From the Park to Parking: the Evolution of Suburban Mobility

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Village in the City Historic Markers Lead You To: Mount Pleasant Heritage Trail – a Pre-Civil War Country Estate

On this self-guided walking tour of Mount Pleasant, Village in the City historic markers lead you to: MOUNT PLEASANT HERITAGE TRAIL – A pre-Civil War country estate. – Homes of musicians Jimmy Dean, Bo Diddley and Charlie Waller. – Senators pitcher Walter Johnson's elegant apartment house. – The church where civil rights activist H. Rap Brown spoke in 1967. – Mount Pleasant's first bodega. – Graceful mansions. – The first African American church on 16th Street. – The path President Teddy Roosevelt took to skinny-dip in Rock Creek Park. Originally a bucolic country village, Mount Pleasant has been a fashion- able streetcar suburb, working-class and immigrant neighborhood, Latino barrio, and hub of arts and activism. Follow this trail to discover the traces left by each succeeding generation and how they add up to an urban place that still feels like a village. Welcome. Visitors to Washington, DC flock to the National Mall, where grand monuments symbolize the nation’s highest ideals. This self-guided walking tour is the seventh in a series that invites you to discover what lies beyond the monuments: Washington’s historic neighborhoods. Founded just after the Civil War, bucolic Mount Pleasant village was home to some of the city’s movers and shakers. Then, as the city grew around it, the village evolved by turn into a fashionable streetcar suburb, a working-class neigh- borhood, a haven for immigrants fleeing political turmoil, a sometimes gritty inner-city area, and the heart of DC’s Latino community. This guide, summariz- ing the 17 signs of Village in the City: Mount Pleasant Heritage Trail, leads you to the sites where history lives. -

Hillcrest: the History and Architectural Heritage of Little Rock's Streetcar Suburb

Hillcrest: The History and Architectural Heritage of Little Rock's Streetcar Suburb By Cheryl Griffith Nichols and Sandra Taylor Smith Butterworth House Hillcrest Historic District Little Rock, Arkansas Published by the Arkansas Historic Preservation Program 1500 Tower Building, 323 Center Street, Little Rock, AR 72201 (501) 324-9880 An agency of the Department of Arkansas Heritage 1 Hillcrest: The History and Architectural Heritage of Little Rock's Streetcar Suburb A Historic Context Written and Researched By Cheryl Griffith Nichols and Sandra Taylor Smith Cover illustration by Cynthia Haas This volume is one of a series developed by the Arkansas Historic Preservation Program for the identification and registration of the state's cultural resources. For more information, write the AHPP at 1500 Tower Building, 323 Center Street, Little Rock, AR 72201, call (501) 324-9880 [TDD 501-324-9811], or send e-mail to [email protected] The Arkansas Historic Preservation Program is the agency of the Department of Arkansas Heritage responsible for the identification, evaluation, registration and preservation of the state's cultural resources. Other agencies in the department are the Arkansas Arts Council, the Delta Cultural Center, the Old State House Museum, Historic Arkansas Museum, the Arkansas Natural Heritage Commission, and the Mosaic Templars Cultural Center. 2 Contents Hillcrest Significance ............................................................................................ 5 Origins of Pulaski Heights ........................................................................... -

Transit-Oriented Development and Active

FOCUS 12 Essays Shifting the Tide: Transit-Oriented Development and Active Transportation Planning in Los Angeles Forrest Chamberlain William Riggs MCRP , Cal Pol an uis bispo Ph ssistant Professor, CRP epartment, Cal Pol an uis bispo Chamberlain and Riggs present an overview of the historical context of automobile dependency in Los Angeles, the current transit-oriented development strategies underway, and the planning and implementation of Complete Street strategies. The discussion illustrates how the city is using these strategies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and the impacts of climate change. os Angeles has the reputation of an auto dependent city. the urban form of Los Angeles. Before the private automobile LHistorically, much of the region was developed as suburban gained popularity, Los Angeles was served by an extensive sprawl, designed to accommodate automobile use. Although streetcar system, established in the late 1800s by powerful real the region is served by a robust public transportation system, estate moguls. These entrepreneurs not only constructed the the majority of the population commutes by automobile streetcar lines themselves, but also residential neighborhoods (SCAG, 2012a). As a result of excessive automobile use, adjacent to streetcar lines (Jackson, 1985). The streetcar the region has long suered from poor air quality, trac system thus enabled Los Angeles to grow outward from the congestion, unsafe streets, and environmental degradation. downtown core, fostering the development of “streetcar Sprawling development patterns have diminished the suburbs” that would eventually set the momentum for the environmental quality of natural areas on the urban fringe. region’s decentralization and sprawl (Bottles, 1987; Jackson, Automobile use has exacerbated the region’s greenhouse 1985; Longstreth, 1998). -

