Undercurrents Sexuality Studies Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COI MTR-HH Day40 14Jan2019

Commission of Inquiry into the Diaphragm Wall and Platform Slab Construction Works at the Hung Hom Station Extension under the Shatin to Central Link Project Day 40 Page 1 Page 3 1 Monday, 14 January 2019 1 COMMISSIONER HANSFORD: And maybe if we could look it -- 2 (10.02 am) 2 I don't know, something like 25 January; bring it as 3 MR PENNICOTT: Good morning, sir. 3 up-to-date as we possibly can. 4 CHAIRMAN: Good morning. 4 MR BOULDING: It may well even be the case that we could 5 MR PENNICOTT: Sir, you will see around the room this 5 take it up to 29 January. We will see what can be done 6 morning that there are some perhaps unfamiliar faces to 6 and we will update it as much as we possibly can. 7 you. That is because we are starting the structural 7 COMMISSIONER HANSFORD: Thank you very much. 8 engineering expert evidence this morning, and I think, 8 CHAIRMAN: Good. 9 although I haven't counted, that most if not all of the 9 MR PENNICOTT: Sir, before we get to Prof Au -- good 10 structural engineering experts are in the room. 10 morning; we'll be with you shortly, Prof Au -- could 11 CHAIRMAN: Yes. 11 I just mention this. I think it's a matter that has 12 MR PENNICOTT: As you know, Prof McQuillan is sat next to 12 been drawn to the Commission's attention, but there have 13 me, I can see Mr Southward is there, and I think 13 been some enquiries from the media, and in particular 14 Dr Glover is at the back as well, and at the moment 14 the Apple Daily, in relation to questions concerning the 15 Prof Au is in the witness box. -

Public Museums and Film Archive Under Management of Leisure and Cultural Services Department (In Sequence of Opening)

Appendix 1 Public Museums and Film Archive Under Management of Leisure and Cultural Services Department (in sequence of opening) Museum Year Location Opening Hours (Note 2) opened 1. Lei Cheng Uk Han 1957 41 Tonkin Street, Sham Shui Po, 10 am to 6 pm Tomb Museum Kowloon Closed on Thursday 2. Hong Kong Space 1980 10 Salisbury Road, Tsim Sha 1 pm to 9 pm for Museum Tsui, Kowloon week days 10 am to 9 pm for week ends and public holiday Closed on Tuesday 3. Sheung Yiu Folk 1984 Pak Tam Chung Nature Trail, 9 am to 4 pm Museum Sai Kung, New Territories Closed on Tuesday 4. Flagstaff House 1984 10 Cotton Tree Drive, Central, 10 am to 5 pm Museum of Tea Ware Hong Kong (inside Hong Kong Closed on Tuesday Park) 5. Hong Kong Railway 1985 13 Shung Tak Street, Tai Po 9 am to 5 pm Museum Market, Tai Po, New Territories Closed on Tuesday 6. Sam Tung Uk 1987 2 Kwu Uk Lane, Tsuen Wan, 9 am to 5 pm Museum New Territories Closed on Tuesday 7. Law Uk Folk Museum 1990 14 Kut Shing Street, Chai Wan, 10 am to 6 am Hong Kong Closed on Thursday 8. Hong Kong Museum 1991 10 Salisbury Road, Tsim Sha 10 am to 6 pm of Art (Note 1) Tsui, Kowloon Closed on Thursday 9. Hong Kong Science 1991 2 Science Museum Road, Tsim 1 pm to 9 pm for Museum Sha Tsui East, Kowloon week days 10 am to 9 pm for week ends and public holiday Closed on Thursday 10. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Queerness and Chinese Modernity: the Politics of Reading Between East and East a Dissertati

