Land Use Management and Airport Controls: a Further Study of Trends and Indicators of Incompatible Land

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 AIR MONITORING NETWORK PLAN July 1, 2017

METEOROLOGY, MEASUREMENT AND RULES DIVISION 2016 AIR MONITORING NETWORK PLAN July 1, 2017 Charles Knoderer Duc Nguyen Dan Alrick and Katherine Hoag Meteorology, Measurements and Rules Division 375 Beale St., Suite 600, San Francisco, CA 94105 This page intentionally left blank. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page 1. ...... INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 11 2. ...... OVERVIEW OF NETWORK OPERATION .................................................................................... 11 2.1 ... Network Design ..................................................................................................................... 11 2.2 ... Minimum Monitoring Requirements ............................................................................. 17 Monitoring Agreements with Yolo/Solano AQMD and Northern Sonoma APCD ........................................................................................... 19 Monitoring Agreements with Monterey Bay Unified APCD .................... 19 2.2.1 Minimum Monitoring Requirements for Ozone .......................................... 19 Ozone Monitoring Season Waivers and Waiver Request ......................... 22 Napa Ozone Spatial Scale, Waiver Request ................................................... 22 2.2.2 Minimum Monitoring Requirements for PM2.5 ............................................. 23 State Implementation Plan (SIP) Requirements ........................................... 23 -

FREMONT BLVD Property FREMONT, CA FREMONT Highlights BLVD FREMONT, CA

48401 48401 FREMONT BLVD property FREMONT, CA FREMONT highlights BLVD FREMONT, CA CONSTRUCTION COMPLETE! VIEW VIDEO OF 48401 FREMONT ±209,926 SF BOULEVARD STATE-OF-THE-ART VIEW TIME-LAPSE VIDEO OF CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRIAL BUILDING NICK LAZZARINI | 408.615.3410 | [email protected] | LIC #01788935 DREW ARVAY | 408.436.3647 | [email protected] | LIC #00511262 VICTOR DEBOER | 510.891.5804 | [email protected] | LIC #01910482 48401 Site Plan FREMONT BLVD FREMONT, CA F R E M O N T B O U L E V A R D 35’ 26’ 35’ • ±209,926 SF Total • ± ELECTRICAL 11,290 SF Spec Office (Two-Stories) PRIMARY OFFICE WITH ROOM POTENTIAL 2ND STORY OFFICE PUMP ROOM OFFICE • 339 Parking Stalls • 14’ 33’ 14’ 694’ 23 Dock Doors / 2 Grade Level Doors • 36’ Clear Height BUILDING AREA • ESFR Sprinkler System 209,926 S.F. 283’ 343’ • 4,000 Amps at 277/480V 56’ TYP • 130’ Truck Court Depth • 2.0% Skylight Ratio 23 DOCK DOORS • 8” Slab 60’ • 4 - 40,000 LB Pit Levelers 17’ 32’ 17’ 130’ DOWNLOAD BROCHURE NICK LAZZARINI | 408.615.3410 | [email protected] | LIC #01788935 DREW ARVAY | 408.436.3647 | [email protected] | LIC #00511262 VICTOR DEBOER | 510.891.5804 | [email protected] | LIC #01910482 48401 FREMONT BLVD Office Floor Plans FREMONT, CA GROUND FLOOR SECOND FLOOR NICK LAZZARINI | 408.615.3410 | [email protected] | LIC #01788935 DREW ARVAY | 408.436.3647 | [email protected] | LIC #00511262 VICTOR DEBOER | 510.891.5804 | [email protected] | LIC #01910482 48401 FREMONT BLVD Amenity Map FREMONT, CA X ON -

