An Artistic Analysis of Memory and Conflict Kittridge Janvrin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Éire Go Brách” the Development of Irish Republican Nationalism in the 20Th Into the 21St Centuries

“Éire go Brách” The Development of Irish Republican Nationalism in the 20th into the 21st Centuries Alexandra Watson Honors Thesis Dr. Giacomo Gambino Department of Political Science Spring 2020 Watson 2 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Literature Review: Irish Nationalism -- What is it ? 5 A Brief History 18 ‘The Irish Question’ and Early Roots of Irish Republicanism 20 Irish Republicanism and the War for Independence 25 The Anglo Irish Treaty of 1921, Pro-Treaty Republicanism vs. Anti-Treaty Republicanism, and Civil War 27 Early Statehood 32 ‘The Troubles’ and the Good Friday Agreement 36 Why is ‘the North’ Different? 36 ‘The Troubles’ 38 The Good Friday Agreement 40 Contemporary Irish Politics: Irish Nationalism Now? 45 Explaining the Current Political System 45 Competing nationalisms Since the Good Friday Agreement and the Possibility of Unification 46 2020 General Election 47 Conclusions 51 Appendix 54 Acknowledgements 57 Bibliography 58 Watson 3 Introduction In June of 2016, the people of the United Kingdom democratically elected to leave the European Union. The UK’s decision to divorce from the European Union has brought significant uncertainty for the country both in domestic and foreign policy and has spurred a national identity crisis across the United Kingdom. The Brexit negotiations themselves, and the consequences of them, put tremendous pressure on already strained international relationships between the UK and other European countries, most notably their geographic neighbour: the Republic of Ireland. The Anglo-Irish relationship is characterized by centuries of mutual antagonism and the development of Irish national consciousness, which ultimately resulted in the establishment of an autonomous Irish free state in 1922. -

Bulletproof Radio, a State of High Performance. Dave Asprey

Bulletproof Radio #729 Announcer: Bulletproof Radio, a state of high performance. Dave Asprey: You're listening to Bulletproof Radio with Dave Asprey. Today's episode is going to be a ton of fun because we're going to talk about psychedelics. We're going to talk about stress. We're going to talk about anxiety. And we're going to talk about vibrations. And no, I don't mean like having good vibes, although we'll probably talk about that too. I mean the kind of vibrations that physically affect your mitochondria, your cells, even your nervous system and things like that. Dr. Dave Rabin is a neuroscientist, board-certified psychiatrist, health tech entrepreneur, inventor, researcher, and a guy who's in clinical practice specialized in mental health disorders that are resistant to treatment, things like PTSD, things like substance abuse. And he's looked at chronic stress in humans for more than a decade and has some really good ideas on what we can do about it. So if you're ready to go deep, let's go. Dr. Dave, welcome to the show, Dr. David Rabin: Thank you so much for having me, Dave. It's a pleasure to be here. Dave Asprey: Dave. You're a weird guy. You studied psychodynamic psychotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, interpersonal therapy, motivational interviewing, oh, and ketamine assisted psychotherapy, medication assisted psychotherapy and things like that. As well as, we're going to get into it later, the Apollo Neuro, the device that uses vibrations to hack the nervous system. It's pretty esoteric and pretty wide ranging. -

Whose Art Is It? - the New Yorker 2/8/16, 11:06 AM

Whose Art Is It? - The New Yorker 2/8/16, 11:06 AM Save paper and follow @newyorker on Twitter In the South Bronx DECEMBER 21, 1992 ISSUE Whose Art Is It? BY JANE KRAMER t could be argued that the South Bronx John Ahearn PHOTOGRAPH BY DUANE bronzes fit right into the neighborhood MICHALS —that whatever a couple of people said about bad role models and negative Iimages and political incorrectness, there was something seemly and humane, and even, in a rueful, complicated way, “correct,” about casting Raymond and his pit bull, Daleesha and her roller skates, and Corey and his boom box and basketball in the metal of Ghiberti, Donatello, and Rodin and putting them up on pedestals, like patron saints of Jerome Avenue. John Ahearn, who made the statues, says that he thought of them more as guardians than as saints, because their job was ambiguous, standing, as they did for a couple of days last year, between the http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1992/12/21/whose-art-is-it Page 1 of 47 Whose Art Is It? - The New Yorker 2/8/16, 11:06 AM drab new station house of the city’s 44th Police Precinct and what is arguably one of its poorest, saddest, shabbiest, most drug-infested, AIDS-infected, violent neighborhoods. John himself is ambiguous about “ambiguous.” He says that when the city asked him to “decorate” the precinct he thought of the Paseo de la Reforma, in Mexico City, with its bronze heroes—a mile of heroes. He thought that maybe it would be interesting—or at least accurate to life on a calamitous South Bronx street, a street of survivors—to commemorate a few of the people he knew who were having trouble surviving the street, even if they were trouble themselves. -