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Queerness and Chinese Modernity: The Politics of Reading Between East and East A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Literature by Alvin Ka Hin Wong Committee in Charge: Professor Yingjin Zhang, Co-Chair Professor Lisa Lowe, Co-Chair Professor Patrick Anderson Professor Rosemary Marangoly George Professor Larissa N. Heinrich 2012 Copyright Alvin Ka Hin Wong, 2012 All rights reserved. The dissertation of Alvin Ka Hin Wong is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair ________________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2012 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page …………………………………………………….……………….….…iii Table of Contents ………………………………………………………………..…….…iv List of Illustrations ……………………………………………………………….…........v Acknowledgments …………………………………………………………………….....vi Vita …………………………………………………….…………………………….…...x Abstract of the Dissertation ………………………………………………….……….….xi INTRODUCTION.……………………………………………………………….……....1 CHAPTER ONE. Queering Chineseness and Kinship: Strategies of Rewriting by Chen Ran, Chen Xue and Huang Biyun………………………….………...33 -

The New Hong Kong Cinema and the "Déjà Disparu" Author(S): Ackbar Abbas Source: Discourse, Vol

The New Hong Kong Cinema and the "Déjà Disparu" Author(s): Ackbar Abbas Source: Discourse, Vol. 16, No. 3 (Spring 1994), pp. 65-77 Published by: Wayne State University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41389334 Accessed: 22-12-2015 11:50 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wayne State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Discourse. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 142.157.160.248 on Tue, 22 Dec 2015 11:50:37 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions The New Hong Kong Cinema and the Déjà Disparu Ackbar Abbas I For about a decade now, it has become increasinglyapparent that a new Hong Kong cinema has been emerging.It is both a popular cinema and a cinema of auteurs,with directors like Ann Hui, Tsui Hark, Allen Fong, John Woo, Stanley Kwan, and Wong Rar-wei gaining not only local acclaim but a certain measure of interna- tional recognitionas well in the formof awards at international filmfestivals. The emergence of this new cinema can be roughly dated; twodates are significant,though in verydifferent ways. -

Cheung, Leslie (1956-2003) by Linda Rapp

Cheung, Leslie (1956-2003) by Linda Rapp Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2003, glbtq, inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Leslie Cheung first gained legions of fans in Asia as a pop singer. He went on to a successful career as an actor, appearing in sixty films, including the award-winning Farewell My Concubine. Androgynously handsome, he sometimes played sexually ambiguous characters, as well as romantic leads in both gay- and heterosexually-themed films. Leslie Cheung, born Cheung Kwok-wing on September 12, 1956, was the tenth and youngest child of a Hong Kong tailor whose clients included Alfred Hitchcock and William Holden. At the age of twelve Cheung was sent to boarding school in England. While there he adopted the English name Leslie, in part because he admired Leslie Howard and Gone with the Wind, but also because the name is "very unisex." Cheung studied textiles at Leeds University, but when he returned to Hong Kong, he did not go into his father's profession. He entered a music talent contest on a Hong Kong television station and took second prize with his rendition of Don McLean's American Pie. His appearance in the contest led to acting roles in soap operas and drama series, and also launched his singing career. After issuing two poorly received albums, Day Dreamin' (1977) and Lover's Arrow (1979), Cheung hit it big with The Wind Blows On (1983), which was a bestseller in Asia and established him as a rising star in the "Cantopop" style. He would eventually make over twenty albums in Cantonese and Mandarin. -

