2011 IIC STUDENT & EMERGING CONSERVATOR CONFERENCE CONSERVATION: FUTURES and RESPONSIBILITIES TRANSCRIPTS – 3 of 3 Session

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introducticn Tc Ccnservoticn

introducticntc ccnservoticn UNITED NATTONSEDUCATIONA],, SCIEIilIIFTC AND CULTIJRALOROANIZATTOII AN INIRODUCTION TO CONSERYATIOI{ OF CULTURAT PROPMTY by Berr:ar"d M. Feilden Director of the Internatlonal Centre for the Preservatlon and Restoratlon of Cultural Property, Rome Aprll, L979 (cc-ig/ws/ttt+) - CONTENTS Page Preface 2 Acknowledgements Introduction 3 Chapter* I Introductory Concepts 6 Chapter II Cultural Property - Agents of Deterioration and Loss . 11 Chapter III The Principles of Conservation 21 Chapter IV The Conservation of Movable Property - Museums and Conservation . 29 Chapter V The Conservation of Historic Buildings and Urban Conservation 36 Conclusions ............... kk Appendix 1 Component Materials of Cultural Property . kj Appendix 2 Access of Water 53 Appendix 3 Intergovernmental and Non-Governmental International Agencies for Conservation 55 Appendix k The Conservator/Restorer: A Definition of the Profession .................. 6? Glossary 71 Selected Bibliography , 71*. AUTHOR'S PREFACE Some may say that the attempt to Introduce the whole subject of Conservation of Cultural Propety Is too ambitious, but actually someone has to undertake this task and it fell to my lot as Director of the International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cxiltural Property (ICCROM). An introduction to conservation such as this has difficulties in striking the right balance between all the disciplines involved. The writer is an architect and, therefore, a generalist having contact with both the arts and sciences. In such a rapidly developing field as conservation no written statement can be regarded as definite. This booklet should only be taken as a basis for further discussions. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In writing anything with such a wide scope as this booklet, any author needs help and constructive comments. -

Conservation of Cultural and Scientific Objects

CHAPTER NINE 335 CONSERVATION OF CULTURAL AND SCIENTIFIC OBJECTS In creating the National Park Service in 1916, Congress directed it "to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life" in the parks.1 The Service therefore had to address immediately the preservation of objects placed under its care. This chapter traces how it responded to this charge during its first 66 years. Those years encompassed two developmental phases of conservation practice, one largely empirical and the other increasingly scientific. Because these tended to parallel in constraints and opportunities what other agencies found possible in object preservation, a preliminary review of the conservation field may clarify Service accomplishments. Material objects have inescapably finite existence. All of them deteriorate by the action of pervasive external and internal agents of destruction. Those we wish to keep intact for future generations therefore require special care. They must receive timely and. proper protective, preventive, and often restorative attention. Such chosen objects tend to become museum specimens to ensure them enhanced protection. Curators, who have traditionally studied and cared for museum collections, have provided the front line for their defense. In 1916 they had three principal sources of information and assistance on ways to preserve objects. From observation, instruction manuals, and formularies, they could borrow the practices that artists and craftsmen had developed through generations of trial and error. They might adopt industrial solutions, which often rested on applied research that sought only a reasonable durability. And they could turn to private restorers who specialized in remedying common ills of damaged antiques or works of art. -

