Dwindling Popularity Or a New Chapter?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

{DOWNLOAD} Ethics of Sport and Athletics 1St Edition Ebook

ETHICS OF SPORT AND ATHLETICS 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Robert C Schneider | --- | --- | --- | 9780781787918 | --- | --- Sports Giants: Athletes Who Tower Over the Competition Sports scientists and physicians, regulatory officials, athletes, bioethicists, and all others with an interest in the impact of drugs on sports and society. We are always looking for ways to improve customer experience on Elsevier. We would like to ask you for a moment of your time to fill in a short questionnaire, at the end of your visit. If you decide to participate, a new browser tab will open so you can complete the survey after you have completed your visit to this website. Thanks in advance for your time. About Elsevier. Set via JS. However, due to transit disruptions in some geographies, deliveries may be delayed. View on ScienceDirect. Serial Editor: Theodore Friedmann. Editor: Angela Schneider. Hardcover ISBN: Imprint: Academic Press. Published Date: 6th March Page Count: View all volumes in this series: Advances in Genetics. For regional delivery times, please check When will I receive my book? Sorry, this product is currently out of stock. Flexible - Read on multiple operating systems and devices. In , Venus Williams appealed to the Grand Slam governing board and then wrote an op-ed, fighting for equal monetary awards for men and women at Wimbledon and the French Open. Meanwhile, Serena Williams has vowed to fight for equal pay too — especially for Black women. Unlike the NFL, the NBA has a written rule about standing for the national anthem — and the league made sure to remind players of this stipulation. -

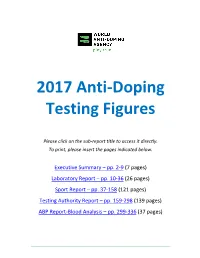

2017 Anti-Doping Testing Figures Report

2017 Anti‐Doping Testing Figures Please click on the sub‐report title to access it directly. To print, please insert the pages indicated below. Executive Summary – pp. 2‐9 (7 pages) Laboratory Report – pp. 10‐36 (26 pages) Sport Report – pp. 37‐158 (121 pages) Testing Authority Report – pp. 159‐298 (139 pages) ABP Report‐Blood Analysis – pp. 299‐336 (37 pages) ____________________________________________________________________________________ 2017 Anti‐Doping Testing Figures Executive Summary ____________________________________________________________________________________ 2017 Anti-Doping Testing Figures Samples Analyzed and Reported by Accredited Laboratories in ADAMS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This Executive Summary is intended to assist stakeholders in navigating the data outlined within the 2017 Anti -Doping Testing Figures Report (2017 Report) and to highlight overall trends. The 2017 Report summarizes the results of all the samples WADA-accredited laboratories analyzed and reported into WADA’s Anti-Doping Administration and Management System (ADAMS) in 2017. This is the third set of global testing results since the revised World Anti-Doping Code (Code) came into effect in January 2015. The 2017 Report – which includes this Executive Summary and sub-reports by Laboratory , Sport, Testing Authority (TA) and Athlete Biological Passport (ABP) Blood Analysis – includes in- and out-of-competition urine samples; blood and ABP blood data; and, the resulting Adverse Analytical Findings (AAFs) and Atypical Findings (ATFs). REPORT HIGHLIGHTS • A analyzed: 300,565 in 2016 to 322,050 in 2017. 7.1 % increase in the overall number of samples • A de crease in the number of AAFs: 1.60% in 2016 (4,822 AAFs from 300,565 samples) to 1.43% in 2017 (4,596 AAFs from 322,050 samples). -

