The Founding of the Newberry Library Paul Finkelman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Award Honorary Doctorate Degrees Funding

10 Board Meeting January 31, 2019 AWARD HONORARY DEGREES, URBANA Action: Award Honorary Doctorate Degrees Funding: No New Funding Required The Senate of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign has recommended that honorary degrees be conferred on the following people at Commencement Exercises on May 11, 2019: Michael T. Aiken, former Chancellor of the University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign -- the honorary degree of Doctor of Science and Letters Chancellor Aiken was the sixth chancellor of the University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign, leading the campus from 1993 until his retirement in 2001. Only one chancellor has served longer. Dr. Aiken was devoted to the excellence of the Urbana campus and undertook many initiatives with a lasting impact still felt today. During Campaign Illinois, he worked to establish more than 100 new endowed faculty positions. He enhanced the undergraduate experience by increasing opportunities for students to study abroad, expanding the number of living/learning communities in the various student residence halls, developed discovery classes for first-year students, and instituted New Student Convocation. Chancellor Aiken worked toward the creation of Research Park on the south campus to provide a vibrant environment for the campus efforts in economic development and innovation. Dr. Aiken was key to establishing the Campustown 2000 Task Force to improve both the physical appearance of Campustown and its safety and livability. Dr. Aiken made a priority of building strong relationships between the university and the greater Champaign-Urbana community. During his tenure, and through his leadership, gateways were built at the boundaries of the campus to serve as doors and windows between the campus and the community. -

College and Research Libraries

ROBERT B. DOWNS The Role of the Academic Librarian, 1876-1976 . ,- ..0., IT IS DIFFICULT for university librarians they were members of the teaching fac in 1976, with their multi-million volume ulty. The ordinary practice was to list collections, staffs in the hundreds, bud librarians with registrars, museum cu gets in millions of dollars, and monu rators, and other miscellaneous officers. mental buildings, to conceive of the Combination appointments were com minuscule beginnings of academic li mon, e.g., the librarian of the Univer braries a centur-y ago. Only two univer sity of California was a professor of sity libraries in the nation, Harvard and English; at Princeton the librarian was Yale, held collections in ·excess of professor of Greek, and the assistant li 100,000 volumes, and no state university brarian was tutor in Greek; at Iowa possessed as many as 30,000 volumes. State University the librarian doubled As Edward Holley discovered in the as professor of Latin; and at the Uni preparation of the first article in the versity of · Minnesota the librarian present centennial series, professional li served also as president. brarHms to maintain, service, and devel Further examination of university op these extremely limited holdings catalogs for the last quarter of the nine were in similarly short supply.1 General teenth century, where no teaching duties ly, the library staff was a one-man opera were assigned to the librarian, indicates tion-often not even on a full-time ba that there was a feeling, at least in some sis. Faculty members assigned to super institutions, that head librarians ought vise the library were also expected to to be grouped with the faculty. -

LHRT Newsletter LHRT Newsletter

LHRT Newsletter NOVEMBER 2010 VOLUME 10, ISSUE 1 BERNADETTE A. LEAR, EDITOR BAL19 @ PSU.EDU Greetings from the Chair BAL19 @ PSU.EDU and librarians. The week As we finalize details we will following Library History inform the membership as to Seminar XII, Wayne how they may participate. Wiegand threw down a challenge. He offered to It is time to turn to finding a contribute $100 to the venue for Library History Edward G. Holley Lecture Seminar XIII (2015). The endowment, and urged all request for proposals is previous LHRT Chairs and included in this newsletter. I Board members to do the invite LHRT members to same. In less than thirty- consider whether your six hours $2,400 was institution might be a good pledged. Ed’s son Jens was site. We are a community of one contributor (both to people with a love for the the fund and to this issue). histories of libraries, reading, His heartfelt message of print culture, and the people, thanks for honoring his places and institutions that are father in this way made me part of those histories. Why proud to be a member of not make a little bit of history LHRT. yourself by hosting this wonderful conference? The LHRT Program Committee is hard at work In the meantime, I will “see” to bring quality sessions to you virtually in January our annual meeting. We meeting in cyberspace, and see will have the Invited many of you in person at Speakers Panel, the ALA’s annual meeting in New Research Forum Panel, and Orleans in June. -

