NEDIAS Newsletter No 65 February 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Countryside Destination Events – Autumn 2018

Countryside Destination Events – Autumn 2018 Elvaston Castle Sat 1st – 7-9pm The Park in the Dark – Come meet the night time Elvaston Castle, Thurs 6th Sep residents! Learn about hedgehogs, birds and bats on this Borrowash Road, family friendly stroll around the grounds. 2 Miles. Bring a Elvaston, Derby, torch! Cost: Adults - £6, Children - £4 DE72 3EP Book: www.derbyshire.gov.uk/countrysideevents Sat 22nd – Sun 10am- Woodland Festival – celebrate traditional and “ 23rd Sep 5pm contemporary woodland crafts. Lots of family activities, (turn up local food, crafts, arts, gifts. Bushcraft, firelighting, etc! anytime) £10 per car parking charges/ £15 per car for weekend www.derbyshire.gov.uk/woodlandfestival Sat 27th Oct 6pm- Gruesome Tales – spine tingling stories as we explore the “ 8pm castle at night! Visit ghostly gothic hall then fill up with freeky food in Wyatts Café. Less than 2 miles. Fancy dress welcome! Cost: Adults - £15, Children - £8 Book: www.derbyshire.gov.uk/countrysideevents Wed 31st Oct 10:30am- Pumpkin Party! – Head to the courtyard to visit the “ 3pm pumpkin parlour. Carve your own pumpkin to take home. Trail sheets to explore the grounds – watch out for scary surprises, return to the start to claim your prize! Less than a mile walk, spooky fancy dress welcome. £2 per trail sheet Sat 17th + Fri 7pm – The sky’s the limit – star gazing, look through high “ 30th Nov 9pm powered telescopes and learn all about the solar system. Hot drinks available whilst you gaze. Cost: Adults - £6, Children - £4 to include drinks Book: www.derbyshire.gov.uk/countrsideevents Shipley Country Park Sat 15th Sep 10- Launch and guided walk – The launch of the 30 walks, Shipley Country 10:30am walking festival. -

Beaufort Herald2011 Iss3

Beaufort Herald Beaufort Companye Newsletter March 2011 Volume 5, Issue 3 Now is the time to make sure you kit fits and is fixed Sir Richard Tunstall 2 hobby that I have seen. Well done to all of you that did appear, you were a Codnor Castle 3 –4 credit to the hobby and to the Beauforts. Also worth remembering they were Heworth Moor 5 filming all around our camp for the en- tire weekend so where will the rest of Angels of Mons 6 Still from Time Team Special the footage end up, suggestions anyone? JAYNE E .. 600 the revolt ...PT3 7 I take it that everyone has heard of or Fatal Colours 8 saw the Time Team Special on the Wars of the Roses, If you haven’t here is the Towton Guns 8 link to 4oD http://www.channel4.com/programm Cooks corner 8 es/time-team-specials/4od#3173822 You can then play “spot the reenactors I know” and freeze frame who's that? In the next issue: The program manages to create the ♦ Beaufort babes right atmosphere and was a credit to all ♦ “Sumer is icumen “ the reenactors taking part as it is one of ♦ Archers at events the best pieces of publicity for our “That’s my snickers you bounder!” ♦ Battle of Piltown Yorvik festival Asked if we will come back next year for the Yor- Next Issue— April 2011 On Friday 24th Feb several of vik Festival and also to us ably assisted by some Sav- stage a medieval event in iles and KIBS staged a pres- York in August of 2012 entation on the military side of the Wars of the Roses. -

The Chartist Movement from Different Perspectives 9

Mill Waters Parks and Reservoir Education pack Social unrest and the law in Sutton in the 1800s SUPPORTED BY millwaters.org.uk Contents Welcome 1 Social unrest and the law in Sutton in the 1800s 2 Key Stage 1 Task 1: Discuss whether the actions of the Luddites were right or wrong 4 Task 2: Protest songs to promote the cause 5 Task 3: I predict a riot! 6 Key Stage 2 Task 1: Was the reaction to the Chartist uprisings over the top? 7 Task 2: Role play a Radical leader giving a rousing speech 8 Task 3: Write about the Chartist movement from different perspectives 9 Worksheets Worksheet 1: The Industrial Revolution in Sutton 10 Worksheet 2: Radical thinking 11 Worksheet 3: The Luddites 12 Worksheet 4: The Chartist Movement 16 Worksheet 5: Edward Unwin 18 Curriculum links 22 Welcome This education pack aims to help you get more out of your visit to Mill Waters Heritage Centre. It provides a selection of different We have included Teacher’s tips tasks for you to choose from. It to give a deeper understanding aims to make learning about the of an issue. We recognise the site’s history in relation to social skill of teachers in being able to unrest in the 1800s in a fun and tailor the activities to meet the engaging way. objectives of their visit and to suit pupils and ability. The time needed for each activity is an indication only and may There are also supplementary vary depending on the size of your historical resources, such as group and how fully you explore newspaper extracts, letters and various topics. -

