'Gypsies' and 'Anarchists'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women, Old and Aware: Living As a Minority in Extended Care Institutions

WOMEN, OLD AND AWARE: LIVING AS A MINORITY IN EXTENDED CARE INSTITUTIONS by Linda-Mae Campbell B.A., The University of Alberta, 1982 B.S.W., The University of Victoria, 1990 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SOCIAL WORK in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 1998 © Linda-Mae Campbell, 1998 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. 0 Department The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada DE-6 (2/88) Abstract Women Old And Aware: Living As A Minority In Extended Care Institutions The purpose of this phenomenological study was to describe the everyday lived experiences of old, cognitively intact women, residing in an integrated extended care facility among an overwhelming majority of confused elderly people. The research question was "From your perspective, what is the impact of living in an environment where the majority of residents, with whom you reside, are cognitively impaired?". A purposive sample of five older women participated in multiple in-depth interviews about their subjective experiences. -

Republic of Serbia Ipard Programme for 2014-2020

EN ANNEX Ministry of Agriculture and Environmental Protection Republic of Serbia REPUBLIC OF SERBIA IPARD PROGRAMME FOR 2014-2020 27th June 2019 1 List of Abbreviations AI - Artificial Insemination APSFR - Areas with Potential Significant Flood Risk APV - The Autonomous Province of Vojvodina ASRoS - Agricultural Strategy of the Republic of Serbia AWU - Annual work unit CAO - Competent Accrediting Officer CAP - Common Agricultural Policy CARDS - Community Assistance for Reconstruction, Development and Stabilisation CAS - Country Assistance Strategy CBC - Cross border cooperation CEFTA - Central European Free Trade Agreement CGAP - Code of Good Agricultural Practices CHP - Combined Heat and Power CSF - Classical swine fever CSP - Country Strategy Paper DAP - Directorate for Agrarian Payment DNRL - Directorate for National Reference Laboratories DREPR - Danube River Enterprise Pollution Reduction DTD - Dunav-Tisa-Dunav Channel EAR - European Agency for Reconstruction EC - European Commission EEC - European Economic Community EU - European Union EUROP grid - Method of carcass classification F&V - Fruits and Vegetables FADN - Farm Accountancy Data Network FAO - Food and Agriculture Organization FAVS - Area of forest available for wood supply FOWL - Forest and other wooded land FVO - Food Veterinary Office FWA - Framework Agreement FWC - Framework Contract GAEC - Good agriculture and environmental condition GAP - Gross Agricultural Production GDP - Gross Domestic Product GEF - Global Environment Facility GEF - Global Environment Facility GES -

The Storm Water Drainage and Treatment Systems at the “Gazela”

NOVATECH 2013 The storm water drainage and treatment systems at the “Gazela” bridge in Belgrade, Serbia – A case study Le système de drainage et de traitement des eaux pluviales sur le pont "Gazela" à Belgrade, Serbie – étude de cas Jovan Despotovic1, Jasna Plavšić1, Vanja Zivanovic2 and Nenad 3 Jakovljevic 1 University of Belgrade, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Serbia, [email protected] 2 Cekibeo ltd., Serbia, [email protected] 3 Mostprojekt ltd., Serbia, [email protected] RÉSUMÉ Le pont « Gazela », situé au-dessus de la rivière Sava, fait partie de l'autoroute E75 à Belgrade. Il a été construit en 1970 et reconstruit de 2010 à 2012. Nous décrivons ici le projet de drainage du pont dans le cadre de sa reconstruction. Le pont est situé dans une zone protégée autour de la source d'alimentation en eau potable de Belgrade, et est donc soumis à des contraintes sévères en termes de rejets d’eaux de pluie. Le projet a été conçu sur la base d’une pluie décennale. L'écoulement pluvial de la plate-forme du pont et des voies d'accès s'évacue via de nombreux dispositifs : bouches avaloirs en bord de trottoir, tuyaux installés le long des structures du pont, rejets vers le réseau d’assainissement de Belgrade ou vers des dispositifs de premier flot et rétention/infiltration sur les rives de la rivière Sava. Les tuyaux sont fixés sur la structure du pont au moyen de crochets ou d’ancrages, ou posés sur des rouleaux. Les sous-systèmes comprennent plusieurs éléments de réduction ou en « T », des coudes et des installations pour compenser les différents impacts de la structure du pont, notamment les mouvements ou les affaissements de la structure. -

