KOREA the 38Th Parallel North

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies Cultural Exchange: from Medieval

Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies Volume 1: Issue 1 Cultural Exchange: from Medieval to Modernity AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies JOURNAL OF IRISH AND SCOTTISH STUDIES Volume 1, Issue 1 Cultural Exchange: Medieval to Modern Published by the AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies at the University of Aberdeen in association with The universities of the The Irish-Scottish Academic Initiative and The Stout Research Centre Irish-Scottish Studies Programme Victoria University of Wellington ISSN 1753-2396 Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies Issue Editor: Cairns Craig Associate Editors: Stephen Dornan, Michael Gardiner, Rosalyn Trigger Editorial Advisory Board: Fran Brearton, Queen’s University, Belfast Eleanor Bell, University of Strathclyde Michael Brown, University of Aberdeen Ewen Cameron, University of Edinburgh Sean Connolly, Queen’s University, Belfast Patrick Crotty, University of Aberdeen David Dickson, Trinity College, Dublin T. M. Devine, University of Edinburgh David Dumville, University of Aberdeen Aaron Kelly, University of Edinburgh Edna Longley, Queen’s University, Belfast Peter Mackay, Queen’s University, Belfast Shane Alcobia-Murphy, University of Aberdeen Brad Patterson, Victoria University of Wellington Ian Campbell Ross, Trinity College, Dublin The Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies is a peer reviewed journal, published twice yearly in September and March, by the AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies at the University of Aberdeen. An electronic reviews section is available on the AHRC Centre’s website: http://www.abdn.ac.uk/riiss/ahrc- centre.shtml Editorial correspondence, including manuscripts for submission, should be addressed to The Editors,Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies, AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies, Humanity Manse, 19 College Bounds, University of Aberdeen, AB24 3UG or emailed to [email protected] Subscriptions and business correspondence should be address to The Administrator. -

Miles, Stephen Thomas (2012) Battlefield Tourism: Meanings and Interpretations

Miles, Stephen Thomas (2012) Battlefield tourism: meanings and interpretations. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/3547/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Battlefield Tourism: Meanings and Interpretations Stephen Thomas Miles B.A. (Hons.) Dunelm, M.A. Sheffield Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy College of Arts University of Glasgow 2012 Dedicated to Dr Howard Thomas Miles (1931-2006) Abstract Battlefield sites are some of the most iconic locations in any nation’s store of heritage attractions and continue to capture the imagination of visitors. They have strong historic, cultural, nationalistic and moral resonances and speak to people on a national as well as a local scale. They have the power to provoke contention but at the same time foster understanding and respect through the consideration of deep moral questions. Battlefields are suffused with powerful stories of courage, sacrifice, betrayal and even cowardice. They have a strong sense of place and can provoke a range of cognitive and emotional reactions. -

+Roodqgh Fodlp Jlyhv 5Didoh Ghdo Qhz Wzlvw

$ % RNI Regn. No. CHHENG/2012/42718, Postal Reg. No. - RYP DN/34/2013-2015 @+4 2 ! A A A 3#"536 4%7 ,-./ **+ &'() $3&+;3&3,5+D CD/;4D5;C ,9+&.2;$+ ;/$D3%$3.2;3 %;;4&+ B7:5&3C+;.5+ & ; = 33/ '7: > " 8 + ((8 ()49 ( : Q ! "$% !& 234 ! "01 - R 3.45 New Delhi. India on Thursday gave green signal to the meet- day after the Modi ing following Pakistan Prime AGovernment confirmed Minister’s September 15 letter External Affairs Minister to Prime Minister Narendra Sushma Swaraj’s talks with her Modi seeking the resumption Pakistani counterpart Shah of dialogue between the two Mehmood Qureshi on the side- countries. lines of the upcoming United On Friday, the MEA said, Nations General Assembly “After Imran Khan’s letter, we (UNGA) in New York next thought Pakistan is moving week, India on Friday called off towards positive changes, a the meeting citing Pakistan’s new beginning. But now it complicity in the “brutal” seems behind their proposal killing of three policemen in were evil intentions.” Jammu & Kashmir as well as India is also furious over the release of postal stamps glo- the release of 20 special stamps rifying Kashmiri terrorist by Islamabad glorifying Burhan Burhan Wani. Wani — the Hizbul Accusing Pakistan and Mujahideen terrorist killed by Prime Minister Imran Khan of security forces in 2016 — in the “evil designs” after three police- guise of solidarity with men were kidnapped and killed Kashmiris. by terrorists in Shopian in While agreeing to the J&K, India said talks with meeting after Imran Khan’s Pakistan in such an environ- request, New Delhi had sought ! " ment would be “meaningless”. -