Cooperative and Centralized Cataloging and Processing: a Bibliography, 1850-1967

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 044 152 LI 002 209 AUTHOR Leonard, Lawrence E. TITLE Cooperative and Centralized Cataloging and Processing: A Bibliography, 1850-1967. INSTITUTION Illinois Univ., Urbana. Graduate School of Library Science. PUB DATE Jul 68 NOTE 92p.; Occasional Paper 93 EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.50 HC-$4.70 DESCRIPTORS Bibliographies, *Cataloging, *Library Acquisition, *Library Cooperation, *Library Technical Processes ABSTRACT Nine hundred and fifty-four references to articles on cooperative and ceatralized acquisitions, cataloging and processing, covering the period from 1850 to 1968, are included in this bibliography. Subject elements of the bibliography by the approximate date of appearance are:(1) Cooperative cataloging--1850-;(2) Centralized cataloging (Library of Congress card service--1900-, other centralized cataloging - - 1928 -); (3) Centralized purchasing--1919-; (4) Centralized processing--1948-; and (5) Cataloging-in-source--1958-1965. References to articles on "universal catalogs," "book catalogs," and "cooperative acquisitions programs" are not included here. An alphabetical author index is provided. (NH) slr 5- 4/7 University of Illinois Graduate School of Library Science OCCASIONAL PAPPI U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH.EDUCATION a WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THEPERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT. POINTSOF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DONOT NECES- SARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE0 P EDU- CATIONPOSITIONOR POLICY. COOPERATIVE AND CENTRALIZED CATALOGING AND PROCESSING:A -

Newberry Seminars Chicago Culture

SUMMER 2015 Newberry Seminars Chicago Culture Best Addresses: Notable Residential Streets in Chicago Tuesdays, 6:15 – 7:45 pm June 9 – August 4 (class will not meet July 7; we will meet from 6:15 – 8:15 pm on June 16) Through a series of walking tours, we will explore some of Chicago’s best addresses—streets known for significant domestic architecture, influential residents, or notable historical events. Examples will be drawn from a variety of neighborhoods, including Prairie Avenue, the Gold Coast, Streeterville, Lake Shore East, Lakeview, and Hyde Park. We will pay special attention to how residential architecture and urban design shape local identities as well as the way historic landmarks promote tourism, commerce, and design innovation. Only the Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, 1929. From first session will meet at the Newberry. Eight The Stanolind Record, a Standard Oil publication. sessions, $200. Newberry Midwest MS Barrett-Sandburg: Box 3, Folder 38 Diane Dillon holds a PhD in art history from Yale University and has been a regular seminar instructor post-meeting field trips to contemporary Chicago at the Newberry since 2003. establishments that illustrate the evening’s conversation. Six sessions, $180. Chicago Playwrights and Their Plays Bill Savage is associate professor of instruction at Tuesdays, 6 – 7:30 pm Northwestern University and has taught Newberry June 9 – July 28 Seminars since 1992. He has also worked in area bars This seminar offers the unique opportunity to since 1980. meet Chicago-based playwrights, engage in an in-depth dialogue about their work, and gain an intimate glimpse into their creative process. -

