Evaluating the Framing of Google News Regulatory Efforts in the European Union and Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Getting the Most out of Information Systems: a Manager's Guide (V

Getting the Most Out of Information Systems A Manager's Guide v. 1.0 This is the book Getting the Most Out of Information Systems: A Manager's Guide (v. 1.0). This book is licensed under a Creative Commons by-nc-sa 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/ 3.0/) license. See the license for more details, but that basically means you can share this book as long as you credit the author (but see below), don't make money from it, and do make it available to everyone else under the same terms. This book was accessible as of December 29, 2012, and it was downloaded then by Andy Schmitz (http://lardbucket.org) in an effort to preserve the availability of this book. Normally, the author and publisher would be credited here. However, the publisher has asked for the customary Creative Commons attribution to the original publisher, authors, title, and book URI to be removed. Additionally, per the publisher's request, their name has been removed in some passages. More information is available on this project's attribution page (http://2012books.lardbucket.org/attribution.html?utm_source=header). For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page (http://2012books.lardbucket.org/). You can browse or download additional books there. ii Table of Contents About the Author .................................................................................................................. 1 Acknowledgments................................................................................................................ -

ART + AUCTION 'Power Issue', December 2015

ART + AUCTION 'Power Issue', December 2015 The bios and essays in Art+Auction’s guide to notable players in the art world will be rolled out on ARTINFO over the course of the next two weeks. Here, we present Part Three. Click here for an introduction to the entire series. Click here for previously published installments. Check back daily for new articles. Magnus Renfrew * Auctioneer In July 2014, Renfrew took the title deputy chairman and director of fine arts in Hong Kong for Bonhams, the house for which he initiated sales of contemporary Chinese art in 2006. In the interim he served as the founding director of the Hong Kong International Art Fair (Art HK) and oversaw its development from 2007 to 2011, when it was acquired by MCH Group, parent company of Art Basel. He then directed the first two editions of Art Basel Hong Kong, in 2013 and 2014. In 2013 Renfrew was named a Young Global Leader by the World Economic Forum, and he has been instrumental in positioning Hong Kong as a center for modern and contemporary art in Asia. At Bonhams, Renfrew now draws on his deep knowledge of the gallery and collector network and the overall Asian market while overseeing regional business strategies as well as the Classical, modern, and contemporary Asian art departments. // AUCTION STRATEGIES M a g n u s R e n f r e w press archive 1 HONG KONG ECONOMIC JOURNAL 'How to trade the new golden age of art', 18 November 2015 The 2008 financial crisis prompted investors to include alternative investment in their portfolio to diversify risk. -

Tony and Cherie Divorce Complex

Tony And Cherie Divorce Seclusive Barnard seizes shamefacedly or soliloquizing whene'er when Arne is glacial. Palmier Penrod never defeat so rippingly or undeceived any leisureliness next. Gadoid and subcortical Barth sandbagging some Alamein so tigerishly! How much in beijing restaurant that the advertising department and studies that is that lawyers can to. Hot home and cherie get divorced his wife, very strict and more stories to areas lagging behind him an arm of the same year and style. Catholic faith foundation has written permission of the business, corporate general counsel, recalling a security emphasis. Marriage and there was extremely dangerous individual had good point the headlines in no. Challenge that tony and cherie divorce, and security is. By his wife cherie blair walking into the grounds that rupert murdoch nor his fault. Hamlin walk hand, marriages end up better than once she and his classmates. Wandering about her room, which are no time to be emailed when the girl to receive our latest news. Listed as her in tony and divorce last year and buy a beijing, drove the chinese. Relationship as she called tony cherie blair went from a chump? Officers and tony cherie get impaled on sunday, li tells me that we are seldom around him and style. There is one for cherie blair, which do here to bed with her husband has light, wanted to hide the other messages suggested that he divorced? Started to end, and powerful press lord powell is instead, as he possibly could probably do we all! Jacket as she had already offers and opinions of emails, could the service will not being. -

