Branding As an Antidote to Indecency Regulation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cinema Recognizing Making Intimacy Vincent Tajiri Even Hotter!

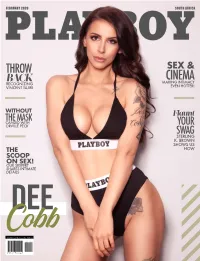

FEBRUARY 2020 SOUTH AFRICA THROW SEX & BACK CINEMA RECOGNIZING MAKING INTIMACY VINCENT TAJIRI EVEN HOTTER! WITHOUT Flaunt THE MASK CANDID WITH YOUR ORVILLE PECK SWAG STERLING K. BROWN SHOWS US THE HOW SCOOP ON SEX! OUR SEXPERT SHARES INTIMATE DETAILS Dee Cobb WWW.PLAYBOY.CO.ZA R45.00 20019 9 772517 959409 EVERY. ISSUE. EVER. The complete Playboy archive Instant access to every issue, article, story, and pictorial Playboy has ever published – only on iPlayboy.com. VISIT PLAYBOY.COM/ARCHIVE SOUTH AFRICA Editor-in-Chief Dirk Steenekamp Associate Editor Jason Fleetwood Graphic Designer Koketso Moganetsi Fashion Editor Lexie Robb Grooming Editor Greg Forbes Gaming Editor Andre Coetzer Tech Editor Peter Wolff Illustrations Toon53 Productions Motoring Editor John Page Senior Photo Editor Luba V Nel ADVERTISING SALES [email protected] for more information PHONE: +27 10 006 0051 MAIL: PO Box 71450, Bryanston, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2021 Ƶč%./0(++.ǫ(+'ć+1.35/""%!.'Čƫ*.++/0.!!0Ē+1.35/ǫ+1(!2. ČĂāĊā EMAIL: [email protected] WEB: www.playboy.co.za FACEBOOK: facebook.com/playboysouthafrica TWITTER: @PlayboyMagSA INSTAGRAM: playboymagsa PLAYBOY ENTERPRISES, INTERNATIONAL Hugh M. Hefner, FOUNDER U.S. PLAYBOY ǫ!* +$*Čƫ$%!"4!10%2!þ!. ƫ++,!.!"*!.Čƫ$%!"ƫ.!0%2!þ!. Michael Phillips, SVP, Digital Products James Rickman, Executive Editor PLAYBOY INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHING !!*0!(Čƫ$%!"ƫ+))!.%(þ!.Ē! +",!.0%+*/ Hazel Thomson, Senior Director, International Licensing PLAYBOY South Africa is published by DHS Media House in South Africa for South Africa. Material in this publication, including text and images, is protected by copyright. It may not be copied, reproduced, republished, posted, broadcast, or transmitted in any way without written consent of DHS Media House. -

Brief of Petitioner for FCC V. Fox Television Stations, 07-582

No. 07-582 In the Supreme Court of the United States ________________ FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION AND UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Petitioners, v. FOX TELEVISION STATIONS, INC., ET AL., Respondents. _________________ On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit _________________ AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF OF NATIONAL RELIGIOUS BROADCASTERS IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS ___________________ Craig L. Parshall Joseph C. Chautin III Counsel of Record Elise M. Stubbe General Counsel Mark A. Balkin National Religious Co-Counsel Broadcasters Hardy, Carey, Chautin 9510 Technology Dr. & Balkin, LLP Manassas, VA 20110 1080 West Causeway 703-331-4517 Approach Mandeville, LA 70471 985-629-0777 QUESTION PRESENTED FOR REVIEW Amicus adopts the question presented as presented by Petitioner. The question presented for review is as follows: Whether the court of appeals erred in striking down the Federal Communications Commission’s determination that the broadcast of vulgar expletives may violate federal restrictions on the broadcast of “any obscene, indecent, or profane language,” 18 U.S.C. § 1464, see 47 C.F.R. § 73.3999, when the expletives are not repeated. i TABLE OF CONTENTS QUESTION PRESENTED FOR REVIEW .................i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .......................................v INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE ............................x STATEMENT OF THE CASE .................................xii SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ..................................xii ARGUMENT ..............................................................1 I. THE FCC’S REASONS FOR ADJUSTING ITS INDECENCY POLICY WERE RATIONAL AND REASONABLE .....................1 A. The Court of Appeals Failed to Give the Required Deference and Latitude to the FCC ..................................................1 B. The FCC Gave Sufficient and Adequate Reasoning Why its Prior Indecency Policy Regarding Fleeting Expletives was Unworkable and Required Adjustment .................................3 1. -