DPLA Usage Statistics for January 31

Digital Public Library of America Analytics Digital Public Library of A… Go to report Illinois DPLA Stats Jan 31, 2020 - Feb 29, 2020 All Users 100.00% Sessions Total Illinois Items Viewed on DPLA Item Pages 1,019 % of Total: 0.30% (341,244) Total Illinois Items Viewed in Exhibitions 0 % of Total: 0.00% (341,244) Total Illinois Items Viewed in Primary Source Sets 0 % of Total: 0.00% (341,244) Total Illinois Click Throughs 890 % of Total: 0.26% (341,244) Total Illinois Events 1,909 % of Total: 0.56% (341,244) Total Illinois Items Viewed in DPLA (In Item Pages, Exhibitions, and Primary Source Sets) Total Events 150 100 50 … Feb 2 Feb 4 Feb 6 Feb 8 Feb 10 Feb 12 Feb 14 Feb 16 Feb 18 Feb 20 Feb 22 Feb 24 Feb 26 Feb 28 Total Illinois Click Throughs Total Events 100 50 … Feb 2 Feb 4 Feb 6 Feb 8 Feb 10 Feb 12 Feb 14 Feb 16 Feb 18 Feb 20 Feb 22 Feb 24 Feb 26 Feb 28 Top 10 Events by Contributing Institution Event Action Total Events Unique Events University of Illinois at Chicago 250 237 Newberry Library 193 177 University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library 193 175 Illinois State University 160 157 Chicago History Museum 88 86 Pullman State Historic Site 88 79 Southern Illinois University Carbondale 83 82 Chicago Public Library 66 61 Illinois State Historical Society 55 49 Northern Illinois University 47 46 Top 10 Illinois Events by Item Event Label Total Events Unique Events 712586ef98b840352ffa930ba99fd467 : Ku Klux Klan 15 12 061aac7d02d8f660088fdf1e97a1a22e : Fisherman, Cotton Spinners, Cheeseman, Bran Seller, Milk Seller, Maltese Lady 11 10 509f5485f2cc5346304b4b8932a65dcc : Jane Addams Hull House Association, Hull House 10 10 804f30ee5163869fa826e374ab6ac933 : Abbott Laboratories, The Abbot Alkaloidal Co. -

Illinois Statewide Delivery Directory

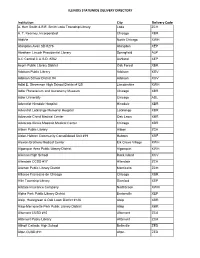

ILLINOIS STATEWIDE DELIVERY DIRECTORY Institution City Delivery Code A. Herr Smith & E.E. Smith Loda Township Library Loda ZCH A. T. Kearney, Incorporated Chicago XBR AbbVie North Chicago XWH Abingdon-Avon SD #276 Abingdon XEP Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library Springfield ALP A-C Central C.U.S.D. #262 Ashland XEP Acorn Public Library District Oak Forest XBR Addison Public Library Addison XGV Addison School District #4 Addison XGV Adlai E. Stevenson High School District #125 Lincolnshire XWH Adler Planetarium and Astronomy Museum Chicago XBR Adler University Chicago ADL Adventist Hinsdale Hospital Hinsdale XBR Adventist LaGrange Memorial Hospital LaGrange XBR Advocate Christ Medical Center Oak Lawn XBR Advocate Illinois Masonic Medical Center Chicago XBR Albion Public Library Albion ZCA Alden-Hebron Community Consolidated Unit #19 Hebron XRF Alexian Brothers Medical Center Elk Grove Village XWH Algonquin Area Public Library District Algonquin XWH Alleman High School Rock Island XCV Allendale CCSD #17 Allendale ZCA Allerton Public Library District Monticello ZCH Alliance Francaise de Chicago Chicago XBR Allin Township Library Stanford XEP Allstate Insurance Company Northbrook XWH Alpha Park Public Library District Bartonville XEP Alsip, Hazelgreen & Oak Lawn District #126 Alsip XBR Alsip-Merrionette Park Public Library District Alsip XBR Altamont CUSD #10 Altamont ZCA Altamont Public Library Altamont ZCA Althoff Catholic High School Belleville ZED Alton CUSD #11 Alton ZED ILLINOIS STATEWIDE DELIVERY DIRECTORY AlWood CUSD #225 Woodhull -

In Resistance to a Capitalist Past: Emerging Practices of Critical Librarianship Lua Gregory and Shana Higgins

