The Causes of Growth During Belgium's Industrial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Base Maps in Belgium

Belgeo Revue belge de géographie 1-2-3-4 | 2000 Special issue: 29th International Geographical Congress Base maps in Belgium Philippe De Maeyer Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/belgeo/13977 DOI: 10.4000/belgeo.13977 ISSN: 2294-9135 Publisher: National Committee of Geography of Belgium, Société Royale Belge de Géographie Printed version Date of publication: 30 December 2000 Number of pages: 165-172 ISSN: 1377-2368 Electronic reference Philippe De Maeyer, « Base maps in Belgium », Belgeo [Online], 1-2-3-4 | 2000, Online since 12 July 2015, connection on 19 April 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/belgeo/13977 ; DOI : 10.4000/belgeo.13977 This text was automatically generated on 19 April 2019. Belgeo est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. Base maps in Belgium 1 Base maps in Belgium Philippe De Maeyer Introduction 1 Although Belgium has had its own base cartography organised on a national scale for over a century, the federalisation process and the new regional structures which resulted have redrawn the landscape of base cartography production in this country. 2 The succession of constitutional reforms during the 1970s and 80s gave birth to a new Belgium, one based on legislative and executive powers both at the national level and at the level of the Communities and the Regions. The Community concept relates to the persons who compose it and to the ties which bind them together (language, culture, etc.). The Regions have competencies in the areas affecting the use of the ‘territory’, in the broad meaning of that term. -

Welcome Guide for International Students of the Pole Hainuyer 1 03 Word of the Editor

WELCOME GUIDE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS OF THE POLE HAINUYER 1 03 WORD OF THE EDITOR 04 BELGIUM IN A NUTSHELL 05 EDUCATION 05 Higher education in the Wallonia-Brussels Federation 06 The Pôle hainuyer, a higher education centre in Hainaut 07 Studying at an institution of the Pôle hainuyer 08 International Relations departments 10 Academic calendar French language courses CONTENT 11 11 Libraries 12 Student life 14 Culture and Sports 16 USEFUL INFORMATION 16 Administrative procedures 18 Transport 20 Accommodation 22 Health 24 Day-to-day life 25 MAPS 25 Tournai 26 Mons 27 Charleroi 28 Hainaut 30 Details 36 CONTACTS PUBLISHED BY CO-ORDINATION ILLUSTRATIONS Photographies Design Pôle Hainuyer asbl & EDITING Pierre Kroll UMONS, exnihilo.be Place du parc, 20 Lydie Lejuste © Tous droits réservés HEPH-Condorcet, 7000 Mons HELHa, ARTS2 WORD OF THE EDItoR Dear student, You have chosen to spend your mobility for studies or traineeship in the Pôle hainuyer, structure which gather higher education institutions of the Province of Hainaut in Belgium. We are very happy to welcome you here and we will do our best to ensure your mobility experience is as profitable and pleasant as possible. This guide you are holding now provides useful information and advice that will make it easier to prepare your journey and ensure your stay runs smoothly. You are now ready to discover a new living environment. Many questions probably play on your mind: who to get in touch with upon your arrival… and before your departure? How can you travel to the host city by public transport? How should you book your accommodation? What kind of insurance do you need to subscribe? We will try to answer those questions to the best of our abilities in this document. -

Interreg I / Ii : Cross-Border Cooperation

INTERREG I / II : CROSS-BORDER COOPERATION Euregio Meuse-Rhine: implementation and management in practice Speech by Mr K.H. Lambertz - Chair of the Monitoring Committee for the Euregio Meuse-Rhine Interreg Programme - Director of Euregio Meuse-Rhine - Minister-President of the German-speaking community of Belgium 1. General background and geographical situation In 1974, the governors of the Dutch and Belgian provinces of Limburg, together with the Chief Executive of the Cologne county administration, acted on the proposal made to them by the future Queen of the Netherlands, Princess Beatrix, during an official visit to Maastricht, to draw up draft arrangements for an association under which even closer cross-border collaboration could develop, along the lines of the Dutch-German Euregio project that had been running since 1957. This initiative was part of the new Community direction in regional policy, which in 1975 was to be provided with an instrument to assist economic development called the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF). In 1976, the principle of cross-border institutions was passed in law. Initially formed as an ad hoc association, the Euregio Meuse-Rhine was designed to promote integration between inhabitants on each side of the national borders. The area covers: • in Holland: the southern part of the Dutch province of Limburg; • in Germany: the city of Aachen, and the districts of Aachen, Heinsberg, Düren and Euskirchen, which make up the Aachen Regio, and • in Belgium: the entire province of Limburg. The province of Liège joined the Euregio Meuse-Rhine in 1978. In 1992, the German-speaking community of Belgium became the fifth partner in the Euregio Meuse- Rhine. -

