Free PDF Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zuzana Licko’Dur

Slovak dilini konuşup geleneklerini servet kazanmak için kestirme sürdürürken, okulda ikinci bir dili bir yol olacağını düşünmüşlerdi. ve yeni âdetleri öğreniyordum. Başlangıçta amaç sadece Hollandalı Bu benim farklılıkların farkına sanatçılara odaklanmaktı, ama varmamı sağladı ve bana bir sonraları içeriği yurt dışında yabancının bakış açısını verdi. Aynı çalışanları kapsar hale gelince ismi, zamanda muhtemelen her şeyi uygun biçimde, Emigre oldu. Uzun sorgulama eğilimimi geliştirdi ve ön lafın kısası, Rudy’nin arkadaşları yargıları sorgulamayı öğretti, bunlar derginin umdukları gibi kârlı da beni tasarım mesleğine çeken olmayacağını anlayınca dergiyi bize şeyler oldu. bırakıp gittiler. O sıralar ben zaten Mac ile yarattığım bitmap fontları doğmuş ama Kaliforniya Dijital yazıtipi tasarımıyla dergide kullanıyordum. Fontların dolaylarında yetişmişlerdi ilgilenmeye başlayan ilk grafik 1985’te Emigre’yi çıkartmaya tasarımcılardan ve Mac kullanan başladığımızda Mac’te sayfa ve bu yüzden girişimlerine ilk yazıtipi tasarımcılarından düzeni programları yoktu. arkasındaki Emigre (Göçmen) Grafik birisiniz. Bu nasıl oldu? PostScript ve lazer yazıcılar bile adını koydular. Aslında Resim yapmayı, Legolarla oynamayı henüz yoktu. Yazıtiplerini nokta yüzler gurbetçiler için mizahi ve matematiği seven bir çocuktum. vuruşlu ImageWriter yazıcılarda bir sanat dergisi olarak Bu yüzden mimar olmak istediğimi düşündüm ve UC Berkeley’de MRS EAVES OT Zuzana başlamış olan Emigre Çevre Tasarımı Bölümüne girdim. Dergisi zaman içinde Okula başladığımda, fotoğrafçılık, tipografi için son derece tipo ve tipografi gibi yan derslerle Licko etkin bir vitrin haline daha fazla ilgili olduğumu fark ettim. Bölüm Görsel Çalışmalar MyFonts, Creative Characters, gelmiş ve yazıtiplerinin programını durdurmuştu, ancak sayı 105, Haziran 2016 tartışıldığı avangard birçok mimarlık öğrencisinin Çeviri: Ayşe Dağıstanlı bir foruma dönüşmüştür. ufkunu genişleteceği düşünüldüğü Yaratıcı yeniden için bu dersler iptal edilmemişti. -

Indesign CC 2015 and Earlier

Adobe InDesign Help Legal notices Legal notices For legal notices, see http://help.adobe.com/en_US/legalnotices/index.html. Last updated 11/4/2019 iii Contents Chapter 1: Introduction to InDesign What's new in InDesign . .1 InDesign manual (PDF) . .7 InDesign system requirements . .7 What's New in InDesign . 10 Chapter 2: Workspace and workflow GPU Performance . 18 Properties panel . 20 Import PDF comments . 24 Sync Settings using Adobe Creative Cloud . 27 Default keyboard shortcuts . 31 Set preferences . 45 Create new documents | InDesign CC 2015 and earlier . 47 Touch workspace . 50 Convert QuarkXPress and PageMaker documents . 53 Work with files and templates . 57 Understand a basic managed-file workflow . 63 Toolbox . 69 Share content . 75 Customize menus and keyboard shortcuts . 81 Recovery and undo . 84 PageMaker menu commands . 85 Assignment packages . 91 Adjust your workflow . 94 Work with managed files . 97 View the workspace . 102 Save documents . 106 Chapter 3: Layout and design Create a table of contents . 112 Layout adjustment . 118 Create book files . 121 Add basic page numbering . 127 Generate QR codes . 128 Create text and text frames . 131 About pages and spreads . 137 Create new documents (Chinese, Japanese, and Korean only) . 140 Create an index . 144 Create documents . 156 Text variables . 159 Create type on a path . .. -

