Bangladesh and Violent Extremism: RESOLVE Network Research 2016-2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See Resource File

Prospects and Opportunities of International Cooperation in Attaining SDG Targets in Bangladesh (Global Partnership in Attainment of the SDGs) General Economics Division (GED) Bangladesh Planning Commission Ministry of Planning Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh September 2019 Prospects and Opportunities of International Cooperation in Attaining SDG Targets in Bangladesh Published by: General Economics Division (GED) Bangladesh Planning Commission Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Sher-e-Bangla Nagar, Dhaka-1207, Bangladesh Website: www.plancomm.gov.bd First Published: September 2019 Editor: Dr. Shamsul Alam, Member (Senior Secretary), GED Printed By: Inteshar Printers 217/A, Fokirapool, Motijheel, Dhaka. Cell: +88 01921-440444 Copies Printed: 1000 ii Bangladesh Planning Commission Message I would like to congratulate General Economics Division (GED) of the Bangladesh Planning Commission for conducting an insightful study on “Prospect and Opportunities of International Cooperation in Attaining SDG Targets in Bangladesh” – an analytical study in the field international cooperation for attaining SDGs in Bangladesh. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) agenda is an ambitious development agenda, which can’t be achieved in isolation. It aims to end poverty, hunger and inequality; act on climate change and the environment; care for people and the planet; and build strong institutions and partnerships. The underlying core slogan is ‘No One Is Left Behind!’ So, attaining the SDGs would be a challenging task, particularly mobilizing adequate resources for their implementation in a timely manner. Apart from the common challenges such as inadequate data, inadequate tax collection, inadequate FDI, insufficient private investment, there are other unique and emerging challenges that stem from the challenges of graduation from LDC by 2024 which would limit preferential benefits that Bangladesh have been enjoying so far. -

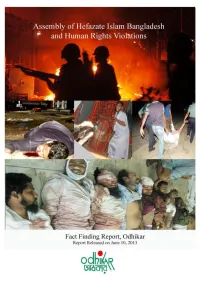

Odhikar's Fact Finding Report/5 and 6 May 2013/Hefazate Islam, Motijheel

Odhikar’s Fact Finding Report/5 and 6 May 2013/Hefazate Islam, Motijheel/Page-1 Summary of the incident Hefazate Islam Bangladesh, like any other non-political social and cultural organisation, claims to be a people’s platform to articulate the concerns of religious issues. According to the organisation, its aims are to take into consideration socio-economic, cultural, religious and political matters that affect values and practices of Islam. Moreover, protecting the rights of the Muslim people and promoting social dialogue to dispel prejudices that affect community harmony and relations are also their objectives. Instigated by some bloggers and activists that mobilised at the Shahbag movement, the organisation, since 19th February 2013, has been protesting against the vulgar, humiliating, insulting and provocative remarks in the social media sites and blogs against Islam, Allah and his Prophet Hazrat Mohammad (pbuh). In some cases the Prophet was portrayed as a pornographic character, which infuriated the people of all walks of life. There was a directive from the High Court to the government to take measures to prevent such blogs and defamatory comments, that not only provoke religious intolerance but jeopardise public order. This is an obligation of the government under Article 39 of the Constitution. Unfortunately the Government took no action on this. As a response to the Government’s inactions and its tacit support to the bloggers, Hefazate Islam came up with an elaborate 13 point demand and assembled peacefully to articulate their cause on 6th April 2013. Since then they have organised a series of meetings in different districts, peacefully and without any violence, despite provocations from the law enforcement agencies and armed Awami League activists. -

An Alternative Report to the Fifth State Party Periodic Report to UNCRC

An Alternative Report to the Fifth State Party Periodic Report to UNCRC State Party: Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Contact Information: Submitted By: Child Rights Advocacy Save the Children in Coalition in Bangladesh Bangladesh House-82, Road- 19A, Block-E, Banani Dhaka, Bangladesh Tel: +88-02-9861690, Fax: +88-02-9886372 Web: www.savethechildren.net 30th October 2014 Table of Contents PART I: GENERAL OVERVIEW AND INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 1 Background and Context ............................................................................................................................. 1 Objective of the Alternative Report ............................................................................................................ 1 Methodology .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Organization of the Alternative Report ...................................................................................................... 1 PART II: IMPLEMENTATION OF THE UNCRC IN BANGLADESH ........................................................ 2 3.3 Rights of children with disabilities and children belonging to minorities........................................ 8 4.3 Freedom of expression and right to seek, receive and impart information ................................. 11 4.4 Freedom of association and peaceful assembly............................................................................ -