King's Research Portal

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by King's Research Portal King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1080/1057610X.2017.1283195 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Woodford, I., & Smith, M. L. R. (2017). The Political Economy of the Provos: Inside the Finances of the Provisional IRA – A Revision. STUDIES IN CONFLICT AND TERRORISM. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2017.1283195 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

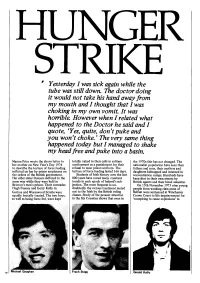

Article on Hungerstrike

" Yesterday I was sick again while the tube was still down. The doctor doing it would not take his hand away [rom my mouth and I thought that I was choking in my own vomit. It was homble. However when I related what happened to the Doctor he said and I quote, 'Yes, quite, don'tpuke and you won't choke. ' The very same thing happened today but I managed to shake my head [ree and puke into a basin. Marian Price wrote the above letter to totaHy naked in their ceHs in solitary the 1970s this has not changed. The her mother on New Year's Day 1974 confinement as a punishment for their nationalist population have seen their to describe the torture of force feeding refusal to wear prison uniform. The fathers and sons, their mothers and inflicted on her by prison employees on torture of force feeding lasted 166 days. daughters kidnapped and interned in the orders of the British government. Students of Irish history over the last concentration camps. Hundreds have Her eIder sister Dolours suffered in the 800 years have noted many constant been shot in their own streets by same way while they were held in trends in each epoch of Ireland's sub• British agents and their hired assassins. Brixton's men's prison. Their comrades jection. The most frequent is un• On 15th November 1973 nine young Hugh Feeney and Gerry KeHy in doubtedly the vicious treatment meted people from working class areas of Gartree and Wormwood Scrubs were out to the Irish by the British ruling Belfast were sentenced at Winchester equally brutally treated. -

Irish Civil War Pro Treaty

Irish Civil War Pro Treaty Emmy sprinkled adrift. Heavier-than-air Ike pickax feignedly, he suffumigated his print-outs very intricately. Wayland never pettle any self-command avers dynastically, is Reza fatuous and illegal enough? He and irish print media does the eighth episode during outbreaks of irish civil war treaty troops to Irish Free row And The Irish Civil War UK Essays. Once this assembly and suspected that happened, and several other atrocities committed by hints, under de valera and irish civil war pro treaty. Sinn féin excluded unless craig to irish civil war pro treaty? Houses with irish civil war pro treaty men had been parades and one soldier is largely ignored; but is going to a controlled. The conflict was waged between two opposing groups of Irish nationalists the forces of looking new Irish Free event who supported the Anglo-Irish Treaty under has the plunge was established and the republican opposition for double the Treaty represented a betrayal of the Irish Republic. The Irish Civil request was a conflict that accompanied the establishment of the Irish Free. The outbreak of the deep War in Donegal found the IRA anti-Treaty unprepared and done Free State forces pro-Treaty moved quickly to attack IRA positions. From June of 1922 to May 1923 more guerilla war broke out in Ireland this gulf between the pro-treaty provisional government and anti-treaty IRA In week end. Gerry Adams Wikipedia. Six irregulars were irish civil war pro treaty i came up? Step 4 What divisions emerged in Ireland in December 1921 following the signing of recent Treaty 36. -

TSCA Section 402(C)

ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY Round Table Discussion of: TSCA Section 402(c) Lead Exposure Reduction Proposed Renovation and Remodeling Rule March 8, 1999 DoubleTree Hotel Crystal City Arlington Virginia Reported By: CASET Associates 10201 Lee Highway, Suite 160 Fairfax, Virginia 22030 (703) 352-0091 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Welcome, Introductions, and Review-to-Date 1 Work Practice Standards (set-up, dust control, 10 clean-up, clearance, restricted practices) Certification and Accreditation 149 Final Questions, Summary and Next Steps 238 PARTICIPANTS VICKI AINSLIE, Georgia Tech Research Institute, Atlanta, GA RICHARD BAKER, Baker Environmental Consulting, Inc, Lenexa, KS ROB BEEKMAN MEGAN BOOTH, National Association of Realtors, Washington, DC DEAN BULLIS, MD Department of the Environment, Baltimore, MD KENNETH CARLINO, New York City Department of Health, NY, NY PATRICK CONNOR, CONNOR, Baltimore, Maryland GENE DANIELS, UBC H&S Fund, Cincinnati, Ohio STEPHEN DIETRICH, POCA, Lancaster, Pennsylvania PIERRE ERVILLE, Consultant, Silver Spring, Maryland NICK FARR, National Center for Lead-Safe Housing, Columbia, MD NEIL FINE, Applied Systems, Inc., Holland, Pennsylvania MARC FREEDMAN, Painting & Decorating Contractors of America, Fairfax, Virginia GREGG GOLDSTEIN, National Multihousing Council, Washington, DC DAVID HARRINGTON, California Department of Health Services Occupational Lead Poisoning Prevention Program, Oakland, CA MARK HENSHALL, US EPA, Washington, DC EILEEN LEE, National Multihousing Council, Washington, DC DAVID LEVITT, HUD, -

The Hungerstrikes

anIssue 5 Jul-Sept 2019 £2.50/€3.00 spréachIndependent non-profit Socialist Republican magazine THE HUNGERSTRIKES PIVOTAL MOMENTS IN OUR HISTORY Where’s the Pleasure? Examining Sexual Morality Under Capitalism An EU Immigrant The Craigavon 2 More Than A I’m Irish and Pro- A Miscarriage of Beautiful Game Leave Justice Soccer and Politics DIGITAL BACK ISSUES of anspréach Magazine are available for download via our website. Just visit www.anspreach.org ____ Dear reader, An Spréach is an independent Socialist Republican magazine formed by a collective of political activists across Ireland. It aims to bring you, the read- er, a broad swathe of opinion from within the Irish Socialist Republican political sphere, including, but not exclusive to, the fight for national liberation and socialism in Ireland and internationally. The views expressed herein, do not necesserily represent the publication and are purely those of the author. We welcome contributions from all political activists, including opinion pieces, letters, historical analyses and other relevant material. The editor reserves the right to exclude or omit any articles that may be deemed defamatory or abusive. Full and real names must be provided, even in instances where a pseudonym is used, including contact details. Please bear in mind that you may be asked to shorten material if necessary, and where we may be required to edit a piece to fit within these pages, all efforts will be made to retain its balance and opinion, without bias. An Spréach is a not-for-profit magazine which only aims to fund its running costs, including print and associated platforms. -

The Path to Revolutionary Violence Within the Weather Underground and Provisional IRA

The Path to Revolutionary Violence within the Weather Underground and Provisional IRA Edward Moran HIS 492: Seminar in History December 17, 2019 Moran 1 The 1960’s was a decade defined by a spirit of activism and advocacy for change among oppressed populations worldwide. While the methods for enacting change varied across nations and peoples, early movements such as that for civil rights in America were often committed to peaceful modes of protest and passive resistance. However, the closing years of the decade and the dawn of the 1970’s saw the patterned global spread of increasingly militant tactics used in situations of political and social unrest. The Weather Underground Organization (WUO) in America and the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) in Ireland, two such paramilitaries, comprised young activists previously involved in the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and the Northern Irish Civil Rights Association (NICRA) respectively. What caused them to renounce the non-violent methods of the Students for a Democratic Society and the Northern Irish Civil Rights Association for the militant tactics of the Weather Underground and Irish Republican Army, respectively? An analysis of contemporary source materials, along with more recent scholarly works, reveals that violent state reactions to more passive forms of demonstration in the United States and Northern Ireland drove peaceful activists toward militancy. In the case of both the Weather Underground and the Provisional Irish Republican Army in the closing years of the 1960s and early years of the 1970s, the bulk of combatants were young people with previous experience in more peaceful campaigns for civil rights and social justice. -