Pre-Consolidation Communities of Los Angeles, 1862-1932

LOS ANGELES CITYWIDE HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT Context: Pre-Consolidation Communities of Los Angeles, 1862-1932 Prepared for: City of Los Angeles Department of City Planning Office of Historic Resources July 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 1 CONTRIBUTOR 1 INTRODUCTION 1 THEME: WILMINGTON, 1862-1909 4 THEME: SAN PEDRO, 1882-1909 30 THEME: HOLLYWOOD, 1887-1910 56 THEME: SAWTELLE, 1896-1918 82 THEME: EAGLE ROCK, 1886-1923 108 THEME: HYDE PARK, 1887-1923 135 THEME: VENICE, 1901-1925 150 THEME: WATTS, 1902-1926 179 THEME: BARNES CITY, 1919-1926 202 THEME: TUJUNGA, 1888-1932 206 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPY 232 SurveyLA Citywide Historic Context Statement Pre-consolidation Communities of Los Angeles, 1862-1932 PREFACE This historic context is a component of Los Angeles’ citywide historic context statement and provides guidance to field surveyors in identifying and evaluating potential historic resources relating to Pre- Consolidation Communities of Los Angeles. Refer to www.HistoricPlacesLA.org for information on designated resources associated with this context as well as those identified through SurveyLA and other surveys. CONTRIBUTOR Daniel Prosser is a historian and preservation architect. He holds an M.Arch. from Ohio State University and a Ph.D. in history from Northwestern University. Before retiring, Prosser was the Historic Sites Architect for the Kansas State Historical Society. INTRODUCTION The “Pre-Consolidation Communities of Los Angeles” context examines those communities that were at one time independent, self-governing cities. These include (presented here as themes): Wilmington, San Pedro, Hollywood, Sawtelle, Eagle Rock, Hyde Park, Venice, Watts, Barnes City, and Tujunga. This context traces the history of each of these cities (up to the point of consolidation with the City of Los Angeles), identifying important individuals and patterns of settlement and development, and then links the events and individuals to extant historic resources (individual resources and historic districts). -

Housing Issues & Opportunities (PDF)

HOUSING Credit: Jennifer Lutke Credit: Jennifer Lutke Credit: Jennifer Lutke INTRODUCTION Over the past 300 years, Brookline has evolved from an agricultural community and streetcar suburb to an incredibly diverse community that provides a wide-range of housing types and lifestyle choices from the mixed use, transit-oriented neighborhoods near Coolidge Corner, Brookline Village, and Washington Square to the suburban neighborhoods of South Brookline. Brookline offers a high quality of life to its residents. This report explores the current state of housing in This, in combination with its close proximity and Brookline and defines preliminary issues and oppor- transit connections to Boston and Cambridge, creates tunities related to our housing stock, policies, and an exceptionally desirable community to live in. programs. The report also provides a brief back- Brookline, which consists of roughly six square miles ground on housing in Brookline to foster an under- of land, is home to approximately 54,700 people of standing of where we have come from, in terms of diverse backgrounds, incomes, and lifestyles, includ- evolution of overall development, as well as the vari- ing families, young professionals,and elderly. ous programs and regulations related to housing. Background of Brookline Housing Development Brookline, which began as an agricultural community for veterans after World War II. As the BHA contin- in the 17th century, became a streetcar suburb of ued to develop housing, it added developments tar- Boston during the mid-19th century. At this time, geted to elderly housing to the mix. Brookline’s development opportunities were enhanced by the provision of strong public transit From the late 1950s to the 70s, Brookline engaged in with direct linkages to Boston. -

