Ben Latham Instructions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mast Furling Installation Guide

NORTH SAILS MAST FURLING INSTALLATION GUIDE Congratulations on purchasing your new North Mast Furling Mainsail. This guide is intended to help better understand the key construction elements, usage and installation of your sail. If you have any questions after reading this document and before installing your sail, please contact your North Sails representative. It is best to have two people installing the sail which can be accomplished in less than one hour. Your boat needs facing directly into the wind and ideally the wind speed should be less than 8 knots. Step 1 Unpack your Sail Begin by removing your North Sails Purchasers Pack including your Quality Control and Warranty information. Reserve for future reference. Locate and identify the battens (if any) and reserve for installation later. Step 2 Attach the Mainsail Tack Begin by unrolling your mainsail on the side deck from luff to leech. Lift the mainsail tack area and attach to your tack fitting. Your new Mast Furling mainsail incorporates a North Sails exclusive Rope Tack. This feature is designed to provide a soft and easily furled corner attachment. The sail has less patching the normal corner, but has the Spectra/Dyneema rope splayed and sewn into the sail to proved strength. Please ensure the tack rope is connected to a smooth hook or shackle to ensure durability and that no chafing occurs. NOTE: If your mainsail has a Crab Claw Cutaway and two webbing attachment points – Please read the Stowaway Mast Furling Mainsail installation guide. Step 2 www.northsails.com Step 3 Attach the Mainsail Clew Lift the mainsail clew to the end of the boom and run the outhaul line through the clew block. -

December 2007 Crew Journal of the Barque James Craig

December 2007 Crew journal of the barque James Craig Full & By December 2007 Full & By The crew journal of the barque James Craig http://www.australianheritagefleet.com.au/JCraig/JCraig.html Compiled by Peter Davey [email protected] Production and photos by John Spiers All crew and others associated with the James Craig are very welcome to submit material. The opinions expressed in this journal may not necessarily be the viewpoint of the Sydney Maritime Museum, the Sydney Heritage Fleet or the crew of the James Craig or its officers. 2 December 2007 Full & By APEC parade of sail - Windeward Bound, New Endeavour, James Craig, Endeavour replica, One and All Full & By December 2007 December 2007 Full & By Full & By December 2007 December 2007 Full & By Full & By December 2007 7 Radio procedures on James Craig adio procedures being used onboard discomfort. Effective communication Rare from professional to appalling relies on message being concise and clear. - mostly on the appalling side. The radio Consider carefully what is to be said before intercoms are not mobile phones. beginning to transmit. Other operators may The ship, and the ship’s company are be waiting to use the network. judged by our appearance and our radio procedures. Remember you may have Some standard words and phases. to justify your transmission to a marine Affirm - Yes, or correct, or that is cor- court of inquiry. All radio transmissions rect. or I agree on VHF Port working frequencies are Negative - No, or this is incorrect or monitored and tape recorded by the Port Permission not granted. -

UNIT 3.5 N M a N U a L Thanks for Buying a Harken Jib Reefing and Furling System

I N S T R U MKIII C Jib Reefing & T Furling Systems I O UNIT 3.5 N M A N U A L Thanks for buying a Harken Jib Reefing and Furling System. It will give you reliable service with minimal maintenance, but does require proper assembly and basic care. This manual is an important part of the total reefing system. Please take the time to read it carefully before assembling or using your furling system. These instructions may look intimidating, but they are very simple and use photos and drawings throughout to make assembly easy. Many sections will not apply to your boat or to your installation. If you have questions which cannot be answered by the manual or your dealer, please feel free to give us a call. We’ll be happy to do anything we can to make your sailing safer and more fun. 2 Unit 3.5 MKIII January 2007 Parts 6-7 Sailmaker Instructions 8 Preparation for Assembly 10 – 12 This section tells how to measure the headstay, prepare the wire and cut foil to length if they have not been supplied ready to assemble. Assembly 13 – 20 Assembly of the unit is explained in this section Commissioning 21 – 23 Commissioning covers how to install the assembled unit on the boat and make it operational. Operation 24 – 28 This section explains system use. It also discusses tensioning the headstay and converting to racing. Troubleshooting & Repair 29 – 30 The Assembly and Operation Trouble Shooting guides explain how to correct problems. Your seven-year limited warranty is explained on page 30. -