1 the DUTCH DELTA MODEL for POLICY ANALYSIS on FLOOD RISK MANAGEMENT in the NETHERLANDS R.M. Slomp1, J.P. De Waal2, E.F.W. Ruijg

THE DUTCH DELTA MODEL FOR POLICY ANALYSIS ON FLOOD RISK MANAGEMENT IN THE NETHERLANDS R.M. Slomp1, J.P. de Waal2, E.F.W. Ruijgh2, T. Kroon1, E. Snippen2, J.S.L.J. van Alphen3 1. Ministry of Infrastructure and Environment / Rijkswaterstaat 2. Deltares 3. Staff Delta Programme Commissioner ABSTRACT The Netherlands is located in a delta where the rivers Rhine, Meuse, Scheldt and Eems drain into the North Sea. Over the centuries floods have been caused by high river discharges, storms, and ice dams. In view of the changing climate the probability of flooding is expected to increase. Moreover, as the socio- economic developments in the Netherlands lead to further growth of private and public property, the possible damage as a result of flooding is likely to increase even more. The increasing flood risk has led the government to act, even though the Netherlands has not had a major flood since 1953. An integrated policy analysis study has been launched by the government called the Dutch Delta Programme. The Delta model is the integrated and consistent set of models to support long-term analyses of the various decisions in the Delta Programme. The programme covers the Netherlands, and includes flood risk analysis and water supply studies. This means the Delta model includes models for flood risk management as well as fresh water supply. In this paper we will discuss the models for flood risk management. The issues tackled were: consistent climate change scenarios for all water systems, consistent measures over the water systems, choice of the same proxies to evaluate flood probabilities and the reduction of computation and analysis time. -

41. the Meuse–Rhine Euroregion: a Laboratory for Police and Judicial Cooperation in the European Union*

41. THE MEUSE–RHINE EUROREGION: A LABORATORY FOR POLICE AND JUDICIAL COOPERATION IN THE EUROPEAN UNION* 1. Introduction Over the past few decades, economic and social integration within the European Union (EU) has rapidly gained momentum. This integration has been largely facili- tated by the Schengen Implementation Convention of 1990, which abolished border controls between the member states.1 However, this easing of border controls has also improved and expanded the opportunities for criminals to engage in cross-border illegal activities. Therefore, police and judicial cooperation has now become a high priority on the European Union’s agenda. The authorities in urbanized border areas are usually the first to be confronted by new developments in cross-border crime. As a result, opportunities for law- enforcement cooperation are quickly grasped, and practical innovations are devised as far as the conventions permit. Hence, border areas often serve as ‘laboratories’ for police and judicial cooperation. A clear example of this is the Meuse-Rhine Euroregion, located in the border areas of the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany. From a scholarly point of view, jurists have largely dominated the discussion about police and judicial cooperation (Corstens and Pradel 2002; Peers 2000; Sabatier 2001). This is easily explained by the fact that up until now criminologists have con- ducted relatively little empirical research on this topic. However, the Meuse-Rhine Euroregion is an exception to the rule, as several studies about police and judicial cooperation with regard to the area have been published over the years (Hofstede and Faure 1993; Spapens 2002, 2008a; Spapens and Fijnaut 2005). -