4-10 Matting and Framing.Pdf

PRESERVATION LEAFLET CONSERVATION PROCEDURES 4.10 Matting and Framing for Works on Paper and Photographs NEDCC Staff NEDCC Andover, MA The importance of proper matting, mounting and framing Do not use any type of foam board such as Fom-cor®, is often overlooked as a key part of collections care and “archival” paper faced foam boards, Gator board, preventative conservation. Poor quality materials and expanded PVC boards such as Sintra® or Komatex®, any improper framing techniques are a common source of lignin containing paper-based mat boards, kraft (brown) damage to artwork and cultural heritage materials that paper, non-archival or self-adhesive tapes (i.e. document are in otherwise good condition. Staying informed about repair tapes), or ATG (adhesive transfer gum), all of which proper framing practices and choosing conservation-grade are used in the majority of frame shops. mounting, matting and framing can prevent many problems that in the future will be much more difficult to MATTING solve or even completely irreversible. As Benjamin Franklin said, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of The window mat is the standard mount for works on cure.” paper. The ideal window mat will be aesthetically pleasing while safely protecting the piece from exterior damage. Mats are an excellent storage method for works on paper CHOICE OF A FRAMER and can minimize the damage caused from handling in When choosing a framer it is important to find someone collections that are used for exhibition and study. Some well-informed about best conservation framing practices institutions simplify their framing and storage operations and experienced in implementing them. -

QAR Field Operations – May 2005

QAR Field Operations – October 2006 Artifact Conservation & Documentation Sarah Watkins-Kenney – QAR Project Chief Conservator Wendy Welsh—QAR Assistant Conservator I. Personnel: At least two members of the QAR Conservation & Documentation (C&D) team will be on site for each day of field operations. C&D Team: Sarah Watkins-Kenney (SWK) QAR Project Chief Conservator Wendy Welsh (WMW) QAR Assistant Conservator/(C&D Field Team Leader) Valerie Grussing (VJG) QAR Conservation Technician Franklin Price (FHP) Underwater Archaeology Technician Anne Corscadden-Knox (ACK) Underwater Archaeology Technician Steve Lambert (S L) Underwater Archaeology Technician Johnny Masters (JPM) Underwater Archaeology Technician Linda Carnes McNaughton (LCMN) Volunteer, Historian/Conservation assistant III. Documentation ON SITE includes: i TAGS- - Mylar or Tyvek are available from C&D team. - Must be tied to all artifact/concretions with cable ties so that tag lies on top surface as in situ. Provenance E & N taken to tag. - QAR# marked in industrial permanent black marker on both sides of the tag – while tag dry. For Fall 2006 – tags will be pre-numbered. - Additional information -marked in pencil (both types of tag can be written on with pencil underwater). - Information that must be on each tag, attached to artifacts, before they are brought to the surface: QAR#. - Additional information to be put on tag (either by field C&D or lab based C&D), Unit number in circle, E, N provenance, diver initials, date recovered. - For ballast, dredge/sieve material – one tag should be place inside bag and one tied to outside of container as appropriate. ii BAG & CONTAINER LABELS - - Each bag should be marked on outside, in permanent marker, with Unit #, E&N provenance, QAR#. -

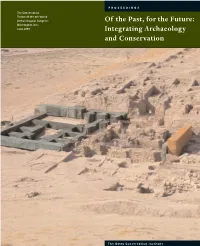

Integrating Archaeology and Conservation of Archaeology and Conservation the Past, Forintegrating the Future

SC 13357-2 11/30/05 2:39 PM Page 1 PROCEEDINGS PROCEEDINGS The Getty Conservation Institute The Conservation Los Angeles Theme of the 5th World Archaeological Congress Of the Past, for the Future: Washington, D.C. Printed in Canada June 2003 Integrating Archaeology and Conservation Of the Past, for the Future: Integrating Archaeology and Conservation The Getty Conservation Institute i-xii 1-4 13357 10/26/05 10:56 PM Page i Of the Past, for the Future: Integrating Archaeology and Conservation i-xii 1-4 13357 10/26/05 10:56 PM Page ii i-xii 1-4 13357 10/26/05 10:56 PM Page iii Of the Past, for the Future: Integrating Archaeology and Conservation Proceedings of the Conservation Theme at the 5th World Archaeological Congress, Washington, D.C., 22–26 June 2003 Edited by Neville Agnew and Janet Bridgland The Getty Conservation Institute Los Angeles i-xii 1-4 13357 10/26/05 10:56 PM Page iv The Getty Conservation Institute Timothy P. Whalen, Director Jeanne Marie Teutonico, Associate Director, Field Projects and Science The Getty Conservation Institute works internationally to advance conserva- tion and to enhance and encourage the preservation and understanding of the visual arts in all of their dimensions—objects, collections, architecture, and sites. The Institute serves the conservation community through scientific research; education and training; field projects; and the dissemination of the results of both its work and the work of others in the field. In all its endeavors, the Institute is committed to addressing unanswered questions and promoting the highest possible standards of conservation practice. -