México Beyond 1968

MÉXICO BEYOND 1968 EDITED BY JAIME M. PENSADO AND ENRIQUE C. OCHOA MÉXICO BEYOND 1968 Revolutionaries, Radicals, and Repression During the Global Sixties and Subversive Seventies The University of Arizona Press www .uapress .arizona .edu © 2018 by The Arizona Board of Regents All rights reserved. Published 2018 ISBN- 13: 978- 0- 8165- 3842- 3 (paper) Cover design by Leigh McDonald Cover illustration: Libertad de expresión by Adolfo Mexiac, 1968 This book is made possible in part by support from the Institute for Scholarship in the Liberal Arts, College of Arts and Letters, University of Notre Dame. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Pensado, Jaime M., 1972– editor. | Ochoa, Enrique, editor. Title: México beyond 1968 : revolutionaries, radicals, and repression during the global sixties and subversive seventies / edited by Jaime M. Pensado and Enrique C. Ochoa. Description: Tucson : The University of Arizona Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018008709 | ISBN 9780816538423 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Mexico—Politics and government—20th century. | Mexico—Social conditions— 20th century. | Social movements—Mexico—History—20th century. | Protest movements— Mexico—History—20th century. | Political culture—Mexico—History—20th century. Classification: LCC F1236 M47166 2018 | DDC 972.08/2—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn .loc .gov /2018008709 Printed in the United States of America ♾ This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48- 1992 (Permanence of Paper). CONTENTS Preface: Mexico Today ix Jaime M. Pensado and Enrique C. Ochoa Acknowledgments xvii Introduction: México Beyond 1968: Revolutionaries, Radicals, and Repression 3 Jaime M. Pensado and Enrique C. Ochoa PART I. -

Preface Ho Chi Minh: “A Great Man of Culture”

PREFACE HO CHI MINH: “A GREAT MAN OF CULTURE” n November 1987, in anticipation of the centenary of the birth Iof Ho Chi Minh in 1990, the General Conference of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) considered that “the international celebration of the anniversaries of eminent intellectual and cultural personalities contributes to the realization of UNESCO’s objectives and to international understanding,” and passed resolutions to recognize Ho Chi Minh as among the “great personalities … [who] have left an imprint on the development of the humanity.”iv The Gen- eral Conference acknowledged Ho Chi Minh as “a Vietnamese hero of national liberation and great man of culture”and “an out- standing symbol of national affirmation. [He] devoted his whole life to the national liberation of the Vietnamese people, contribut- ing to the common struggle of peoples for peace, national inde- pendence, democracy and social progress.”v The resolutions also suggested that the important and many-sided contribution of Presi- dent Ho Chi Minh in the field of culture, education and the arts crystallizes the cultural tradition of the Viet- namese people which stretches back several thousand years, and that his ideals embody the aspirations of peo- ples in the affirmation of their cultural identity and the promotion of mutual understanding.vi The General Conference encouraged the Member States to join in the commemoration “as a tribute to his memory, in order to spread knowledge of the greatness of his ideals and of his work for national liberation.”vii Ho Chi Minh’s work for national lib- eration was best known through his claiming independence for Vietnam from French colonialism. -

Pedlars of Hate: the Violent Impact of the European Far Right

Pedlars of hate: the violent impact of the European far Right Liz Fekete Published by the Institute of Race Relations 2-6 Leeke Street London WC1X 9HS Tel: +44 (0) 20 7837 0041 Fax: +44 (0) 20 7278 0623 Web: www.irr.org.uk Email: [email protected] ©Institute of Race Relations 2012 ISBN 978-0-85001-071-9 Acknowledgements We would like to acknowledge the support of the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust and the Open Society Foundations in the researching, production and dissemination of this report. Many of the articles cited in this document have been translated into English by over twenty volunteers who assist the IRR’s European Research Programme. We would especially like to thank Sibille Merz and Dagmar Schatz (who translate from German into English), Joanna Tegnerowicz (who translates from Polish into English) and Kate Harre, Frances Webber and Norberto Laguía Casaus (who translate from Spanish into English). A particular debt is due to Frank Kopperschläger and Andrei Stavila for their generosity in allowing us to use their photographs. In compiling this report the websites of the Internet Centre Against Racism in Europe (www.icare.to) and Romea (www.romea.cz) proved invaluable. Liz Fekete is Executive Director of the Institute of Race Relations and head of its European research programme. Cover photo by Frank Kopperschläger is of the ‘Silence Against Silence’ memorial rally in Berlin on 26 November 2011 to commemorate the victims of the National Socialist Underground. (In Germany, white roses symbolise the resistance movement to the Nazi -