In Resistance to a Capitalist Past: Emerging Practices of Critical Librarianship Lua Gregory and Shana Higgins Introduction In previous work, we’ve explored capitalism and neoliberal ideology in relation to oppression and inequalities, how consciousness raising as defned by Paulo Freire and Ira Shor can lead to informed action, and how the intersections of critical pedagogy and core values such as social responsibility, diversity, and the public good, can contextualize social justice work within the practice of librarianship.1 In this chapter, we revisit capitalism, by examining its inextricable historical connections to the proliferation of libraries and the growth of librarianship as a profession in the United States in the late nineteenth century. We fnd that the rise of capitalism and the “efciency movement” during the Progressive Era (1890–1920) led to a replicating of libraries in the image and model of corporations, and the creation of an educational system that favored practicality and connections to the market, within which we locate historical tensions between theory and practice. Tis chapter is neither historiography nor discourse analysis, but perhaps borrows from both. Our goal is to illuminate the economic and ideological contexts from which the library profession in the United States fourished, and has continued to be implicated. Despite the close alignment of American li- brarianship with a hegemonic economic ideology, there have been critical and 1 Lua Gregory and Shana Higgins, Information Literacy and Social Justice (Sacramento, CA: Library Juice Press, 2013). Te Politics of Teory and the Practice of Critical Librarianship resistant voices within the profession throughout the past century. -

History of Urban Main Library Service

History of Urban Main Library Service JACOB S. EPSTEIN THEMOST IMPORTANT early date for urban public libraries would certainly be 1854, the year the Boston Public Library opened its doors. But as Jesse Shera has noted: “The opening, on March 20,1854, of the reading room of the Boston Public Library. ..was not a signal that a new agency had suddenly been born into American urban life. Behind the act were more than two centuries of experimentation, uncertainty, and change.”l Before the advent of public libraries there were numerous social li- braries, mercantile libraries and other efforts to have a community store of books which could be borrowed or consulted. A common prin- ciple evident in each of them was the belief that the printed word was important and should be made available to the ordinary citizen who could not own all the literature which was of value. Although it was a subscription library, rather than a public library as we think of it today, Benjamin Franklin’s Library Company of Phila- delphia, organized in 1731, was the first library in America to circulate books and the first to pay a librarian for his services. In his Autobiogra- phy, Franklin declared, “These libraries have improved the general conversation of the Americans, made the common tradesmen and farm- ers as intelligent as most gentlemen from other countries, and perhaps have contributed in some degree to the stand so generally made throughout the colonies in defense of their privileges.”2 Here is that recurrent theme of self-improvement that runs throughout the Ameri- can public library movement. -

The Literature of American Library History, 2003–2005 Edward A

Collections and Technical Services Publications and Collections and Technical Services Papers 2008 The Literature of American Library History, 2003–2005 Edward A. Goedeken Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/libcat_pubs Part of the Library and Information Science Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ libcat_pubs/12. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Collections and Technical Services at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Collections and Technical Services Publications and Papers by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Literature of American Library History, 2003–2005 Abstract A number of years have elapsed since publication of the last essay of this sort, so this one will cover three years of historical writings on American librarianship, 2003–5, instead of the usual two. We will have to see whether this new method becomes the norm or will ultimately be considered an aberration from the traditional approach. I do know that several years ago Donald G. Davis, Jr., and Michael Harris covered three years (1971–73) in their essay, and we all survived the experience. In preparing this essay I discovered that when another year of coverage is added the volume of writings to cover also grows impressively. A conservative estimate places the number of books and articles published in the years under review at more than two hundred items. -