Methods for a Critical Graphic Design Practice

Title Design as criticism: methods for a critical graphic design p r a c tic e Type The sis URL https://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/id/eprint/12027/ Dat e 2 0 1 7 Citation Laranjo, Francisco Miguel (2017) Design as criticism: methods for a critical graphic design practice. PhD thesis, University of the Arts London. Cr e a to rs Laranjo, Francisco Miguel Usage Guidelines Please refer to usage guidelines at http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected] . License: Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Unless otherwise stated, copyright owned by the author Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of the Arts London – London College of Communication February 2017 First submission: October 2015 2 Abstract This practice-led research is the result of an interest in graphic design as a specific critical activity. Existing in the context of the 2008 financial and subsequent political crisis, both this thesis and my work are situated in an expanded field of graphic design. This research examines the emergence of the terms critical design and critical practice, and aims to develop methods that use criticism during the design process from a practitioner’s perspective. Central aims of this research are to address a gap in design discourse in relation to this terminology and impact designers operating under the banner of such terms, as well as challenging practitioners to develop a more critical design practice. The central argument of this thesis is that in order to develop a critical practice, a designer must approach design as criticism. -

Miramo®: Reference Guide (9.2)

Miramo® Automated Publishing Reference Guide VERSION 9.2 Copyright © 2000 - 2012 Datazone Ltd. All rights reserved. Miramo® and mmChart are trademarks of Datazone Ltd. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Readers of this documentation should note that its contents are intended for guidance only, and do not con- stitute formal offers or undertakings. ‘License Agreement’ This software, called Miramo, is licensed for use by the user subject to the terms of a License Agreement between the user and Datazone Ltd. Use of this software outside the terms of this license agreement is strictly prohibited. Unless agreed otherwise, this License Agreement grants a non-exclusive, non-transfer- able license to use the software programs and related documentation in this package (collectively referred to as Miramo) on licensed computers only. Any attempted sublicense, assignment, rental, sale or other transfer of the software or the rights or obligations of the License Agreement without prior written consent of Datazone shall be void. In the case of a Miramo Development License, it shall be used to develop appli- cations only and no attempt shall be made to remove the associated watermark included in output docu- ments by any automated method. The documentation accompanying this software must not be copied or re-distributed to any third-party in either printed, photocopied, scanned or electronic form. The software and documentation are copyrighted. Unless otherwise agreed in writing, copies of the soft- ware may be made only for backup and archival purposes. Unauthorized copying, reverse engineering, decompiling, disassembling, and creating derivative works based on the software are prohibited. -

Emigre No.40

Fall Information is in a way the opposite 1996 of garbage, although in our contemporary Guest Editor: THE INFO Andrew Blauvelt PERPLEX commercialized world they may at times Designer: Rudy VanderLans Copy Editor: appear identical. As a rule, information is Alice Polesky Emigre Fonts: something to preserve, garbage is Zuzana Licko Sales, distribution, and administration: Tim Starback something to be destroyed. However, both Sales John Todd and Darren Cruickshank can be looked on as a kind of waste product, a physical burden, and for contemporary society both are among the most pressing 1 Emigre no.40 This issue of Emigre problems today. was typeset in Base-9 and Base-12, designed – B i l l V i o l a by Zuzana Licko. Postmaster: Emigre (ISSN 1045-3717) is published quarterly for $28 per year by Emigre, Inc. 4475 D Street, Sacramento, CA 95819, U.S.A. Second class postage paid at Sacramento, CA. Postmaster please send address changes to: Emigre 4475 D Street, Sacramento, CA 95819, U.S.A. Copyright: © 1996 Emigre, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without written permission from the contributors or Quotes on inside front and back covers by Bill Viola. Emigre, Inc. Emigre is From HISTORY, 10 YEARS, AND THE DAYDREAM, in Reasons for knocking at an Empty House . Cambridge, MA a registered trademark of and London: MIT Press, 1995 Emigre Graphics. Phone: 916.451.4344 / Fax: 916.451.4351 Email (Editorial): [email protected] / Email (Subscriptions, etc.): sales @emigre.com 1 27 1 We write not to be understood 2 28 2 but to understand. -

A Guide to Quarkcopydesk 8.5 CONTENTS

A Guide to QuarkCopyDesk 8.5 CONTENTS Contents About this guide...............................................................................9 What we're assuming about you............................................................................9 Where to go for help..............................................................................................9 Conventions..........................................................................................................10 Technology note...................................................................................................10 The user interface...........................................................................11 Menus...................................................................................................................11 QuarkCopyDesk menu (Mac OS only)...........................................................................11 File menu.......................................................................................................................12 Edit menu......................................................................................................................12 Style menu.....................................................................................................................13 Component menu.........................................................................................................15 View menu.....................................................................................................................15 -