FAA Annual Runway Safety Report 2009

Air Traffic Organization Annual Runway Federal Aviation Administration 800 Independence Avenue, SW Safety Report 2009 Washington, DC 20591 2009-AJS-129 A Message from the FAA Administrator Dear Colleagues: We’re making progress on the issue of runway safety, but as an agency and as an industry, we need to do more. This report details the strides we’ve made over the last year. It also includes our next steps to take what is arguably one of the safest locations in all of aviation— a U.S. runway— and make it safer still. In the long term, runway safety is very, very good. Last year, we had 25 serious runway incursions. That’s out of more than 58 million operations. Serious runway incursions have dropped by more than half since 2001. Nine of those 25 serious incursions last year involved commercial aircraft. The 25 incursions were up one from the previous year, which was an all-time low. But the 2008 totals show that we must increase our vigilance. Last year, runway incursions of all types increased by some 13 percent over 2007, rising from 891 to 1,009. So far in fiscal year 2009, the data look promising with a projected drop in total incursions for the full year by some five percent and an accompanying reduction in serious incursions by at least 50 percent. These data are encouraging. But while the actual runway incursion numbers are still a very thin slice of overall operations, as an aviation professional, I believe that very good is still not good enough. -

Sjc Airport South Flow Data for Q1 – 2021

2021 CITY OF SUNNYVALE Q1 – FLIGHT OPERATIONS AND NOISE REPORT CASPER AIRPORT SOLUTIONS, INC. | 1055 Westlakes Drive, Suite 300, Berwyn, PA 19312 | https://casper.aero DISCLAIMER Casper Airport Solutions, Inc. provides the data in this report on behalf of the City of Sunnyvale for informational purposes only. It has no legal standing and is not recognized as an official source by either the State of California or the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). The City of Sunnyvale is not an airport authority. It has no statutory reporting obligation under Title 21 of the California Department of Transportation. The sound level meters installed by Casper are certified by the manufacturer Larson Davis to meet all ANSI performance requirements for a Type 1 sound level meter. The FAA System Wide Information Management (SWIM) flight track position data has a stated minimum accuracy of + 150 feet and temporal accuracy of approximately 1 second. © 2021 Casper Airport Solutions, Inc. 1 INTRODUCTION The City of Sunnyvale's primary goal in procuring a Noise and Operations Monitoring System (NOMS) is to monitor flight activity and the aircraft noise associated with overflights that affect residents living within the city limits. Secondly, to provide this data to interested parties in a transparent and unfiltered way. The data contained in this report is presented with that goal in mind. On each page, you will find an explanation of how to read the various charts and definitions of the different metrics and data types. What you will not find is any interpretation by the “City” about the data in this report. -

Runway Safety Report Safety Runway

FAA Runway Safety Report Safety Runway FAA Runway Safety Report September 2007 September 2007 September Federal Aviation Administration 800 Independence Avenue SW Washington, DC 20591 www.faa.gov OK-07-377 Message from the Administrator The primary mission of the Federal Aviation Administration is safety. It’s our bottom line. With the aviation community, we have developed the safest mode of transportation in the history of the world, and we are now enjoying the safest period in aviation history. Yet, we can never rest on our laurels because safety is the result of constant vigilance and a sharp focus on our bottom line. Managing the safety risks in the National Airspace System requires a systematic approach that integrates safety into daily operations in control towers, airports and aircraft. Using this approach, we have reduced runway incursions to historically low rates over the past few years, primarily by increasing awareness and training and deploying new technologies that provide critical information directly to flight crews and air traffic controllers. Other new initiatives and technologies, as outlined in the 2007 Runway Safety Report, will provide a means to an even safer tomorrow. With our partners, FAA will continue working to eliminate the threat of runway incursions, focusing our resources and energies where we have the best chance of achieving success. To the many dedicated professionals in the FAA and the aviation community who have worked so tirelessly to address this safety challenge, I want to extend our deepest gratitude and appreciation for the outstanding work you have done to address this ever-changing and ever-present safety threat. -

Comprehensive Revitalization Plan for the Oroville Municipal Airport Fixed Base Operations (FBO) Facility