Bulletinofameric11amer.Pdf

' s*r THE UNIVERSITY r * - - - * ^ & >#*? OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY "> CW\ C > v- 5 wv i EMI BULLETIN OF THE AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION VOLUME V JANUARY-NOVEMBER, 1911 AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION 78 E. WASHINGTON STREET CHICAGO 1911 CONTENTS 1911 January MISCELLANEOUS March MISCELLANEOUS May MISCELLANEOUS July PROCEEDINGS OF THE PASADENA CONFERENCE September HANDBOOK, 1911 November. .MISCELLANEOUS INDEX A separate detailed index to the Proceedings of the Pasadena Conference is on pages 285-288 and its entries are not repeated here. Affiliated organizations, 309-10 Membership, benefits of, 291 Affiliation of A. L. A. with state library associa- Membership by states, 298 tions, report of committee on, 13-15 Necrology, 358 Bookbinding, report of committee on, 9, 26, New York state library, appeal for material, 45 45-6, 364 Officers, A. L. A., 1911-12, 301 Bostwick, Arthur E., attendance at Alabama Pasadena conference, travel announcements, library meeting, 360 1-2; 17-24; post-conference, 18-23; pro- Budget, A. L. A., 1911, 5 gram, 37-40 Charter, 290 Periodicals, list of library, 310 Chicago mid-winter meetings for 1912, an- Presidents, A. L. A., 299 nouncements of, 360-1 Publishing board, meeting, 6-8; budget, 1911, Clubs, library, 313-14 6-7; list of publications, 306-8 Committees, 1911-12, 303-5 Recorders, A. L. A., 300 Constitution, 291-6 Registrar, A. L. A., 300 Council, meeting of, 10-15; personnel of, 302-3 Secretaries, A. L. A., 300 Dues, 291 Sections, 308-9 Elmendorf, Mrs. H. L., attendance at Michi- State library conferences, A. L. A. at, 359-60 gan, Ohio and New York library meetings, State library associations, list of, 311-13 359 State library commissions, list of, 310-11 Endowment funds, 305 Stereopticon slides for library schools, 45 Executive board meeting, 3-6 Taylor, Mary W., resolution on death of, 9 Federal and state relations, report of com- Thwaites, Reuben G., represents A. -

Meet Carla Hayden Be a Media Mentor Connecting with Teens P. 34

November/December 2016 THE MAGAZINE OF THE AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION FAN FICTION! Connecting with teens p. 34 Meet Carla Hayden p. 40 Be a Media Mentor p. 48 PLUS: Snapchat, Midwinter Must-Dos, and Presidential Librarian APA JOURNALS® Give Your Users the Psychological Research They Need LEADING JOURNALS IN PSYCHOLOGY Practice Innovations Quarterly • ISSN: 2377-889X • www.apa.org/pubs/journals/pri Serves practitioners by publishing clinical, practical, and research articles on current and evolving standards, practices, and methods in professional mental health practice. Stigma and Health Quarterly • ISSN: 2376-6972 • www.apa.org.pubs/journals/sah Publishes original research articles that may include tests of hypotheses about the form and impact of stigma, examination of strategies to decrease stigma’s effects, and survey research capturing stigma in populations. The Humanistic Psychologist Quarterly • ISSN: 0887-3267 • www.apa.org/pubs/journals/hum NOW PUBLISHED BY APA Publishes papers on qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods research; humanistic, existential, constructivist, and transpersonal theories and psychotherapies. ONLINE ONLY Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice™ eISSN: 2372-9414 • www.apa.org/pubs/journals/bar ONLINE ONLY Behavioral Development Bulletin™ eISSN: 1942-0722 • www.apap.org/pubs/journals/bdb Motivation Science ISSN: 2333-8113 • www.apa.org/pubs/journals/mot VISIT BOOTH ONLINE ONLY #1548 AT ALA Psychology & Neuroscience MIDWINTER eISSN: 1983-3288 • www.apa.org/pubs/journals/pne Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology ISSN: 2332-2101 • www.apa.org/pubs/journals/stl Translational Issues in Psychological Science® ISSN: 2332-2136 • www.apa.org/pubs/journals/tps ALSO OF INTEREST American Psychologist® The Offi cial Journal of the American Psychological Association ISSN: 0003-066X • www.apa.org/pubs/journals/amp ALL FEES WAIVED THROUGH 2017 Archives of Scientifi c Psychology® eISSN: 2169-3269 • www.apa.org/pubs/journals/arc Enhance your psychology serials collection by adding these journals to your library.