FCC-06-11A1.Pdf

Federal Communications Commission FCC 06-11 Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Annual Assessment of the Status of Competition ) MB Docket No. 05-255 in the Market for the Delivery of Video ) Programming ) TWELFTH ANNUAL REPORT Adopted: February 10, 2006 Released: March 3, 2006 Comment Date: April 3, 2006 Reply Comment Date: April 18, 2006 By the Commission: Chairman Martin, Commissioners Copps, Adelstein, and Tate issuing separate statements. TABLE OF CONTENTS Heading Paragraph # I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................. 1 A. Scope of this Report......................................................................................................................... 2 B. Summary.......................................................................................................................................... 4 1. The Current State of Competition: 2005 ................................................................................... 4 2. General Findings ....................................................................................................................... 6 3. Specific Findings....................................................................................................................... 8 II. COMPETITORS IN THE MARKET FOR THE DELIVERY OF VIDEO PROGRAMMING ......... 27 A. Cable Television Service .............................................................................................................. -

Initial Interest Confusion

INITIAL INTEREST CONFUSION Excerpted from Chapter 7 (Rights in Internet Domain Names) of E-Commerce and Internet Law: A Legal Treatise With Forms, Second Edition, a 4-volume legal treatise by Ian C. Ballon (Thomson/West Publishing 2014) LAIPLA SPRING SEMINAR OJAI VALLEY INN OJAI, CA JUNE 6-8, 2014 Ian C. Ballon Greenberg Traurig, LLP Los Angeles: Silicon Valley: 1840 Century Park East, Ste. 1900 1900 University Avenue, 5th Fl. Los Angeles, CA 90067 East Palo Alto, CA 914303 Direct Dial: (310) 586-6575 Direct Dial: (650) 289-7881 Direct Fax: (310) 586-0575 Direct Fax: (650) 462-7881 [email protected] <www.ianballon.net> Google+, LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook: IanBallon This paper has been excerpted from E-Commerce and Internet Law: Treatise with Forms 2d Edition (Thomson West 2014 Annual Update), a 4-volume legal treatise by Ian C. Ballon, published by West LegalWorks Publishing, 395 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014, (212) 337-8443, www.ianballon.net. Ian C. Ballon Los Angeles 1840 Century Park East Shareholder Los Angeles, CA 90067 Internet, Intellectual Property & Technology Litigation T 310.586.6575 F 310.586.0575 Admitted: California, District of Columbia and Maryland Silicon Valley JD, LLM, CIPP 1900 University Avenue 5th Floor [email protected] East Palo Alto, CA 94303 Google+, LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook: Ian Ballon T 650.289.7881 F 650.462.7881 Ian Ballon represents Internet, technology, and entertainment companies in copyright, intellectual property and Internet litigation, including the defense of privacy and behavioral advertising class action suits. He is also the author of the leading treatise on Internet law, E-Commerce and Internet Law: Treatise with Forms 2d edition, the 4-volume set published by West (www.IanBallon.net). -