Zz027 Bd 45 Stanley Kwan 001-124 AK2.Indd

Statt eines Vorworts – eine Einordnung. Stanley Kwan und das Hongkong-Kino Wenn wir vom Hongkong-Kino sprechen, dann haben wir bestimmte Bilder im Kopf: auf der einen Seite Jacky Chan, Bruce Lee und John Woo, einsame Detektive im Kampf gegen das Böse, viel Filmblut und die Skyline der rasantesten Stadt des Universums im Hintergrund. Dem ge- genüber stehen die ruhigen Zeitlupenfahrten eines Wong Kar-wai, der, um es mit Gilles Deleuze zu sagen, seine Filme nicht mehr als Bewe- gungs-Bild, sondern als Zeit-Bild inszeniert: Ebenso träge wie präzise erfährt und erschwenkt und ertastet die Kamera Hotelzimmer, Leucht- reklamen, Jukeboxen und Kioske. Er dehnt Raum und Zeit, Aktion in- teressiert ihn nicht sonderlich, eher das Atmosphärische. Wong Kar-wai gehört zu einer Gruppe von Regisseuren, die zur New Wave oder auch Second Wave des Hongkong-Kinos zu zählen sind. Ihr gehören auch Stanley Kwan, Fruit Chan, Ann Hui, Patrick Tam und Tsui Hark an, deren Filme auf internationalen Festivals laufen und liefen. Im Westen sind ihre Filme in der Literatur kaum rezipiert worden – und das will der vorliegende Band ändern. Neben Wong Kar-wai ist Stanley Kwan einer der wichtigsten Vertreter der New Wave, jener Nouvelle Vague des Hongkong-Kinos, die ihren künstlerischen und politischen Anspruch aus den Wirren der 1980er und 1990er Jahre zieht, als klar wurde, dass die Kronkolonie im Jahr 1997 von Großbritannien an die Volksrepublik China zurückgehen würde. Beschäftigen wir uns deshalb kurz mit der historischen Dimension. China hatte den Status der Kolonie nie akzeptiert, sprach von Hong- kong immer als unter »britischer Verwaltung« stehend. -

1 Comrade China on the Big Screen

COMRADE CHINA ON THE BIG SCREEN: CHINESE CULTURE, HOMOSEXUAL IDENTITY, AND HOMOSEXUAL FILMS IN MAINLAND CHINA By XINGYI TANG A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN MASS COMMUNICATION UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Xingyi Tang 2 To my beloved parents and friends 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First of all, I would like to thank some of my friends, for their life experiences have inspired me on studying this particular issue of homosexuality. The time I have spent with them was a special memory in my life. Secondly, I would like to express my gratitude to my chair, Dr. Churchill Roberts, who has been such a patient and supportive advisor all through the process of my thesis writing. Without his encouragement and understanding on my choice of topic, his insightful advices and modifications on the structure and arrangement, I would not have completed the thesis. Also, I want to thank my committee members, Dr. Lisa Duke, Dr. Michael Leslie, and Dr. Lu Zheng. Dr. Duke has given me helpful instructions on qualitative methods, and intrigued my interests in qualitative research. Dr. Leslie, as my first advisor, has led me into the field of intercultural communication, and gave me suggestions when I came across difficulties in cultural area. Dr. Lu Zheng is a great help for my defense preparation, and without her support and cooperation I may not be able to finish my defense on time. Last but not least, I dedicate my sincere gratitude and love to my parents. -

District : Kowloon City

District : Yau Tsim Mong Provisional District Council Constituency Areas +/- % of Population Estimated Quota Code Proposed Name Boundary Description Major Estates/Areas Population (16,964) E01 Tsim Sha Tsui West 20,881 +23.09 N Hoi Fai Road 1. SORRENTO 2. THE ARCH NE Hoi Fai Road, Hoi Po Road, Jordan Road 3. THE CULLINAN E Jordan Road, Canton Road 4. THE HARBOURSIDE 5. THE WATERFRONT Kowloon Park Drive SE Salisbury Road, Avenue of Stars District Boundary S District Boundary SW District Boundary W District Boundary NW District Boundary E02 Jordan South 18,327 +8.03 N Jordan Road 1. CARMEN'S GARDEN 2. FORTUNE TERRACE NE Jordan Road, Cox's Road 3. HONG YUEN COURT E Cox's Road, Austin Road, Nathan Road 4. PAK ON BUILDING 5. THE VICTORIA TOWERS SE Nathan Road 6. WAI ON BUILDING S Salisbury Road SW Kowloon Park Drive W Kowloon Park Drive, Canton Road NW Canton Road, Jordan Road E 1 District : Yau Tsim Mong Provisional District Council Constituency Areas +/- % of Population Estimated Quota Code Proposed Name Boundary Description Major Estates/Areas Population (16,964) E03 Jordan West 14,818 -12.65 N West Kowloon Highway, Hoi Wang Road 1. MAN CHEONG BUILDING 2. MAN FAI BUILDING NE Hoi Wang Road, Yan Cheung Road 3. MAN KING BUILDING Kansu Street 4. MAN WAH BUILDING 5. MAN WAI BUILDING E Kansu Street, Battery Street 6. MAN YING BUILDING SE Battery Street, Jordan Road 7. MAN YIU BUILDING 8. MAN YUEN BUILDING S Jordan Road 9. WAI CHING COURT SW Jordan Road, Hoi Po Road, Seawall W Seawall NW West Kowloon Highway, Hoi Po Road Seawall E 2 District : Yau Tsim Mong Provisional District Council Constituency Areas +/- % of Population Estimated Quota Code Proposed Name Boundary Description Major Estates/Areas Population (16,964) E04 Yau Ma Tei South 19,918 +17.41 N Lai Cheung Road, Hoi Ting Road 1. -

