The Power of Using the Right to Information Act in Bangladesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See Resource File

Prospects and Opportunities of International Cooperation in Attaining SDG Targets in Bangladesh (Global Partnership in Attainment of the SDGs) General Economics Division (GED) Bangladesh Planning Commission Ministry of Planning Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh September 2019 Prospects and Opportunities of International Cooperation in Attaining SDG Targets in Bangladesh Published by: General Economics Division (GED) Bangladesh Planning Commission Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Sher-e-Bangla Nagar, Dhaka-1207, Bangladesh Website: www.plancomm.gov.bd First Published: September 2019 Editor: Dr. Shamsul Alam, Member (Senior Secretary), GED Printed By: Inteshar Printers 217/A, Fokirapool, Motijheel, Dhaka. Cell: +88 01921-440444 Copies Printed: 1000 ii Bangladesh Planning Commission Message I would like to congratulate General Economics Division (GED) of the Bangladesh Planning Commission for conducting an insightful study on “Prospect and Opportunities of International Cooperation in Attaining SDG Targets in Bangladesh” – an analytical study in the field international cooperation for attaining SDGs in Bangladesh. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) agenda is an ambitious development agenda, which can’t be achieved in isolation. It aims to end poverty, hunger and inequality; act on climate change and the environment; care for people and the planet; and build strong institutions and partnerships. The underlying core slogan is ‘No One Is Left Behind!’ So, attaining the SDGs would be a challenging task, particularly mobilizing adequate resources for their implementation in a timely manner. Apart from the common challenges such as inadequate data, inadequate tax collection, inadequate FDI, insufficient private investment, there are other unique and emerging challenges that stem from the challenges of graduation from LDC by 2024 which would limit preferential benefits that Bangladesh have been enjoying so far. -

An Alternative Report to the Fifth State Party Periodic Report to UNCRC

An Alternative Report to the Fifth State Party Periodic Report to UNCRC State Party: Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Contact Information: Submitted By: Child Rights Advocacy Save the Children in Coalition in Bangladesh Bangladesh House-82, Road- 19A, Block-E, Banani Dhaka, Bangladesh Tel: +88-02-9861690, Fax: +88-02-9886372 Web: www.savethechildren.net 30th October 2014 Table of Contents PART I: GENERAL OVERVIEW AND INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 1 Background and Context ............................................................................................................................. 1 Objective of the Alternative Report ............................................................................................................ 1 Methodology .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Organization of the Alternative Report ...................................................................................................... 1 PART II: IMPLEMENTATION OF THE UNCRC IN BANGLADESH ........................................................ 2 3.3 Rights of children with disabilities and children belonging to minorities........................................ 8 4.3 Freedom of expression and right to seek, receive and impart information ................................. 11 4.4 Freedom of association and peaceful assembly............................................................................ -

Annual Report 2019-2020

Annual Report 2019-2020 Palashipara Samaj Kallayan Samity (PSKS) Gangni, Meherpur annual report 2019-2020 1 BACKGROUND The organization named Palashipara Samaj Kallayan Samity (PSKS) was established as a Club by some enthusiastic youths of village Palashipara of Tentulbaria Union under Gangni Upazila of Meherpur District belonging to the south-east region of Bangladesh on 15 February 1970. The initiators were: 1) Md. Nazrul Islam (President), 2) Md. Suzauddin (Vice-President), 3) Md. Mosharrof Hossain (Secretary), 4) Md. Emdadul Haque (Treasurer), 5) Md. Rustom Ali (Subscription Collector), 6) Md. Abdul Aziz (Librarian), 7) Md. Zohir Uddin (Member), 8) Md. Abdul Jalil (Member), 9) Md. Abul Hossain (Member), 10) Md. Daulat Hossain (Member), 11) Md. Babur Ali (Member), 12) Md. Daud Hosain (Member), 13) Md. Nafar Uddin (Member), 14) Md. Golam Hossain (Mmeber), 15) Md. Ayeen Uddin (Member) and 16) Md. Mosharef Hossain (Mmeber). The organization came into being in concern of education and control of early marriage and exceeding population in the un-elevated and problematic area. The Club had no Office of its own till 1975. The Library was started in the wall-almirah in the reading room of the Founder Secretary Md. Mosharrof Hossain with personal endeavour of the members. Despite unwillingness, Md. Forman Ali built an office room in his own land adjacent to his house in 1975 and allowed to resume the club activities there. All the members built there a room with muddy walls and straw-shade with their physical labour. As the number of readers in the library was very poor, there started Adult Education Program voluntarily in 1975. -