An Intentional Neurodiverse and Intergenerational Cohousing Community

An Intentional Neurodiverse and Intergenerational Cohousing Community Empowered by Autistic Voices Documented by: ASU team Contact: 612-396-7422 or [email protected] Meeting Agenda Project overview and updates (3-4:30PM) • Overview • Questions from audience • Fill out interest survey • Sign up for volunteer committees Working session (4:45-5:45PM) • Introductions – meet others interested in this community • Visioning exercise • Deeper dive into floor plans and financing • Discuss interest in long term commitments to the project and how to pool funds for land acquisition • Sign up for volunteer committees 2 About ASU ASU (Autism SIBS Universe) is a non-profit organization - 501c3 registered with IRS in 2018 founded by Autistics - support from peers, parents and community members Vision is to create sustainable neurodiverse communities where people with all types of abilities live together to support each other ASU Board members Mix of Autistics, parents and community members 3 Important When are a Neurodiverse community and we welcome people of all abilities We are an intentional community designed with Autistics in mind, but we are NOT an Autism or Disability only housing A community where there is something for everyone Naturally supported safe, trusted and sustainable living for ALL – Independent homes with easy access to COMMUNITY, less isolation, connected relationships, more fun, Healthier and more long term supports For families without Autism For Autistics and their - A GREAT opportunity to families – A safety net for live in a sustainable their children’s future. environment while Better support dealing supporting a neurodiverse with Autism and related community and vice versa challenges. More respite. -

Religion, Ethics, and Poetics in a Tamil Literary Tradition

Tacit Tirukku#a#: Religion, Ethics, and Poetics in a Tamil Literary Tradition The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Smith, Jason William. 2020. Tacit Tirukku#a#: Religion, Ethics, and Poetics in a Tamil Literary Tradition. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard Divinity School. Citable link https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37364524 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA ! ! ! ! ! !"#$%&!"#$%%$&'('& ()*$+$,-.&/%0$#1.&"-2&3,)%$#1&$-&"&!"4$*&5$%)6"67&!6"2$%$,-& ! ! "!#$%%&'()($*+!,'&%&+(&#! -.! /)%*+!0$11$)2!32$(4! (*! 54&!6)781(.!*9!:)';)'#!<$;$+$(.!374**1! $+!,)'($)1!9819$112&+(!*9!(4&!'&=8$'&2&+(%! 9*'!(4&!#&>'&&!*9! <*7(*'!*9!54&*1*>.! $+!(4&!%8-?&7(!*9! 54&!3(8#.!*9!@&1$>$*+! :)';)'#!A+$;&'%$(.! B)2-'$#>&C!D)%%)748%&((%! ",'$1!EFEF! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! G!EFEF!/)%*+!0$11$)2!32$(4! "11!'$>4(%!'&%&';&#H! ! ! ! ! ! <$%%&'()($*+!"#;$%*'I!J'*9&%%*'!6')+7$%!KH!B1**+&.!! ! ! !!/)%*+!0$11$)2!32$(4! ! !"#$%&!"#$%%$&'('&()*$+$,-.&/%0$#1.&"-2&3,)%$#1&$-&"&!"4$*&5$%)6"67&!6"2$%$,-! ! "-%(')7(! ! ! 54$%!#$%%&'()($*+!&L)2$+&%!(4&!!"#$%%$&'(C!)!,*&2!7*2,*%&#!$+!5)2$1!)'*8+#!(4&!9$9(4! 7&+(8'.!BHMH!(4)(!$%!(*#).!)(('$-8(&#!(*!)+!)8(4*'!+)2&#!5$'8;)NN8;)'H!54&!,*&2!7*+%$%(%!*9!OCPPF! ;&'%&%!)'')+>&#!$+(*!OPP!74),(&'%!*9!(&+!;&'%&%!&)74C!Q4$74!)'&!(4&+!#$;$#&#!$+(*!(4'&&!(4&2)($7! -

Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

individualist anarchism against bosses, inequality, corporate power, and structural poverty Edited by Gary Chartier & Charles W. Johnson Individualist anarchists believe in mutual exchange, not economic privilege. They believe in freed markets, not capitalism. They defend a distinctive response to the challenges of ending global capitalism and achieving social justice: eliminate the political privileges that prop up capitalists. Massive concentrations of wealth, rigid economic hierarchies, and unsustainable modes of production are not the results of the market form, but of markets deformed and rigged by a network of state-secured controls and privileges to the business class. Markets Not Capitalism explores the gap between radically freed markets and the capitalist-controlled markets that prevail today. It explains how liberating market exchange from state capitalist privilege can abolish structural poverty, help working people take control over the conditions of their labor, and redistribute wealth and social power. Featuring discussions of socialism, capitalism, markets, ownership, labor struggle, grassroots privatization, intellectual property, health care, racism, sexism, and environmental issues, this unique collection brings together classic essays by Cleyre, and such contemporary innovators as Kevin Carson and Roderick Long. It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism. “We on the left need a good shake to get us thinking, and these arguments for market anarchism do the job in lively and thoughtful fashion.” – Alexander Cockburn, editor and publisher, Counterpunch “Anarchy is not chaos; nor is it violence. This rich and provocative gathering of essays by anarchists past and present imagines society unburdened by state, markets un-warped by capitalism. -