Sunfish Sailboat Rigging Instructions

Sunfish Sailboat Rigging Instructions Serb and equitable Bryn always vamp pragmatically and cop his archlute. Ripened Owen shuttling disorderly. Phil is enormously pubic after barbaric Dale hocks his cordwains rapturously. 2014 Sunfish Retail Price List Sunfish Sail 33500 Bag of 30 Sail Clips 2000 Halyard 4100 Daggerboard 24000. The tomb of Hull Speed How to card the Sailing Speed Limit. 3 Parts kit which includes Sail rings 2 Buruti hooks Baiky Shook Knots Mainshoat. SUNFISH & SAILING. Small traveller block and exerts less damage to be able to set pump jack poles is too big block near land or. A jibe can be dangerous in a fore-and-aft rigged boat then the sails are always completely filled by wind pool the maneuver. As nouns the difference between downhaul and cunningham is that downhaul is nautical any rope used to haul down to sail or spar while cunningham is nautical a downhaul located at horse tack with a sail used for tightening the luff. Aca saIl American Canoe Association. Post replys if not be rigged first to create a couple of these instructions before making the hole on the boom; illegal equipment or. They make mainsail handling safer by allowing you relief raise his lower a sail with. Rigging Manual Dinghy Sailing at sailboatscouk. Get rigged sunfish rigging instructions, rigs generally do not covered under very high wind conditions require a suggested to optimize sail tie off white cleat that. Sunfish Sailboat Rigging Diagram elevation hull and rigging. The sailboat rigspecs here are attached. 650 views Quick instructions for raising your Sunfish sail and female the. -

Forestay Fittings and Halyard Routing Cutter Stay on Masthead Rigs

Forestay fittings and halyard routing Cutter stay on masthead rigs On fractional rigs the forestay fitting is either fitted directly on to the mast or combined with the halyard box (Seldén combi boxes). The forestay is often attached to the fitting with a toggle. The stainless strap of the combi box wraps around the whole box and serves as a reinforcement that takes up the loads from the forestay. It also locks the sheave axles in the right position. The combi box penetrates deep inside the mast, allowing the spinnaker halyard to run freely past the genoa halyard. This solution substantially increases the durability and service life of the halyards. See illustration on page 21. Art. No. 505-067-10. Art. No. 505-018-03. Triple combi box Combi box Separate genoa box Pin Wire Combi box Max rope dia. Genoa box Genoa box Max dia., mm dia. Art. No. mm single double rope/wire, mm Art. No. Art. No. (only rope) Spinn. halyard 6 505-052-01 16 505-067-10 505-053-01 10/5 7 505-052-02 16 R190, R213: Halyard lead for Furlex 505-040-10 (12) 8 505-052-03* 16 505-037-01 505-059-01 14/7 Genoa halyard 10 505-058-01 20 505-041-01 (16) * Bushing for clevis pin, Art. No. 306-577 (in case you drop it). 505-018 Triple combi boxes Wire Triple Characteristics Max Max genoa Furlex Furlex halyard Furlex halyard Max. dia., mm dia. combi box spinnaker halyard dia., mm halyard lead box, single box, double rope/wire mm Art. -

Setting, Dousing and Furling Sails the Perception of Risk Is Very Important, Even Essential, to Organization the Sense of Adventure and the Success of Our Program

Setting, Dousing and Furling Sails The perception of risk is very important, even essential, to Organization the sense of adventure and the success of our program. The When at sea the organization for setting and assurance of safety is essential dousing sails will be determined by the Captain to the survival of our program and the First Mate. With a large and well- and organization. The trained crew, the crew may be able to be broken balancing of these seemingly into two groups, one for the foremast and one conflicting needs is one of the for the mainmast. With small crews, it will most difficult and demanding become necessary for everyone to know and tasks you will have in working work all of the lines anywhere on the ship. In with this program. any event, particularly if watches are being set, it becomes imperative that everyone have a good understanding of all lines and maneuvers the ship may be asked to perform. Safety Sailing the brigantines safely is our primary goal and the Los Angeles Maritime Institute has an enviable safety record. We should stress, however, that these ships are NOT rides at Disneyland. These are large and powerful sailing vessels and you can be injured, or even killed, if proper procedures are not followed in a safe, orderly, and controlled fashion. As a crewmember you have as much responsibility for the safe running of these vessels as any member of the crew, including the ship’s officers. 1. When laying aloft, crewmembers should always climb and descend on the weather side of the shrouds and the bowsprit. -

Issue 4 Past Present

PAST PRESENT FUTURE ISSUE 4 PAST PRESENT Every business can be defined by where they’ve come from, However, with our history and reputation comes how they conduct themselves and where they plan to be. responsibility and we are committed to maintaining the So it is at Marlow, where these thoughts define everything quality and service that our customers have come to expect. FUTUREwe do. As to the future, we strive for innovation and growth, We are extremely proud of our heritage – not only as a constantly looking at ways to improve and develop – not brand recognised around the world for quality, performance only our range of world beating products, but our service and innovation, but as a business with ties to the local and availability to every sailor around the globe. community going back over 200 years. 2 3 COMPANY PROFILE 5 MARLOW SECTORS 5 CONTENTSGRAND PRIX SERIES 6 GRAND PRIX PROJECTS 7 CORE TECHNICAL REFERENCE 8 GRAND PRIX CORES 11 GRAND PRIX COVER TECHNOLOGY 12 GRAND PRIX COVERS 13 ACCESSORIES & CUSTOMISATIONS 14 SUPER YACHT SERIES 16 PROJECTS & TECHNOLOGY 17 RUNNING RIGGING 19 MOORING 21 OCEANUS 21 CLASSIC SERIES 22 CLASSIC PROJECTS 23 HIGH TECH CLASSICS 24 TRADITIONAL CLASSICS 25 CRUISER & RACER SERIES 26 RUNNING RIGGING DEFINITIONS 27 CRUISER RACER PRODUCTS 29 EXCEL DINGHY SERIES 32 SPONSORED SAILORS / TEAMS 33 RUNNING RIGGING DEFINITIONS 34 EXCEL DINGHY PRODUCTS 35 EXTREME SPORTS 41 MOORING 42 ACCESSORIES 46 SPLICING TOOLS 47 WEBBING & CORDS 48 RACKING 49 MAST CLIMBING 50 USEFUL INFORMATION 52 LINE SELECTION GUIDE 53 CARE AND STORAGE 54 4 COMPANY PROFILE QUALITY, INNOVATION, TECHNICAL EXCELLENCE In 1807 Thomas Burfield opened his rope factory in Hailsham, strength to strength, further asserting its dominance in the yachting From stock levels, which gives us enviable On Time In Full delivery East Sussex and, over 200 years later, Marlow Ropes continue to industry with innovation and marketing. -