Asia's New Order and Cooperative Leadership

2016 Asia’s New Order and Cooperative Leadership 아시아의 새로운 질서와 협력적 리더십 Asia’s New Order and Cooperative Leadership 아시아의 새로운 질서와 협력적 리더십 Jeju Forum Secretariat CONTENTS [ Opening Remarks ] WON Heeryong ‘Silk Road of Peace’ to Common Prosperity • 008 [ Keynote Speech ] HWANG Kyo-ahn Towards a New Era of Asia • 010 BAN Ki-moon Global Progress Depends on Solidarity • 013 Tomiichi MURAYAMA A Genuine Apology for Reconciliation • 017 Mahathir bin MOHAMAD Being Civilized Means Making Peace Not War • 020 Jim BOLGER Reducing Nuclear Weapons down to Zero • 023 GOH Chok Tong Collective Wisdom for a Better Future • 027 Enrico LETTA Education, Key to Cooperative Leadership • 031 [ Dinner Speech ] HONG Yong-pyo A Journey to Peaceful Unification • 034 [ Closing Remarks ] MOON Tae-young Jeju Forum to Continue Promoting Peace • 036 Chapter ONE [ World Leaders Session ] Asia’s New Order and Cooperative Leadership • 040 Geopolitical Tensions and Nuclear Temptations in Asia-Pacific • 043 Trilateral Views: Promoting Nuclear Safety Cooperation in Northeast Asia • 046 The Past Achievements and Future Directions of the UN GGE in Information Security • 048 PEACE Nuclear Security and Safety in Asia-Pacific: Old Issues and New Thinking • 052 [ Dialogue with Johan Galtung ] Northeast Asia in Tension, Seeking for Peace • 054 The Jeju Forum for Peace and Prosperity discusses how multilateral cooperation in the region can promote mutual peace and prosperity on the Korean Unification and the Role and Future of the ROK-US Alliance • 056 Korean Peninsula and in East Asia. After being launched in 2001 as the Jeju peace Forum, it was renamed the Jeju Forum for Peace and Prosperity Towards New Cooperative Leadership in Asia: Theory and Practice • 059 in its sixth session in 2011. -

He Vigilance Commission Alleging Gating His Role in at Least Half a Court on Two Occasions

% . RNI Regn. No. MPENG/2004/13703, Regd. No. L-2/BPLON/41/2006-2008 A+4 2 ! B B B 3#"536 4&7 *+00*6 3*45!! /0/,0-1!2 =C/;4C5;= $3&+;3&3,5+C .C.;,3 %;;4&+ ;/$C3%$3.2;3 53&$ & ; 7 33/ '7> ? " 8 , ))8 )*49 ):7 ;+* Q ! "$% !& &7 $ R % 3.45 for the meeting rather than the New Delhi. India on Thursday day after the Modi gave green signal to the meet- AGovernment confirmed ing following Pakistan Prime External Affairs Minister Minister’s September 15 letter Sushma Swaraj’s talks with her to Prime Minister Narendra Pakistani counterpart Shah Modi seeking the resumption Mehmood Qureshi on the side- of dialogue between the two lines of the upcoming United countries. Nations General Assembly On Friday, the MEA said, (UNGA) in New York next “After Imran Khan’s letter, we 3.45 week, India on Friday called off thought Pakistan is moving the meeting citing Pakistan’s towards positive changes, a n a significant development, complicity in the “brutal” new beginning. But now it Ia French media report quot- killing of three policemen in seems behind their proposal ed former French President Jammu & Kashmir as well as were evil intentions.” Francois Hollande as purport- the release of postal stamps glo- India is also furious over edly saying that the Indian Government nor the French not have a choice, we took the rifying Kashmiri terrorist the release of 20 special stamps Government proposed Government had any say in the partner who was given to us.” Burhan Wani. -

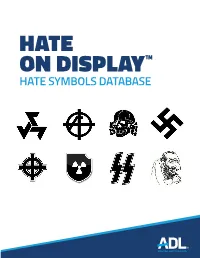

Hate Symbols Database

HATE ON DISPLAY™ HATE SYMBOLS DATABASE 1 HATE ON DISPLAY This database provides an overview of many of the symbols most frequently used by a variety of white supremacist groups and movements, as well as some other types of hate groups. You can find the full listings at adl.org/hate-symbols INTRODUCTION TO THE HATE ON DISPLAY HATE SYMBOLS DATABASE ADL is a leading anti-hate organization that was founded in 1913 in response to an escalating climate of anti-Semitism and bigotry. Today, ADL is the first call when acts of anti-Semitism occur and continues to fight all forms of hate. A global leader in exposing extremism, delivering anti-bias education and fighting hate online, ADL’s ultimate goal is a world in which no group or individual suffers from bias, discrimination or hate. ADL’s Center on Extremism debuted its Hate on Display hate symbols database in 2000, establishing the database as the first and foremost resource on the internet for symbols, codes, and memes used by white supremacists and other types of haters. Over the past two decades, Hate on Display has regularly been updated with new symbols and images as they have come into common use by extremists, as well as new functions to make it more useful and convenient for users. Although the database contains many examples of online usage and shared graphics, another feature that makes it unique is its emphasis on real world examples of hate symbols—showing them as extremists actually use them: on signs and clothing, graffiti and jewelry, and even on their own bodies as tattoos and brands. -