This Sporting Life: Sports and Body Culture in Modern Japan William W

Yale University EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale CEAS Occasional Publication Series Council on East Asian Studies 2007 This Sporting Life: Sports and Body Culture in Modern Japan William W. Kelly Yale University Atsuo Sugimoto Kyoto University Follow this and additional works at: http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ceas_publication_series Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kelly, William W. and Sugimoto, Atsuo, "This Sporting Life: Sports and Body Culture in Modern Japan" (2007). CEAS Occasional Publication Series. Book 1. http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ceas_publication_series/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Council on East Asian Studies at EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in CEAS Occasional Publication Series by an authorized administrator of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This Sporting Life Sports and Body Culture in Modern Japan j u % g b Edited by William W. KELLY With SUGIMOTO Atsuo YALE CEAS OCCASIONAL PUBLICATIONS VOLUME 1 This Sporting Life Sports and Body Culture in Modern Japan yale ceas occasional publications volume 1 © 2007 Council on East Asian Studies, Yale University All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permis- sion. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. -

Ranking 2018 Po Zaliczeniu 120 Dyscyplin

RANKING 2018 PO ZALICZENIU 120 DYSCYPLIN OCENA PKT. ZŁ. SR. BR. SPORTS BEST 1. Rosja 238.5 1408 219 172 187 72 16 2. USA 221.5 1140 163 167 154 70 18 3. Niemcy 185.0 943 140 121 140 67 7 4. Francja 144.0 736 101 107 118 66 4 5. Włochy 141.0 701 98 96 115 63 8 6. Polska 113.5 583 76 91 97 50 8 7. Chiny 108.0 693 111 91 67 35 6 8. Czechy 98.5 570 88 76 66 43 7 9. Kanada 92.5 442 61 60 78 45 5 10. Wielka Brytania / Anglia 88.5 412 51 61 86 49 1 11. Japonia 87.5 426 59 68 54 38 3 12. Szwecja 84.5 367 53 53 49 39 3 13. Ukraina 84.0 455 61 65 81 43 1 14. Australia 73.5 351 50 52 47 42 3 15. Norwegia 72.5 451 66 63 60 31 2 16. Korea Płd. 68.0 390 55 59 52 24 3 17. Holandia 68.0 374 50 57 60 28 3 18. Austria 64.5 318 51 34 46 38 4 19. Szwajcaria 61.0 288 41 40 44 33 1 20. Hiszpania 57.5 238 31 34 46 43 1 21. Węgry 53.0 244 35 37 30 27 3 22. Nowa Zelandia 42.5 207 27 35 29 25 2 23. Brazylia 42.0 174 27 20 26 25 4 24. Finlandia 42.0 172 23 23 34 33 1 25. Białoruś 36.0 187 24 31 29 22 26. -

BA Ritgerð the Change of Tides

BA ritgerð Japanskt Mál og menning The Change of tides: The advent of non-nationals in Sumo Henry Fannar Clemmensen Leiðbeinandi Gunnella Þorgeirsdóttir September 2019 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Japanskt mál og menning The Change of Tides: The advent of non-nationals in Sumo Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs Henry Fannar Clemmensen Kt.: 260294-3429 Leiðbeinandi: Gunnella Þorgeirsdóttir September 2019 1 Abstract Non-Japanese sumo wrestlers are common today, but that has not always been the case. For over a thousand years sumo tournaments were exclusively held by Japanese men, and up until the 1960s foreigners were almost unheard of in the professional sumo scene. As the world’s modernization and internationalization accelerated so did foreign interest in the National sport of sumo. Today the sport has spread to over 87 countries which have joined the International Sumo Federation. With an interest in professional sumo in Japan at an all-time low and with fewer wrestlers applying to stables than ever before, viewers of tournaments and media coverage of events has been decreasing, which is closely followed by western originated sports having overtaken sumo in popularity e.g. soccer and baseball. Yet the interest in sumo on an international scale has increased considerably. In which way has this rising internationalization affected the sumo world and the professional sumo world and how is it reflected in modern Japanese society, in what way did the wrestlers coming from overseas experience the sumo culture compared to how it is today? Today the sumo scene is largely dominated by Mongolian wrestlers, how did this come to pass and how has the society of Japan reacted to these changes. -