The Dutch Delta Model to Support National Policy Analysis Erik Ruijgh

The Dutch Delta model to support national policy analysis Erik Ruijgh Deltares, the Netherlands 16 maart 2016 Water management in the Netherlands Water management in the Netherlands Water management in the Netherlands Delta programme Historically, measures were implemented AFTER a disaster. The Dutch government started the Delta programme to implement a series of measures to PREVENT new disasters. Focus on consequences of climate change and socio-economic development. Both flood risk, drought management and spatial planning are included. Delta…. • Delta commission • Delta commissoner • Delta act • Delta fund • Delta programme • Delta decisions • Delta model / Delta scenarios Delta programme Generic sub-programs: • Flood protection • Fresh water supply • Reallocation and renovation IJsselmeer region Regional sub-programs: • Coast • Wadden region Rhine-Meuse Rivers • Southwest Delta estuary • Rivers Southwest Delta • Rhine Meuse estuary • Lake IJsselmeer region Planning 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 Delta programme Possible Promissing Preferred Implementation strategies strategies strategies Delta model - 0.2 1.0 1.1 1.2 Screening Subprograms National Delta decisions DP2013 DP2014 DP2015 DP2016 9 Delta scenarios social economic growth Busy Steam change climate rapid Quiet Warm moderate climate chnage climate moderate chnage social economic squeeze Delta scenarios: urban development 1900 1960 2010 The Delta model: a coherent set of models original situation Deltamodel measure, scenario database model impact assessment Delta model components for -

Belgian Identity Politics: at a Crossroad Between Nationalism and Regionalism

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2014 Belgian identity politics: At a crossroad between nationalism and regionalism Jose Manuel Izquierdo University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Human Geography Commons Recommended Citation Izquierdo, Jose Manuel, "Belgian identity politics: At a crossroad between nationalism and regionalism. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2014. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/2871 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Jose Manuel Izquierdo entitled "Belgian identity politics: At a crossroad between nationalism and regionalism." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Geography. Micheline van Riemsdijk, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Derek H. Alderman, Monica Black Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Belgian identity politics: At a crossroad between nationalism and regionalism A Thesis Presented for the Master of Science Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Jose Manuel Izquierdo August 2014 Copyright © 2014 by Jose Manuel Izquierdo All rights reserved. -

Belgium-Luxembourg-7-Preview.Pdf

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Belgium & Luxembourg Bruges, Ghent & Antwerp & Northwest Belgium Northeast Belgium p83 p142 #_ Brussels p34 Wallonia p183 Luxembourg p243 #_ Mark Elliott, Catherine Le Nevez, Helena Smith, Regis St Louis, Benedict Walker PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to BRUSSELS . 34 ANTWERP Belgium & Luxembourg . 4 Sights . 38 & NORTHEAST Belgium & Luxembourg Tours . .. 60 BELGIUM . 142 Map . 6 Sleeping . 62 Antwerp (Antwerpen) . 144 Belgium & Luxembourg’s Eating . 65 Top 15 . 8 Around Antwerp . 164 Drinking & Nightlife . 71 Westmalle . 164 Need to Know . 16 Entertainment . 76 Turnhout . 165 First Time Shopping . 78 Lier . 167 Belgium & Luxembourg . .. 18 Information . 80 Mechelen . 168 If You Like . 20 Getting There & Away . 81 Leuven . 174 Getting Around . 81 Month by Month . 22 Hageland . 179 Itineraries . 26 Diest . 179 BRUGES, GHENT Hasselt . 179 Travel with Children . 29 & NORTHWEST Haspengouw . 180 Regions at a Glance . .. 31 BELGIUM . 83 Tienen . 180 Bruges . 85 Zoutleeuw . 180 Damme . 103 ALEKSEI VELIZHANIN / SHUTTERSTOCK © SHUTTERSTOCK / VELIZHANIN ALEKSEI Sint-Truiden . 180 Belgian Coast . 103 Tongeren . 181 Knokke-Heist . 103 De Haan . 105 Bredene . 106 WALLONIA . 183 Zeebrugge & Western Wallonia . 186 Lissewege . 106 Tournai . 186 Ostend (Oostende) . 106 Pipaix . 190 Nieuwpoort . 111 Aubechies . 190 Oostduinkerke . 111 Ath . 190 De Panne . 112 Lessines . 191 GALERIES ST-HUBERT, Beer Country . 113 Enghien . 191 BRUSSELS P38 Veurne . 113 Mons . 191 Diksmuide . 114 Binche . 195 MISTERVLAD / HUTTERSTOCK © HUTTERSTOCK / MISTERVLAD Poperinge . 114 Nivelles . 196 Ypres (Ieper) . 116 Waterloo Ypres Salient . 120 Battlefield . 197 Kortrijk . 123 Louvain-la-Neuve . 199 Oudenaarde . 125 Charleroi . 199 Geraardsbergen . 127 Thuin . 201 Ghent . 128 Aulne . 201 BRABO FOUNTAIN, ANTWERP P145 Contents UNDERSTAND Belgium & Luxembourg Today . -