Nazism and Neo-Nazism in Film and Media Nazism and Neo-Nazism in Film and Media

JASON LEE Nazism and Neo-Nazism in Film and Media Nazism and Neo-Nazism in Film and Media Nazism and Neo-Nazism in Film and Media Jason Lee Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Girl Scout confronts neo-Nazi at Czech rally. Photo: Vladimir Cicmanec Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 90 8964 936 2 e-isbn 978 90 4852 829 5 doi 10.5117/9789089649362 nur 670 © J. Lee / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2018 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Contents Acknowledgements 7 1. Introduction – Beliefs, Boundaries, Culture 9 Background and Context 9 Football Hooligans 19 American Separatists 25 2. Film and Television 39 Memory and Representation 39 Childhood and Adolescence 60 X-Television 66 Conclusions 71 3. Nazism, Neo-Nazism, and Comedy 75 Conclusions – Comedy and Politics 85 4. Necrospectives and Media Transformations 89 Myth and History 89 Until the Next Event 100 Trump and the Rise of the Right 107 Conclusions 116 5. Globalization 119 Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America 119 International Nazi Hunters 131 Video Games and Conclusions 135 6. Conclusions – The Infinitely Other 141 Evil and Violence 141 Denial and Memorial 152 Europe’s New Far Right and Conclusions 171 Notes 189 Bibliography 193 Index 199 Acknowledgements A special thank you to Stuart Price, Chair of the Media Discourse Group at De Montfort University (DMU). -

US-Philippine Relations, 1946-1972

Demanding Dictatorship? US-Philippine Relations, 1946-1972. A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2016 Ben Walker School of Arts, Languages and Cultures 2 Contents Abstract. 3 Declaration and Copyright Statement. 4 Acknowledgements. 5 Introduction. From Colony to Cold War Ally: The Philippines and American Foreign Policy, 1898-1972. 6 1. ‘What to do with the Philippines?’ Economic Forces and Political Strategy in the United States’ Colonial Foreign Policy. 28 2. A New World Cold War Order: ‘Philippine Independence’ and the Origins of a Neo-Colonial Partnership. 56 3. To Fill the Void: US-Philippine Relations after Magsaysay, 1957-1963. 87 4. The Philippines after Magsaysay: Domestic realities and Cold War Perceptions, 1957-1965. 111 5. The Fall of Democracy: the First Term of Ferdinand Marcos, the Cold War, and Anti-Americanism in the Philippines, 1966-1972. 139 Conclusion. ‘To sustain and defend our government’: the Declaration of Martial Law, and the Dissolution of the Third Republic of the Philippines. 168 Bibliography. 184 Word Count: 80, 938. 3 Abstract In 1898 the Philippines became a colony of the United States, the result of American economic expansion throughout the nineteenth century. Having been granted independence in 1946, the nominally sovereign Republic of the Philippines remained inextricably linked to the US through restrictive legislation, military bases, and decades of political and socio-economic patronage. In America’s closest developing world ally, and showcase of democratic values, Filipino President Ferdinand Marcos installed a brutal dictatorship in 1972, dramatically marking the end of democracy there. -

Rethinking Missionaries from 1910 to Today

"Rethinking Missionaries" from 1910 to Today Dana L. Robert In 1910, 1200 representatives of Protestant missionary societies met in Edinburgh, Scotland, to consider the meaning of Christian mission for their generation. In 2010, we gather as part of a worldwide network of meetings asking the same question. What has been the shape of Christian mission over the past century, and what is its future? Because human beings are God's hands and feet at work in the world, we must also ask the related question: What has it meant to be a missionary over the course of the last century? And most relevant to our gathering today, what does it mean to be United Methodist missionaries today? To "rethink mission" requires that we also "rethink missionaries," both for our own generation, and for those who will follow. Although apostolic vocation is a timeless calling, the work of mission takes its cue from its contemporary sociocultural context. Nobody expressed this as well as the great 20th century Methodist missionary E. Stanley Jones, who wrote in The Christ of the India Road, "Evangelize the inevitable." In other words, the missionary must bring the Gospel into contact with whatever is going on in the world. To "evangelize the inevitable" requires crossing boundaries to witness to Jesus Christ. But the nature of those boundaries changes according to the circumstances of each age. In this address, I will reflect on a few of the changing definitions of " missionary" from 1910 to today. "Rethinking missionaries" means asking what it means for us to "evangelize the inevitable." Except for the proverbial death and taxes, what seemed inevitable a century ago does not seem inevitable a hundred years later.