Today's Sumo Wrestlers Lack Spirit — Possibility of the Advent Of

CULTURE Today’s Sumo Wrestlers Lack Spirit — Possibility of the advent of Japanese yokozuna Interview with Hakkaku Nobuyoshi, Chairman of Nihon Sumo Kyokai and former sumo wrestler Hokutoumi by Nagayama Satoshi, ex-journalist for Yomiuri Ozumo Whether you are Japanese or Mongolian does not matter in sumo Nagayama Satoshi: You were reappointed as the chairman of Nihon Sumo Kyokai in March. Around six months have passed since your initial appointment on December 18 last year. How do you feel now? Hakkaku Nobuyoshi : I have settled into the position. The outside directors helped me a lot, and I have undertaken my job by trial and error. As a result, I’m gradually becoming more confident. I have had a hectic time since Kitanoumi, the previous chairman, passed away. I have refrained from drinking for a year. Very recently, I have played the occasional round of golf. The Grand Sumo Tournament is very popular, with every date fully booked. Sumo fans still want a Japanese yokozuna. Personally, I believe that someone is a sumo wrestler as soon as he starts his career, whether he is Japanese or Mongolian. In reality, many sumo fans often tell me that they want a Japanese yokozuna. What do you want young Japanese sumo wrestlers to do to become a yokozuma? Hakkaku Nobuyoshi, Chairman of Nihon Sumo Kyokai and former sumo wrestler Hokutoumi I think that many of them have already given up any © CHUO KORON SHINSHA 2016 hope of beating Hakuho or being as strong as him. In a way, they don’t even have a dream. -

Saiki City: Sumo Wrestler

Saiki city: Sumo Wrestler Saiki City is our Sister City in Japan! This means we share a very special friendship with the city and have lots in common. Similar to Gladstone, Saiki City loves its sport! There is a famous sumo wrestler from Saiki City called Yoshikaze Masatsugu. Yoshikaze achieved the third highest sumo wrestler rank, sekiwake, in January 2016. He has won many challenges against strong opponents including those with the highest sumo wrestler ranking, yokozuna. Make Your Own Sumo • Take one piece of pink paper – this is the body and head of the sumo • Thread one pipe cleaner through the holes at the top and fold to make arms • Thread another pipe cleaner through the holes at the bottom and fold to make legs • Glue the white cardboard sumo to the back of the pink piece, covering the pipe cleaners • Fold a white tissue in half to create a triangle • Glue all three corners to the middle of the pink sumo, creating the Mawashi Hiroshima: Origami Origami is the ancient Japanese tradition of folding paper to create new shapes. Hiroshima is the centre for peace in Japan. Every year, thousands of people travel to Hiroshima to leave origami paper cranes at the Hiroshima Children’s Peace Monument. There is a legend that says if you can make one thousand paper cranes you will be granted a wish. Make your own crane (ADVANCED) Make your own dog (BEGINNER) Osaka: sushi Osaka was once the centre for rice trade during the Edo period (between 1603 and 1868). Today, Osaka is known as Tenka no Daidokoro – the nation’s kitchen. -

List of Sports

List of sports The following is a list of sports/games, divided by cat- egory. There are many more sports to be added. This system has a disadvantage because some sports may fit in more than one category. According to the World Sports Encyclopedia (2003) there are 8,000 indigenous sports and sporting games.[1] 1 Physical sports 1.1 Air sports Wingsuit flying • Parachuting • Banzai skydiving • BASE jumping • Skydiving Lima Lima aerobatics team performing over Louisville. • Skysurfing Main article: Air sports • Wingsuit flying • Paragliding • Aerobatics • Powered paragliding • Air racing • Paramotoring • Ballooning • Ultralight aviation • Cluster ballooning • Hopper ballooning 1.2 Archery Main article: Archery • Gliding • Marching band • Field archery • Hang gliding • Flight archery • Powered hang glider • Gungdo • Human powered aircraft • Indoor archery • Model aircraft • Kyūdō 1 2 1 PHYSICAL SPORTS • Sipa • Throwball • Volleyball • Beach volleyball • Water Volleyball • Paralympic volleyball • Wallyball • Tennis Members of the Gotemba Kyūdō Association demonstrate Kyūdō. 1.4 Basketball family • Popinjay • Target archery 1.3 Ball over net games An international match of Volleyball. Basketball player Dwight Howard making a slam dunk at 2008 • Ball badminton Summer Olympic Games • Biribol • Basketball • Goalroball • Beach basketball • Bossaball • Deaf basketball • Fistball • 3x3 • Footbag net • Streetball • • Football tennis Water basketball • Wheelchair basketball • Footvolley • Korfball • Hooverball • Netball • Peteca • Fastnet • Pickleball -

