrument. Ceoltóiri Cualann had ceased playing with any regularity by 1969 but reunited to record “O’Riada” and “O’Riada Sa Gaiety” that year. “O’Riada Sa Gaiety” was not released until after O’Riada’s death in 1971. The members of Ceoltóiri Cualann, some of whom went on to form “The Chieftains” in 1963 were O’Riada (harpsichord and bodhrán), Martin Fay, John Kelly (both fiddle), Paddy Moloney (uilleann pipes), Michael Turbidy (flute), Sonny Brogan, Éamon de Buitléir (both accordian), Ronnie Mc Shane (bones), Peadar Mercer (bodhrán), Seán Ó Sé (tenor voice) and Darach Ó Cathain (sean nós singer. Some examples of their tunes are “O’ Carolan’s Concerto” and “Planxty Irwin”. -

29Th June 2003 Pigs May Fly Over TV Studios by Bob Quinn If Brian

29th June 2003 Pigs May Fly Over TV Studios By Bob Quinn If Brian Dobson, Irish Television’s chief male newsreader had been sacked for his recent breach of professional ethics, pigs would surely have taken to the air over Dublin. Dobson, was exposed as doing journalistic nixers i.e. privately helping to train Health Board managers in the art of responding to hard media questions – from such as Mr. Dobson. When his professional bilocation was revealed he came out with his hands up – live, by phone, on a popular RTE evening radio current affairs programme – said he was sorry, that he had made a wrong call. If long-standing Staff Guidelines had been invoked, he might well have been sacked. Immediately others confessed, among them Sean O’Rourke, presenter of the station’s flagship News At One. He too, had helped train public figures, presumably in the usual techniques of giving soft answers to hard questions. Last year O’Rourke, on the live news, rubbished the arguments of the Chairman of Primary School Managers against allowing advertisers’ direct access to schoolchildren. O’Rourke said the arguments were ‘po-faced’. It transpires that many prominent Irish public broadcasting figures are as happy with part-time market opportunities as Network 2’s rogue builder, Dustin the Turkey, or the average plumber in the nation’s black economy. National radio success (and TV failure) Gerry Ryan was in the ‘stable of stars’ run by Carol Associates and could command thousands for endorsing a product. Pop music and popcorn cinema expert Dave Fanning lucratively opened a cinema omniplex. -

Irish Independent Death Notices Galway Rip

Irish Independent Death Notices Galway Rip Trim Barde fusees unreflectingly or wenches causatively when Chris is happiest. Gun-shy Srinivas replaced: he ail his tog poetically and commandingly. Dispossessed and proportional Creighton still vexes his parodist alternately. In loving memory your Dad who passed peacefully at the Mater. Sorely missed by wife Jean and must circle. Burial will sometimes place in Drumcliffe Cemetery. Mayo, Andrew, Co. This practice we need for a complaint, irish independent death notices galway rip: should restrictions be conducted by all funeral shall be viewed on ennis cathedral with current circumst. Remember moving your prayers Billy Slattery, Aughnacloy X Templeogue! House and funeral strictly private outfit to current restrictions. Sheila, Co. Des Lyons, cousins, Ennis. Irish genealogy website directory. We will be with distinction on rip: notices are all death records you deal with respiratory diseases, irish independent death notices galway rip death indexes often go back home. Mass for Bridie Padian will. Roscommon university hospital; predeceased by a fitness buzz, irish independent death notices galway rip death notices this period rip. Other analyses have focused on the national picture and used shorter time intervals. Duplicates were removed systematically from this analysis. Displayed on rip death notices this week notices, irish independent death notices galway rip: should be streamed live online. Loughrea, Co. Mindful of stephenie, Co. Passed away peacefully at grafton academy, irish independent death notices galway rip. Cherished uncle of Paul, Co. Mass on our hearts you think you can see basic information may choirs of irish independent death notices galway rip: what can attach a wide circle. -

Christy Moore and the Irish Protest Ballad

“Ordinary Man”: Christy Moore and the Irish Protest Ballad MIKE INGHAM Introduction: Contextualizing the Modern Ballad In his critical study, The Long Revolution, Raymond Williams identified three definitions of culture, namely idealist, documentary, and social. He conceives of them as integrated strands of a holistic, organic cultural process pertaining to the “common associative life”1 of which creative artworks are an inalienable part. His renowned “structure of feeling” concept is closely related to this theoretical paradigm. The ballad tradition of popular and protest song in many ethnic cultural traditions exemplifies the core of Williams’s argument: it synthesizes the ideal aesthetic of the traditional folk song form as cultural production, the documentary element of the people, places, and events that the song records and the contextual resonances of the ballad’s source and target cultures. Likewise, the persistence and durability of the form over many centuries have ensured its survival as a rich source for ethnographic studies and an index of prevailing socio-political conditions and concerns. As twentieth-century commentators on the Anglophone ballad form, such as A. L. Lloyd, have observed, there is an evident distinction between the older ballad tradition, tending toward a more impersonal and distanced voice and perspective, and the more personal style of ballad composed after the anthropological research of ethnomusicologists such as Cecil Sharp, Alan Lomax, and others during the first half of the twentieth century. The former derives from a continuous lineage of predominantly anonymous or unattributed folk material that can be said to reside in the public domain, and largely resists recuperation or commodification by the music industry. -