Storm Surges and Coastal Erosion in Bangladesh - State of the System, Climate Change Impacts and 'Low Regret' Adaptation Measures

Storm surges and coastal erosion in Bangladesh - State of the system, climate change impacts and 'low regret' adaptation measures By: Mohammad Mahtab Hossain Master Thesis Master of Water Resources and Environmental Management at Leibniz Universität Hannover Franzius-Institute of Hydraulic, Waterways and Coastal Engineering, Faculty of Civil Engineering and Geodetic Science Advisor: Dipl.-Ing. Knut Kraemer Examiners: Prof. Dr.-Ing. habil. T. Schlurmann Dr.-Ing. N. Goseberg Submission date: 13.09.2012 Prof. Dr. Torsten Schlurmann Hannover, Managing Director & Chair 15 March 2012 Franzius-Institute for Hydraulic, Waterways and Coastal Engineering Leibniz Universität Hannover Nienburger Str. 4, 30167 Hannover GERMANY Master thesis description for Mr. Mahtab Hussein Storm surges and coastal erosion in Bangladesh - State of the system, climate change impacts and 'low regret' adaptation measures The effects of global environmental change, including coastal flooding stem- ming from storm surges as well as reduced rainfall in drylands and water scarcity, have detrimental effects on countries and megacities in the costal regions worldwide. Among these, Bangladesh with its capital Dhaka is today widely recognised to be one of the regions most vulnerable to climate change and its triggered associated impacts. Natural hazards that come from increased rainfall, rising sea levels, and tropical cyclones are expected to increase as climate changes, each seri- ously affecting agriculture, water & food security, human health and shelter. It is believed that in the coming decades the rising sea level alone in parallel with more severe and more frequent storm surges and stronger coastal ero- sion will create more than 20 million people to migrate within Bangladesh itself (Black et al., 2011). -

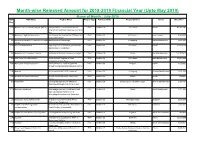

Upto May 2019) Name of Month : July-2018 NGO NGO Name Project Name Project Type Released Date Project District Sector Allocation Reg

Month-wise Released Amount for 2018-2019 Financial Year (Upto May 2019) Name of Month : July-2018 NGO NGO Name Project Name Project Type Released Date Project District Sector Allocation Reg. 2473 Medicins Sans Frontieres-Belgium (MSFB) Ukhiya the Host Community Outreach FD-6 2018-Jul-26 Cox's Bazar Health 83,062,387 Program and Outbreak Response Coxs bazar Dist 55 Madaripur Legal Aid Association Lets Cleanup the Country Day 2018 and Lets FD-6 2018-Jul-25 All Districts, Environment 6,000,000 Build Green Schools 135 Mohamuni Bidhaba-O-Anath Shishu Kalyan Maintenance of Orphanage FD-6 2018-Jul-22 Chittagong, Social Development 3,032,500 Kendra 2266 Nutrition International Operating Cost of Alleviating Micronutient FD-6 2018-Jul-01 All Districts, Health 45,604,296 Malnutrition in Bangladesh 665 Medecins Sans Frontieres - France Re-Launch of Mission Coordination Project FD-6 2018-Jul-28 Dhaka, Social Development 123,787,691 476 NGO Forum For Public Health WASH Support Program for Host FD-6 2018-Jul-28 Cox's Bazar Local Government 37,867,093 Community in Coxs Bazar 2997 Mafizuddin Nazeda Foundation Rural Community Health Programme FD-6 2018-Jul-09 Dinajpur, Health 1,100,000 through Mofizuddin Mazed Medical Centre 1181 Mamata HER Project-MAMATA(HER Finance) FD-6 2018-Jul-09 Chittagong, Women Development 5,691,289 1982 Mosabbir Memorial foundation Strenthening of Mosabbir Cancer Care FD-6 2018-Jul-09 Dhaka, Health 834,827 Centre 943 Naripokkho Claiming the Right to Safe Menstrual FD-6 2018-Jul-29 Dhaka, Barisal, Patuakhali, Bogra, Women Development -