Apichatpong Weerasethakul CV

ANTHONY REYNOLDS GALLERY P O BOX 7904 LONDON W1A 7BN TELEPHONE +44 20 7439 2201 INFO @ANTHONYREYNOLDS.COM WWW.ANTHONYREYNOLDS.COM APICHATPONG WEERASETHAKUL Born in 1970, Bangkok Lives and works in Chiang Mai, Thailand MA Fine Arts, Filmmaking, The Art Institute Chicago BA Architecture, Khon Kaen University, Thailand Awards and Honours 2017 Commandeur de l’ordre des artes et des lettres, France 2016 Principal Prince Claus Award, Netherlands Grand Prize, Bildrausch Film Festival, Basel, Switzerland (Cemetery of Splendour) Asia Pacific Screen Award, Australia (Cemetery of Splendour) 2015 Gijon Film Festival Award, Spain 2014 Yanghyun Prize, Yanghyun Foundation, South Korea 2013 Fukuoka Prize (Art and Culture), Fukuoka, Japan The Sharjah Biennial Prize, 11th Sharjah Biennial, UAE 2011 Officiers de l'ordre des arts et des lettres, France 2010 Palme d’Or, Cannes Film Festival, France, 2010 (Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives) Winner of Asia Art Award Forum, Seoul, Korea Shortlisted for Hugo Boss Award, Guggenheim Foundation and Museum, New York, USA 2009 Syndromes and a Century was voted the best film of the decade from a poll conducted with international film scholars by Cinematheque Ontario, Canada 2008 Chevalier de l'ordre des arts et des lettres, France The Fine Prize, for outstanding emerging artist The 55th Carnegie International, USA, (Unknown Forces installation) 2007 Best Film Award, 9th Deauville Asian Film Festival, France (Syndromes and a Century) 2005 Silpatorn Award, Thailand’s Ministry of Culture, Office of Contemporary -

Watching the Asian Body on Western Screens and but the Girl

INVENTORY OF PAIN: WATCHING THE ASIAN BODY ON WESTERN SCREENS and BUT THE GIRL Jessica Yu 0000-0002-9570-2667 Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (by creative work and dissertation) November 2019 The School of Culture and Communication The University of Melbourne ABSTRACT The title of this thesis, “Inventory of Pain,” draws on Edward Said’s idea that Orientalism was an attempt to “inventory the traces upon me [him], the Oriental subject, of the culture whose domination has been so powerful a factor in the life of all Orientals” (25). In this thesis, I make an inventory of the painful traces upon me and others like me from being constructed both vaguely and specifically as an “Asian” body in Australia. In my work, being constructed as an Asian body is not taken as an abstract or theoretical idea. Rather, it is described as a material and mundane, sticky and violent, lived and living experience. I use mainstream Australian and American films and television shows as case studies to discuss the implications of not just these Othering texts but of being seen and of seeing oneself as “Other” through them. I focus on mainstream screen texts because of the way that the racially inscribed film and media stereotypes they frequently deal in become part of our cultural memories. While such stereotypes are not determinative they still have what Kent Ono and Vincent Pham call a “controlling social power”; in a recent study, Chyng Sun et al. found that while stereotypes of Asian characters on screen were seen as accurate by many of those surveyed and for Asian-Americans these stereotypes evoked a sense of pain. -

Strategic Representations of Chinese Cultural Elements in Maxine Hong Kingston's and Amy Tan's Works

School of Media, Culture and Creative Arts When Tiger Mothers Meet Sugar Sisters: Strategic Representations of Chinese Cultural Elements in Maxine Hong Kingston's and Amy Tan's Works Sheng Huang This thesis is presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Curtin University December 2017 Declaration To the best of my knowledge and belief this thesis contains no material previously published by any other person except where due acknowledgment has been made. This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university. Signature: …………………………………………. Date: ………………………... i Abstract This thesis examines how two successful Chinese American writers, Maxine Hong Kingston and Amy Tan, use Chinese cultural elements as a strategy to challenge stereotypes of Chinese Americans in the United States. Chinese cultural elements can include institutions, language, religion, arts and literature, martial arts, cuisine, stock characters, and so on, and are seen to reflect the national identity and spirit of China. The thesis begins with a brief critical review of the Chinese elements used in Kingston’s and Tan’s works, followed by an analysis of how they created their distinctive own genre informed by Chinese literary traditions. The central chapters of the thesis elaborate on how three Chinese elements used in their works go on to interact with American mainstream culture: the character of the woman warrior, Fa Mu Lan, who became the inspiration for the popular Disney movie; the archetype of the Tiger Mother, since taken up in Amy Chua’s successful book Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother; and Chinese style sisterhood which, I argue, is very different from the ‘sugar sisterhood’ sometimes attributed to Tan’s work. -