Cannon Streetcar Suburb District Nomination

DRAFT 07-21-2020 Spokane Register of Historic Places Nomination Spokane City/County Historic Preservation Office, City Hall, Third Floor 808 Spokane Falls Boulevard, Spokane, Washington 99201-3337 1. Name of Property Historic Name: Cannon’s Addition And/Or Common Name: Cannon Streetcar Suburb Historic District 2. Location Street & Number: Various City, State, Zip Code: Spokane, WA 99204 Parcel Number: Various 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use ☐building ☐public ☒both ☒occupied ☐agricultural ☐museum ☐site ☐private ☐work in progress ☒commercial ☐park ☐structure ☐educational ☒residential ☐object Public Acquisition Accessible ☐entertainment ☐religious ☒district ☐in process ☐yes, restricted ☐government ☐scientific ☐being considered ☒yes, unrestricted ☐industrial ☐transportation ☐no ☐military ☒other 4. Owner of Property Name: Various Street & Number: n/a City, State, Zip Code: n/a Telephone Number/E-mail: n/a 5. Location of Legal Description Courthouse, Registry of Deeds Spokane County Courthouse Street Number: 1116 West Broadway City, State, Zip Code: Spokane, WA 99260 County: Spokane 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Title: Ninth Avenue National Register Historic District Date: Enter survey date if applicable ☒Federal ☐State ☐County ☐Local Depository for Survey Records: Spokane Historic Preservation Office 7. Description Architectural Classification Condition Check One ☐excellent ☐unaltered ☒good ☒altered ☐fair ☐deteriorated Check One ☐ruins ☒original site ☐unexposed ☐moved & date ______________ Narrative statement of description is found on one or more continuation sheets. 8. Spokane Register Categories and Statement of Significance Applicable Spokane Register of Historic Places category: Mark “x” on one or more for the categories that qualify the property for the Spokane Register listing: ☒A Property is associated with events that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of Spokane history. -

4100 Haverford Ave, West Philadelphia Passenger Railway Company Carhouse

COMMENT ON NATIONAL REGISTER NOMINATION ADDRESS: 4100 Haverford Ave, West Philadelphia Passenger Railway Company Carhouse OVERVIEW: The Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission (PHMC) has requested comments from the Philadelphia Historical Commission on the National Register nomination of 4100 Haverford Avenue located in the Haverford North neighborhood of West Philadelphia and historically known as the West Philadelphia Passenger Railway Company Carhouse. PHMC is charged with implementing federal historic preservation regulations in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, including overseeing the National Register of Historic Places in the state. PHMC reviews all such nominations before forwarding them to the National Park Service for action. As part of the process, PHMC must solicit comments on every National Register nomination from the appropriate local government. The Philadelphia Historical Commission speaks on behalf of the City of Philadelphia in historic preservation matters including the review of National Register nominations. Under federal regulation, the local government not only must provide comments, but must also provide a forum for public comment on nominations. Such a forum is provided during the Philadelphia Historical Commission’s meetings. According to the nomination, the West Philadelphia Passenger Railway Company Carhouse is significant under Criterion A in the Area of Transportation. Following the annexation of 130 square miles into the City of Philadelphia in 1854, growth of areas outside of the city’s original boundaries was largely due to the streetcar industry. The West Philadelphia Passenger Railway Company (WPPRC) was established in 1858 following the completion of a rail line along Market Street that ran from 3rd Street in Center City to 41st Street in West Philadelphia. -

