An Alternative Report to the Fifth State Party Periodic Report to UNCRC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See Resource File

Prospects and Opportunities of International Cooperation in Attaining SDG Targets in Bangladesh (Global Partnership in Attainment of the SDGs) General Economics Division (GED) Bangladesh Planning Commission Ministry of Planning Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh September 2019 Prospects and Opportunities of International Cooperation in Attaining SDG Targets in Bangladesh Published by: General Economics Division (GED) Bangladesh Planning Commission Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Sher-e-Bangla Nagar, Dhaka-1207, Bangladesh Website: www.plancomm.gov.bd First Published: September 2019 Editor: Dr. Shamsul Alam, Member (Senior Secretary), GED Printed By: Inteshar Printers 217/A, Fokirapool, Motijheel, Dhaka. Cell: +88 01921-440444 Copies Printed: 1000 ii Bangladesh Planning Commission Message I would like to congratulate General Economics Division (GED) of the Bangladesh Planning Commission for conducting an insightful study on “Prospect and Opportunities of International Cooperation in Attaining SDG Targets in Bangladesh” – an analytical study in the field international cooperation for attaining SDGs in Bangladesh. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) agenda is an ambitious development agenda, which can’t be achieved in isolation. It aims to end poverty, hunger and inequality; act on climate change and the environment; care for people and the planet; and build strong institutions and partnerships. The underlying core slogan is ‘No One Is Left Behind!’ So, attaining the SDGs would be a challenging task, particularly mobilizing adequate resources for their implementation in a timely manner. Apart from the common challenges such as inadequate data, inadequate tax collection, inadequate FDI, insufficient private investment, there are other unique and emerging challenges that stem from the challenges of graduation from LDC by 2024 which would limit preferential benefits that Bangladesh have been enjoying so far. -

The Power of Using the Right to Information Act in Bangladesh

World Bank Group The Power of Using the Right to Information Act in Bangladesh: Experiences from the Ground World Bank Institute 1 Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………... Pg. 3 Story #1: Rezia Khatun used the RTI Act to get a Vulnerable Group Development (VGD) card…………………………………………………………………………………………... Pg. 5 Story #2: Shamima Akter uses the RTI Act to help vulnerable women to access government programs in her village………………………………………………………………………… Pg. 6 Story #3: Jobeda Begum uses information to increase the beneficiaries on a government program………………………………………………………………………………………. Pg. 7 Story #4: Rafiqul Islam demands information to bring transparency to the distribution of grains. Pg. 8 Story #5: RTI Act helps in implementing minimum wage in shrimp processing………………... Pg. 9 Story #6: The use of RTI for environmental advocacy against illegal building………………….. Pg. 11 Story #7: Mosharaf Hossain uses the RTI Act to ensure that his online complaint for migrant workers is heard……………………………………………………………………………… Pg. 13 Story #8: Information Commission helps Mosharef Hossain Majhi to access information on agriculture issues…………………………………………………….……………. Pg. 15 Story #9: By using the RTI Act, poor women receive access to maternal health vouchers…….. Pg. 17 Story #10: Landless committees use the RTI Act to gain access to land records……………… Pg. 19 Story #11: RTI Act helps improve the lives of fishermen……………………………………... Pg. 21 Story #12: By using the RTI Act, Mohammad gets access to the Agriculture Input Assistance Card…………………………………………………………………………………………. Pg. 23 Story #13: RTI helps to place names on a list of beneficiaries in government program………. Pg. 25 Story #14: Rabidas community utilizes RTI for getting Old Age Pension in Saidpur, Nilphamari. Pg. 26 Story #15: RTI Act enables Munna Das to get information from the youth development officer. -

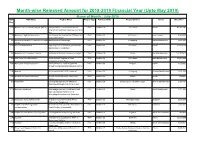

Upto May 2019) Name of Month : July-2018 NGO NGO Name Project Name Project Type Released Date Project District Sector Allocation Reg