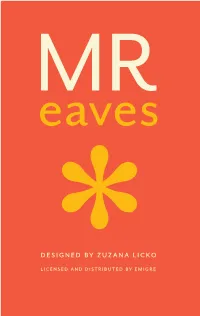

Designed by Zuzana Licko Licensed and Distributed by Emigre * Mr Eaves Type Specimen Mr Eaves Type Specimen

mr eaves type specimen 1 MReaves DesigneD by ZuZana Licko LicenseD anD DistributeD by emigre *www.emigre.com mr eaves type specimen mr eaves type specimen 2 Mr Eaves Design Notes 3 Mr Eaves is the often requested sans-serif companion to Mrs Eaves, one of Emigre’s classic typeface designs. Created by Zuzana Licko, this latest addition to the Emigre Type Library is based on the proportions of the original Mrs Eaves. aa gg tt Mr Eaves Sans and Mr Eaves Modern counterparts. A matching Modern family provides a less humanistic look, with simpler and more geometric-looking shapes, most noticeably in the squared-off aOriginal Mrs Eavesa Sans in black.d Mr Eaves Sans companiond font in white.ee terminals and symmetric lower case counters. This family has moved furthest from its roots, yet still contains some of Mrs Eaves’ DNA. Licko took some liberty with the design of Mr Eaves. One of the main concerns was to avoid creating a typeface that looked like it simply had its serifs cut off. And while it matches Mrs Eaves in weight, color, and armature, Mr Eaves stands as its own typeface with many unique charac- teristics. mMr Eaves Sans and Mrm Eaves Modern counterparts. ww The Modern Italic is free of tails, and overall the Modern exhibits more repetition of forms, projecting a cleaner look. This provides stronger differentiation from the serif version whenever a more contrasting look is f f tt cc desired. Deviations from the Mrs Eaves model are evident in the overall decrease of contrast, as well as in details such as the flag and tail of the f and j, and the finial of the t, which were shortened to maintain a cleaner, sans serif look. -

Ambition/Fear by Zuzana Licko and Rudy Vanderlans Visions of Bold

Ambition/Fear ously hinged between disciplines will find that digital technology By ZuZana Licko and Rudy VandeRLans allows them that crossover necessary for their personal expression. One such new area is that of digital type design. Custom typefaces can now be produced letter, by letter, as called for in day-by-day ap - plications. This increases the potential for more personalized type - Visions of bold-italic-outline-shadow Helvetica “Mac” tricks have faces as it becomes economically feasible to create letter forms for sent many graphic designers running back to their T-squares and specific uses. rubber cement. Knowing how and when to use computers is difficult, since we have only begun to witness their capabilities. Some design - By making publishing and dissemination of information faster and ers have found computers a creative salvation from the boredom of less expensive, computer technology has made it feasible to reach a familiar methodologies, while others have utilized this new technol - smaller audience more effectively. It is no longer necessary to market ogy to expedite traditional production processes. For this eleventh for the lowest common denominator. There is already a growth in issue of Emigre we interviewed fifteen graphic designers from around the birthrate of small circulation magazines and journals. Although the world, and talked about how they work their way through the this increases diversity and subsequently the chances of tailoring sometimes frustrating task of integrating this new technology into the product to the consumer, we can only hope that such abundance their daily practices. will not obliterate our choices by overwhelming us with options. -

Stage 1.X — Meta-Design with Machine Learning Is Coming, and That’S a Good Thing

Dialectic Volume II, Issue II: Theoretical Speculation Stage 1.X — Meta-Design with Machine Learning is Coming, and That’s a Good Thing Steven SkaggS¹ 1. University of Louisville, Department of Fine Arts, Hite Art Institute, Louisville, ky, uSa SuggeSted citation: Skaggs, Steven. “Stage 1.X—Meta-design with Machine Learning is Coming and That’s a Good Thing.” Dialectic, 2.2 (2019): pgs. 49-68. Published by the AIGA Design Educators Community (DEC) and Michigan Publishing. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/dialectic.14932326.0002.204. Abstract The capabilities of digital technology to reproduce likenesses of existing people and places and to create fictional terraformed landscapes are well known. The increasing encroachment of bots into all areas of life has caused some to wonder if a designer bot is plausible. In my recent book Fire- Signs, ¹ I note that the acute cultural, stylistic, and semantic articulations made possible by current semiotic theory may enable digital resources to work within territories that were once considered the exclusive creative domain of the graphic designer. Such metadesign assistance may be resist ed by some who fear that it will altogether replace the need for the designer. In this article, I first suggest how metadesign might enter the design process, and then explore its use to affect layout and composition. I argue that, at least within that restricted domain, it promises greater creative benefits than liabilities to human graphic designers. 1 Skaggs, S. FireSigns: A Semiotic Theory for Graphic Design. Cambridge, mA, USA: mIt Press, 2017. Copyright © 2019, Dialectic and the AIGA Design Educators Community (DEC). -