The Millennium Development Goals

The Millennium Development Goals Bangladesh Progress Report 2009 General Economics Division Planning Commission Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh The Millennium Development Goals Bangladesh Progress Report 2009 General Economics Division Planning Commission Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh The Millennium Development Goals Progress Report 2009 has been benefited from the financial and technical assistance of the United Nations System in Bangladesh. The Millennium Development Goals The Millennium Development Goals Bangladesh Progress Report 2009 Design & Published by General Economics Division Planning Commission Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Bangladesh Progress Report 2009 Copies printed: 2500 Printed by Scheme Service Genesis (Pvt.) Ltd., Dhaka, Bangladesh The Millennium Development Goals Bangladesh Progress Report 2009 Message Air Vice Marshal (Retd.) A. K. Khandker The Millennium Development Goals Minister Ministry of Planning Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh I am happy to learn that the General Economics Division (GED) of the Bangladesh Planning Commission has prepared the `Millennium Development Goals: Bangladesh Progress Report 2009’ taking inputs from relevant ministries and related stakeholders along with the technical assistance from the UN Systems. As the coming Sixty-fifth session of the United Nations General Assembly, inter alia, will review the latest achievements of the MDGs, the report will be supportive to do the same for Bangladesh The Government of Bangladesh is committed to achieve the MDGs within the given timeframe and accordingly prepared an action plan. The National Strategy for Accelerated Poverty Reduction (NSAPR-1), the Medium Term Budgetary Framework (MTBF) and the Annual Development Programs (ADPs) have also been tuned towards achieving the MDGs. -

Department of Sociology University of Dhaka Dhaka University Institutional Repository

THE NATURE AND EXTENT OF HOMICIDE IN BANGLADESH: A CONTENT ANALYSIS ON REPORTS OF MURDER IN DAILY NEWSPAPERS T. M. Abdullah-Al-Fuad June 2016 Department of Sociology University of Dhaka Dhaka University Institutional Repository THE NATURE AND EXTENT OF HOMICIDE IN BANGLADESH: A CONTENT ANALYSIS ON REPORTS OF MURDER IN DAILY NEWSPAPERS T. M. Abdullah-Al-Fuad Reg no. 111 Session: 2011-2012 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Philosophy June 2016 Department of Sociology University of Dhaka Dhaka University Institutional Repository DEDICATION To my parents and sister Dhaka University Institutional Repository Abstract As homicide is one of the most comparable and accurate indicators for measuring violence, the aim of this study is to improve understanding of criminal violence by providing a wealth of information about where homicide occurs and what is the current nature and trend, what are the socio-demographic characteristics of homicide offender and its victim, about who is most at risk, why they are at risk, what are the relationship between victim and offender and exactly how their lives are taken from them. Additionally, homicide patterns over time shed light on regional differences, especially when looking at long-term trends. The connection between violence, security and development, within the broader context of the rule of law, is an important factor to be considered. Since its impact goes beyond the loss of human life and can create a climate of fear and uncertainty, intentional homicide (and violent crime) is a threat to the population. Homicide data can therefore play an important role in monitoring security and justice. -

57 47 01 096 2 *Banshbaria Dakshin Para 214 8.9 49.5 38.3 3.3 3.3

Table C-14: Percentage Distribution of General Households by Type of Structure,Toilet Facility, Residence and Community Type of Structure (%) Toilet Facility (%) Administrative Unit UN / MZ / Number of Sanitary ZL UZ Vill RMO Residence Sanitary (non WA MH Households Pucka Semi-pucka Kutcha Jhupri (water- Non-sanitary None Community water-sealed) sealed) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 57 Meherpur Zila Total 165974 20.0 33.4 43.4 3.1 20.2 25.4 46.5 7.9 57 1 Meherpur Zila 145631 18.0 32.6 46.1 3.4 17.5 25.7 48.2 8.6 57 2 Meherpur Zila 16704 36.6 40.8 21.1 1.5 43.2 24.8 29.6 2.4 57 3 Meherpur Zila 3639 27.6 33.0 38.8 0.7 24.0 15.5 53.8 6.7 57 47 Gangni Upazila Total 77470 15.1 42.2 39.8 2.9 15.3 24.2 51.9 8.6 57 47 1 Gangni Upazila 69866 13.8 41.1 42.1 3.0 12.9 24.3 53.6 9.1 57 47 2 Gangni Upazila 6441 28.6 52.1 17.6 1.7 39.9 24.1 31.8 4.2 57 47 3 Gangni Upazila 1163 15.6 56.7 26.2 1.5 21.6 18.2 56.8 3.4 57 47 Gangni Paurashava 6441 28.6 52.1 17.6 1.7 39.9 24.1 31.8 4.2 57 47 01 Ward No-01 Total 701 9.1 62.9 26.7 1.3 28.2 30.4 29.8 11.6 57 47 01 096 2 *Banshbaria Dakshin Para 214 8.9 49.5 38.3 3.3 3.3 18.2 60.3 18.2 57 47 01 097 2 *Banshbaria Paschimpara 110 9.1 63.6 25.5 1.8 44.5 41.8 4.5 9.1 57 47 01 098 2 *Banshbaria Uttarpara 192 9.9 66.7 23.4 0.0 47.9 32.3 5.7 14.1 57 47 01 329 2 *Banshbaria Purbapara 114 10.5 72.8 16.7 0.0 35.1 16.7 44.7 3.5 57 47 01 337 2 *Jhinirpul Para 71 5.6 76.1 18.3 0.0 14.1 66.2 18.3 1.4 57 47 02 Ward No-02 Total 829 31.1 45.8 22.4 0.6 48.3 21.5 26.5 3.7 57 47 02 298 2 *Chuagachha Cinema Hallpara 149 54.4 43.0 2.7 0.0 -