In Their Own Words: Voices of Jihad

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as CHILD POLICY a public service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION Jump down to document ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT 6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and PUBLIC SAFETY effective solutions that address the challenges facing SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY the public and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Support RAND TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Purchase this document WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Learn more about the RAND Corporation View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND monographs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. in their own words Voices of Jihad compilation and commentary David Aaron Approved for public release; distribution unlimited C O R P O R A T I O N This book results from the RAND Corporation's continuing program of self-initiated research. -

Primary Education Finance for Equity and Quality an Analysis of Past Success and Future Options in Bangladesh

WORKING PAPER 3 | SEPTEMBER 2014 BROOKE SHEARER WORKING PAPER SERIES PRIMARY EDUCATION FINANCE FOR EQUITY AND QUALITY AN ANALYSIS OF PAST SUCCESS AND FUTURE OPTIONS IN BANGLADESH LIESBET STEER, FAZLE RABBANI AND ADAM PARKER Global Economy and Development at BROOKINGS BROOKE SHEARER WORKING PAPER SERIES This working paper series is dedicated to the memory of Brooke Shearer (1950-2009), a loyal friend of the Brookings Institution and a respected journalist, government official and non-governmental leader. This series focuses on global poverty and development issues related to Brooke Shearer’s work, including: women’s empowerment, reconstruction in Afghanistan, HIV/AIDS education and health in developing countries. Global Economy and Development at Brookings is honored to carry this working paper series in her name. Liesbet Steer is a fellow at the Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution. Fazle Rabbani is an education adviser at the Department for International Development in Bangladesh. Adam Parker is a research assistant at the Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution. Acknowledgements: We would like to thank the many people who have helped shape this paper at various stages of the research process. We are grateful to Kevin Watkins, a nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and the executive director of the Overseas Development Institute, for initiating this paper, building on his earlier research on Kenya. Both studies are part of a larger work program on equity and education financing in these and other countries at the Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution. Selim Raihan and his team at Dhaka University provided the updated methodology for the EDI analysis that was used in this paper. -

Splinter Terrorist Groups: Emerging Trends of Terrorism in Bangladesh

SPLINTER TERRORIST GROUPS: EMERGING TRENDS OF TERRORISM IN BANGLADESH Innovative new tactics have always been a tool of survival or expansion for terrorist www.bipss.org.bd groups all over the world. Activities of extremist/ terrorist groups in Bangladesh now appear to be following a new pattern. It seems that the older strategy of bigger group, rapid expansion of network and spectacular terrorist acts to capture immediate media and public attention has been abandoned for the time being due to its failure. Such tactics have also been excluded keeping in mind the strong reaction from the security apparatus and the negative public sentiments towards terrorism. The rise of rather smaller groups in disguise of various activities gives a new impression about the emerging trend. Police in Bangladesh recently unearthed activities of a small group named ‘Ansarullah Bangla Team’ (Volunteer of Allah Bangla Team). Their leader Mohammad Jasimuddin Rahmani was arrested with 30 of his followers on 15th August 2013. On the previous day police recovered huge volume of Jihadist literature, documents and list of persons to be killed through terror attacks. Similar recoveries along with some small arms were made on 24th of the same month in Barisal districts.Bangladesh Institute of Peace and Security Studies (BIPSS) predicted, in its previous publication,this emergence of splinter extremist/ terrorist groups. Background and Context Extremist/ terrorist phenomenon in Bangladesh came hand in hand with increased terrorist activities in the international arena. Home grown but internationally linked groups like JMB, Jagrata Muslim Janata Bangladesh (JMJB), Harkatul Jihad Al Islami – Bangladesh (HUJI-B) and others came to being in Bangladesh emerged in the late nineties and the early years of ther 21st century. -