Month-wise Released Amount for 2018-2019 Financial Year (Upto May 2019) Name of Month : July-2018 NGO NGO Name Project Name Project Type Released Date Project District Sector Allocation Reg. 2473 Medicins Sans Frontieres-Belgium (MSFB) Ukhiya the Host Community Outreach FD-6 2018-Jul-26 Cox's Bazar Health 83,062,387 Program and Outbreak Response Coxs bazar Dist 55 Madaripur Legal Aid Association Lets Cleanup the Country Day 2018 and Lets FD-6 2018-Jul-25 All Districts, Environment 6,000,000 Build Green Schools 135 Mohamuni Bidhaba-O-Anath Shishu Kalyan Maintenance of Orphanage FD-6 2018-Jul-22 Chittagong, Social Development 3,032,500 Kendra 2266 Nutrition International Operating Cost of Alleviating Micronutient FD-6 2018-Jul-01 All Districts, Health 45,604,296 Malnutrition in Bangladesh 665 Medecins Sans Frontieres - France Re-Launch of Mission Coordination Project FD-6 2018-Jul-28 Dhaka, Social Development 123,787,691 476 NGO Forum For Public Health WASH Support Program for Host FD-6 2018-Jul-28 Cox's Bazar Local Government 37,867,093 Community in Coxs Bazar 2997 Mafizuddin Nazeda Foundation Rural Community Health Programme FD-6 2018-Jul-09 Dinajpur, Health 1,100,000 through Mofizuddin Mazed Medical Centre 1181 Mamata HER Project-MAMATA(HER Finance) FD-6 2018-Jul-09 Chittagong, Women Development 5,691,289 1982 Mosabbir Memorial foundation Strenthening of Mosabbir Cancer Care FD-6 2018-Jul-09 Dhaka, Health 834,827 Centre 943 Naripokkho Claiming the Right to Safe Menstrual FD-6 2018-Jul-29 Dhaka, Barisal, Patuakhali, Bogra, Women Development -

The Millennium Development Goals

The Millennium Development Goals Bangladesh Progress Report 2009 General Economics Division Planning Commission Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh The Millennium Development Goals Bangladesh Progress Report 2009 General Economics Division Planning Commission Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh The Millennium Development Goals Progress Report 2009 has been benefited from the financial and technical assistance of the United Nations System in Bangladesh. The Millennium Development Goals The Millennium Development Goals Bangladesh Progress Report 2009 Design & Published by General Economics Division Planning Commission Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Bangladesh Progress Report 2009 Copies printed: 2500 Printed by Scheme Service Genesis (Pvt.) Ltd., Dhaka, Bangladesh The Millennium Development Goals Bangladesh Progress Report 2009 Message Air Vice Marshal (Retd.) A. K. Khandker The Millennium Development Goals Minister Ministry of Planning Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh I am happy to learn that the General Economics Division (GED) of the Bangladesh Planning Commission has prepared the `Millennium Development Goals: Bangladesh Progress Report 2009’ taking inputs from relevant ministries and related stakeholders along with the technical assistance from the UN Systems. As the coming Sixty-fifth session of the United Nations General Assembly, inter alia, will review the latest achievements of the MDGs, the report will be supportive to do the same for Bangladesh The Government of Bangladesh is committed to achieve the MDGs within the given timeframe and accordingly prepared an action plan. The National Strategy for Accelerated Poverty Reduction (NSAPR-1), the Medium Term Budgetary Framework (MTBF) and the Annual Development Programs (ADPs) have also been tuned towards achieving the MDGs. -

Country Youth Prof Ile - Bangladesh

Country Youth Prof ile - Bangladesh Country Youth Prof ile BANGLADESH Women and Youth Empowerment Division Resilience and Social Development Department February 201 1 1. Socio-economic Profile 1.1. The People’s Republic of Bangladesh is located on the North-eastern part of South Asia, with a projected pop- ulation of 167,414.566 in 20191. The country experienced a steady economic growth rate between 2010-2017 with its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) averaging over 6% annually reaching a peak of 7.3% in 2017, the highest in the country’s history2. Bangladesh has made remarkable progress in reducing poverty. The population living below the national poverty line dropped from 31.5% in 2010 to 24.3% in 20163. The proportion of the employed living below the $1.90 purchasing power parity (PPP) a day dropped from 44.2% in 1991 to14.8% in 2016/20174. In parallel, the country achieved a lower middle-income status in 2015 and qualified for graduation from a Least Developing Coun- try in March 2018 and is on track for graduation in 20245. 1.2 Bangladesh’s position on the United Nations Development Program’s (UNDP) 2017 Human Development Index (HDI) moved up three positions from its 2016 rank of 139th to 136th out of 189 countries6. However, Bangladesh’s HDI of 0.608 is below the average of 0.631 and 0.645 for the medium human development category and South Asian countries respectively7. 1.3. The official characterization of youth in Bangladesh refers to persons between ages 18-35. However, the youth data from the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) is based on the 15-29-years age range. -