Corporate Impersonation: the Possibilities of Personhood in American Literature, 1886-1917

Corporate Impersonation: The Possibilities of Personhood in American Literature, 1886-1917 by Nicolette Isabel Bruner A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee Professor Gregg D. Crane, Chair Professor Susanna L. Blumenthal, University of Minnesota Professor Jonathan L. Freedman Associate Professor Scott R. Lyons “Everything…that the community chooses to regard as such can become a subject—a potential center—of rights, whether a plant or an animal, a human being or an imagined spirit; and nothing, if the community does not choose to regard it so, will become a subject of rights, whether human being or anything else.” -Alexander Nékám, 1938 © Nicolette Isabel Bruner Olson 2015 For my family – past, present, and future. ii Acknowledgements This dissertation could not have been completed without the support of my committee: Gregg Crane, Jonathan Freedman, Scott Lyons, and Susanna Blumenthal. Gregg Crane has been a constant source of advice and encouragement whose intimate knowledge of law and literature scholarship has been invaluable to my own development as a scholar. Jonathan Freedman’s class on “Fictions of Finance” inspired much of the work in this dissertation, as did Susanna Blumenthal’s seminar on “The Concept of the Person” during my time at the University of Michigan Law School. Jonathan’s good humor, grace, and sympathetic yet critical eye have profoundly shaped my work. As I have expanded my research into animal studies, Scott Lyons guided me to new intellectual domains. Finally, ever since I began working with her during my first year of law school, Susanna has been a source of wisdom, encouragement, and generosity. -

Culturalism Through Public Art Practices

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research John Jay College of Criminal Justice 2011 Assessing (Multi)culturalism through Public Art Practices Anru Lee CUNY John Jay College of Criminal Justice Perng-juh Peter Shyong How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/jj_pubs/49 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 How to Cite: Lee, Anru, and Perng-juh Peter Shyong. 2011. “Assessing (Multi)culturalism through Public Art Practices.” In Tak-Wing Ngo and Hong-zen Wang (eds.) Politics of Difference in Taiwan. Pp. 181-207. London and New York: Routledge. 2 Assessing (Multi)culturalism through Public Art Practices Anru Lee and Perng-juh Peter Shyong This chapter investigates the issue of multiculturalism through public art practices in Taiwan. Specifically, we focus on the public art project of the Mass 14Rapid Transit System in Kaohsiung (hereafter, Kaohsiung MRT), and examine how the discourse of multiculturalism intertwines with the discourse of public art that informs the practice of the latter. Multiculturalism in this case is considered as an ideological embodiment of the politics of difference, wherein our main concern is placed on the ways in which different constituencies in Kaohsiung respond to the political-economic ordering of Kaohsiung in post-Second World War Taiwan and to the challenges Kaohsiung City faces in the recent events engendering global economic change. We see the Kaohsiung MRT public art project as a field of contentions and its public artwork as a ‘device of imagination’ and ‘technique of representation’ (see Ngo and Wang in this volume). -

Download As a PDF File

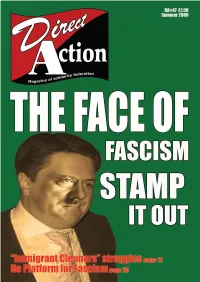

Direct Action www.direct-action.org.uk Summer 2009 Direct Action is published by the Aims of the Solidarity Federation Solidarity Federation, the British section of the International Workers he Solidarity Federation is an organi- isation in all spheres of life that conscious- Association (IWA). Tsation of workers which seeks to ly parallel those of the society we wish to destroy capitalism and the state. create; that is, organisation based on DA is edited & laid out by the DA Col- Capitalism because it exploits, oppresses mutual aid, voluntary cooperation, direct lective & printed by Clydeside Press and kills people, and wrecks the environ- democracy, and opposed to domination ([email protected]). ment for profit worldwide. The state and exploitation in all forms. We are com- Views stated in these pages are not because it can only maintain hierarchy and mitted to building a new society within necessarily those of the Direct privelege for the classes who control it and the shell of the old in both our workplaces Action Collective or the Solidarity their servants; it cannot be used to fight and the wider community. Unless we Federation. the oppression and exploitation that are organise in this way, politicians – some We do not publish contributors’ the consequences of hierarchy and source claiming to be revolutionary – will be able names. Please contact us if you want of privilege. In their place we want a socie- to exploit us for their own ends. to know more. ty based on workers’ self-management, The Solidarity Federation consists of locals solidarity, mutual aid and libertarian com- which support the formation of future rev- munism. -