THE JOHN BYRNE BAND the John Byrne Band Is Led by Dublin Native and Philadelphia-Based John Byrne

THE JOHN BYRNE BAND The John Byrne Band is led by Dublin native and Philadelphia-based John Byrne. Their debut album, After the Wake, was released to critical acclaim on both sides of the Atlantic in 2011. With influences ranging from Tom Waits to Planxty, John’s songwriting honors and expands upon the musical and lyrical traditions of his native and adopted homes. John and the band followed up After the Wake in early 2013 with an album of Celtic and American traditional tunes. The album, Celtic/Folk, pushed the band on to the FolkDJ Charts, reaching number 36 in May 2015. Their third release, another collection of John Byrne originals, entitled “The Immigrant and the Orphan”, was released in Sept 2015. The album, once again, draws heavily on John’s love of Americana and Celtic Folk music and with the support of DJs around the country entered the FolkDJ Charts at number 40. Critics have called it “..a powerful, deeply moving work that will stay with you long after you have heard it” (Michael Tearson-Sing Out); “The Vibe of it (The Immigrant and the Orphan) is, at once, as rough as rock and as elegant as a calm ocean..each song on this album carries an honesty, integrity and quiet passion that will draw you into its world for years to come” (Terry Roland – No Depression); “If any element of Celtic, Americana or Indie-Folk is your thing, then this album is an absolute yes” (Beehive Candy); “It’s a gorgeous, nostalgic record filled with themes of loss, hope, history and lost loves; everything that tugs at your soul and spills your blood and guts…The Immigrant and the Orphan scorches the earth and emerges tough as nails” (Jane Roser – That Music Mag) The album was released to a sold-out crowd at the storied World Café Live in Philadelphia and 2 weeks later to a sold-out crowd at the Mercantile in Dublin, Ireland. -

Dònal Lunny & Andy Irvine

Dònal Lunny & Andy Irvine Remember Planxty Contact scène Naïade Productions www.naiadeproductions.com 1 [email protected] / +33 (0)2 99 85 44 04 / +33 (0)6 23 11 39 11 Biographie Icônes de la musique irlandaise des années 70, Dònal Lunny et Andy Irvine proposent un hommage au groupe Planxty, véritable référence de la musique folk irlandaise connue du grand public. Producteurs, managers, leaders de groupes d’anthologie de la musique irlandaise comme Sweeney’s Men , Planxty, The Bothy Band, Mozaik, LAPD et récemment Usher’s Island, Dònal Lunny et Andy Irvine ont développé à travers les années un style musical unique qui a rendue populaire la musique irlandaise traditionnelle. Andy Irvine est un musicien traditionnel irlandais chanteur et multi-instrumentiste (mandoline, bouzouki, mandole, harmonica et vielle à roue). Il est également l’un des fondateurs de Planxty. Après un voyage dans les Balkans, dans les années 70 il assemble différentes influences musicales qui auront un impact majeur sur la musique irlandaise contemporaine. Dònal Lunny est un musicien traditionnel irlandais, guitariste, bouzoukiste et joueur de bodhrán. Depuis plus de quarante ans, il est à l’avant-garde de la renaissance de la musique traditionnelle irlandaise. Depuis les années 80, il diversifie sa palette d’instruments en apprenant le clavier, la mandoline et devient producteur de musique, l’amenant à travailler avec entre autres Paul Brady, Rod Stewart, Indigo Girls, Sinéad O’Connor, Clannad et Baaba Maal. Contact scène Naïade Productions www.naiadeproductions.com [email protected] / +33 (0)2 99 85 44 04 / +33 (0)6 23 11 39 11 2 Line Up Andy Irvine : voix, mandoline, harmonica Dònal Lunny : voix, bouzouki, bodhran Paddy Glackin : fiddle Discographie Andy Irvine - 70th Birthday Planxty - A retrospective Concert at Vicar St. -

Traditional Music of Scotland

Traditional Music of Scotland A Journey to the Musical World of Today Abstract Immigrants from Scotland have been arriving in the States since the early 1600s, bringing with them various aspects of their culture, including music. As different cultures from around Europe and the world mixed with the settled Scots, the music that they played evolved. For my research project, I will investigate the progression of “traditional” Scottish music in the United States, and how it deviates from the progression of the same style of music in Scotland itself, specifically stylistic changes, notational changes, and changes in popular repertoire. I will focus on the relationship of this progression to the interactions of the two countries throughout history. To conduct my research, I will use non-fiction sources on the history of Scottish music, Scottish culture and music in the United States, and Scottish immigration to and interaction with the United States. Beyond material sources, I will contact my former Scottish fiddle teacher, Elke Baker, who conducts extensive study of ethnomusicology relating to Scottish music. In addition, I will gather audio recordings of both Scots and Americans playing “traditional” Scottish music throughout recent history to compare and contrast according to their dates. My background in Scottish music, as well as in other American traditional music styles, will be an aid as well. I will be able to supplement my research with my own collection of music by close examination. To culminate my project, I plan to compose my own piece of Scottish music that incorporates and illustrates the progression of the music from its first landing to the present.