Association Between Regular Aspirin Use and Circulating Markers of Inflammation: a Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complementary DNA Microarray Analysis of Chemokines and Their Receptors in Allergic Rhinitis RX Zhang,1 SQ Yu,2 JZ Jiang,3 GJ Liu3

RX Zhang, et al ORIGINAL ARTICLE Complementary DNA Microarray Analysis of Chemokines and Their Receptors in Allergic Rhinitis RX Zhang,1 SQ Yu,2 JZ Jiang,3 GJ Liu3 1 Department of Otolaryngology, Huadong Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, China 2 Department of Otolaryngology , Jinan General Hospital of PLA, Shandong, China 3 Department of Otolaryngology, Changhai Hospital, Second Military Medical University, Shanghai, China ■ Abstract Objective: To analyze the roles of chemokines and their receptors in the pathogenesis of allergic rhinitis by observing the complementary DNA (cDNA) expression of the chemokines and their receptors in the nasal mucosa of patients with and without allergic rhinitis, using gene chips. Methods: The total RNAs were isolated from the nasal mucosa of 20 allergic rhinitis patients and purifi ed to messenger RNAs, and then reversely transcribed to cDNAs and incorporated with samples of fl uorescence-labeled with Cy5-dUPT (rhinitis patient samples) or Cy3- dUTP (control samples of nonallergic nasal mucosa). Thirty-nine cDNAs of chemokines and their receptors were latticed into expression profi le chips, which were hybridized with probes and then scanned with the computer to study gene expression according to the different fl uorescence intensities. Results: The cDNAs of the following chemokines were upregulated: CCL1, CCL2, CCL5, CCL7, CCL8, CCL11, CCL13, CCL14, CCL17, CCL18, CCL19, CCL24, and CX3CL1 in most of the allergic rhinitis sample chips. CCR2, CCR3, CCR4, CCR5, CCR8 and CX3CR1 were the highly expressed receptor genes. Low expression of CXCL4 was found in these tissues. Conclusion: The T helper cell (TH) immune system is not well regulated in allergic rhinitis. -

Anti-CCL13 / MCP4 Antibody (Biotin) (ARG65993)

Product datasheet [email protected] ARG65993 Package: 50 μg anti-CCL13 / MCP4 antibody (Biotin) Store at: 4°C Summary Product Description Biotin-conjugated Goat Polyclonal antibody recognizes CCL13 / MCP4 Tested Reactivity Hu Tested Application ELISA, WB Host Goat Clonality Polyclonal Isotype IgG Target Name CCL13 / MCP4 Antigen Species Human Immunogen E. coli derived recombinant Human CCL13 / MCP4. (QPDALNVPST CCFTFSSKKI SLQRLKSYVI TTSRCPQKAV IFRTKLGKEI CADPKEKWVQ NYMKHLGRKA HTLKT) Conjugation Biotin Alternate Names SCYA13; C-C motif chemokine 13; Monocyte chemotactic protein 4; Small-inducible cytokine A13; CKb10; SCYL1; Monocyte chemoattractant protein 4; MCP-4; NCC-1; NCC1; CK-beta-10 Application Instructions Application table Application Dilution ELISA Direct: 0.25 - 1.0 µg/ml Sandwich: 0.25 - 1.0 µg/ml with ARG65992 as a capture antibody WB 0.1 - 0.2 µg/ml Application Note * The dilutions indicate recommended starting dilutions and the optimal dilutions or concentrations should be determined by the scientist. Calculated Mw 11 kDa Properties Form Liquid Purification Purified by affinity chromatography. Buffer PBS (pH 7.2) Concentration 1 mg/ml Storage instruction Aliquot and store in the dark at 2-8°C. Keep protected from prolonged exposure to light. Avoid repeated freeze/thaw cycles. Suggest spin the vial prior to opening. The antibody solution should be gently mixed before use. Note For laboratory research only, not for drug, diagnostic or other use. www.arigobio.com 1/2 Bioinformation Database links GeneID: 6357 Human Swiss-port # Q99616 Human Gene Symbol CCL13 Gene Full Name chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 13 Background This antimicrobial gene is one of several Cys-Cys (CC) cytokine genes clustered on the q-arm of chromosome 17. -