Le Petit Banzuke Illustré Le Guide Pratique Pour Bien Suivre Le Basho Supplément Du Magazine Le Monde Du Sumo

Le Petit Banzuke Illustré Le guide pratique pour bien suivre le basho Supplément du magazine Le Monde du Sumo HARU basho 2008 Sakaizawa (Maegashira 15) 9 – 23 mars Jijipress Takekaze (Komusubi) Jijipress Sponichi Hokutokuni (Juryo 12) Tosayutaka (Juryo 12) Le banzuke complet du Haru basho 2008 Un gros plan sur les lutteurs classés en makuuchi et juryo Et aussi : • Un récapitulatif des 6 derniers tournois des lutteurs de makuuchi • Les débuts de la promotion Hatsu 2008 • Les changements de shikona et intai Hochi フランス語の大相撲雑誌 Hors série n°26 – mars 2008 Editorial faute de promotion au rang supérieur, d’affilée sans blessure. Une première pour l’ordre des ozeki s’établit suivant leur lui en un an et demi. Il n’était pourtant pas Hochi Hochi dernière performance, le meilleur prenant au mieux de sa forme au Hatsu basho, (ou gardant) la place côté est. comme en témoigne son résultat, et cela Dans le cas présent, c’est plutôt le pourrait réserver de mauvaises surprises… moins décevant, Kotooshu, qui est passé en Iwakiyama a du mal à se remettre de tête, grâce à un score de 9-6 en janvier. Juste son passage en division juryo l’année passée, derrière, avec leur bien faible 8-7, suivent et c’est lentement qu’il tente à présent de Kaio et Kotomitsuki. remonter dans le classement. Chiyotaikai ferme la marche, et son Beaucoup plus loin dans le banzuke, forfait après 7 défaites consécutives au à seulement quelques rangs de la division Hatsu basho ne va pas lui faciliter la tâche ; juryo, le jeune espoir Ichihara a légèrement il sera en effet kadoban, pour la 11ème fois de déçu au dernier tournoi. -

Japanese Folk Tale

The Yanagita Kunio Guide to the Japanese Folk Tale Copublished with Asian Folklore Studies YANAGITA KUNIO (1875 -1962) The Yanagita Kunio Guide to the Japanese Folk Tale Translated and Edited by FANNY HAGIN MAYER INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS Bloomington This volume is a translation of Nihon mukashibanashi meii, compiled under the supervision of Yanagita Kunio and edited by Nihon Hoso Kyokai. Tokyo: Nihon Hoso Shuppan Kyokai, 1948. This book has been produced from camera-ready copy provided by ASIAN FOLKLORE STUDIES, Nanzan University, Nagoya, japan. © All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses' Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Nihon mukashibanashi meii. English. The Yanagita Kunio guide to the japanese folk tale. "Translation of Nihon mukashibanashi meii, compiled under the supervision of Yanagita Kunio and edited by Nihon Hoso Kyokai." T.p. verso. "This book has been produced from camera-ready copy provided by Asian Folklore Studies, Nanzan University, Nagoya,japan."-T.p. verso. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Tales-japan-History and criticism. I. Yanagita, Kunio, 1875-1962. II. Mayer, Fanny Hagin, 1899- III. Nihon Hoso Kyokai. IV. Title. GR340.N52213 1986 398.2'0952 85-45291 ISBN 0-253-36812-X 2 3 4 5 90 89 88 87 86 Contents Preface vii Translator's Notes xiv Acknowledgements xvii About Folk Tales by Yanagita Kunio xix PART ONE Folk Tales in Complete Form Chapter 1. -