Type & Typography

Type & Typography by Walton Mendelson 2017 One-Off Press Copyright © 2009-2017 Walton Mendelson All rights reserved. [email protected] All images in this book are copyrighted by their respective authors. PhotoShop, Illustrator, and Acrobat are registered trademarks of Adobe. CreateSpace is a registered trademark of Amazon. All trademarks, these and any others mentioned in the text are the property of their respective owners. This book and One- Off Press are independent of any product, vendor, company, or person mentioned in this book. No product, company, or person mentioned or quoted in this book has in any way, either explicitly or implicitly endorsed, authorized or sponsored this book. The opinions expressed are the author’s. Type & Typography Type is the lifeblood of books. While there is no reason that you can’t format your book without any knowledge of type, typography—the art, craft, and technique of composing and printing with type—lets you transform your manuscript into a professional looking book. As with writing, every book has its own issues that you have to discover as you design and format it. These pages cannot answer every question, but they can show you how to assess the problems and understand the tools you have to get things right. “Typography is what language looks like,” Ellen Lupton. Homage to Hermann Zapf 3 4 Type and Typography Type styles and Letter Spacing: The parts of a glyph have names, the most important distinctions are between serif/sans serif, and roman/italic. Normal letter spacing is subtly adjusted to avoid typographical problems, such as widows and rivers; open, touching, or expanded are most often used in display matter. -

Inside Emigre 1984 - 2005

Deeply involved Inside Emigre 1984 - 2005 They came to the profession of graphic design not simply to assimilate but to question and also to transform it. I believe Content in me Million ideas participants Exploration 12 16 20 Rules to Enthusiasm question Good 8 luck 26 22 30 Editorial Impressum 7 34 6 7 Editorial When I started my research for Emigre Magazin I wasn’t sure what to expect. Needless to say, I was impressed by Rudy VanderLans unconventional layouts and the enormous amount of different fonts created by Zuzana Licko. But apart from this I found more. While I went through the issues of Emigre in our library I stumbled over some ama- zing articles from different authors concerning various subjects of life per se as well as discussi- ons about graphic design. Finally, I came to issue #69, a summary of the whole Emigre story. I found myself confronted with testifies from Rudy VanderLans concerning the attitude, a graphic designer should have, and what it needs to be a designer, such as enthusi- asm and entrepreneurialism but also a little bit of luck. It became clear why Emigre was successfull almost two decades. As a student I thought these statements are really worth sharing and therefo- re I centered my attention in this folder on Rudy VanderLans quotations. 8 Ex plo ra tion Be tired of the monotony of traditional typography E Elments of the Emigre cover issue # 14, 1985 11 10Exploration „ The first issue was put Early explorers of new technology together in 1984 in an We wanted to explore a more 11.5″ by 17″ format by VanderLans and two other Dutch immigrants, expressive, individualized Marc and Menno. -

Books & Printing in the Netherlands 1998

Mathieu Lommen Books &Printingin theNetherlands 1998 january On 16 January graphic designer Ben Bos was appointed honorary member of the bno [Beroepsorganisatie Nederlandse Ontwerpers – the Professional Association of Dutch Designers]. On this occasion a full-colour yer appeared. Bos was also the ini- tiator and rst chairman of the nago [Nederlands Archief Gra sch Ontwerpers – Dutch Graphic Designers Archive]. Treasures from the Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica in Amsterdam were on view from 16 January to 21 February in the Bibliotheca Wittockiana in Brussels. [Undated press release] From 20 January to 30 March the Museum van het Boek/Museum Meermanno- Westreenianum in The Hague paid attention to the bibliophile publishing house Philip Elchers, which had been in existence for twelve and a half years. [Undated press release] On 28 January the graphic designer and publicist Fons van der Linden (b. 1923) passed away in his place of residence ’s-Hertogenbosch. An obituary by A.S.A. Struik appeared in De Boekenwereld , 144 (1998), and one by Karel F. Treebus in Quærendo, 29/4 (1999). From 29 January to 12 April there were two exhibitions on view in the Museum van het Boek/Museum Meermanno-Westreenianum in The Hague: ‘W.J. Rozendaal (1899-1971): gra sch werk’ and ‘Susanne Gruber-Heynemann: text design & typo- gra e’. Rozendaal, artist and book designer, taught drawing and painting at the Royal Academy of Visual Arts in The Hague during the years 1937-60. On the occasion of this exhibition the monograph W.J. Rozendaal ( 1899-1971) (208 pp.) appeared, pub- lished by De Walburg Pers. Later in the year the museum of Glasfabriek Leerdam was to pay attention to Rozendaal as a designer of services, vases and commemo- rative plates.