A Streetcar Suburb for the 21St Century: Transit-Supportive Design

A Streetcar Suburb for the 21st Century: Transit-Supportive Design Guidelines & Policy Recommendations for Eglinton Avenue West in Toronto By Brian Anders A report submitted to the School of Urban & Regional Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Urban & Regional Planning (M.Pl) Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario Copyright © Brian Anders, 2012 Executive Summary This report seeks to develop a series of urban design guidelines and policy looked at and analyzed for strengths, weakness, opportunities and constraints. recommendations along a 4-kilometre segment of Eglinton Avenue West between Two Case Studies of successful transit-oriented development, Collingwood Martin Grove and Scarlett Roads in Toronto, Ontario (The ‘Study Area,’ See figure Village in Vancouver, BC, and Orenco Station near Portland, OR were considered and below) to foster transit usage over a span of roughly 20 years in anticipation of compared using a number of secondary sources. a future at-grade light rail transit (LRT) line, the Eglinton Crosstown, expected to Urban design guidelines and recommendations for policy changes commence operations by 2030. to promote a more transit- and pedestrian-oriented built form within the Study Area were then formulated using the lessons learned from the Case Studies. Study Method & Structure of the Report: An evaluation of these guidelines and recommendations was then done Qualitative methods are employed throughout this report, which is using qualitative indicators contained in a ‘Transit Oriented Development Index’ organized as follows: developed by the US Transportation Research Board’s Transit Cooperative Research A Study Area analysis, conducted using urbanist Kevin Lynch’s 1984 work Program (TCRP). -

Lettersize Brochure Recreated

Architecture in the Cleveland Park Historic District What is now Cleveland Park example in the neighBorhood of a house designed to MODERN HOUSES began in the 18th century as be a summer home. The architecture of Cleveland Park has continued to a single estate of nearly 1000 Tregaron, 3100 Macomb Street: Tregaron was Built evolve, with houses By several notaBle 20th-century acres. It was divided into in 1912 for arts patron James Parmalee and was architects. Arround the west end of Rosedale on smaller estates after the Civil purchased in 1941 by Joseph Davies and his wife Ordway and 36th Streets are several houses designed War, when the area served as Marjorie Merriweather Post. The estate has Been the By the Faulkner family of architects Between 1937 and a fashionable summer escape from downtown home of the Washington International School since the 1970s. 3415 and 3419 36th Street are by Waldron Washington. It was developed as a streetcar suburb 1980. The Tregaron Conservancy is working to restore Faulkner and date from the 1930s. 3530 and 3540 beginning in the 1890s, when trolley lines were the property. See TregaronConservancy.org for more Ordway Street and 3403, 3407, and 3411 36th Street extended over Rock Creek Park. Thanks to the information. were built by his son, Winthrop Faulkner, in the stewardship of many individual owners, institutions, 1960s and ‘70s. A 1962 house by I.M. Pei is at 3411 The Homestead (“La Quinta”), 2700 Macomb Street: conservancies, and the Cleveland Park Historical Ordway Street. Society, the neighborhood today retains the legacy of Designed in 1914 By architect Frederick Pyle, the APARTMENT HOUSES all of these periods of development in its architecture house was much enlarged and remodeled By its and landscapes. -

Enhanced Transit Services Briefing Report

The Potential for Enhanced Transit Services in the City of Burlington: Briefing Report Final Report May 2011 Summary and Contents 1) The City of Burlington once had an extensive streetcar system. (p. 2-4) 2) Past transit studies in The City of Burlington and Chittenden County are somewhat inconsistent – both in technologies studied and in proposed routes. None have focused on streetcars. (p. 5-7) 3) There is a resurgence of streetcars in the U.S. as “Development-Oriented Transit.” The most successful projects have catalyzed mixed use land development at higher densities than would otherwise have been achieved. (p. 8-11) 4) The highest potential for Development-Oriented Transit in combination with extensive redevelopment is in Burlington’s south end with connections to the waterfront, the downtown, UVM and FAHC. (p. 12-15) 5) Streetcars are less expensive and less intrusive than Light Rail Transit (LRT), but more expensive and less flexible than expanding bus service and/or Bus Rapid Transit (BRT). A 6-mile streetcar loop in Burlington would likely cost $60 - $100 million. A BRT system with similar amenities would cost less, perhaps half as much. Expansion of conventional bus service could be improved significantly with little capital cost beyond the cost of additional buses. (p. 16-20) 6) The highest ridership and regional environmental benefits would be achieved through development with a significant housing component in the south end. (p. 21-23) Prepared for the City of Burlington Department of Public Works by Smart Mobility, Inc., Oman Analytics, and the ORW Architects and Planners. Smart Mobility, ORW and Oman Analytics 1 Briefing Report: The Potential for Enhanced Transit Service in Burlington History of Streetcars in Burlington The City of Burlington once had an extensive streetcar network. -