À La Communauté D'agglomération Maubeuge

Le faire-part foncier de l’EPF Nord - Pas de Calais à la Communauté d’agglomération Maubeuge - Val de Sambre JEUMONT MAUBEUGE AULNOYE-AYMERIES L’Etablissement Public Foncier Nord - Pas de Calais (EPF), créé en 1990, s’est investi de façon opérationnelle sur les questions foncières, et, au-delà de la requalification des fonciers dégradés des friches industrielles, a voulu apporter un concours aux territoires dans la formulation et la mise en œuvre de leur stratégie foncière. Dans le contexte actuel de crise du logement et de relance des politiques publiques d’habitat, l’intérêt des collectivités est de mettre en œuvre, en amont du développement attendu de leur territoire, des politiques d’aménagement. L’efficacité de ces politiques dépend de la qualité de la stratégie foncière élaborée, mais le plus souvent les collectivités publiques ne disposent pas ou trop peu d’outils de connaissance stratégique du foncier. L’Atelier des méthodologies du foncier (AMF) s’inscrit dans cette démarche. Il a pour but de proposer des méthodes d’observation et de mesure des mutations foncières transposables à l’échelle des collectivités. Il constitue un lieu de ressource permettant d’affiner des méthodologies adaptées aux spécificités des territoires de la région afin : - d’accompagner les intercommunalités dans l’élaboration des stratégies foncières de leur projet de territoire, - de les aider à mettre en place les traductions spatiales et opérationnelles qui en découlent, - et de participer à leur suivi et à leur évaluation tant au regard de politiques publiques que du point de vue global de la gestion des usages du foncier. -

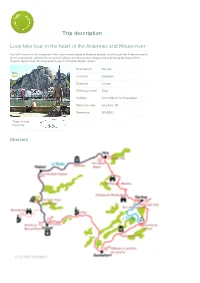

Trip Description Loop Bike Tour in the Heart of the Ardennes and Meuse

Trip description Loop bike tour in the heart of the Ardennes and Meuse river You will have so much to explore in this undisclosed region of Belgium by bike: ride through the Ardennes and its green countryside, discover the provincial folklore and picturesque villages and relax along the banks of the majestic Meuse river. What a pleasant way of living the Belgian dream! Destination Europe Location Belgique Duration 5 days Difficulty Level Easy Validity from March to November Minimum age 12 years old Reference WA0501 Type of stay loop trip Itinerary Leave your problems behind as suggests a famous Belgian proverb and be part of this fabulous bike trip in the great outdoors of both the Ardennes and along the Meuse river. Naturally you will be amazed by the renowned Belgian good mood! Your trip begins in Dinant, the city where Adolphe Sax, the inventor of the musical instrument, was born. Enjoy the most charming places of the Ardennes such as Rochefort, Marche-en-Famenne or Durbuy and cross picturesque landscapes. You ride sometimes on small countryside roads, on large cycle paths or along the Meuse river between Huy and Dinant passing by Namur, the capital of Wallonia. All the ingredients are combined in this loop bike tour to enjoy a great adventure! Eager for culture? Explore the citadels of Namur and Dinant, the castel of Modave or the fort of Huy. Keen to relax in the nature? The natural area of Leffe and Famenne regions or the peaceful banks of the Meuse river await you! Not to mention the Belgian gastronomy with its French fries, its waffles, its chocolate or all types of beers: all your senses will be awake! Day 1 Dinant - Rochefort Get onto your bike for a perfect adventure! Dinant is your starting point and you will find plenty of activities to enjoy there. -

