After Brexit, Will Ireland Be Next to Exit?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE CYPRUS QUESTION in the MAKING and the ATTITUDE of the SOVIET UNION TOWARDS the CYPRUS QUESTION (1960-1974) a Master's

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bilkent University Institutional Repository THE CYPRUS QUESTION IN THE MAKING AND THE ATTITUDE OF THE SOVIET UNION TOWARDS THE CYPRUS QUESTION (1960-1974) A Master’s Thesis by MUSTAFA ÇAĞATAY ASLAN DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS BILKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA September 2008 To my grandfathers Osman OYMAK and Mehmet Akif ASLAN, THE CYPRUS QUESTION IN THE MAKING AND THE ATTITUDE OF THE SOVIET UNION TOWARDS THE CYPRUS QUESTION (1960-1974) The Institute of Economics and Social Sciences of Bilkent University by MUSTAFA ÇAĞATAY ASLAN In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in THE DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS BILKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA September 2008 I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations. --------------------------- Associate Prof. Hakan Kırımlı Supervisor I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations. --------------------------- Assistant Prof. Dr. Nur Bilge Criss Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations. --------------------------- Assistant Prof. Dr. Eugenia Kermeli Examining Committee Member Approval of the Institute of Economics and Social Sciences --------------------------- Prof. Dr. Erdal Erel Director ABSTRACT THE CYPRUS QUESTION IN THE MAKING AND THE ATTITUDE OF THE SOVIET UNION TOWARDS THE CYPRUS QUESTION (1960-1974) Aslan, Mustafa Çağatay M.A., Department of International Relations Supervisor: Associate Prof. -

Brexit and Jersey

BREXIT AND JERSEY Mark Boleat April 2016 Executive summary On June 23rd voters in the United Kingdom will decide whether the UK should remain a member of the European Union. The decision will be of massive importance to the UK, a “leave” vote being followed by years of uncertainty as Britain seeks to establish a new economic relationship not just with the European Union but also with the rest of the world. By extension, the vote will also be of crucial importance to Jersey, given that Jersey’s economy is closely tied to that of the UK and Jersey’s prosperity depends on it being semi- detached to the UK. When Britain decided to seek to join the then EEC in 1971 this was seen as potentially very damaging to Jersey, at the least resulting in increased competition for agricultural products, and at worst threatening the tourism and finance industries if Jersey were to be subject to the full rules of the EEC. In the event Jersey got the best possible deal - inside the common external tariff but outside the EEC generally. These arrangements were set out in Protocol 3 to the 1972 Accession Treaty. In practice, Jersey became loosely attached to the EEC as well as semi-detached to the UK. This was achieved through low- key way, but with good preparation in both Jersey and the UK. The Brexit debate in the UK is as much emotional as rational. Business is strongly in favour of Britain remaining in the EU but finds it difficult to engage in such a debate. -

Anglo-Saxon and Scots Invaders

Anglo-Saxon and Scots Invaders By around 410AD, the last of the Romans had left Britain to go back to Rome and England was left to look after itself for the first time in about 400 years. Emperor Honorius told the people to fight the Picts, Scots and Saxons who were attacking them, but the Brits were not good fighters. The Scots, who came from Ireland, invaded and took land in Scotland. The Scots split Scotland into 4 separate places that were named Dal Riata, Pictland, Strathclyde and Bernicia. The Picts (the people already living in Scotland) and the Scots were always trying to get into England. It was hard for the people in England to fight them off without help from the Romans. The Picts and Scots are said to have jumped over Hadrian’s Wall, killing everyone in their way. The British king found it hard to get his men to stop the Picts and Scots. He was worried they would take over in England because they were excellent fighters. Then he had an idea how he could keep the Picts and Scots out. He asked two brothers called Hengest and Horsa from Jutland to come and fight for him and keep England safe from the Picts and Scots. Hengest and Horsa did help to keep the Picts and Scots out, but they liked England and they wanted to stay. They knew that the people in England were not strong fighters so they would be easy to beat. Hengest and Horsa brought more men to fight for England and over time they won. -