Three Basic Book Repair Procedures - 1 | Back

Three Basic Book Repair Procedures - 1 | Back By Carole Dyal and Pete Merrill-Oldham Introduction Hinge Tightening I Hinge Tightening II Tipping-In Loose Pages Conclusions - References In libraries large and small, minor repair is a critical component in overall efforts to care for collections of books and journals. Bound volumes mended as soon as they show signs of damage may never require more complex repair or binding. A book with tightened hinges is sometimes more sturdy after treatment than it was at the time of purchase. Following are instructions for carrying out three basic cost-effective procedures for repairing hard-cover volumes. They were prepared to accompany all- day demonstrations presented at the 1998 Annual Meeting of the American Library Association in Washington, DC. The Library of Congress generously offered space in the LC exhibit booth in support of this pilot project. It focuses on early intervention as a means of delaying or eliminating the need for more time consuming and expensive treatment. This project was made possible through generous support from Acme Bookbinding (Charlestown, MA), Bridgeport National Bindery (Agawam, MA), Conservation Resources International (Springfield, VA), Gaylord Bros. (Syracuse, NY), Information Conservation Incorporated and the Etherington Conservation Center (Brown Summit, NC), the Library Binding Institute (Edina, MN), Library Binding Service (Des Moines, IA), Ocker & Trapp Library Bindery (Emerson, NJ), SOLINET (Atlanta, GA), and University Products (Holyoke, MA). Hinge Tightening I Inspect the hinge of the volume at the head and tail to see if the text block has become loose in its case. If the endpapers are pulling away from the inside of the case but are still securely attached to the text block, Hinge Tightening I may be an appropriate treatment. -

Conservation Technician Associate Conservator

POSITION DATA JOB TITLE: Conservation Technician DEPARTMENT: Collections REPORTS TO: Associate Conservator CLASSIFICATION: Nonexempt DATE: August 2021 POSITION OVERVIEW: The National September 11 Memorial & Museum seeks a Conservation Technician (CT) to serve as a ‘hands-on’ collections-care provider in the public spaces and storage areas of the Museum. The CT’s responsibilities will primarily support preventive conservation efforts at the Museum, working primarily with physical objects in the collection but supporting stewardship of the Museum’s accessioned digital assets. The CT will assist in the safe handling/transit, storage, exhibition and outgoing loan preparation, and routine maintenance of objects in the collection. The scope of these holdings is diverse in medium, scale, type, and inherent condition, and includes material evidence, memorial and tribute items, artwork, historical records, and web- based artifacts relating to the terrorist attacks of February 26, 1993, and September 11, 2001, and their repercussions. The incumbent reports to the Museum’s Associate Conservator. Work will generally take place during standard business hours. However, with advance notice, schedules may be adjusted to accommodate special projects which involve early morning or evening hours. Comprehensive training will be provided to familiarize the CT with the Museum’s equipment, software, art handling and PPE protocols and other collection policies. ESSENTIAL FUNCTIONS • Maintains and cleans open mount artifacts in the Museum’s exhibition spaces and monitors for any changes in condition. • Locates and moves objects to/from the Museum’s storage spaces and update locations in Collective Access, its collections management system. • Assists with preventive conservation activities including monitoring and collecting environmental data using data loggers and liaising with the Museum’s Integrated Pest Management vendor. -