Alstom in Belgium

ALSTOM IN BELGIUM In Belgium, Alstom is a major player in sustainable mobility with 2 global centres of excellence: the first in electrical energy conversion and storage (traction and energy efficiency) and the second in signalling for mainlines. The development of these activities is based on significant R&D investments to ensure safer and more efficient rail transport while offering environmentally friendly solutions. Alstom is present in Belgium with 1 production site in Charleroi and 2 depots for service activities in Antwerp and Fleurus. The Alstom Benelux headquartered is in Brussels. : ACTIVITY 1 - SIGNALLING – The centre of excellence develops national signalling solutions and also based on the European standard ERTMS (European Railway Traffic Management System). Developments relate to equipment on the tracks and on board trains. These systems manage train safety and increase train frequency. – Alstom is at the forefront of the development of autonomous transport systems. Its Automatic Train Operation (ATO) system maximises network capacity, energy savings and punctuality. : ACTIVITY 2 – COMPONENTS & ENERGY SOLUTIONS – The center of excellence mobilizes its technological expertise to develop and industrialize new-generation traction systems to meet the current and future needs of operators and passengers. Traction systems equip a KEY FIGURES significant part of Alstom's rolling stock, notably regional trains, metros and tramways. 1250 employees – R&D programs are dedicated to reducing the energy consumption of solutions and developing energy 4 sites and depots recovery systems. MORE INFORMATION: 100 Projects around the world : ACTIVITY 3 - SERVICESAlstom 50-51 rue Cambier Dupret – A panel of services is6001 offered Charleroi to guarantee- Belgium the availability 20 R&D programmes of systems: parts andTel: repairs, +32 71 44 modernization, 54 11 development engineering, technical support, integrated 8 Place Marcel Broodthaersplein logistics support, tools1060 and Brussels test –benchesBelgium using new technologies. -

Nos Missions, Nos Valeurs. Le Plan Stratégique Et Opérationnel De La Province De Hainaut APPRENDRE I DÉCOUVRIR I PRÉSERVER I PARTAGER I MIEUX VIVRE

APPRENDRE I DÉCOUVRIR I PRÉSERVER I PARTAGER I MIEUX VIVRE Nos missions, nos valeurs. Le plan stratégique et opérationnel de la Province de Hainaut APPRENDRE I DÉCOUVRIR I PRÉSERVER I PARTAGER I MIEUX VIVRE Nos missions, nos valeurs. 3 Le plan stratégique et opérationnel de la Province de Hainaut Sommaire Préface Introduction 6 Une ADhésioN au développement du Hainaut De quoi parle-t-on ? 8 Depuis 2012, la Province de Hainaut décline ses actions et projets en faveur de la Première partie population au travers d’un plan stratégique et opérationnel opportunément appelé ADhésioN. L’ Institution y définit ses valeurs, ses axes prioritaires et les moyens tant Apprendre 10 humains que financiers nécessaires pour les concrétiser. Le Hainaut se trouve ainsi doté Découvrir 12 d’une véritable feuille de route, forte de près de 500 projets et activités. Préserver 14 Partager 16 Engagée dans le soutien aux communes et active dans la dynamique des territoires, la Mieux vivre 18 Province a fait le pari d’une gouvernance renouvelée. Son champ d’action en faveur du citoyen se trouve clairement défini. Les services rendus le sont dans le respect d’une 4 Deuxième partie stricte maîtrise budgétaire. 5 La gouvernance et le développement durable 20 La Province, partenaire des grands enjeux de développement du Hainaut et du bien- L’intérêt général et la solidarité 26 être citoyen : c’est désormais une réalité quotidienne. Au travers d’actions exemplaires, La citoyenneté et le bien-être 32 ce document s’emploie à démontrer que les valeurs de citoyenneté, d’intérêt général, L’excellence et l’innovation 38 d’excellence et de gouvernance se trouvent inscrites dans l’ADN du Hainaut.