Part One Fundamentals of Chemokines and Chemokine Receptors

Part One Fundamentals of Chemokines and Chemokine Receptors Chemokine Receptors as Drug Targets. Edited by Martine J. Smit, Sergio A. Lira, and Rob Leurs Copyright Ó 2011 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim ISBN: 978-3-527-32118-6 j3 1 Structural Aspects of Chemokines and their Interactions with Receptors and Glycosaminoglycans Amanda E. I. Proudfoot, India Severin, Damon Hamel, and Tracy M. Handel 1.1 Introduction Chemokines are a large subfamily of cytokines (50 in humans) that can be distinguished from other cytokines due to several features. They share a common biological activity, which is the control of the directional migration of leukocytes, hence their name, chemoattractant cytokines. They are all small proteins (approx. 8 kDa) that are highly basic, with two exceptions (MIP-1a, MIP-1b). Also, they have a highly conserved monomeric fold, constrained by 1–3 disulfides which are formed from a conserved pattern of cysteine residues (the majority of chemokines have four cysteines). The pattern of cysteine residues is used as the basis of their division into subclasses and for their nomenclature. The first class, referred to as CXC or a-chemokines, have a single residue between the first N-terminal Cys residues, whereas in the CC class, or b-chemokines, these two Cys residues are adjacent. While most chemokines have two disulfides, the CC subclass also has three members that contain three. Subsequent to the CC and CXC families, two fi additional subclasses were identi ed, the CX3C subclass [1, 2], which has three amino acids separating the N-terminal Cys pair, and the C subclass, which has a single disulfide. -

Recombinant Human MCP-4 / CCL13 (Monocyte Chemotactic Protein-4)

Recombinant Human MCP-4 / CCL13 (Monocyte Chemotactic Protein-4) Catalog Number: 100-132 Accession Number: Q99616 Specifications and Uses: Alternate Names: CCL13, NCC-1 Description: Monocyte Chemotactic Protein 4 (MCP-4), also called CCL13, is induced by inflammatory proteins such as IL-1 and TNFα. MCP-4 is a ligand for three different G protein coupled receptors, CCR2, CCR3 and CCR5. MCP-4 activates signaling in monocytes, T lymphocytes, eosinophils and basophils and this signaling is associated with the allergic response. Recombinant human MCP-4 is a non-glycosylated protein, containing 74 amino acids, with a molecular weight of 8.5 kDa. Source: E.coli Physical Appearance: Sterile filtered white lyophilized (freeze-dried) powder. Formulation and Stability: Recombinant human MCP-4 is lyophilized with no additives. Lyophilized product is very stable at -20°C. Reconstituted material should be aliquoted and frozen at -20°C. It is recommended that a carrier protein (0.1% HSA or BSA) is added for long term storage. Reconstitution: Centrifuge vial before opening. When reconstituting the product, gently pipet and wash down the sides of the vial to ensure full recovery of the protein into solution. It is recommended to reconstitute the lyophilized product with sterile water at a concentration of 0.1 mg/mL, which can be further diluted into other aqueous solutions. Protein Content and Purity (typically ≥ 95%) determined by: HPLC, Reducing and Non-reducing SDS-PAGE, UV spectroscopy at 280 nm Endotoxin Level: Measured by kinetic LAL analysis and is typically ≤ 1 EU/μg protein. Biological Activity: The biological activity is determined by the ability of MCP-4 to chemoattract human monocytes and is typically between 7– 75 ng/mL. -

Chemokine Receptors and Chemokine Production by CD34+ Stem Cell-Derived Monocytes in Response to Cancer Cells