Sustainability Report 2014

SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2014 Concept & Design by Forethought PR Limited I www.forethoughtpr.com This is Grameenphone Grameenphone, part of the Telenor Group, is the leading telecommunications service provider in Bangladesh. Since its inception in 1997, Grameenphone has built the largest cellular network in the country, covering nearly 99 percent of the country's population. With its brand promise, to enable customers to “Go beyond”, Grameenphone seeks to help customers get the full benefit of mobile data and voice services and provide Internet For All. Before Grameenphone’s inception, the phone was for a selected urbanized few. The cell phone was a luxury: a flouting accessory for the select elite. The mass could not contemplate mobile telephony as being part of their lives. Due to its long term commitment to Bangladesh, the company swiftly expanded its network around the country, providing affordable communication solutions to all. Grameenphone is listed on the Dhaka Stock Exchange. It is also among the top contributors to the government exchequer. The company has also created employment for a large number of people both directly and indirectly. The telecom industry has the power to transform society. Our influence represents a I am pleased to present the Grameenphone Sustainability Report for 2014. This Report great opportunity but also a significant responsibility. That’s why sustainability is at the provides an overview of Grameenphone’s actions and results in terms of social and core of Telenor Group’s approach to doing business in all its markets. I’m pleased to see environmental performance. that Grameenphone is now publishing its sustainability report. -

Institutionalizing Local Level Poverty Monitoring System (LLPMS)

Institutionalizing Local Level Poverty Monitoring System (LLPMS) Bangladesh Academy for Rural Development (BARD) Kotbari, Comilla Bangladesh July 2013 0 | P a g e I Project Overview 1 Title of the Institutionalizing Local Level Poverty Monitoring System (LLPMS) Project 2 Project Proponent a Name of Bangladesh Academy for Rural Development (BARD) Institution b Name of Head of Mr. Md. Mashiur Rahman Institution c Mailing Address Kotbari, Comilla, Bangladesh d Telephone and Tel. +88 081 60600 Fax Numbers Fax. +88 081 68406 e E-mail Address [email protected] f Web-site www.bard.gov.bd g Brief Profile of Bangladesh Academy for Rural Development (BARD) was established the Proponent in 1959 basically as a training institute. In course of time, however, it Institution has combined training with research and pilot experimentation. The unified approach of training, research and pilot experimentation to solve problems of rural areas has given special significance to the activities of the Academy. Bangladesh Academy for Rural Development (BARD) as a national institute of rural development in Bangladesh is mandated to perform specific functions which are: 1) provide training to government officials and others concerned with rural development; 2) conduct research in rural development and allied fields; 3) test and experiment on concepts and theories of development; 4) provide advisory and consultative service to the Government and other agencies; 5) guide and supervise students, national and foreign, in their dissertation works; 6) arrange and conduct national and international seminars, conferences and workshops, and 7) help policy planners in the field of rural development. In order to perform these functions, it has 09 divisions, of which four are service divisions and 05 are academic divisions. -

Combatting Black Money, Corruption and Money Laundering in Bangladesh: the Ogd Must Bark to Keep Predators Away' S M

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts 2018 'Captured by Evils' - Combatting Black Money, Corruption and Money Laundering in Bangladesh: The ogD Must Bark to Keep Predators Away' S M. Solaiman University of Wollongong, [email protected] Publication Details S. M. Solaiman, ''Captured by Evils' - Combatting Black Money, Corruption and Money Laundering in Bangladesh: The oD g Must Bark to Keep Predators Away'' (2018) 21 (3) Journal of Money Laundering Control 264-289. Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] 'Captured by Evils' - Combatting Black Money, Corruption and Money Laundering in Bangladesh: The ogD Must Bark to Keep Predators Away' Abstract Purpose: The purpose of this paper is to demonstrate that the recurrent amnesties to black money holders (BMHs) in Bangladesh have not benefited the national economy, rather have increased corruption and money laundering, and that offering further opportunity to whiten back money as recommended by the Anti- Corruption Commission of Bangladesh will do more harm than good. Design/methodology/approach: This research relies on both primary and secondary materials adopting an archival analysis of the existing literature. Findings: The am jor findings include the following: the recurrent amnesties to BMHs have damaging impacts on corruption and money laundering in Bangladesh; the Anti-Corruption Commission of Bangladesh's recommendation to provide further opportunity to legalise black money is flawed, ill thought-out and misjudgement of the futility of the amnesties offered to date; and the black money problem could be better addressed through using educational, preventive and punitive measures that have been specifically formulated in this paper. -

Working Paper: Government Policies and Practices on YOUTH

Working Paper Government Policies and Practices on YOUTH October 3, 2018 Table of Contents A. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................ 2 B. Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 3 C. Policy Prospect ................................................................................................................... 4 D. Description .......................................................................................................................... 5 National Education Policy (NEP), 2010 .................................................................................................... 7 Higher Education Quality Enhancement Project (HEQEP), 2010 ............................................................ 9 Sheikh Hasina National Youth Development Institute Act, 2017 ............................................................ 10 National Youth Policy, 2017 .................................................................................................................... 10 National Skills Development Policy (NSDP), 2011 ................................................................................. 11 National Telecommunications Policy (NTP), 2013 ................................................................................. 12 Seventh Five Years Plan (7th FYP), 2016-2020 ..................................................................................... -