Historic Residential Suburbs

National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER BULLETIN U.S. Department of the Interior HISTORIC RESIDENTIAL SUBURBS GUIDELINES FOR EVALUATION AND DOCUMENTATION FOR THE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES -( CITY OF PORTLAND I r Pi ri II i m t ' I i J , I i. I J I * ' l_. JJ_ 1_J L I i_ J 1 - - M-A- W -T- H-0 -R-N-C - -" ' '"*»-J •••• -••*«•"-" 4 -^-j. A-V-E-N-U-E- - - NATIONAL REGISTER BULLETIN HISTORIC RESIDENTIAL SUBURBS GUIDELINES FOR EVALUATION AND DOCUMENTATION FOR THE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES David L. Ames, University of Delaware Linda Flint McClelland, National Park Service September 2002 U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, National Register of Historic Places Mission of the National Park Service The National Park Service preserves unimpaired the natural and cultural resources and the values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education and inspiration of this and future generations. The Park Service cooperates with partners to extend the benefits of natural and cultural resource con- servation and outdoor recreation through- out this country and the world. Above: Monte Vista School (1931), Albuquerque, New Mexico. In keeping with formal Beaux Arts principles of planning, the Spanish Colonial Revival school was designed as an architectural landmark marking the entrance to the Monte Vista and College View neighborhoods. (Photo by Kathleen Brooker, courtesy New Mexico Office of Cultural Affairs) Inside front cover and title page: Plat (c. 1892) and Aerial View (1920), Ladd's Addition, Portland, Oregon. Platted as a streetcar suburb at the beginning of the City Beautiful movement, Ladd's Addition represents one of the earliest documented cases of a garden suburb with a complex, radial plan. -

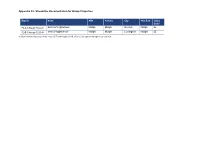

Appendix F2- Streamline Documentation for Group Properties

Appendix F2- Streamline Documentation for Group Properties Map ID Name APN Address City Year Built Status Code* F2-A-1 through F2-A-20 Gardena Neighborhood Multiple Multiple Glendale Multiple 6Z F2-B-1 through F2-B-48 Seneca Neighborhood Multiple Multiple Los Angeles Multiple 6Z *California Historical Resources Status Codes: 6Z: Found ineligible for NR, CR or Local designation through survey evaluation. Appendix F2: Streamlined Documentation (Group) Gardena Avenue Neighborhood Cover Sheet MR Number: F2-A-1 through F2-A-20 APN: Multiple, see attached matrix City: Glendale Address: Multiple, see attached matrix Year built: Multiple, see attached matrix Context: Residential Development Alterations: The Gardena Avenue neighborhood is an example of a residential tract developed as a part of a streetcar suburb. It consists primarily of modest single family residences in the Craftsman style, constructed during the 1910s and 1920s. Infill development includes a few single family residences constructed in the 1930s through 1950s, and a number of two to three-story multifamily residential buildings constructed in the 1960s. The multifamily buildings are visually prominent within the neighborhood and out of scale with the smaller single family residences. The Craftsman cottages that do remain in the neighborhood have been altered over time, most commonly with changes to the exterior cladding, and the replacement and resizing of windows and doors. These alterations have diminished the integrity of the individual resources such that they no longer reflect their historic identity as 1910s- 1920s Craftsman bungalows. As a result of cumulative changes to the neighborhood, including diminished integrity of the individual buildings and the residential blocks as a whole, it no longer reflects its historic identity as a streetcar suburb.