Investigation on Anthrax in Bangladesh During the Outbreaks of 2011 and Definition of the Epidemiological Correlations

pathogens Article Investigation on Anthrax in Bangladesh during the Outbreaks of 2011 and Definition of the Epidemiological Correlations Domenico Galante 1 , Viviana Manzulli 1,* , Luigina Serrecchia 1, Pietro Di Taranto 2, Martin Hugh-Jones 3, M. Jahangir Hossain 4,5, Valeria Rondinone 1, Dora Cipolletta 1, Lorenzo Pace 1 , Michela Iatarola 1, Francesco Tolve 1, Angela Aceti 1, Elena Poppa 1 and Antonio Fasanella 1 1 Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale of Puglia and Basilicata, Anthrax Reference Institute of Italy, 71121 Foggia, Italy; [email protected] (D.G.); [email protected] (L.S.); [email protected] (V.R.); [email protected] (D.C.); [email protected] (L.P.); [email protected] (M.I.); [email protected] (F.T.); [email protected] (A.A.); [email protected] (E.P.); [email protected] (A.F.) 2 Servizio Igiene degli Allevamenti e delle Produzioni Zootecniche—Asl 02 Abruzzo Lanciano—Vasto-Chieti, 66054 Vasto, Italy; [email protected] 3 Department of Environmental Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803-5705, USA; [email protected] 4 International International Centre for Diarrheal Disease Research, Programme on Infectious Diseases & Vaccine Sciences, Health System & Infectious Disease Division, Bangladesh (ICDDR,B), 1212 Dhaka, Bangladesh; [email protected] 5 Medical Research Council Unit The Gambia at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, 273 Banjul, The Gambia * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-0881786330 Citation: Galante, D.; Manzulli, V.; Serrecchia, L.; Taranto, P.D.; Abstract: In 2011, in Bangladesh, 11 anthrax outbreaks occurred in six districts of the country. -

Positive Engagement for Sustainable Development

POSITIVE ENGAGEMENT FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT ANNUAL REPORT 2018 *6(:;^HZVULVM[OLÄYZ[HUKMHZ[ YLZWVUKLYZ[V[OL9VOPUN`H/\THUP[HYPHU JYPZPZ*6(:;O\THUP[HYPHUYLZWVUZLZ PUJS\KL[OYLL[`WLZVMHJ[P]P[PLZZ\JOHZH WYV]PKPUNLTLYNLUJ`Z\WWVY[ZSPRLMVVK HUKUVUMVVKP[LTZKPZ[YPI\[PVULK\JH[PVU OLHS[OJHYLZ\WWVY[^VTLUHUKJOPSKYLU JHYLL[J(SS[OLHJ[P]P[PLZ^LYLK\S` HWWYV]LKI`[OLNV]LYUTLU[I3VJHS UH[PVUHSHUKPU[LYUH[PVUHSSL]LSHK]VJHJ` HUKJHTWHPNU[VW\[WYLZZ\YLVU4`HUTHY MVYPTTLKPH[LYLWH[YPH[PVUHUKJ3VJHS UH[PVUHSHUKPU[LYUH[PVUHSSL]LSJHTWHPNUZ HUKHK]VJHJ`MVY[OLWYVTV[PVUVM SVJHSPaH[PVUVMO\THUP[HYPHUHPK0UULY JV]LYZVM*6(:;(UU\HS9LWVY[ PZZOV^JHZPUNZVTLWOV[VZVM*6(:; O\THUP[HYPHUYLZWVUZLZ[V[OL9VOPUN`H *YPZPZ Acronyms annual AFA: Asian Farmers Association GBV: Gender Based Violation BDT: Bangladeshi Taka LNGO: Local NGOs report 2018 report C4C: Charter for Change MBBS: Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery CBCPC: Community Based Child Protection Committee MDGs: Millennium Development Goals CBOs: Community Based Organizations MF: Micro Finance CCNF: Cox’s Bazar CSOS NGOs Forum MJF: Manusher Jonno Foundation CDO: Credit and Development Officer MT: Metric Ton CFTM: Climate Finance Transparency MTCP: Medium Term Cooperation Project Mechanism NGO: Non-Governmental Organization CITEP: Coastal Integrated Technology Extension Program NRC: Norwegian Refugee Council CJRF: Climate Justice Resilience Fund NVF: New Venture Fund CMC: Centre Management Committee NWDP: National Women’s Development Policy COAST: Coastal Association for Social Transformation Trust PACE: Promotion Agricultural -