Reforming the Education System in Bangladesh: Reckoning a Knowledge-Based Society

www.sciedu.ca/wje World Journal of Education Vol. 4, No. 4; 2014 Reforming the Education System in Bangladesh: Reckoning a Knowledge-based Society Md. Nasir Uddin Khan1, Ebney Ayaj Rana2,* & Md. Reazul Haque3 1Ministry of Primary and Mass Education, Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh, Bangladesh 2Unnayan Onneshan-A Center for Research and Action on Development based in Dhaka, Bangladesh 3Department of Development Studies, University of Dhaka, Bangladesh *Corresponding author: Unnayan Onneshan, 16/2, Indira Road, Farmgate, Dhaka-1215, Bangladesh. Tel: 880-172-505-2815. E-mail: [email protected] Received: April 15, 2014 Accepted: June 3, 2014 Online Published: June 25, 2014 doi:10.5430/wje.v4n4p1 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5430/wje.v4n4p1 Abstract Education renders people with certain capabilities that prepare them to contribute to the social and economic development of the nation. Such capabilities turn them into human capital which, according to development economists, raises productivity when increased. Following an exhaustive review of literature on education research, this paper, however, aims at exploring the effectiveness of Bangladesh’s present education system in delivering quality education as well as reckoning the prospect of establishing a knowledge-based society in the nation. This paper, being qualitative in nature, reveals that the nation has achieved an exemplary success in primary education as regards increased enrolment rate, while the enrolment rate is not satisfactory in secondary schooling and the tertiary education is expanding. However, the quality of education imparted at all the primary, secondary and tertiary levels is not up to the mark to create a strong human capital and reckon the prospect of knowledge-based society in the country. -

Bangladesh Other Countries and Regions Monitored

BANGLADESH OTHER COUNTRIES AND REGIONS MONITORED KEY FINDINGS RECOMMENDATIONS TO THE U.S. GOVERNMENT In 2016, the frequency of violent and deadly attacks against religious minorities, secular bloggers, intellec- USCIRF recommends that the U.S. government should: tuals, and foreigners by domestic and transnational provide technical assistance and encourage the Ban- extremist groups increased. Although the government, gladeshi government to further develop its national led by the ruling Awami League, has taken steps to inves- counterterrorism strategy; urge Prime Minister Sheikh tigate, arrest, and prosecute perpetrators and increase Hasina and all government officials to frequently and publicly denounce religiously divisive language and acts protection for likely targets, the threats and violence of religiously motivated violence and harassment; assist have heightened the sense of fear among Bangladeshi the Bangladeshi government in providing local govern- citizens of all religious groups. In addition, illegal land ment officials, police officers, and judges with training on appropriations—commonly referred to as land-grab- international human rights standards, as well as how to bing—and ownership disputes remain widespread, investigate and adjudicate religiously motivated violent particularly against Hindus and Christians. Other con- acts; urge the Bangladeshi government to investigate cerns include issues related to property returns and the claims of land-grabbing and to repeal its blasphemy law; situation of Rohingya Muslims. In March 2016, a USCIRF and encourage the Bangladeshi government to continue staff member traveled to Bangladesh to assess the reli- to provide humanitarian assistance and a safe haven for gious freedom situation. Rohingya Muslims fleeing persecution in Burma. BACKGROUND the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). -

Political Polarization and Religious Extremism in Bangladesh

April 30, 2015 Political Polarization and Religious Extremism in Bangladesh Prepared statement by Alyssa Ayres Senior Fellow for India, Pakistan, and South Asia Council on Foreign Relations Before the Committee on Foreign Affairs, Subcommittee on Asia and the Pacific United States House of Representatives 1st Session, 114th Congress Hearing on “Bangladesh’s Fracture: Political and Religious Extremism” Chairman Salmon, Ranking Member Sherman, and Members of the Subcommittee, Thank you very much for the invitation to appear before you on the critically important issue of political and religious extremism in Bangladesh. I am honored to be part of this distinguished panel, and am grateful that you have chosen to focus on this significant country, one that remains relatively under-studied. Bangladesh has been in the news for terrible reasons recently. On March 30 a young blogger, Washiqur Rahman, was hacked to death in Bangladesh's capital city, Dhaka. That attack came on the heels of a similar murder the month before: another blogger, an American citizen named Avijit Roy, was stabbed and hacked to death February 26 as he left the Dhaka book fair. Two years earlier, in 2013, a blogger named Ahmed Rajib Haider was attacked in Dhaka and hacked to death with machetes. All three were targeted by radical Islamists for holding atheist views and writing about them openly. As I have argued elsewhere, these assasinations have opened a new front between the values of a syncretic, secular, humanistic Bangladeshi culture against a rigid worldview incapable of allowing difference to coexist. These murders have been all the more troubling given Bangladesh’s comparative moderation and its well-known economic and development successes. -