RTÉ Annual Report 2014

Annual Report & Group Financial Statements 2014 Raidió Teilifís Éireann Board 54th Annual Report and Group Financial Statements for the twelve months ended 31 December 2014, presented to the Minister for Communications, Energy and Natural Resources pursuant to section 109 and 110 of the Broadcasting Act 2009. Is féidir leagan Gaeilge den Tuarascáil a íoslódáil ó www.rte.ie/about/ie/policies-and-reports/annual-reports/ 2 CONTENTS Vision, Mission and Values 2 A Highlights 3 Chair’s Statement 4 Director-General’s Review 6 Financial Review 10 What We Do 16 Organisation Structure 17 Operational Review 18 Board 84 B Executive 88 Corporate Governance 90 Board Members’ Report 95 Statement of Board Members’ Responsibilities 96 Independent Auditor’s Report 97 Financial Statements 98 C Accounting Policies 105 Notes Forming Part of the Group Financial Statements 110 Other Reporting Requirements 149 Other Statistical Information 158 Financial History 159 RTÉ ANNUAL REPORT & GROUP FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 2014 1 RTÉ’S DirecTOR-GENERAL has SET RTÉ’S VISION, MISSION AND VALUes STATEMENT Vision RTÉ’s vision is to enrich Irish life; to inform, entertain and challenge; to connect with the lives of all the people. Mission • Deliver the most trusted, independent, Irish news service, accurate and impartial, for the connected age • Provide the broadest range of value for money, quality content and services for all ages, interests and communities • Reflect Ireland’s cultural and regional diversity and enable access to major events • Support and nurture Irish production and Irish creative talent Values • Understand our audiences and put them at the heart of everything we do • Be creative, innovative and resourceful • Be open, collaborative and flexible • Be responsible, respectful, honest and accountable to one another and to our audiences 2 HIGHLIGHTS A RTÉ ANNUAL REPORT & GROUP FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 2014 3 CHAIR’S STATEMENT The last year has been one of transition for RTÉ and for its Board. -

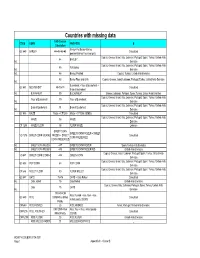

Countries with Missing Data

Countries with missing data FAO Code or CODE GEMS FAO FOOD B Calculation Barley+Pot Barley+Barley, GC 640 BARLEY 44+45+46+48 Calculated pearled+Barley Flour and grits Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab 44 BARLEY Int. Emirates Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab 45 Pot Barley Int. Emirates Int. 46 Barley, Pearled Cyprus; Turkey; United Arab Emirates 48 Barley Flour and Grits Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Lebanon; Portugal; Turkey; United Arab Emirates Int. Buckwheat + flour of buckwheat + GC 641 BUCKWHEAT 89+90+91 Calculated Bran of buckwheat Int. BUCKWHEAT 89 BUCKWHEAT Greece; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab Emirates Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab Flour of Buckwheat 90 Flour of Buckwheat Int. Emirates Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab Bran of Buckwheat 91 Bran of Buckwheat Int. Emirates GC 645 MAIZE Maize + CF1255 Maize + CF1255 (GEMS) Calculated Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab MAIZE 56 MAIZE Emirates CF 1255 MAIZE FLOUR 58 FLOUR MAIZE Lebanon SWEET CORN SWEET CORN FROZEN + SWEET VO 1275 SWEET CORN (KERNEL FROZEN + SWEET Calculated CORN PRESERVED CORN PRESERVED Int. SWEET CORN FROZEN 447 SWEET CORN FROZEN Spain; United Arab Emirates Int. SWEET CORN PRESERV 448 SWEET CORN PRESERVED United Arab Emirates Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab VO 447 SWEET CORN (CORN-O 446 GREEN CORN Emirates Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab GC 656 POP CORN 68 POP CORN Emirates Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab CF 646 MILLET FLOUR 80 FLOUR MILLET Emirates GC 647 OATS 75+76 OATS + Oats Rolled Calculated Int. -