Sarah M. Smith [email protected] Olfactorypress.Tumblr.Com

Sarah M. Smith [email protected] www.olfactorypress.com olfactorypress.tumblr.com Education 1998 & 2001 Rare Book School, Charlottesville, VA. Book Illustration to 1890, European Bookbinding, 1500-1800 and Books in the Manuscript Era 1994 The University of the Arts, Philadelphia, PA, MFA Book Arts/Printmaking 1990 The University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA, BA, Studio Art, minors in Art History and Latin Language and Literature 1988 The Academy of Fine Arts, Bruges, Belgium, Printmaking, Graphics and Art History Professional Experience 2013-Present Book Arts Special Instructor, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH Oversee Book Arts Workshop and manage all workshop activities including curricular support, instruction, planning, programming, supervision, equipment maintenance, ordering, recieving materials and budgeting. 2011 Instructor, Endicott College, Beverly, MA. Teaching courses in printmaking and letterpress printing to BFA students. 2010-2013 Visiting full-time faculty, Montserrat College of Art, Beverly, MA. Teaching full course load, serving on Faculty Affairs Committee in 2010 and Chair of Academic Planning Committee in 2011, as well as Book Arts Chair and manager of Imposition Press. 2008-2013 Book Arts Coordinator, Montserrat College of Art, Beverly, MA. Advising students on course selection and meeting requirements for Book Arts Major, managing curriculum, budget, faculty, equipment and supplies involved with the Book Arts Major. 2005-2013 Manager of Imposition Press, Montserrat College of Art, Beverly, MA. Working with college administrators creating business plan and goals for the college's letterpress and screenprint publishing endeavor. Procuring and scheduling projects; supervising interns and working with artists, authors and clients on projects. 2005-2013 Assistant Professor, Montserrat College of Art, Beverly, MA. -

Senior Conservation Technician Generic Job Description

Museum Job Function Senior Conservation Technician Grade 55 Summary Performs coordinating role for a museum activity, such as collection management or conservation. Performs a wide range of advanced conservation and administrative duties, requiring specialized knowledge of the collection. Oversees day to day workload and in absence of Conservator. Under general supervision, accomplishes most tasks independently, keeping supervisor informed of progress and problems. Typical Duties 1. Performs object preparation for exhibits, loans, and permanent storage, including customized housings for unconventional and/or fragile objects. 2. Performs conservation examinations, de-infestations, minor conservation treatments, and rehousing for museum objects. May implement preservation treatments. 3. Conducts wide variety of conservation functions, such as preparation of conservation condition reports (for planning purposes or objects in storage) and installations. 4. Maintains and documents storage areas and attends to routine storage/housing needs. 5. Assists with training conservators, students, and museum staff in object handling procedures. 6. Serves as an initial source of specialized information in a museum function, collection, or facility. 7. Advises visiting scholars, faculty, staff, students, colleagues, and general public in use or handling the collection. Facilitates use of collection by visitors and through loans and exchanges. 8. Responds to technical inquiries by phone and in person. May compose correspondence related to inquiries. 9. Performs research: searches local and national databases for information pertaining to materials and objects. 10. Develops and updates record keeping systems. Utilizes collections management database to create or maintain records. 11. Oversees workflow, schedules and trains other support staff, students, interns, casual employees, and volunteers. Assists with hiring process. -

Conservation Technician, Workshop Reference

Post: Conservation Technician, Workshop Reference: TG2109 Band: 5L Department: Conservation Contract: Fixed term contract until 31 March 2019 Hours: Full-time Reporting to: Senior Conservation Technician, Workshop Location: Tate Store, Southwark Background Tate aims to be the most artistically adventurous and culturally inclusive global art museum. We deliver this aim through activities in our four galleries across the UK (Tate Liverpool, Tate St Ives, Tate Britain and Tate Modern), our digital platforms and collaborations with our national and international partners. At the heart of Tate is our collection of art, which includes British art from the 16th century to the present day, and international modern art from 1900 to the present day. Tate is a British institution with an international outlook. Tate is recognised as one of the leading art organisations in the world, welcoming over 7 million visitors a year to its renowned programmes of exhibitions, displays and learning. Tate holds the national collection of British art from 1500 and the national collection of international modern and contemporary art from 1900, including works of art, library and archival material. At the heart of Tate is the collection, currently numbering over 70,000 works spanning five centuries and providing a magnificent resource for all four Tate galleries as well as for galleries and museums regionally, nationally and internationally. The collection is shared with as wide an audience as possible and is constantly being developed and added to, consolidating it historically and tracking contemporary art as it evolves. Collection Care Collection Care’s mission is to manage, preserve and enable access to Tate’s collections in both physical and digital format. -