English for Today- Class-11-12

Prescribed by the National Curriculum and Textbook Board as a textbook for classes XI-XII & Alim ENGLISH FOR TODAY Classes XI-XII & Alim Writers Quazi Mustain Billah Fakrul Alam M Shahidullah Shamsad Mortuza Zulfeqar Haider Goutam Roy Editors Syed Manzoorul Islam Shaheen M. Kabir ft._,.1) NATIONAL CURRICULUM AND TEXTBOOK BOARD,BANGLADESH Published by National Curriculum and Textbook Board 69-70, Motijheel Commercial Area, Dhaka-1000 [All rights reserved by the publisher] First edition: July, 2015 Revised edition: September, 2020 Design National Curriculum and Textbook Board Price: Tk. 88.00 (Eighty eight) Only Printed by: PREFACE This new English for Today textbook has been developed for classes 11 & 12 according to the National Curriculum 2012. A team of experienced writers and editors have worked hard to complete the writing and editing of this textbook. The process of rational evaluation of the manuscript was carried out by a group of educationists, teacher educators, experts of pedagogy, class-room teachers and NGO representatives under the guidance ofNCTB. The book is based on the principle that has guided the writing of the English for Today books from class 6 onwards- the principle of learning a language by actually practising it. This practice, which is carried out through the four language skills: speaking, listening, reading and writing, usually in an interactive mode, underlies the communicative approach to language learning. As the focus is on the communicative functions of language, the main aim of the textbook is to provide ample opportunities for students to use English for a variety of purposes in interesting situations. -

Situation of Youth in Bangladesh -.:: Natural Sciences Publishing

149 Int. J. Youth Eco. 1, No. 2, 149-155 (2017) DOI. http://dx.doi.org/10.18576/ijye/010204 Situation of Youth in Bangladesh Dulal Biswas* President- National Federation of Youth Organisations in Bangladesh, Bangladesh Received: 19 Aug. 2017, Revised: 19 Oct. 2017, Accepted: 20 Oct. 2017. Published online: 1 Nov. 2017. Abstracts This paper reviews the general conditions of youth in Bangladesh. Economic problems are reviewed in relevance to ruination of family values and its effect on youth. The researcher set an attempt to set out with the vision to start and build big businesses are mostly met with disappointments because the corruption level is unimaginably high and a budding entrepreneur. The paper discusses the donors agencies which started funding some entrepreneurial ventures. The paper goes on the influence of youth income, the workplace conditions and the degree of unemployment in high demand for jobs. The influence of IT development on the youth lifestyle is also covered along with modern demands. The paper give specific recommendations that would enhance education, employment, entrepreneurship and resource utilization. Key words: Youth, Bangladesh, Youth Economy, NGOs Introduction At the beginning it must be mentioned that in Bangladesh we are facing lot of contradictions and economic phenomena is often confusing and difficult to explain. It is almost a paradoxical situation. On the one hand, the economy of Bangladesh is on an improving trend in reality in spite of quite a few negative indicators, while on the other hand, despite all the optimistic hype about the bright future of the youth of the country in general, the reality is not quite as fascinating. -

Editorial Board

A Professional Journal of National Defence College Volume 19 Number 1 June 2020 National Defence College Bangladesh EDITORIAL BOARD Chief Patron Lieutenant General Sheikh Mamun Khaled, SUP, rcds, psc, PhD Editor-in-Chief Rear Admiral M Shafiul Azam, NUP, ndc, psc Editor Colonel M A Saadi, afwc, psc Associate Editors Brigadier General Muhammad Ali Talukder, ndc, afwc, psc Lieutenant Colonel Muhammad Alamgir Iqbal Khan, psc, Arty Assistant Editors Assistant Professor Nishat Sultana Assistant Director Md Nazrul Islam ISSN: 1683-8475 DISCLAIMER The analysis, opinions and conclusions expressed or implied in this Journal are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NDC, Bangladesh Armed Forces or any other agencies of Bangladesh Government. Statement, fact or opinion appearing in NDC Journal are solely those of the authors and do not imply endorsement by the editors or publisher. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electrical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Published by the National Defence College, Bangladesh Design & Printed by : Isamoti Printers 89/3, Nayapaltan, Dhaka-1000, Bangladesh Cell: 01947540934, E mail: [email protected] CONTENTS Page Foreword v Editorial vi Abstracts vii Trans-boundary Water Sharing: A Comparative Analysis of Ganges Water Sharing Treaty 1996 and Few other Related International Treaties and Conventions for Identifying