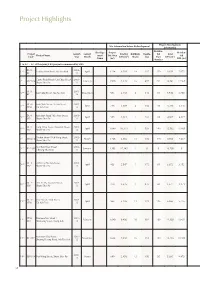

Project Highlights

Project Highlights Project Development Project Development Site Information before Redevelopment Information Information Residen- Public Develop- Project Residen- Commer- Other Project Launch Launch Existing Buildings Popula- tial Total G/IC Open Project Name ment Site Area tial cial Uses Remarks Status Code Year Month GFA (m2) Blocks tion Flats GFA (m2) GFA (m2) Space(1) Name (m2) GFA (m2) GFA (m2) GFA (m2) Number GFA (m2) 1 to 42 - 42 still ongoing URA projects commenced by URA Third round ‘Demand-led’ Scheme project DL-9: 2014- Project commencement gazetted on 11/04/14 1(3, 4) To Kwa Wan Road, Ma Tau Kok April 1,224 6,569 14 387 150 8,859 7,875 153 0 831 0 Eligible domestic owner occupiers can join the Flat for Flat KC 15 Initial acquisition offers issued on 25/06/14 scheme Castle Peak Road / Un Chau Street, 2013- Eligible domestic owner-occupiers can join the Flat for Flat 2(4) SSP-016 February 1,900 7,335 16 497 232 14,841 12,367 2,474 0 0 0 Project commencement gazetted on 21/02/14 Sham Shui Po 14 scheme Project commencement gazetted on 19/12/13 Third round ‘Demand-led’ Scheme project Initial acquisition offers issued on 04/03/14 DL-8: 2013- 3(3, 4) Kai Ming Street, Ma Tau Kok December 553 2,467 6 146 72 4,546 3,788 308 0 450 0 Eligible domestic owner occupiers can join the Flat for Flat 80% threshold for ASP reached on 10/04/14 KC 14 scheme SDEV authorised URA to proceed on 24/05/14 Land Grant application submitted on 20/06/14 Project commencement gazetted on 28/06/13 Second round ’Demand-led’ Scheme project DL-6: Fuk Chak Street -

Islands District Council Traffic and Transport Committee Paper T&TC

Islands District Council Traffic and Transport Committee Paper T&TC 41/2020 2020 Hong Kong Cyclothon 1. Objectives 1.1 The 2020 Hong Kong Cyclothon, organised by the Hong Kong Tourism Board, is scheduled to be held on 15 November 2020. This document outlines to the Islands District Council Traffic and Transport Committee the event information and traffic arrangements for 2020 Hong Kong Cyclothon, with the aim to obtain the District Council’s continuous support. 2. Event Background 2.1. Hong Kong Tourism Board (HKTB) is tasked to market and promote Hong Kong as a travel destination worldwide and to enhance visitors' experience in Hong Kong, by hosting different mega events. 2.2. The Hong Kong Cyclothon was debuted in 2015 in the theme of “Sports for All” and “Exercise for a Good Cause”. Over the past years, the event attracted more than 20,000 local and overseas cyclists to participate in various cycling programmes, as well as professional cyclists from around the world to compete in the International Criterium Race, which was sanctioned by the Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI) and The Cycling Association of Hong Kong, China Limited (CAHK). The 50km Ride is the first cycling activity which covers “Three Tunnels and Three Bridges (Tsing Ma Bridge, Ting Kau Bridge, Stonecutters Bridge, Cheung Tsing Tunnel, Nam Wan Tunnel, Eagle’s Nest Tunnel)” in the route. 2.3. Besides, all the entry fees from the CEO Charity and Celebrity Ride and Family Fun Ride and partial amount of the entry fee from other rides/ races will be donated to the beneficiaries of the event. -