ANTICANCER RESEARCH 32: 4749-4754 (2012) Chemokine Receptors and Chemokine Production by CD34+ Stem Cell-derived Monocytes in Response to Cancer Cells MALGORZATA STEC, JAROSLAW BARAN, MONIKA BAJ-KRZYWORZEKA, KAZIMIERZ WEGLARCZYK, JOLANTA GOZDZIK, MACIEJ SIEDLAR and MAREK ZEMBALA Department of Clinical Immunology and Transplantation, Polish-American Institute of Paediatrics, Jagiellonian University Medical College, Cracow, Poland Abstract. Background: The chemokine-chemokine receptor The chemokine–chemokine receptor (CR) network is involved (CR) network is involved in the regulation of cellular in the regulation of leukocyte infiltration of tumours. infiltration of tumours. Cancer cells and infiltrating Leukocytes, including monocytes, migrate to the tumour via macrophages produce a whole range of chemokines. This the gradient of chemokines that are produced by tumour and study explored the expression of some CR and chemokine stromal cells, including monocyte-derived macrophages (1-4). production by cord blood stem cell-derived CD34+ Several chemokines are found in the tumour microenvironment monocytes and their novel CD14++CD16+ and and are involved in the regulation of tumour-infiltrating CD14+CD16– subsets in response to tumour cells. Material macrophages (TIMs), by controlling their directed migration to and Methods: CR expression was determined by flow the tumour and inhibiting their egress by regulation of cytometry and their functional activity by migration to angiogenesis and immune response to tumour cells and by chemoattractants. -

Subclassification of Patients with Acute Myelogenous Leukemia Based On

Research Paper Subclassification of patients with acute myelogenous leukemia based on chemokine responsiveness and constitutive chemokine release by their leukemic cells Øystein Bruserud, Anita Ryningen, Astrid Marta Olsnes, Laila Stordrange, Anne Margrete Øyan, Karl Henning Kalland, Bjørn Tore Gjertsen ABSTRACT From the Division for Hematology, Background and Objectives Department of Medicine, Haukeland University Hospital Chemokines are soluble mediators involved in angiogenesis, cellular growth control and The University of Bergen, and immunomodulation. In the present study we investigated the effects of various Bergen, Norway (OB, AR, AMartO, chemokines on proliferation of acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) cells and consti- BTG); Department of Informatics, tutive chemokine release by primary AML cells. The University of Bergen, Norway (LS); The Gade Institute, Haukeland Design and Methods University Hospital and The Native human AML cells derived from 68 consecutive patients were cultured in vitro. University of Bergen, Norway 3 (AMargO, KHK). We investigated AML cell proliferation ( H-thymidine incorporation, colony formation), chemokine receptor expression, constitutive chemokine release and chemotaxis of Funding: this work was supported by normal peripheral blood mononuclear cells. the Norwegian Cancer Society. Results Acknowledgments: the technical Exogenous chemokines usually did not have any effect on AML blast proliferation in assistance of Kristin Paulsen and the absence of hematopoietic growth factors, but when investigating growth factor- Aina Kvinsland is gratefully acknowl- dependent (interleukin 3 + granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor + stem edged. cell factor) proliferation in suspension cultures the following patient subsets were identified: (i) patients whose cells showed chemokine-induced growth enhancement Manuscript received April 11, 2006. Manuscript accepted February 5, (8 patients); (ii) divergent effects on proliferation (15 patients); and (iii) no effect 2007. -

Reprogramming of Monocytes by GM-CSF Contributes to Regulatory Immune Functions During Intestinal Inflammation

The Journal of Immunology Reprogramming of Monocytes by GM-CSF Contributes to Regulatory Immune Functions during Intestinal Inflammation ,†,‡, ,1 ,1 Jan Da¨britz,* x Toni Weinhage,* Georg Varga,* Timo Wirth,* Karoline Walscheid,* ,‖ # # Anne Brockhausen,{ David Schwarzmaier,* Markus Bruckner,€ Matthias Ross, # †,‖ †, ,† Dominik Bettenworth, Johannes Roth, Jan M. Ehrchen, { and Dirk Foell* Human and murine studies showed that GM-CSF exerts beneficial effects in intestinal inflammation. To explore whether GM-CSF mediates its effects via monocytes, we analyzed effects of GM-CSF on monocytes in vitro and assessed the immunomodulatory potential of GM-CSF–activated monocytes (GMaMs) in vivo. We used microarray technology and functional assays to charac- terize GMaMs in vitro and used a mouse model of colitis to study GMaM functions in vivo. GM-CSF activates monocytes to increase adherence, migration, chemotaxis, and oxidative burst in vitro, and primes monocyte response to secondary microbial stimuli. In addition, GMaMs accelerate epithelial healing in vitro. Most important, in a mouse model of experimental T cell– induced colitis, GMaMs show therapeutic activity and protect mice from colitis. This is accompanied by increased production of IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13, and decreased production of IFN-g in lamina propria mononuclear cells in vivo. Confirming this finding, GMaMs attract T cells and shape their differentiation toward Th2 by upregulating IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13 in T cells in vitro. Beneficial effects of GM-CSF in Crohn’s disease may possibly be mediated through reprogramming of monocytes to simulta- neously improved bacterial clearance and induction of wound healing, as well as regulation of adaptive immunity to limit excessive inflammation. -