Ironville & Codnor Park Newsletter

Ironville & Codnor Park Newsletter Local news, events, articles and more. October 2019 Welcome to Issue Number Eleven We hope that you continue to find our village newsletter of interest and enjoy its articles and other contents. If you would like to get in touch please write to the editor - Andy ([email protected]) This Newsletter came to you via “Unicorns,” a local voluntary group celebrating and promoting the rich heritage and culture of our village through social events and effective communication. For further information why not visit our web site: http://unicorns.comli.com/Index.htm News From Ironville and CODNOR CASTLE EVENTS Codnor Park Primary School Open every second Sunday of each month 11am until 3pm 01773 602936 What a whirlwind summer term we have ALL WELCOME. On offer are guided tours of the castle, had! This half term started with the with refreshments, battle re enactment training with fabulous news that Mrs Grundy, our medieval Team Falchion, children's activities, dressing up Head teacher, had given birth to a beau- costumes and much more. This is a great opportunity to tiful baby girl, Martha Rose. learn more about the history of this very special castle, once Our Year Six pupils have been busy with their transition days in their new visited by kings and the powerful De Grey family who once school as well as completing fabulous lived there. (Sorry no parking). art projects of their choice. Merchandise is also for sale: the Codnor Castle booklet, replica gold noble coins, tea towels, fridge magnets and key rings. Private booking are available for We have been involved in numerous groups, schools and colleges. -

Derby Museums Collections Development Policy 2014

Derby Museums Collections Development Policy 2014 Name of museum: Derby Museums (comprising Derby Museum and Art Gallery, The Silk Mill and Pickford’s House) Name of governing body: Derby Museums Trust Date on which this policy was approved by governing body: November 2014 Policy review procedure: The collections development policy will be published and reviewed from time to time, at least once every five years. Date at which this policy is due for review: 2019 Arts Council England will be notified of any changes to the collections development policy, and the implications of any such changes for the future of collections. 1. Relationship to other relevant policies/plans of the organisation: 1.1. The museum’s statement of purpose is: The vision for Derby Museums is to shape the way in which Derby is understood, the way in which the city projects itself, the way in which people from all places are inspired to see themselves as the next generation of innovators, makers and creators. The purpose of Derby Museums is to inspire people to become part of a living story of world class creativity, innovation and making. 1.2. The governing body will ensure that both acquisition and disposal are carried out openly and with transparency. 1.3. By definition, the museum has a long-term purpose and holds collections in trust for the benefit of the public in relation to its stated objectives. The governing body therefore accepts the principle that sound curatorial reasons must be established before consideration is given to any acquisition to the collection, or the disposal of any items in the museum’s collection. -

The Library of Sir Geoffrey Bindman Part II 2020/10 Natural History

THE LIBRARY OF GEOFFREY BINDMAN PART III THE NINETEENTH CENTURY AND AFTER BERNARD QUARITCH LTD 36 Bedford Row, London, WC1R 4JH tel.: +44 (0)20 7297 4888 fax: +44 (0)20 7297 4866 email: [email protected] / [email protected] web: www.quaritch.com Bankers: Barclays Bank PLC, 1 Churchill Place, London E14 5HP Sort code: 20-65-90 Account number: 10511722 Swift code: BUKBGB22 Sterling account: IBAN: GB71 BUKB 2065 9010 5117 22 Euro account: IBAN: GB03 BUKB 2065 9045 4470 11 U.S. Dollar account: IBAN: GB19 BUKB 2065 9063 9924 44 VAT number: GB 322 4543 31 Recent lists: 2021/01 The Wandering Lens: Nineteenth-Century Travel Photography 2020/11 The Library of Sir Geoffrey Bindman Part II 2020/10 Natural History Recent catalogues: 1443 English Books & Manuscripts 1442 The English & Anglo-French Novel 1740-1840 1441 The Billmyer–Conant Collection — Hippology © Bernard Quaritch 2021 1. ANDREWS, Alexander. The History of British Journalism, from the Foundation of the Newspaper Press in England, to the Repeal of the Stamp Act in 1855, with Sketches of Press Celebrities … with an Index. London, R. Clay for Richard Bentley, 1859. 2 vols, 8vo, pp. viii, 339, [1];[ 4], 365, [1]; very short marginal tear to title of vol. I; a very good set in publisher’s red grained cloth by Westley’s & Co, London, boards blocked in blind, spines lettered in gilt; spines sunned, slight rubbing and bumping; modern booklabel of John E.C. Palmer to upper pastedowns. £150 First edition of a detailed study of British newspapers. The first comprehensive history of the subject, the text is derived from close study of the British Museum’s collections, from the sixteenth century to the mid-nineteenth. -