Comprehensive Revitalization Plan for the Oroville Municipal Airport Fixed Base Operations (FBO) Facility Pursuant to the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) Prepared By: Michael A. Hodges President and Chief Executive Officer & Randy D. Bisgard Senior Vice President Airport Business Solutions “Valuation and Consulting Services to the Aviation Industry” 13529 Prestige Place, Suite 108, Tampa, Florida 33635-9772 Phone (813) 269-2525 Fax (813) 269-8022 December 31, 2008 Ms. Sharon Atteberry City Administrator City of Oroville 1735 Montgomery Street Oroville, California 95965-4897 RE: Comprehensive Revitalization Plan For the Oroville Municipal Airport Fixed Base Operations (FBO) Facility Oroville, California Dear Ms. Atteberry: Per our engagement with the City of Oroville, we are pleased to present this Comprehensive Revitalization Plan for the Oroville Municipal Airport Fixed Base Operations (FBO) Facility. The following report provides our assessment and recommendations relative to current issues and future opportunities at the Airport, FBO, and within the community. The recommendations and requirements herein are included as possible actions for implementation to assist the City of Oroville in achieving their goals and objectives. In the development of this document, Airport Business Solutions researched many sectors of the local and regional general aviation market, specifically the northern California and Western region of the U.S. The goals and objectives of this Revitalization Plan for the Airport and FBO operations were to improve the financial situation of the Airport and the City and increase service demand, which will ultimately create new jobs in the area. Within this Revitalization Plan, recommendations and/or requirements are included as potential actions for implementation relating to the strategy contained herein. -

Regional Airport System Plan

Regional Airport System Plan General Aviation Element Final Report Regional Airport Planning Committee June 2003 REGIONAL AIRPORT SYSTEM PLAN GENERAL AVIATION ELEMENT FINAL REPORT Prepared for the Regional Airport Planning Committee of ABAG, BCDC, MTC The preparation of this report has been financed in part by grants from the Federal Aviation Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation. The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the official views or policy of the U.S. Department of Transportation. Prepared by ARIES CONSULTANTS LTD. Morgan Hill, California June 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page PART 1. REGIONAL INTERESTS AND PLAN RECOMMENDATIONS 1 OVERVIEW ................................................................................................. 1-1 1.1 Introduction......................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 What is General Aviation.................................................................... 1-4 1.3 Observations ....................................................................................... 1-4 1.4 Defining a Regional Interest ............................................................... 1-6 1.5 Recommendations............................................................................... 1-7 2 GENERAL AVIATION TRENDS AND ISSUES ..................................... 2-1 2.1 Introduction......................................................................................... 2-1 2.2 Airport System Requirements............................................................ -

Airport Rent Study-032917

Airport Rent Study City of Hayward Hayward Executive Airport T-HANGARS AND EXECUTIVE HANGARS March 29, 2017 March 29, 2017 Doug McNeeley Airport Manager Hayward Executive Airport 20301 Skywest Drive Hayward, California 94541 RE: Airport Rent Study Dear Mr. McNeeley: This summary report conveys Aviation Management Consulting Group’s (AMCG) opinion of market rent for certain improvements located at Hayward Executive Airport which are currently being leased or available for lease from the City of Hayward. AMCG is pleased to have been called on to conduct this study and provide an opinion of market rent. Please contact me if you have any questions pertaining to this analysis or the conclusions reached. Sincerely, David C. Benner Managing Consultant 9085 East Mineral Circle, Suite 315 Centennial, Colorado 80112 Phone 303 792 2700 Fax 303 792 2751 www.aviationmanagement.com TABLE OF CONTENTS I. LIMITING CONDITIONS .............................................................................................. 1 II. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................. 1 III. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 2 A. Scope of Work ...................................................................................................... 2 B. Market Rent Defined ............................................................................................ 2 C. Project Approach ................................................................................................. -

Palo Alto Arpt of Santa Clara Co Airport Title Manager of Maintenance and Operations 1925 Embarcadero Rd