![View to Dispar [1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6938/view-to-dispar-1-2346938.webp)

View to Dispar [1]

Lechner et al. Immunity & Ageing 2013, 10:29 http://www.immunityageing.com/content/10/1/29 IMMUNITY & AGEING RESEARCH Open Access Cytokine and chemokine responses to helminth and protozoan parasites and to fungus and mite allergens in neonates, children, adults, and the elderly Christian J Lechner1†, Karl Komander1†, Jana Hegewald1, Xiangsheng Huang1, Richard G Gantin1,2, Peter T Soboslay1,2, Abram Agossou4, Meba Banla3 and Carsten Köhler1* Abstract Background: In rural sub-Saharan Africa, endemic populations are often infected concurrently with several intestinal and intravascular helminth and protozoan parasites. A specific, balanced and, to an extent, protective immunity will develop over time in response to repeated parasite encounters, with immune responses initially being poorly adapted and non-protective. The cellular production of pro-inflammatory and regulatory cytokines and chemokines in response to helminth, protozoan antigens and ubiquitous allergens were studied in neonates, children, adults and the elderly. Results: In children schistosomiasis prevailed (33%) while hookworm and Entamoeba histolytica/E. dispar was found in up to half of adults and the elderly. Mansonella perstans filariasis was only present in adults (24%) and the elderly (25%). Two or more parasite infections were diagnosed in 41% of children, while such polyparasitism was present in 34% and 38% of adults and the elderly. Cytokine and chemokine production was distinctively inducible by parasite antigens; pro-inflammatory Th2-type cytokine IL-19 was activated by Entamoeba and Ascaris antigens, being low in neonates and children while IL-19 production enhanced “stepwise” in adults and elderly. In contrast, highest production of MIP-1delta/CCL15 was present in neonates and children and inducible by Entamoeba-specific antigens only. -

An Introduction to Chemokines and Their Roles in Transfusion Medicine

Vox Sanguinis (2009) 96, 183–198 © 2008 The Author(s) REVIEW Journal compilation © 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd. DOI: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2008.01127.x AnBlackwell Publishing Ltd introduction to chemokines and their roles in transfusion medicine R. D. Davenport Blood Bank and Transfusion Service, University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor, MI, USA Chemokines are a set of structurally related peptides that were first characterized as chemoattractants and have subsequently been shown to have many functions in homeostasis and pathophysiology. Diversity and redundancy of chemokine function is imparted by both selectivity and overlap in the specificity of chemokine receptors for their ligands. Chemokines have roles impacting transfusion medicine in haemat- opoiesis, haematologic malignancies, transfusion reactions, graft-versus-host disease, and viral infections. In haematopoietic cell transplantation, chemokines are active in mobilization and homing of progenitor cells, as well as mediating T-cell recruitment in graft-versus-host disease. Platelets are rich source of chemokines that recruit and activate leucocytes during thrombosis. Important transfusion-transmissible viruses such as cytomegalovirus and human immunodeficiency virus exploit chemokine receptors to evade host immunity. Chemokines may also have roles in the pathophysiology of Received: 4 June 2007, revised 29 September 2008, haemolytic and non-haemolytic transfusion reactions. accepted 16 October 2008, Key words: Chemokines, chemokine receptors, haematopoietic stem cell transplantation, published online 8 December 2008 graft-vs-host disease, transfusion reactions. General characteristics of chemokines This classification is not completely definite, as under some conditions homeostatic chemokines are inducible. Chemokines are small, secreted proteins in the range of 8– Most chemokines were originally named for their first 10 kDa that have numerous functions in normal physiology identified biological activity, such as monocyte chemoattractant and pathology. -