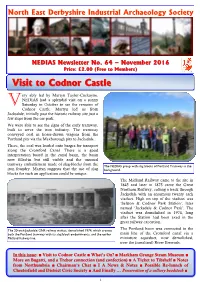

Visit to Codnor Castle

North East Derbyshire Industrial Archaeology Society NEDIAS Newsletter No. 64 – November 2016 Price: £2.00 (Free to Members) VisitVisit toto CodnorCodnor CastleCastle ery ably led by Martyn Taylor-Cockayne, V NEDIAS had a splendid visit on a sunny Saturday in October to see the remains of Codnor Castle. Martyn led us from Jacksdale, initially past the historic railway site just a few steps from the car park. We were able to see the signs of the early tramway, built to serve the iron industry. The tramway conveyed coal in horse-drawn wagons from the Portland pits via the Mexborough pits to Jacksdale. There, the coal was loaded onto barges for transport along the Cromford Canal. There is a good interpretation board in the canal basin, the basin now filled-in but still visible and the unusual tramway embankment made of slag-blocks from the The NEDIAS group with slag blocks of Portland Tramway in the iron foundry. Martyn suggests that the use of slag background. blocks for such an application could be unique. The Midland Railway came to the site in 1845 and later in 1875 came the Great Northern Railway, cutting a track through Jacksdale with an enormous twenty arch viaduct. High on top of the viaduct was ‘Selston & Codnor Park Station’, later named ‘Jacksdale & Codnor Park’. The viaduct was demolished in 1974, long after the Station had been axed in the great railway execution. The 20-arch Jacksdale GNR railway viaduct, demolished 1974, which crosses The Portland basin was connected to the both the Portland tramway with its slag block embankments, and the earlier main line of the Cromford canal via a Midland Railway line. -

Walking in Derbyshire

WALKING IN DERBYSHIRE by Elaine Burkinshaw JUNIPER HOUSE, MURLEY MOSS, OXENHOLME ROAD, KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA9 7RL www.cicerone.co.uk © Elaine Burkinshaw 2003, 2010 CONTENTS Second edition 2010 ISBN 978 1 85284 633 6 Reprinted 2013, 2017 and 2019 (with updates) Overview map ...................................................................................................5 Preface ..............................................................................................................7 First edition 2003 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................9 Geology ..........................................................................................................10 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. History ............................................................................................................12 Printed by KHL Printing, Singapore The shaping of present-day Derbyshire ............................................................22 Customs ..........................................................................................................28 This product includes mapping data licensed from Ordnance How to use this guide ......................................................................................30 Survey® with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. © Crown copyright 2010. All rights reserved. THE WALKS Licence number PU100012932 1 Creswell Crags ......................................................................................31 -

A Local History of Ironville & Codnor Park

A Local History of Ironville & Codnor Park 1 In the Beginning Before Ironville or Codnor Park there was a place called Smithycote. Smithycote was a settlement in the Codnor Park area, mentioned in the Domesday Book. The names of the Anglo Saxon residents and other information is also detailed. Now “long lost” probably “disappearing” when Codnor Castle was constructed and the surrounding parkland developed. Codnor Park including what is now known as The Forge was set up by the de Grey family who were granted the area by William the Conqueror. For their part in the Norman Conquest of England Close to the village is one of only two medieval castles retaining its original medieval architecture in the whole of the county of Derbyshire, (the only other being Peveril Castle in the Peak District). Codnor Castle has a very rich history and the castle site dates back to the 12th century. The castle was the home and power base for one of medieval England’s most powerful families for 300 years - the De Grey family, also known as the Baron's Grey of Codnor. This medieval fortress was once grand enough to play host to royal visits including that of King Edward II in 1342. The Castle is open to the Public every second Sunday of the month throughout the year. The de Greys were loyal to the King whoever he was (they fought for Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth and ingratiated themselves to the victor Henry VII, and so their castle survived when others such as Duffield Castle were destroyed in 1267 after the 2nd Barons War. -

The Pentrich Rebellion – a Nottingham Affair?