2017 Fall Edition

Oasis of Glenmont Cyprus Shriners Desert of New York FALL 2017 HAVING FUN. HELPING KIDS INSIDE THIS ISSUE POTENTATE’S MESSAGE 3 FALL CEREMONIAL 6 MEMBERSHIP 9 MILLION DOLLAR CLUB 13 CHIEF RABBAN’S MESSAGE 4 POTENTATE’S BALL 7 CHRISTMAS PARTY 10 UPCOMING EVENTS 14 www.cyprusshriners.com PAGE 2 CYPRUS NEWS Cyprus News Vote on proposed change to the By-Laws at Published Quarterly by Cyprus Shriners 9 Frontage Road, Glenmont, NY 12077 stated meeting Wednesday September 20, 2017 Tel: (518) 436-7892 Email: [email protected] ARTICLE V Website: www.cyprus5.org Initiation Fees, Dues, Per Capita, Hospital Levy Section 5.1 Initiation Fee The initiation fee shall 2017 Elected Divan be determined at a stated or special meeting of the Potentate Ill. Anthony T. Prizzia, Sr. (845) 691-2021 temple after notice has been given to each member [email protected] stating the proposed amount of the initiation fee. It Chief Rabban David M. Unser (518) 207-6711 must be paid in full prior to initiation. [email protected] Assistant Rabban Robert Baker (518) 857-8187 At this time the Fee for Initiation is $100.00, but [email protected] High Priest & Prophet John Donato (518) 479-0315 does not appear in the By Laws. [email protected] Oriental Guide Chris Wessell (518) 269-2262 We ask that the Initiation Fee be raised to $150.00. [email protected] Treasurer James H. Pulver (518) 326-1196 The reason for the increase is to provide every new [email protected] Noble with a Felt Embroidered Cyprus Fez at his Recorder Ill. -

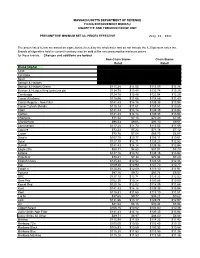

Cigarette Minimum Retail Price List

MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE FILING ENFORCEMENT BUREAU CIGARETTE AND TOBACCO EXCISE UNIT PRESUMPTIVE MINIMUM RETAIL PRICES EFFECTIVE July 26, 2021 The prices listed below are based on cigarettes delivered by the wholesaler and do not include the 6.25 percent sales tax. Brands of cigarettes held in current inventory may be sold at the new presumptive minimum prices for those brands. Changes and additions are bolded. Non-Chain Stores Chain Stores Retail Retail Brand (Alpha) Carton Pack Carton Pack 1839 $86.64 $8.66 $85.38 $8.54 1st Class $71.49 $7.15 $70.44 $7.04 Basic $122.21 $12.22 $120.41 $12.04 Benson & Hedges $136.55 $13.66 $134.54 $13.45 Benson & Hedges Green $115.28 $11.53 $113.59 $11.36 Benson & Hedges King (princess pk) $134.75 $13.48 $132.78 $13.28 Cambridge $124.78 $12.48 $122.94 $12.29 Camel All others $116.56 $11.66 $114.85 $11.49 Camel Regular - Non Filter $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Camel Turkish Blends $110.14 $11.01 $108.51 $10.85 Capri $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Carlton $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Checkers $71.54 $7.15 $70.49 $7.05 Chesterfield $96.53 $9.65 $95.10 $9.51 Commander $117.28 $11.73 $115.55 $11.56 Couture $72.23 $7.22 $71.16 $7.12 Crown $70.76 $7.08 $69.73 $6.97 Dave's $107.70 $10.77 $106.11 $10.61 Doral $127.10 $12.71 $125.23 $12.52 Dunhill $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Eagle 20's $88.31 $8.83 $87.01 $8.70 Eclipse $137.16 $13.72 $135.15 $13.52 Edgefield $73.41 $7.34 $72.34 $7.23 English Ovals $125.44 $12.54 $123.59 $12.36 Eve $109.30 $10.93 $107.70 $10.77 Export A $120.88 $12.09 $119.10 $11.91 -

Review Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-Cov)