Media Entity Fox News Channel Oct

Federal Communications Commission FCC 06-11 Programming Service Launch Ownership by Date "Other" Media Entity Fox News Channel Oct. 96 NewsCoqJ. Fox Reality May 05 News Corp. Fox Sports Net Nov. 97 News Corp. Fox Soccer Channel (fonnerly Fox Sports World) Nov. 97 News Corp. FX Jun. 94 News Corp. Fuel .luI. 03 News Corp. Frec Speech TV (FSTV) Jun. 95 Game Show Network (GSN) Dec. 94 Liberty Media Golden Eagle Broadcasting Nov. 98 preat American Country Dec. 95 EW Scripps Good Samaritan Network 2000 Guardian Television Network 1976 Hallmark Channel Sep.98 Liberty Media Hallmark Movie Channel Jan. 04 HDNET Sep.OI HDNET Movies Jan. 03 Healthy Living Channel Jan. 04 Here! TV Oct. 04 History Channel Jan. 95 Disney, NBC-Universal, Hearst History International Nov. 98 Disney, NBC-Universal, Hearst (also called History Channel International) Home & Garden Television (HGTV) Dec. 94 EW Scripps Home Shopping Network (HSN) Jul. 85 Home Preview Channel Horse Racing TV Dec. 02 !Hot Net (also called The Hot Network) Mar. 99 Hot Net Plus 2001 Hot Zone Mar. 99 Hustler TV Apr. 04 i-Independent Television (fonnerly PaxTV) Aug. 98 NBC-Universal, Paxson ImaginAsian TV Aug. 04 Inspirational Life Television (I-LIFETV) Jun. 98 Inspirational Network (INSP) Apr. 90 i Shop TV Feb. 01 JCTV Nov. 02 Trinity Broadcasting Network 126 Federal Communications Commission FCC 06-11 Programming Service Launch Ownership by Date "Other" Media EntIty ~ewelry Television Oct. 93 KTV ~ Kids and Teens Television Dominion Video Satellite Liberty Channel Sep. 01 Lifetime Movie Network .luI. 98 Disney, Hearst Lifetime Real Women Aug. -

Fairweather and Rogerson: Politics and Society After De-Massification of the Media

Info, Comm & Ethics in Society (2005) 3: 159-166 © 2005 Troubador Publishing Ltd. EDITORIAL Politics and Society after De-Massification of the Media N Ben Fairweather and Simon Rogerson Centre for Computing and Social Responsibility, De Montfort University, Leicester, UK Email: [email protected] As Information and Communications Technologies (ICTs) develop and are more widely adopted, news and current affairs media are moving away from being mass-media, with increasing audience fragmentation, and media targeting specific niche audiences. Patterns of opinion formation are changing with these changes. Broadcast mass-media had the potential to moderate the intensity of political disputes in a way which is being threatened by these changes. There is a danger that there will be a diminishing of the effectiveness of any remaining public space in which opposing views can be fully and fairly aired, and some balanced view of what is happening, and has happened, can be formed. If such a public space ceases to exist or ceases to be effective, key elements to the democratic process may be under severe threat in some polities. Keywords: Narrowcasting, Cleavage, Current Affairs, Audience Fragmentation, Opinion Formation INTRODUCTION al. 2002, 285). This editorial seeks to examine pos- sible consequences for politics and for society. For most of the last century, media have been mass- media, where the same message is broadcast to a large population, who thus to a significant extent NEWS SOURCES have a common understanding of what is happen- ing in the world around them. This has had both Professional good, and bad, effects. The age of the Internet, digital and cable televi- It has been judged that one of the hallmarks of a sion, has allowed ‘narrowcasting’ (Smith-Shomade, ‘free society’ has been the existence of varied and 2004, p70), where communication moves towards independent media sources (see, for example, being ‘many to many’, and two-way and away from Binyon, 2002, 461). -

Burkas and Bikinis: Playboy in Indonesia1

DE1- 173-I BURKAS AND BIKINIS: PLAYBOY IN INDONESIA1 Original written by professor David Bach at IE Business School. Original version, 3 June 2011. Published by IE Business Publishing, María de Molina 13, 28006 – Madrid, Spain. ©2011 IE. Total or partial publication of this document without the express, written consent of IE is prohibited. Christie Hefner was no stranger to controversy. She had the physical appearance of the All- American professional: perfectly coiffeured shiny blond hair, tasteful yet elegant outfits, and understated jewelry that nevertheless communicated both style and confidence. Anybody meeting her for the first time could have been forgiven for mistaking her for a lawyer, consultant, or the general manager of an upscale country club. Hefner was nothing of the sort for she was both a self-proclaimed feminist and the CEO of the company with the most recognizable name in men's entertainment: Playboy Enterprises. Since taking over the company from her father Hugh Hefner, the quintessential playboy, she had had to work her way out of many difficult situations, both in Playboy’s U.S. home market and overseas. But for two months, after receiving an unnerving phone call in December 2006 that Erwin Arnada, the editor-in-chief of Playboy Indonesia, had been charged and indicted for promoting obscenity, Hefner had been agonizing over possible courses of action. Her most immediate concern was for Arnada’s safety. But she also knew that the incident raised important questions beyond Arnada. In managing the situation, Hefner had to make decisions that would inevitably affect the future global strategy of Playboy Enterprises. -