NOISE ABATEMENT PROCEDURES by Whispertrack Noise Palo Alto Arpt Of Santa Clara Co Sensitivity HIGH KPAO Airport Level: Palo Alto, California, United States Diagram #1: Noise Abatement Procedures All Runways © Whispertrack™ 2009-2021. All rights reserved. p. 1 of 6 Generated 24 Sep 2021 at 14:01 UTC http://whispertrack.com/airports/KPAO NOISE ABATEMENT PROCEDURES by Whispertrack Noise Palo Alto Arpt Of Santa Clara Co Sensitivity HIGH KPAO Airport Level: Palo Alto, California, United States Diagram #2: Noise Abatement Procedures All Runways © Whispertrack™ 2009-2021. All rights reserved. p. 2 of 6 Generated 24 Sep 2021 at 14:01 UTC http://whispertrack.com/airports/KPAO NOISE ABATEMENT PROCEDURES by Whispertrack Noise Palo Alto Arpt Of Santa Clara Co Sensitivity HIGH KPAO Airport Level: Palo Alto, California, United States OVERVIEW Palo Alto Airport (airport) is located within one-half mile of Highway 101. Airport staff is dedicated to promoting aviation while working cooperatively with residents of Palo Alto and surrounding communities. The airport is owned and operated by the City of Palo Alto and is a general aviation field. In addition to being the tenth busiest single runway airport in California, it is a reliever to three Bay Area airports. The airport has one paved runway 13/31, which measures 2,443 × 70 feet. Palo Alto Airport Operations staff available from 7am to 9pm seven days a week. Air Traffic Control Tower operated by the Federal Aviation Administration. TEMPORARY INFORMATION Please stay connected with the City of Palo Alto regarding upcoming Construction activities. Please email [email protected] to be added to the distribution list. -

Runway 29 Turbojet Arrivals

Aircraft Over Flight and Noise Analysis At Norwood Drive Hayward, CA Prepared by Noise/Environmental Management Office Port of Oakland February 28, 2012 Norwood Drive Report Page 1 of 17 Aircraft Over Flight and Noise Analysis Norwood Drive, Hayward, CA The residents on Norwood Drive began registering their aircraft noise concerns with the airport during the fall of 2010. The residents expressed their belief that aircraft overflights and noise had increased dramatically over the past year or so. In response to these concerns, Oakland International Airport, the Noise/Environmental Management Office performed a comprehensive aircraft over flight and noise study. Aircraft Noise Terminology/Metrics Appendix A defines the aircraft noise terminology used in this report. Location and Concerns Norwood Drive, Hayward is located approximately 11 miles southeast of Oakland International Airport. (See Figure 1.) This neighborhood lies generally below the straight-in final approach course for Runway 27L/R and the Pacific Northwest arrivals into Runway 29, at Oakland International Airport. This final approach course has been used since the runway opened in 1962. Aircraft Flight Information Runway 29 is used for aircraft arrivals and departures when the Bay Area is being operated in the West Plan air traffic pattern. Air traffic patterns are a function of the wind conditions and the prevailing winds are blowing from the west and northwest in the Bay Area the majority of the time. The West Plan air traffic pattern is maintained by FAA Air Traffic Control about 90% of the time throughout the year; otherwise the Southeast Plan is in effect. When the Southeast Plan is in effect, Runway 11 is used and aircraft arrive from the north and northeast and depart to the south and southeast. -