Paper on the Operational Arrangements for the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge and the Hong Kong

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(4)1072/17-18(04) Ref. : CB4/PL/TP Panel on Transport Meeting on 18 May 2018 Background brief on the operational arrangements for the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge and the Hong Kong Port Purpose This paper provides background information on the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge ("HZMB") project and related Hong Kong projects. It also summarizes the major views and concerns expressed by Legislative Council ("LegCo") Members on the traffic and transport arrangements and related operational issues of HZMB upon its commissioning in past discussions. Background Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge and related Hong Kong projects 2. HZMB is a dual three-lane carriageway in the form of bridge-cum-tunnel structure sea-crossing, linking Hong Kong, Zhuhai and Macao. The project is a major cross-boundary transport infrastructure project. According to the Administration, the construction of HZMB will significantly reduce transportation costs and time for travellers and goods on roads. It has very important strategic value in terms of further enhancement of the economic development between Hong Kong, the Mainland and Macao. 3. With the connection by HZMB, the Western Pearl River Delta will fall within a reachable three-hour commuting radius of Hong Kong. The entire HZMB project consists of two parts: - 2 - (a) the HZMB Main Bridge (i.e. a 22.9 km-long bridge and 6.7 km-long subsea tunnel) situated in Mainland waters which is being taken forward by the HZMB Authority1; and (b) the link roads and boundary crossing facilities under the responsibility of the governments of Guangdong, Hong Kong and Macao ("the three governments"). -

“Current and Future Bridge Health Monitoring Systems in Hong Kong”

HIGHWAYS DEPARTMENT TSING MA CONTROL AREA DIVISION BRIDGE HEALTH SECTION “Current and Future Bridge Health Monitoring Systems in Hong Kong” by Eur Ing Dr. WONG, Kai-Yuen TMCA Division, Highways Department The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region 1 HIGHWAYS DEPARTMENT TSING MA CONTROL AREA DIVISION BRIDGE HEALTH SECTION Why Bridge Health Monitoring System is needed? • Monitoring Structural Performance and Applied Loads • Facilitating the Planning of Inspection and Maintenance • Validating Design Assumptions and Parameters • Updating and Revising Design Manuals and Standards 2 HIGHWAYS DEPARTMENT TSING MA CONTROL AREA DIVISION WASHMS BRIDGE HEALTH SECTION 1. WASHMS refers to Wind And Structural Health Monitoring System. 2. Application: “wind sensitivity structures”, i.e. frequency lower than 1 Hz. 3. Existing Bridges with WASHMS: (i) Tsing Ma & Kap Shui Mun Bridges - LFC-WASHMS. (ii) Ting Kau Bridge - TKB-WASHMS. 4. Future Bridges with WASHMS: (i) The Cable-Stayed Bridge (Hong Kong Side) in Shenzhen Western Corridor - SWC-WASHMS. (ii) Stonecutters Bridge - SCB-WASHMS. 3 ShenzhenShenzhen HIGHWAYS AREA DIVISION DEPARTMENT TSING MA CONTROL BRIDGE HEALTH SECTION ShekouShekou Shenzhen Western YuenYuen LongLong Corridor NewNew TerritoriesTerritories Ting Kau Bridge TuenTuenMun Mun ShaShaTin Tin Tsing Ma Bridge TsingTsingYi Yi Kap Shui Mun Bridge KowloonKowloon Hong Kong HongHong KongKong Stonecutters Bridge InternationalInternational AirportAirport LantauLantau HongHong KongKong IslandIsland IslandIsland 4 Tsing Ma Bridge