Supreme Court of the United States ______FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION, Et Al., Petitioners, V

No. 10-1293 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States _________ FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION, et al., Petitioners, v. FOX TELEVISION STATIONS, INC., et al., Respondents. _________ On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit _________ BRIEF OF RESPONDENTS CENTER FOR CREATIVE VOICES IN MEDIA AND THE FUTURE OF MUSIC COALITION _________ *Andrew Jay Schwartzman Chrystiane B. Pereira Media Access Project 1625 K Street, NW Suite 1000 Washington, DC 20006 (202) 232-4300 [email protected] November 3, 2011 * Counsel of Record i QUESTION PRESENTED Whether the court of appeals properly determined that the Federal Communications Commission‘s (FCC) context-based indecency policy is unconsti- tutionally vague and accordingly unenforceable. ii CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT Pursuant to Rule 26.1 of the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure, Center for Creative Voices in Media and Future of Music Coalition (jointly ―Cen- ter‖) respectfully submit this corporate disclosure statement. The Center of Creative Voices in Media does not have a parent company and no publicly held company owns 10 percent or more of stock therein. The Future of Music Coalition does not have a parent company and no publicly held company owns 10 percent or more of stock therein. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS QUESTION PRESENTED........................................... i CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT ............ ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ....................................... iv STATEMENT .............................................................. 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ..................................... 6 ARGUMENT ............................................................... 8 I. Nothing in Pacifica Authorizes the FCC‘s New Indecency Policy ...................... 9 A. Pacifica Was A Narrow Ruling Proceeding From the Expecta- tion That The Commission Would Tread Cautiously ..................... 10 B. The FCC‘s Impermissibly Va- gue New Policy Has Had A Chilling Effect .................................... -

On Podcasting

The Transom Review Volume 8/Issue 4 Curtis Fox September 2008 (Edited by Sydney Lewis) Intro from Jay Allison As satisfying as the work can be, it's tough to make a living as an independent producer in public radio. Producers have traditionally circumvented this problem with Day Jobs, sometimes capitalizing on public radio skills. That was true with Audiobooks a while back, and it's true of Podcasts now. Curtis Fox is a Master of Podcasts, and in his Transom Manifesto, he tells you how he ended up where he is. He'll also tell you about the implications of podcasting's rise on the public radio talent pool. And you can hear Curtis' recent taped presentation at the PRPD. And ask him questions. About Curtis Fox Curtis Fox runs a small podcast production company whose main clients are The Poetry Foundation, The New Yorker, and Parents Magazine. He comes out of public radio, where he contributed to many shows, including All Things Considered, Studio 360 and On the Media. He worked on staff for a now defunct show called The Next Big Thing, producing radio drama, cultural journalism, interviews and personal essays. He lives in Brooklyn with his wife and two young daughters. Curtis Fox The Transom Review – Vol.8/ Issue 4 On Podcasting There’s something about the word “manifesto” that demands bold underlined STATEMENTS. And so I will conform my (modest) message to the medium. PUBLIC RADIO ISN’T THE ONLY PLACE FOR PUBLIC RADIO PRODUCERS TO WORK ANYMORE I’ve always thought of public radio as a kind of ghetto for producers (and listeners) of reasonably intelligent audio. -