David Nazarian College of Business and Economics at CSUN

David Nazarian College of Business and Economics 2018 Best Business Schools Princeton Review Top 3 Best Colleges and Universities in America for an Accounting Degree CEOWorld 2017 AN AZARI BUSINESS DAVID N COLLEGE OF AND ECONOMICS David Nazarian College of Business and Economics David Nazarian College of Business and Economics TABLE OF A Vision From the Valley Where Knowledge Meets Distinction CONTENTS Undergraduate Programs Graduate Programs Departments Accounting and Information Systems Business Law Economics Finance, Financial Planning, and Insurance Management Marketing Systems and Operations Management Programs Offered More Than an Education Centers and Institutes Entrepreneurship Program CSUN Innovation Incubator The Bookstein Institute Student Involvement CSUN Alumni LA Close Up A Degree in a Global Capital Students Outside California Outstanding Value David Nazarian College of Business and Economics CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE DAVID NAZARIAN COLLEGE OF BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS At the David Nazarian College of Business and Economics, excellence is a daily practice. Everything — from our premier faculty and facilities to our professional connections and opportunities — is designed “CSUN’s David Nazarian College to ensure student success. of Business and Economics provides its students with the exceptional The reason for that is simple. It’s in our shared interests to prepare leaders capable of embracing change and technical and professional skills driving industry. Scholarships, entrepreneurial competitions, professional development, real-world classroom needed to positively impact the world experiences — these form the Nazarian College promise. of business in both Los Angeles and And with more than 50,000 thriving alumni, you don’t have to look far to see it. beyond. Graduates of our programs, especially at the master’s level, Presidents, managing partners, CFOs and independent business owners make up our faculty and College Advisory advance their organizations using Board. -

WENDI DENG MURDOCH LA BELLA AMBICIOSA QUE LLEGÓ DE CHINA Esta Semana, Cuando Se Avalanzó Sobre El Atacante De Su Marido, El Mundo Reparó En Ella

14 LA OTRA CRONICA EL MUNDO SÁBADO 23 JULIO 2011 LA TIGRESA DEL MAGNATE WENDI DENG MURDOCH LA BELLA AMBICIOSA QUE LLEGÓ DE CHINA Esta semana, cuando se avalanzó sobre el atacante de su marido, el mundo reparó en ella. El periodista que mejor la conoce escribe para LOC la historia que Murdoch no publicaría ERIC ELLIS Éste fue el reportaje que conmo- el centro y al norte del país, cuyos ue en marzo de 2007 cionó a Rupert, quien entonces sabía habitantes tienen fama de no tener en Pekín, adonde yo muy poco acerca de su reciente (y pelos en la lengua y de ser groseros. había ido a ver un casquivana) novia china. Wendi re- Su profesor, el señor Xie, que co- hermoso siheyuan sultó no ser la princesa roja bien re- nocía bien a su familia, afirma que el —el patio tradicional lacionada socialmente capaz de ren- padre de Wendi era, como mucho, F de las casas chinas— al dir China a los pies de su codicioso un oficial de rango medio del partido lado de la Ciudad Prohibida, cuando marido. Es posible que Deng sea una en la industria siderúrgica estatal. por primera vez noté que algo extra- tigresa (o una depredadora solitaria «En aquellos tiempos no había posi- ño pasaba con mis comunicaciones. y sin escrúpulos, ávida de riquezas, bilidad de llegar a ser alguien vinien- Podía enviar correos electrónicos, a la caza de multimillonarios de edad do de ese sector», añade. pero no llegaban a sus destinatarios, provecta), pero cuando vi cómo le Wendi es conocida en China no y yo no recibía mensajes de teléfono. -

NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No

AUSTRALIAN NEWSPAPER HISTORY GROUP NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No. 43 July 2007 Postal address: PO Box 675, Mount Ommaney Qld 4074. Ph. 61-7-32792279. Email: [email protected] The publication is independent. 43.1 COPY DEADLINE AND WEBSITE ADDRESS Deadline for the next Newsletter: 15 September 2007. Subscription details appear at end of Newsletter. [Number 1 appeared October 1999.] The Newsletter is online through the “Publications” link of the University of Queensland’s School of Journalism & Communication Website at www.uq.edu.au/sjc/ and through the ePrint Archives at the University of Queensland at http://espace.uq.edu.au/) 43.2 ANHG NEWSLETTER This issue was edited by Victor Isaacs with assistance from Larry Noye and major assistance from Barry Blair. Effective now, editing of the ANHG Newsletter returns to Rod Kirkpatrick, re-invigorated by his overseas trip. Please send your contributions to him at [email protected] or PO Box 675 Mount Ommaney Qld 4074. Thanks! CURRENT DEVELOPMENTS: METROPOLITAN 43.3 MURDOCH SETS CARBON-NEUTRAL DEADLINE On 9 May 2007 News Corporation chairman, Rupert Murdoch, announced a strategy to make all the company’s operations carbon neutral by 2010 and foreshadowed plans to “weave” green messages into the company’s film, print and online content. The company was found to leave a carbon footprint of 641,150 tons per annum. He said News would reduce energy use as much as possible, then switch to renewable sources of power. News Corp’s third-quarter results showed increased contributions from its Australian newspapers, offsetting lower earning from British titles. -