CIFORB Country Profile – Bangladesh

CIFORB Country Profile – Bangladesh Demographics • Obtained independence from Pakistan (East Pakistan) in 1971 following a nine month civil uprising • Bangladesh is bordered by India and Myanmar. • It is the third most populous Muslim-majority country in the world. • Population: 168,957,745 (July 2015 est.) • Capital: Dhaka, which has a population of over 15 million people. • Bangladesh's government recognises 27 ethnic groups under the 2010 Cultural Institution for Small Anthropological Groups Act. • Bangladesh has eight divisions: Barisal, Chittagong, Dhaka, Khulna, Mymensingh, Rajshahi, Rangpur, Sylhet (responsible for administrative decisions). • Language: Bangla 98.8% (official, also known as Bengali), other 1.2% (2011 est.). • Religious Demographics: Muslim 89.1% (majority is Sunni Muslim), Hindu 10%, other 0.9% (includes Buddhist, Christian) (2013 est.). • Christians account for approximately 0.3% of the total population, and they are mostly based in urban areas. Roman Catholicism is predominant among the Bengali Christians, while the remaining few are mostly Protestants. • Most of the followers of Buddhism in Bangladesh live in the Chittagong division. • Bengali and ethnic minority Christians live in communities across the country, with relatively high concentrations in Barisal City, Gournadi in Barisal district, Baniarchar in Gopalganj, Monipuripara and Christianpara in Dhaka, Nagori in Gazipur, and Khulna City. • The largest noncitizen population in Bangladesh, the Rohingya, practices Islam. There are approximately 32,000 registered Rohingya refugees from Myanmar, and between 200,000 and 500,000 unregistered Rohingya, practicing Islam in the southeast around Cox’s Bazar. https://www.justice.gov/eoir/file/882896/download) • The Hindu American Foundation has observed: ‘Discrimination towards the Hindu community in Bangladesh is both visible and hidden. -

Human-Rights-Monitoring-Report-April

1 May 2018 Human Rights Monitoring Report 1-30 April 2018 Odhikar has, since 1994, been monitoring the human rights situation in Bangladesh in order to promote and protect civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights of Bangladeshi citizens and to report on violations and defend the victims. Odhikar does not believe that the human rights movement merely endeavours to protect the „individual‟ from violations perpetrated by the state; rather, it believes that the movement to establish the rights and dignity of every individual is part of the struggle to constitute Bangladesh as a democratic state. Odhikar has always been consistent in creating mass awareness of human rights issues using several means, including reporting violations perpetrated by the State and advocacy and campaign to ensure internationally recognised civil and political rights of citizens. The Organisation unconditionally stands by the victims of oppression and maintains no prejudice with regard to political leanings or ideological orientation, race, religion or sex. In line with this campaign, Odhikar prepares and releases human rights status reports every month. The Organisation has prepared and disseminated this human rights monitoring report of April 2018, despite facing persecution and continuous harassment and threats to its existence since 2013. Although many incidents of human rights violations occur every month, only a few significant incidents have been highlighted in this report. Information used in the report was gathered by human rights defenders -

Bangladesh 2017 1971 Assassinated Inamilitarycoup

1971 1971 War of independence from Pakistan. Bangladeshi authorities claim as many as 3 million deaths. 1975 Sheik Mujibur Rahman, founding president of Bangladesh, and most of his family are assassinated in a military coup. 1976 The indigenous, mostly Buddhist Jumma of the Chittagong Hill Tracts launch armed struggle against Bengali settlers and 1981 security forces. Former president Ziaur Rahman, of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), is assassinated in a military coup. 1991 End of military dictatorship and return to parliamentary democracy. 1997 Chittagong Hill Tracts Peace Accord is signed, but violence and Bengali settlement continue. There are 280,000 internally displaced people in CHT by January 2015. 2001 Postelection violence forces nearly 200,000 Hindus to flee or emigrate to India. 2004 Islamist group Huji-B attacks Awami League (AL) rally, killing 24 and injuring 2001 200, including former prime minister Catholic church bombing kills nine and Sheikh Hasina. injures 20. Religious minorities are increasingly targeted by violent Islamist groups. 2007 Military coup. Over 52,000 are arrested and 29 killed by law enforcement in the first month of the ensuing state of emergency. 2013 BNP boycotts tenth parliamentary elections, leading to armed violence, attacks on minorities, and hundreds of dead and 2008 injured. Ninth parliamentary elections, after nearly two years of military-backed caretaker government. 2013 Communal attacks on Hindu houses and shops follow death sentence for Islamist war 2014 criminal. Islamist party leader Abdul Quader Mollah executed for crimes during war 2013 of independence. Large-scale protests, First murders of secular bloggers by Islamic violence, and bombings ensue.