Masterpieces of Japanese Art Cincinnati Art Museum February 14 – August 30, 2015 Docent Packet

Masterpieces of Japanese Art Cincinnati Art Museum February 14 – August 30, 2015 Docent Packet The Masterpieces of Japanese Art exhibit celebrates the beauty and breadth of the Cincinnati Art Museum’s permanent collection. The one hundred featured artworks exemplify five centuries of artistic creation. They were selected from over three thousand Japanese objects, including paintings, screens, ceramics, lacquer and metal wares, ivory carvings, arms and armor, dolls, masks, cloisonné, textiles and costumes. The Cincinnati Art Museum was one of the first museums in the United States to collect Japanese art, thanks to many generous patrons, including business people and artists, who traveled to Japan. From the Director’s Forward to the catalog: “We will forever be grateful to Dr. Hou-mei Sung for assembling Masterpieces of Japanese Art and for spearheading an extensive project of researching, cataloging, documenting, and preserving these works. Without her scholarship, her vision and her passion for Japanese art we would not be in a position to share this collection in such a complete and thorough fashion.” Aaron Betsky The packet begins with a short history of Japanese art history and a discussion of Heian Court Life which influenced many artworks in the exhibit. Five sections are organized around themes that could be used to plan a tour or to select artworks across the themes to customize a tour. The Animals and Fashion tours are family friendly. The Asian Painting, Religion and Donors tours appeal to a wide audience. The committee is very grateful to Dr. Sung for selecting the highlights of the exhibit that are featured in this docent packet. -

2011 Calendar UBC Cities Events Calendar 2011 Dear UBC Friends

2011 UBC Cities Events 2011 Calendar UBC Cities Events Calendar Dear UBC Friends, All UBC cities offer a variety of things to see and do. The numerous events all year long and thousands of people make the city’s atmosphere vibrant and lively. The new edition of the UBC Cities Events Calendar 2011 will help you to choose from a wide range of options and to plan the travels. The Calendar gathers the event information in one publication being a useful informative guide to business, cultural, sporting, recreational activities and exhibitions organized in your cities. This publication presents the highlights of the events held around the Baltic Sea and does not make a claim to be complete. You are welcome to contact the municipalities and tourist information centers for further information. Let’s meet in the UBC cities! With the Baltic Sea greetings, Per Bødker Andersen President of UBC DENMARK GERMANY 86 - 87 Gdańsk 88 - 89 Gdynia 2 Aalborg 46 - 47 Greifswald 90 - 91 Koszalin 3 - 4 Århus 48 - 49 Kiel 92 Łeba 5 - 6 Kolding 50 - 51 52 Lübeck 93 Malbork 7 Næstved - 53 Rostock 94 - 95 Międzyzdroje 54 - 55 Wismar 96 - 97 Pruszcz Gd. ESTONIA 98 - 99 Słupsk LATVIA 100 Sopot 8 Elva 101 - 102 Szczecin 9 Jõgeva 56 - 57 Cēsis 103 Ustka 10 Jõhvi 57 Tukums 11 Kärdla 58 - 59 Jēkabpils RUSSIA 12 - 13 Kuressaare 60 - 61 Jūrmala 14 - 15 Narva 62 - 63 Liepāja 104 Baltijsk 16 - 17 Pärnu 64 - 65 Riga 105 - 106 Kaliningrad 18 Rakvere 19 - 20 Tallinn LITHUANIA SWEDEN 21 - 22 Tartu 23 Viljandi 66 - 67 Gargždai 107 Botkyrka 24 - 25 Võru 68 - 69 Kaunas 108 Halmstad