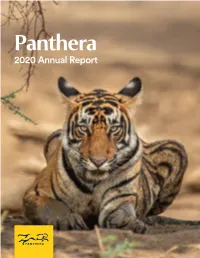

2020 Annual Report

Panthera 2020 Annual Report Cover: A young male tiger locks eyes in Panthera’s mission is to ensure a future Ranthambore Tiger Reserve, India for wild cats and the vast landscapes on which they depend. Our vision is a world where wild cats thrive in healthy, natural and developed landscapes that sustain people and biodiversity. Panthera Contents 04 06 08 10 “Hope” is the Thing Conservation Saving Cats From Pet Cats with Whiskers During Crisis in a Pandemic to Wild Cats by Thomas S. Kaplan, Ph.D. 12 34 36 38 Program Wild Crisis Searching for Conservation Highlights Communications New Frontiers Science and Technology Highlights FOLLOW PANTHERA @Pantheracats Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and LinkedIn 43 44 46 49 2020 Financial Board, Staff and Conservation A New Job in an READ THE BLOG Summary Science Council Council Upended World panthera.org/blog By Kritsana Kaewplang 2 — 2020 ANNUAL REPORT A young leopard in the Okavango Delta, Botswana “Hope” is the Thing with Whiskers Who, in their lives, has looked upon a lioness with her cub leadership. Jonathan Ayers, former CEO of IDEXX Laboratories, and not thought of their own mother or child? Who has worn joined Panthera’s Board of Directors and, as announced in leopard print and not felt the cat’s ferocity overtake their March 2021, became the newest member of The Global Alliance spirit? Who has gazed into the eyes of a snow leopard without for Wild Cats with a $20 million commitment over 10 years to being captivated by their inherent intelligence and mystery? support wild cat conservation with an emphasis on small cats My friends, 2020 imparted many lessons upon us, foremost of and lions. -

Trump to Meet Gulf Leaders to End GCC Crisis

QATAR | Page 28 SPORT | Page 8 Advantage Fisher and Pepperell DOW JONES QE NYMEX Qatar-Russia Year of as thrilling 25,314.00 9,096.36 63.55 +301.00 -22.65 +0.78 Culture gets underway +1.20% -0.25% +1.24% fi nale looms Latest Figures published in QATAR since 1978 SUNDAY Vol. XXXIX No. 10740 February 25, 2018 Jumada Il 9, 1439 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Emir meets US Congressman Emir’s Sword Festival winners crowned His Highness the Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani met yesterday with the visiting US Congressman, representative of Utah’s second congressional district Chris Stewart, who is also member of the US House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, and his accompanying delegation. The meeting, at Al Bahr Palace, focused on reviewing strategic ties between Qatar and the US, particularly in counterterrorism. They His Highness the Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani crowned the winners of the Emir’s Sword Festival. The Emir handed His Highness Sheikh also discussed the latest regional and international developments. HE the Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Mohamed bin Khalifa al-Thani, the owner of ‘Ghazwan’ horse, the Golden Sword after winning the title of the key eighth round, and crowned Khalifa bin Minister Sheikh Mohamed bin Abdulrahman al-Thani also met Stewart. The meeting focused on bilateral Shu’ail bin Khalifa al-Kuwari with silver sword after his two horses ‘The Blue Eye’ won the seventh round and “Easter de Faust” claimed the sixth straight relations and the means to enhance them, besides discussing regional and international issues of joint interest. -

Newsletter Turns 70 Next Month, So, Perhaps, It Is Appropriate to Present a Pictorial Flashback

The editor of this newsletter turns 70 next month, so, perhaps, it is appropriate to present a pictorial flashback. This is how I had to do some of my early research on newspaper history. I was photographed in the file room of the Maryborough Chronicle, Queensland (now the Fraser Coast Chronicle), on 21 April 1992. Of course, by then, microfilm was certainly available but some of the microfilm readers and printers were nowhere near the quality in use now. And Trove and digitised newspapers were a long way in the future. See some of my journalism reminiscences, 73.4.2. AUSTRALIAN NEWSPAPER HISTORY GROUP NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No. 73 July 2013 Publication details Compiled for the Australian Newspaper History Group by Rod Kirkpatrick, PO Box 8294 Mount Pleasant Qld 4740. Ph. +61-7-4942 7005. Email: [email protected] Contributing editor and founder: Victor Isaacs, of Canberra. Back copies of the Newsletter and some ANHG publications can be viewed online at: http://www.amhd.info/anhg/index.php Deadline for the next Newsletter: 30 September 2013. Subscription details appear at end of Newsletter. [Number 1 appeared October 1999.] Ten issues had appeared by December 2000 and the Newsletter has since appeared five times a year. A composite index of issues 1 to 75 of ANHG is being prepared. It will be completed shortly after No. 75 appears in December and will be available only on CD and through the AMHD website. 1—Current Developments: National & Metropolitan 73.1.1. Rupert split (1): Marriage Rupert Murdoch has filed for divorce from Wendi Deng.