জেলা পরিসংখ্যান ২০১১ কক্সবাজার District Statistics 2011 Cox's Bazar

জেলা পরিসংখ্যান ২০১১ কক্সবাজার District Statistics 2011 Cox’s Bazar December 2013 BANGLADESH BUREAU OF STATISTICS (BBS) STATISTICS AND INFORMATICS DIVISION (SID) MINISTRY OF PLANNING GOVERNMENT OF THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF BANGLADESH District Statistics 2011 Cox’s Bazar District District Statistics 2011 Published in December, 2013 Published by : Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) Printed at : Reproduction, Documentation and Publication (RDP) Section, FA & MIS, BBS Cover Design: Chitta Ranjon Ghosh, RDP, BBS ISBN: For further information, please contract: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) Statistics and Informatics Division (SID) Ministry of Planning Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Parishankhan Bhaban E-27/A, Agargaon, Dhaka-1207. www.bbs.gov.bd COMPLIMENTARY This book or any portion thereof cannot be copied, microfilmed or reproduced for any commercial purpose. Data therein can, however, be used and published with acknowledgement of the sources. ii District Statistics 2011 Cox’s Bazar District Foreword I am delighted to learn that Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) has successfully completed the ‘District Statistics 2011’ under Medium-Term Budget Framework (MTBF). The initiative of publishing ‘District Statistics 2011’ has been undertaken considering the importance of district and upazila level data in the process of determining policy, strategy and decision-making. The basic aim of the activity is to publish the various priority statistical information and data relating to all the districts of Bangladesh. The data are collected from various upazilas belonging to a particular district. The Government has been preparing and implementing various short, medium and long term plans and programs of development in all sectors of the country in order to realize the goals of Vision 2021. -

Country Youth Prof Ile - Bangladesh

Country Youth Prof ile - Bangladesh Country Youth Prof ile BANGLADESH Women and Youth Empowerment Division Resilience and Social Development Department February 201 1 1. Socio-economic Profile 1.1. The People’s Republic of Bangladesh is located on the North-eastern part of South Asia, with a projected pop- ulation of 167,414.566 in 20191. The country experienced a steady economic growth rate between 2010-2017 with its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) averaging over 6% annually reaching a peak of 7.3% in 2017, the highest in the country’s history2. Bangladesh has made remarkable progress in reducing poverty. The population living below the national poverty line dropped from 31.5% in 2010 to 24.3% in 20163. The proportion of the employed living below the $1.90 purchasing power parity (PPP) a day dropped from 44.2% in 1991 to14.8% in 2016/20174. In parallel, the country achieved a lower middle-income status in 2015 and qualified for graduation from a Least Developing Coun- try in March 2018 and is on track for graduation in 20245. 1.2 Bangladesh’s position on the United Nations Development Program’s (UNDP) 2017 Human Development Index (HDI) moved up three positions from its 2016 rank of 139th to 136th out of 189 countries6. However, Bangladesh’s HDI of 0.608 is below the average of 0.631 and 0.645 for the medium human development category and South Asian countries respectively7. 1.3. The official characterization of youth in Bangladesh refers to persons between ages 18-35. However, the youth data from the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) is based on the 15-29-years age range.