Explorations Into Host Defense Against Plasmodium Falciparum: Mechanistic and Structure-Function Studies of Antimalarial Chemokines

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2014 Explorations into host defense against Plasmodium falciparum: mechanistic and structure-function studies of antimalarial chemokines Melissa Suzanne Love University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Biochemistry Commons, Parasitology Commons, and the Pharmacology Commons Recommended Citation Love, Melissa Suzanne, "Explorations into host defense against Plasmodium falciparum: mechanistic and structure-function studies of antimalarial chemokines" (2014). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1352. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1352 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1352 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Explorations into host defense against Plasmodium falciparum: mechanistic and structure-function studies of antimalarial chemokines Abstract Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are small (2-8kDa) peptides that have remained an important part of innate immunity over evolutionary time. AMPs vary greatly in sequence and structure, but display broad- spectrum activity against bacteria, yeast, and fungi via direct perturbation of the pathogen membrane. AMPs are typically amphipathic, and contain 2-4 positively charged amino acid residues. It has been previously shown that many chemokines also display AMP activity, both via their canonical function recruiting immune cells to the site of an infection and by direct interaction with the pathogen itself. Many antimicrobial chemokines have the same tertiary structure: an N-terminal loop responsible for receptor recognition; a three-stranded antiparallel β-sheet domain that provides a stable scaffold; and a C-terminal α-helix that folds over the β-sheet and helps to stabilize the overall structure. -

During Intestinal Inflammation Functions Contributes to Regulatory

Reprogramming of Monocytes by GM-CSF Contributes to Regulatory Immune Functions during Intestinal Inflammation This information is current as Jan Däbritz, Toni Weinhage, Georg Varga, Timo Wirth, of October 2, 2021. Karoline Walscheid, Anne Brockhausen, David Schwarzmaier, Markus Brückner, Matthias Ross, Dominik Bettenworth, Johannes Roth, Jan M. Ehrchen and Dirk Foell J Immunol published online 4 February 2015 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/early/2015/02/04/jimmun ol.1401482 Downloaded from Supplementary http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2015/02/04/jimmunol.140148 Material 2.DCSupplemental http://www.jimmunol.org/ Why The JI? Submit online. • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication by guest on October 2, 2021 *average Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2015 by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. Published February 4, 2015, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1401482 The Journal of Immunology Reprogramming of Monocytes by GM-CSF Contributes to Regulatory Immune Functions during Intestinal Inflammation Jan Da¨britz,*,†,‡,x,1 Toni Weinhage,*,1 Georg Varga,* Timo Wirth,* Karoline Walscheid,* Anne Brockhausen,{,‖ David Schwarzmaier,* Markus Bruckner,€ # Matthias Ross,# Dominik Bettenworth,# Johannes Roth,†,‖ Jan M. -

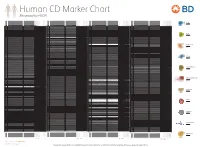

Reviewed by HLDA1

Human CD Marker Chart Reviewed by HLDA1 T Cell Key Markers CD3 CD4 CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD8 CD1a R4, T6, Leu6, HTA1 b-2-Microglobulin, CD74 + + + – + – – – CD74 DHLAG, HLADG, Ia-g, li, invariant chain HLA-DR, CD44 + + + + + + CD158g KIR2DS5 + + CD248 TEM1, Endosialin, CD164L1, MGC119478, MGC119479 Collagen I/IV Fibronectin + ST6GAL1, MGC48859, SIAT1, ST6GALL, ST6N, ST6 b-Galactosamide a-2,6-sialyl- CD1b R1, T6m Leu6 b-2-Microglobulin + + + – + – – – CD75 CD22 CD158h KIR2DS1, p50.1 HLA-C + + CD249 APA, gp160, EAP, ENPEP + + tranferase, Sialo-masked lactosamine, Carbohydrate of a2,6 sialyltransferase + – – + – – + – – CD1c M241, R7, T6, Leu6, BDCA1 b-2-Microglobulin + + + – + – – – CD75S a2,6 Sialylated lactosamine CD22 (proposed) + + – – + + – + + + CD158i KIR2DS4, p50.3 HLA-C + – + CD252 TNFSF4,