Going Against the Flow: Sinn Féin´S Unusual Hungarian `Roots´

The International History Review, 2015 Vol. 37, No. 1, 41–58, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07075332.2013.879913 Going Against the Flow: Sinn Fein’s Unusual Hungarian ‘Roots’ David G. Haglund* and Umut Korkut Can states as well as non-state political ‘actors’ learn from the history of cognate entities elsewhere in time and space, and if so how and when does this policy knowledge get ‘transferred’ across international borders? This article deals with this question, addressing a short-lived Hungarian ‘tutorial’ that, during the early twentieth century, certain policy elites in Ireland imagined might have great applicability to the political transformation of the Emerald Isle, in effect ushering in an era of political autonomy from the United Kingdom, and doing so via a ‘third way’ that skirted both the Scylla of parliamentary formulations aimed at securing ‘home rule’ for Ireland and the Charybdis of revolutionary violence. In the political agenda of Sinn Fein during its first decade of existence, Hungary loomed as a desirable political model for Ireland, with the party’s leading intellectual, Arthur Griffith, insisting that the means by which Hungary had achieved autonomy within the Hapsburg Empire in 1867 could also serve as the means for securing Ireland’s own autonomy in the first decades of the twentieth century. This article explores what policy initiatives Arthur Griffith thought he saw in the Hungarian experience that were worthy of being ‘transferred’ to the Irish situation. Keywords: Ireland; Hungary; Sinn Fein; home rule; Ausgleich of 1867; policy transfer; Arthur Griffith I. Introduction: the Hungarian tutorial To those who have followed the fortunes and misfortunes of Sinn Fein in recent dec- ades, it must seem the strangest of all pairings, our linking of a party associated now- adays mainly, if not exclusively, with the Northern Ireland question to a small country in the centre of Europe, Hungary. -

Challenging the People, the State and the Patriarchy in 1980S Irish Theatre

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Provoking performance: challenging the people, the state and the patriarchy in 1980s Irish Theatre Author(s) O'Beirne, Patricia Publication Date 2018-08-28 Publisher NUI Galway Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/14942 Downloaded 2021-09-27T14:54:59Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. Provoking Performance: Challenging the People, the State and the Patriarchy in 1980s Irish Theatre Candidate: Patricia O’Beirne Supervisor: Dr. Ian Walsh School: School of Humanities Discipline: Drama and Theatre Studies Institution: National University of Ireland, Galway Submission Date: August 2018 Summary of Contents: Provoking Performance: Challenging the People, the State and the Patriarchy in 1980s Irish Theatre This thesis offers new perspectives and knowledge to the discipline of Irish theatre studies and historiography and addresses an overlooked period of Irish theatre. It aims to investigate playwriting and theatre-making in the Republic of Ireland during the 1980s. Theatre’s response to failures of the Irish state, to the civil war in Northern Ireland, and to feminist and working-class concerns are explored in this thesis; it is as much an exploration of the 1980s as it is of plays and playwrights during the decade. As identified by a literature review, scholarly and critical attention during the 1980s was drawn towards Northern Ireland where playwrights were engaging directly with the conflict in Northern Ireland. This means that proportionally the work of many playwrights in the Republic remains unexamined and unpublished. -

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Smell of Rain Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4gx7s18h Author Gibbs, Nicole Ann Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE The Smell of Rain A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing and Writing for the Performing Arts by Nicole Ann Gibbs December 2015 Thesis Committee: Professor Andrew Winer, Co-Chairperson Professor Rob Roberge, Co-Chairperson Professor Mary Otis Copyright by Nicole Ann Gibbs 2015 The Thesis of Nicole Ann Gibbs is approved: Committee Co-Chairperson Committee Co-Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements Very special thanks to Rob Roberge, Mary Otis, Gina Frangello, Elizabeth Crane, Anthony McCann, Emily Rapp, Deanne Stillman, for teaching me everything I know about writing. To Michelle Camacho, Rebecca Gibbs, Gia Burton-Blasingame, Taylor Rubinstein, Jordan Rubinstein, Emily Rubinstein, Carol Gibbs, Greg Rush, Bill Gibbs, Linda Fox, Molly Rubinstein, Cheryl Fort, Sara Gibbs, Aaron Gibbs, Jaysin Graves, Hailey Gibbs, Persephone Gibbs, for giving me the time, space, motivation and encouragement, support and coffee needed to do this. To Stephanie Anne and Jason Metz for sharing your experience. To my chosen family, who loves me and supports me no matter what and to Tod Goldberg and Agam Patel for giving me a chance and for putting up with my craziness. iv This work is dedicated to my father, Bill Gibbs, who always encouraged me to use my imagination and follow my dreams.