Review Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): A review Nour Ramadan1, Houssam Shaib2,* Abstract As a novel coronavirus first reported by Saudi Arabia in 2012, the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) is responsible for an acute human respiratory syndrome. The virus, of 2C beta- CoV lineage, expresses the dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) receptor and is densely endemic in dromedary camels of East Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. MERS-CoV is zoonotic but human-to-human transmission is also possible. Surveillance and phylogenetic researches indicate MERS-CoV to be closely associated with bats’ coronaviruses, suggesting bats as reservoirs, although unconfirmed. With no vaccine currently available for MERS-CoV nor approved prophylactics, its global spread to over 25 countries with high fatalities highlights its role as ongoing public health threat. An articulated action plan ought to be taken, preferably from a One Health perspective, for appropriately advanced countermeasures against MERS-CoV. Keywords MERS-CoV, Lebanon, epidemiology, One Health. 3 Introduction1 with pneumonia and acute kidney injury. The June 19th, 2017, a case of Middle East virus was later isolated from the patient’s sputum. respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) is A different report appeared in September 2012, reported by the National International Health detecting a similar virus with 99.5% identity in a Regulation (IHR) focal point of Lebanon.1 As a previous patient who initially developed novel coronavirus, MERS-CoV was first symptoms in Qatar and had traveled to Saudi identified in a patient from the Kingdom of Arabia before the disease progression Saudi Arabia in June 2012 and was originally exacerbated.4 Seroepidemiologic and virologic named human coronavirus-EMC, as in Erasmus research revealed MERS-CoV infection in Medical Center.2 The case involved a man in dromedary camels (Camelus dromedarius) with Saudi Arabia who was admitted to the hospital isolated viruses from dromedaries competent in 5,6 infecting the human respiratory tract. -

The Influence of British and American Cultural Differences on English and American Literature Review Jiao

2016 4th International Conference on Advances in Social Science, Humanities, and Management (ASSHM 2016) ISBN: 978-1-60595-412-7 The Influence of British and American Cultural Differences on English and American Literature Review Jiao Lei1 Abstract In an era of globalization, cross-cultural communication is not strange to us with studying and travelling abroad, and even immigration becoming a part of our lives. In such an era of international communication being increasingly frequent, learning the culture of other countries will help us to do well in international communication. The paper is going to study, from the British and American history and culture, the differences of all kinds of their present acts in the world and impacts of the historical reasons on their own citizens, to not only let the reader understand the cultural differences between these two countries, but also to get the cause of the difference to better understand their cultures. Key words: British and American Culture; Religion; Literature Review 1 INTRODUCTION First of all, we are going to talk about the homology of British and American culture which is undeniable. British culture is the root and source of American culture with the United Kingdom people accounting for a very large proportion of the early settlers of the United States. Let nature take its course, they brought their culture, their personalities, ways of thinking to this new continent. Moreover, in the major historical events of modern times, many cooperation has occurred in these two countries which brought many common points in their cultural exchanges. However, there is a large difference between these two countries regarding to their own history: the history of Britain is longer than the United States’, because before the industrial revolution, Britain has a long period of agriculture civilization, and much British people's cultural life has been influenced by the upper class of French due to the French occupation. -

Annual Conference

Mr John Webster Mr Michael D’Arcy Mr John Webster is the Scottish Government Mr Michael D’Arcy was the joint editor of the Representative to Ireland. He heads a team of four seminal publication on the all-island economy ANNUAL CONFERENCE officials at the Scottish Government Office, located Border Crossings : Developing Ireland’s Island in the British Embassy in Dublin. John has been a Economy (Gill&Macmillan 1995). Since then he has Crowne Plaza Hotel, Dundalk career diplomat for 29 years. Before his current role, been involved in many all-island economic and he was Political Counsellor in the British Embassy business policy initiatives including research work 8 & 9 March 2018 to Ireland from April 2012 until January 2016. Prior for the Centre for Cross Border Studies; the ESRI; to Ireland, John was a political adviser for NATO in the European Economic and Social Committee; Helmand Province in 2010/11, before which he was Head of Humanitarian Inter Trade Ireland; Co-operation Ireland and Ulster University. #CCBSconf Policy in the UK Department for International Development, where he participated in humanitarian missions, including to the DRC and Chad. John His most recent published report is Delivering a Prosperity Process: served on postings in the UK’s Mission to the UN in Geneva, the UK Opportunities in North/South Public Service Provision completed for the Delegation to the Council of Europe in Strasbourg, and in Embassies in Cyprus, Centre for Cross Border Studies in 2012 and supported by the Department Romania, New Zealand and Mauritius, with spells in London between postings. -