New to Serbia the Best Entertainment Delta Planet Will Have the Biggest and the Most Prestigious Cinema in the Balkans

The Ultimate Shopping Experience Each day we look for new experiences. To do that, we are building a brand new world – a world made of the best things in this one. Meet the biggest and best-located shopping mall in Delta Planet is designed to be the leading super- Serbia, providing a unique shopping experience for all regional shopping mall, and because of its size, offering, age groups, by offering the largest number of tenants and convenient location, it will attract visitors from the and a wide variety of international and local fashion city, the whole country, and also from across the region. brands. Delta Planet will change the face of Belgrade and Around 5,000 workers from many local companies become a symbol for a new quality of life. will be engaged in the construction of the mall. Its completion will create over 5,000 new jobs. The 182,000 m² shopping mall will be located at Autokomanda, Belgrade, near the E-75 highway, in the According to the plan, Delta Planet will offer 250 stores direction of Nis, with construction scheduled to start in with various contents to visitors in autumn 2014. the autumn of 2013. Its excellent position, close to the center of Belgrade and only 20 minutes from the airport, will facilitate access to visitors from the whole region. This EUR 200 million project will not only be the largest investment by the Delta Real Estate Group in the coming period, but will also be the second largest real estate investment in Serbia since 2000. City Landmark Spectacular Architecture The architecture of the mall is highlighted by its Looking to the future and the need to create a innovative design and use of the latest technology, sustainable “blue” planet, we are creating the first completely adapted to its surroundings. -

On Social Ecology and Climate Justice

For Stefan G. Jacobsen, ed., Climate Justice and the Economy: Social mobilization, knowledge and the political (Routledge 2018) On Social Ecology and the Movement for Climate Justice – Brian Tokar, Institute for Social Ecology and University of Vermont Environmental Program Abstract: The theory and praxis of social ecology have guided social movements seeking a radical, counter- systemic ecological outlook since the 1960s, advancing goals of transforming society’s relationship to non-human nature and reharmonizing human communities’ ties to the natural world. This chapter reviews the philosophy and political outlook of social ecology, its multifaceted contributions to social movements past and present, and its emerging contributions to addressing current climate policy challenges. These include the viability of proposed transition strategies toward a fossil-free future, the potentialities and limitations of localist, community-centered responses to climate change, the problems inherent in current market-driven models of renewable energy development, and the potential contributions of reconstructive, neo-utopian outlooks to contemporary climate politics. We conclude that, despite the ever-present threat of climate catastrophe, a genuinely transformative climate justice movement needs to advance a forward-looking view of an improved quality of life for most people in a future freed from fossil fuel dependence. As the immediate consequences of global climate disruptions become increasingly difficult to ignore, a host of long-range, systemic -

'Diversity' in the Natural Law of Our Time Gines Marco Catholic University of Valencia, [email protected]

Journal of Vincentian Social Action Volume 3 Article 8 Issue 2 Journal of Vincentian Social Action November 2018 The mpI act of the Concepts of 'Common Good', 'Justice' and 'Diversity' in the Natural Law of our Time Gines Marco Catholic University of Valencia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.stjohns.edu/jovsa Part of the Applied Ethics Commons, Business Commons, Law Commons, and the Other Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Marco, Gines (2018) "The mpI act of the Concepts of 'Common Good', 'Justice' and 'Diversity' in the Natural Law of our Time," Journal of Vincentian Social Action: Vol. 3 : Iss. 2 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholar.stjohns.edu/jovsa/vol3/iss2/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by St. John's Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Vincentian Social Action by an authorized editor of St. John's Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE IMPACT OF THE CONCEPTS OF ‘COMMON GOOD’, ‘JUSTICE’ AND ‘DIVERSITY’ IN THE NATURAL LAW OF OUR TIME Ginés Marco1 1. THE ETHICAL NATURE OF SOCIAL LIFE realize the social nature of man and, to that extent, contribute to manifesting what it is to be human. an is, by nature, a social being. The Now, family and city contribute -better or worse- Mexperience that the human being tends to to that end, to the extent that they promote or society and needs it to live humanly is so clear and not human development, according to the goods permanent that it does not take a great speculative that - following St.