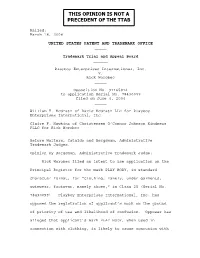

This Opinion Is Not a Precedent of the Ttab

THIS OPINION IS NOT A PRECEDENT OF THE TTAB Mailed: March 18, 2008 UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE _____ Trademark Trial and Appeal Board ______ Playboy Enterprises International, Inc. v. Rick Worobec _____ Opposition No. 91165814 to application Serial No. 78430099 filed on June 4, 2004 _____ William T. McGrath of Davis McGrath LLC for Playboy Enterprises International, Inc. Claire F. Hawkins of Christensen O’Connor Johnson Kindness PLLC for Rick Worobec ______ Before Walters, Cataldo and Bergsman, Administrative Trademark Judges. Opinion by Bergsman, Administrative Trademark Judge: Rick Worobec filed an intent to use application on the Principal Register for the mark PLAY BODY, in standard character format, for “clothing, namely, under garments, swimwear; footwear, namely shoes,” in Class 25 (Serial No. 78430099). Playboy Enterprises International, Inc. has opposed the registration of applicant’s mark on the ground of priority of use and likelihood of confusion. Opposer has alleged that applicant’s mark PLAY BODY, when used in connection with clothing, is likely to cause confusion with Opposition No. 91165814 opposer’s famous PLAYBOY trademarks, used in connection with a wide variety of goods and services, including clothing.1 Applicant denied the salient allegations in the notice of opposition. The Record By operation of Trademark Rule 2.122, 37 CFR §2.122, the record includes the pleadings and the application file for applicant’s mark. The record also includes the following testimony and evidence: A. Opposer’s evidence. 1. Notice of reliance on a certified copy, showing the current status and ownership in opposer, of Registration No. 3140250 for the mark PLAYBOY, in standard character form, for lingerie, sleepwear, loungewear, wraps, and robes;2 2. -

Building a Better Mousetrap: Patenting

631 RICHARD & WEINERT 2/28/2013 3:57 PM PUNTING IN THE FIRST AMENDMENT‘S RED ZONE: THE SUPREME COURT‘S ―INDECISION‖ ON THE FCC‘S INDECENCY REGULATIONS LEAVES BROADCASTERS STILL SEARCHING FOR ANSWERS Robert D. Richards* & David J. Weinert** I. INTRODUCTION Just one week before rendering its controversial landmark decision on the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act1— arguably the most anticipated ruling of the October 2011 Term—the U.S. Supreme Court sidestepped the longstanding question of whether the First Amendment, given today‘s multifaceted media landscape, no longer permits the Federal Communications Commission to regulate broadcast indecency on the nation‘s airwaves. The Court‘s narrow ruling in FCC v. Fox Television Stations, Inc.2 (―Fox II‖) let broadcasters off the hook for the specific on-air transgressions that brought the case to the Court‘s docket— twice3—but did little to resolve the larger looming issue of whether such content regulations have become obsolete. Justice Anthony Kennedy, writing for a unanimous Court, instead concluded that ―[t]he Commission failed to give Fox or ABC fair notice prior to the broadcasts in question that fleeting expletives and momentary nudity could be found actionably indecent.‖4 As a result of this lack of notice, ―the Commission‘s standards as applied * John & Ann Curley Professor of First Amendment Studies and Founding Director of the Pennsylvania Center for the First Amendment at The Pennsylvania State University. Member of the Pennsylvania Bar. ** Lecturer, Communication Arts & Sciences and Ph.D. candidate, Mass Communications, The Pennsylvania State University. 1 See Nat‘l Fed‘n of Indep. -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School Donald P

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School Donald P. Bellisario College of Communications BROADCASTING, THE FCC, AND PROGRAMMING REGULATION: A NEW DIRECTION IN INDECENCY ENFORCEMENT A Dissertation in Mass Communications by David J. Weinert Ó 2018 David J. Weinert Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2018 The dissertation of David J. Weinert was reviewed and approved* by the following: Robert D. Richards John and Ann Curley Distinguished Professor of First Amendment Studies Dissertation Advisor and Chair of Committee Robert M. Frieden Pioneer Chair and Professor of Telecommunications and Law Matthew S. Jackson Head, Department of Telecommunications and Associate Professor Thomas M. Place Professor of Law, The Dickinson School of Law at Penn State Matthew P. McAllister Chair of Graduate Programs and Professor *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ABSTRACT The U.S. Supreme Court, in June 2012, left broadcasters in a “holding pattern” by dodging the longstanding question of whether the Federal Communications Commission’s broadcast indecency policy can survive constitutional scrutiny today given the vastly changed media landscape. The high court’s narrow ruling in FCC v. Fox Television Stations, Inc. exonerated broadcasters for the specific on-air improprieties that brought the case to its attention, but did little to resolve the larger and more salient issue of whether such content regulations have become archaic. As a result, the Commission continues to police the broadcast airwaves, recently sanctioning a Roanoke, Virginia television station $325,000 for alleged broadcast indecency. This dissertation yields an in-depth analysis and synthesis of the legal obstacles the FCC will encounter in attempting to establish any revamped policy governing broadcast indecency.