1 The Pentrich Rebellion – A Nottingham Affair? Richard A. Gaunt Department of History, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK Department of History, School of Humanities, University Park, Nottingham, NG7 2RD [email protected] Richard A. Gaunt is Associate Professor in Modern British History at the University of Nottingham. 2 The Pentrich Rebellion – A Nottingham Affair? This article re-considers Nottingham’s role in the events immediately preceding the Pentrich Rebellion of 9-10 June 1817, as well as its reaction on the night of the Rebellion and during its aftermath. It does so in light of two continuing areas of historiographical debate: Nottingham’s status as a radical, potentially revolutionary, town, and the Rebellion’s links to Luddism. Nottingham loomed large in the planning and course of the Rebellion; it was heavily influenced by the work of a secret committee centred on Nottingham, the North Midlands Committee, which provided essential points of contact with the villages at the heart of the Rebellion. It was also a Rebellion led by a Nottingham man, Jeremiah Brandreth, ‘the Nottingham Captain’. However, the effective role played by Nottingham Corporation, in treading the fine line between revolution and reaction, the inability of the radicals to persuade would-be rebels that they had an effective plan, and the ability of the local magistrates and the Home Office to gather intelligence about the Rebellion, all worked against it. The chances of a successful reception in Nottingham were always much lower than the Rebels anticipated. Keywords: Nottingham: Jeremiah Brandreth: Luddism: Duke of Newcastle: Oliver the Spy Late in the evening of Monday 9 June 1817, some 50-60 men set out from the villages of Pentrich and South Wingfield in Derbyshire on a fourteen-mile march towards Nottingham. -

Jeremiah Brandreth – the 'Nottingham Captain'

2nd edition March 2017 Free Spring 2 2017 Jeremiah Brandreth – the ‘Nottingham Captain’ Meet the man who led the march of the Revolutionaries. Brandreth was born in London and was baptised at St Andrews Pentrich 2017 wins Heritage Holborn on June 26, 1785. The Lottery Fund support Brandreth family moved to Barnstaple, Devon, in 1786. We have received £66,000 from When he was about 13 the the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) family moved to Exeter and set for our exciting project. Pentrich up a framework knitting 2017 aims to commemorate the business. bi-centenary of the last and little In 1803 he was listed as a known ‘revolution’ in the United reservist in the 28th Regiment of Kingdom. foot and in the same year was This ambitious project is centred present at the execution of Colonel Despard and six in the Amber Valley a nd adjacent areas in Derbyshire and guardsmen in London. A spectacle which drew 20,000 - Nottinghamshire and will run from the largest crowd until Nelson's April 1 st 2017 – December 31 st funeral. He deser ted from the 201 8 but provide a lasting and army around 1808. long overdue legacy for this momentous but largely forgotten In 1809 and 1811 his mother and historical event. then his father died. He moved to Sutton-in-Ashfield , where he had Commenting on the award, John a wife and two children. His Hardwick, Chair of the Organising Jeremiah Brandreth was not pregnant wife later walked from from the local area of Pentrich Sutton in Ashfield to visit him in Committee said; “We are thrilled and South Wingfield. -

Historic Env Assessments of Potential Housing Sites 2016/17

AMBER VALLEY BOROUGH COUNCIL DRAFT LOCAL PLAN Historic Environment Assessments of Potential Housing Sites 2016-17 Historic Environment Assessments Of Potential Housing Sites 2016-17 Each of the potential sites that the Borough Council has considered in the preparation of the Draft Local Plan has been subject to an assessment of the impact that residential development would have on the on the historic environment. The assessments have been used to inform the process of selecting the proposed Housing Growth Sites in the Draft Local Plan, as well as the Draft Sustainability Appraisal Report which accompanies the Draft Local Plan. The sites have been assessed with regard to the Historic England Guidance, which includes the following:- Historic Environment Good Practice Advice in Planning Note 2 - Managing Significance in Decision-Taking in the Historic Environment (2015) Historic England’s Guidance Note 3 -The Historic Environment and Site Allocations in Local Plans (2015) The Setting of Heritage Assets - Historic Environment Good Practice Advice in Planning: 3 (2015) Conservation Principles Policies and Guidance (2008). Please note that the site numbers referred to in the assessments (e.g. PHS001) as those set out in Appendix 6: Site Appraisals in the Draft Sustainability Appraisal Report – Technical Appendices. The following abbreviations have been used throughout the assessments:- DVMWHS – Derwent Valley Mills World Heritage Site HER – Historic Environment Record OUV – Outstanding Universal Value PHS – Potential Housing Site UNESCO