Toward Common Nomenclature and Definitions for Natural Science Professional Collections-Related Positions" (2007)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Programs Information: Nebraska State Museum Museum, University of Nebraska State 2007 Toward Common Nomenclature and Definitions for Natural Science Professional Collections- Related Positions Paisley S. Cato University of Nebraska - Lincoln Hugh H. Genoways University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/museumprogram Part of the Anthropology Commons, Higher Education Commons, Life Sciences Commons, Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons, and the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Cato, Paisley S. and Genoways, Hugh H., "Toward Common Nomenclature and Definitions for Natural Science Professional Collections-Related Positions" (2007). Programs Information: Nebraska State Museum. 22. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/museumprogram/22 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Museum, University of Nebraska State at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Programs Information: Nebraska State Museum by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Cato & Genoways in Museum Studies: Perspectives and Innovations, Williams & Hawks, editors. Washington, DC: Society for the Preservation of Natural History Collections, 281 pp. Copyright 2007, SPNHC. Used by permission. TOWARD COMMON NOMENCLATURE AND DEFINITIONS FOR NATURAL SCIENCE PROFESSIONAL COLLECTIONS-RELATED POSITIONS Paisley S. Cato and Hugh H. Genoways (University ofNebraska, Lincoln) Abstract. - Analysis of recent literature ond experience with professional positions in several institutions provided the basis for praposing a basic grouping of titles for positions relating to the natural sciences collections profession. Six groups ore proposed with recommendations for educotion, experience, knowledge, and skills to support the key responsibilities ofthe positions. -

CITY of WALLA WALLA ARTS COMMISSION AGENDA Wednesday, August 5, 2020 – 11:00 AM Virtual Zoom Meting 15 N 3Rd Ave 1

City of Walla Walla Arts Commission Support Services 15 N. 3rd Avenue Walla Walla, WA 99362 CITY OF WALLA WALLA ARTS COMMISSION AGENDA Wednesday, August 5, 2020 – 11:00 AM Virtual Zoom Meting 15 N 3rd Ave 1. CALL TO ORDER 2. APPROVAL OF MINUTES a. March 4, 2020 and July 8, 2020 3. ACTIVE BUSINESS a. Deaccession of Public Art – Policy Discussion b. City Flag Project • Update on Status of this Project – Brenden Koch 4. STAFF UPDATE 5. COMMUNITY COMMENTS 6. ADJOURNMENT To join Zoom Meeting: https://us02web.zoom.us/j/89210971084 Meeting ID: 892 1097 1084 One tap mobile – 1(253) 215-8782 Persons who need auxiliary aids for effective communication are encouraged to make their needs and preferences known to the City of Walla Walla Support Services Department three business days prior to the meeting date so arrangements can be made. The City of Walla Arts Commission is a seven-member advisory body that provides recommendations to the Walla Walla City Council on matters related to arts within the community. Arts Commissioners are appointed by City Council. Actions taken by the Arts Commission are not final decisions; they are in the form of recommendations to the City Council who must ultimately make the final decision. MEMORANDOM TO: Arts Commission FROM: Elizabeth Chamberlain, AICP, Deputy City Manager DATE: July 29, 2020 RE: Policy Development – Deaccessioning Public Art The Arts Commission began a discussion on deaccessioning public art earlier this year. With the recent protests on racial iniquity as well as public art representing figures in history associated with racial iniquity, the City of Walla Walla should consider developing a policy on public art deaccessioning, disposition, and transfer.