Britishness: Towards a Progressive Citizenship

Britishness_Text.qxd 13/3/07 15:21 Page 1 THE SMITH INSTITUTE Britishness: towards a progressive citizenship Edited by Nick Johnson Published by the Smith Institute ISBN 1 905370 18 0 This report, like all Smith Institute monographs, represents the views of the authors and not those of the Smith Institute. © The Smith Institute 2007 Britishness_Text.qxd 13/3/07 15:21 Page 2 THE SMITH INSTITUTE Contents Preface By Wilf Stevenson, Director, Smith Institute 3 Introduction Nick Johnson, Director of Policy and Public Sector at the Commission 4 for Racial Equality Chapter 1: The progressive value of civic patriotism 14 Professor Todd Gitlin, Sociologist and Author Chapter 2: Is Britishness relevant? 22 Sadiq Khan, Labour MP for Tooting Chapter 3: Immigration and national identity 30 Robert Winder, Author Chapter 4: Britishness and integration 38 Trevor Phillips, Chair of the Commission for Equality & Human Rights and formerly Chair of the Commission for Racial Equality Chapter 5: Not less immigration, but more integration 48 Nick Pearce, Director of the Institute for Public Policy Research Chapter 6: Belonging – local and national 60 Geoff Mulgan, Director of the Young Foundation, and Rushanara Ali, Associate Director of the Young Foundation Chapter 7: Devolution – the layers of identity 68 Catherine Stihler, Labour MEP for Scotland Chapter 8: Citizenship education and identity formation 76 Tony Breslin, Chief Executive of the Citizenship Foundation Chapter 9: Faith and nation 84 Madeleine Bunting, Journalist and Author Endnote: Towards a progressive British citizenship? 94 Nick Johnson 2 Britishness_Text.qxd 13/3/07 15:21 Page 3 THE SMITH INSTITUTE Preface Wilf Stevenson, Director, Smith Institute The Smith Institute is an independent think tank which has been set up to undertake research and education in issues that flow from the changing relationship between social values and economic imperatives. -

Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Transmission Marie E

PERSPECTIVE Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Transmission Marie E. Killerby, Holly M. Biggs, Claire M. Midgley, Susan I. Gerber, John T. Watson (Figure). MERS-CoV human cases result from primary Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS- or secondary transmission. Primary transmission is CoV) infection causes a spectrum of respiratory illness, classified as transmission not resulting from contact from asymptomatic to mild to fatal. MERS-CoV is transmitted sporadically from dromedary camels to humans with a confirmed human MERS case-patient 15( ) and can and occasionally through human-to-human contact. result from zoonotic transmission from camels or from Current epidemiologic evidence supports a major role in an unidentified source. Conzade et al. reported that, transmission for direct contact with live camels or humans among cases classified as primary by the WHO, only 191 with symptomatic MERS, but little evidence suggests (54.9%) persons reported contact with dromedaries (15). the possibility of transmission from camel products or Secondary transmission is classified as transmission asymptomatic MERS cases. Because a proportion of case- resulting from contact with a human MERS case- patients do not report direct contact with camels or with patient, typically characterized as healthcare-associated persons who have symptomatic MERS, further research is or household-associated, as appropriate. However, needed to conclusively determine additional mechanisms many MERS case-patients have no reported exposure to of transmission, to inform public health practice, and to a prior MERS patient or healthcare setting or to camels, refine current precautionary recommendations. meaning the source of infection is unknown. Among 1,125 laboratory-confirmed MERS-CoV cases reported iddle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coro- to WHO during January 1, 2015–April 13, 2018, a total Mnavirus (MERS-CoV) was first detected in Sau- of 157 (14%) had unknown exposure (15).