Portable Noise Monitoring Report

SAN FRANCISCO INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT CITY & COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO MEMORANDUM TO: EAST PALO ALTO COMMUNITY FROM: SAN FRANCISCO INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT AIRCRAFT NOISE OFFICE SUBJECT: 2020 EAST PALO ALTO NOISE MONITORING REPORT #2 DATE: MAY 21, 2021 The San Francisco International Airport (SFO) Aircraft Noise Abatement Office conducted aircraft noise monitoring in East Palo Alto to determine noise levels within the community from aircraft operations at SFO. This measurement period was from December 16, 2020 to December 29, 2020. The monitoring was made possible with the assistance of the City of East Palo Alto Public Works Director and Engineering Staff. The overall average daily noise level from all aircraft was 48dBA CNEL. The Community daily noise level was 59dBA CNEL. The noise monitor thresholds were 60dBA for daytime and 53dBA for nighttime. The monitoring site on University Avenue had exposure to roadway traffic on University Avenue. The site was located in a busy area but was situated on a roof so that it was exposed to less community noise. The ambient noise level of the site was 54dBA. On an average day there were 405 overflights, out of which 62 exceeded the noise monitor threshold and recorded a noise event. The majority of flights was traffic out of nearby Palo Alto Airport (PAO) and SFO arrivals merging onto the final approach course for Runways 28L and 28R. Most of the SFO arrivals overflew at altitudes between 3,500 feet and 4,500 feet. SFO traffic represented approximately 45% of all aircraft noise events over the area. Approximately 49% of aircraft noise events were attributed to general aviation operations out of PAO. -

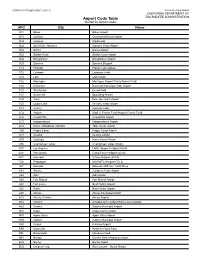

CDTFA-810-FTH Airport Code Table

CDTFA-810-FTH (S1F) REV. 1 (10-17) STATE OF CALIFORNIA CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF Airport Code Table TAX AND FEE ADMINISTRATION (Sorted by Airport Code) APC City Name 0O2 Baker Baker Airport 0O4 Corning Corning Municipal Airport 0O9 Gasquet Ward Field 0Q3 Schellville / Sonoma Sonoma Valley Airport 0Q4 Selma Selma Airport 0Q5 Shelter Cove Shelter Cove Airport 0Q6 Shingletown Shingletown Airport 0Q9 Sonoma Sonoma Skypark 1C9 Hollister Frazier Lake Airpark 1O2 Lakeport Lampson Field 1O3 Lodi Lodi Airport 1O5 Montague Montague Airport (Yreka Rohrer Field) 1O6 Dunsmuir Dunsmuir Municipal-Mott Airport 1Q1 Strathmore Eckert Field 1Q2 Susanville Spaulding Airport 1Q4 Tracy New Jerusalem Airport 1Q5 Upper Lake Gravelly Valley Airport 2O1 Quincy Gansner Field 2O3 Angwin Virgil O. Parrett Field (Angwin-Parrett Field) 2O6 Chowchilla Chowchilla Airport 2O7 Independence Independence Airport 2Q3 Davis / Woodland / Winters Yolo County Airport 36S Happy Camp Happy Camp Airport 3O1 Gustine Gustine Airport 3O8 Coalinga Harris Ranch Airport 49X Chemehuevi Valley Chemehuevi Valley Airport 4C0* Los Angeles LAPD Hooper Heliport (4CA0) 4C3* Pleasanton Camp Parks Heliport (4CA3) 60C* Concord Q Area Heliport (60CA) 7C4* Bridgeport MCMWTC Heliport (7CL4) 9L2 Edwards Edwards AFB Aux. North Base A24 Alturas California Pines Airport A26 Adin Adin Airport A28 Fort Bidwell Fort Bidwell Airport A30 Fort Jones Scott Valley Airport A32 Dorris Butte Valley Airport AAT Alturas Alturas Municipal Airport ACV Arcata / Eureka Arcata Airport AHC Herlong Amedee Army Airfield (Sierra Army Depot) AJO Corona Corona Municipal Airport APC Napa Napa County Airport APV Apple Valley Apple Valley Airport AUN Auburn Auburn Municipal Airport AVX Avalon Catalina Airport BAB Marysville Beale Air Force Base BFL Bakersfield Meadows Field BIH Bishop Eastern Sierra Regional Airport BLH Blythe Blythe Airport BLU Emigrant Gap Blue Canyon - Nyack Airport CDTFA-810-FTH (S1B) REV.