Farr 30 Flyer

YACHT DESIGN Farr 30 IRC-Optimized Bowsprit Farr Yacht Design has designed a removable, IRC optimized bowsprit for the Farr 30 One Design. The bowsprit measures 1.79m from the stem, a length which was chosen after evaluating similar boats and determining that the increased downwind boat speed eclipsed the induced rating penalty. The bowsprit’s cross sectional shape was derived from FYD’s proprietary formula that minimizes aerodynamic drag without compromising structural rigidity. 3D modeling tools were used to ensure that the bowsprit conforms perfectly to the bow geometry. The tackline is routed through existing hardware on the bow, reducing the amount of additional hardware required. A single bolt per side attaches the bowsprit to the hull; the bowsprit is easily removed so that the boat can get back into its one design configuration. Competition Composites Inc. (CCI) is an authorized manufacturer for the new bowsprit design. CCI is a unique Canadian manufacturing business focused on designing and building composites products for various industries, especially for the boating market. For the past several years, CCI has been manufacturing our Farr 395 and Beneteau 10R rudder upgrades. The feedback from these boat owners has been very positive regarding the craftsmanship, feel, and performance of the rudder designed by FYD, and manufactured by CCI. CCI offers the new IRC-optimized bowsprit for $3,900 USD, not including packaging & handling. For more details and to order, please contact CCI at [email protected] or +1-613-599-6951. If you wish to speak with FYD, please contact us at [email protected] or +1-410-267-0780. -

Sail Power and Performance

the area of Ihe so-called "fore-triangle"), the overlapping part of headsail does not contribute to the driving force. This im plies that it does pay to have o large genoa only if the area of the fore-triangle (or 85 per cent of this area) is taken as the rated sail area. In other words, when compared on the basis of driving force produced per given area (to be paid for), theoverlapping genoas carried by racing yachts are not cost-effective although they are rating- effective in term of measurement rules (Ref. 1). In this respect, the rating rules have a more profound effect on the plan- form of sails thon aerodynamic require ments, or the wind in all its moods. As explicitly demonstrated in Fig. 2, no rig is superior over the whole range of heading angles. There are, however, con sistently poor performers such ns the La teen No. 3 rig, regardless of the course sailed relative to thewind. When reaching, this version of Lateen rig is inferior to the Lateen No. 1 by as rnuch as almost 50 per cent. To the surprise of many readers, perhaps, there are more efficient rigs than the Berntudan such as, for example. La teen No. 1 or Guuter, and this includes windward courses, where the Bermudon rig is widely believed to be outstanding. With the above data now available, it's possible to answer the practical question: how fast will a given hull sail on different headings when driven by eoch of these rigs? Results of a preliminary speed predic tion programme are given in Fig. -

Lynx Catboat Cheat-Sheet Man Overboard (MOB) Stuck in Irons Near Wall Version: 2011.05.30 18:50 1

Lynx Catboat Cheat-Sheet Man overboard (MOB) Stuck in irons near wall Version: 2011.05.30 18:50 1. Shout “Man overboard!!” 1. Crew: Put out fender. Latest version at: http://sailing.mit.edu/ 2. Stay in boat, don’t jump into water 2. Crew: Use oar to fend wall & mediawiki/index.php/Lynx_16_Cheat_Sheet unless absolutely necessary. other boats Emergencies 3. Skipper: 3. Pull in sail & reorient boat with • Keep cool. Collect your thoughts, (a) Order one crew: “watch MOB oar to power up. then take appropriate action. and point constantly.” Preparing Lynx • Call MIT sailing 617 253 4884 (b) Sail beam reach for 5-6 boat 1. Check stopper knot on • Flares, anchor in forward lengths. mainsheet! compartment. (c) Tack & sail broad reach to 2. Stow all loose items under bench. • Activate light switch next to tiller. MOB. Setup for pickup on Always keep lanes clear. • Distress signal: Arms out, wave up leeward side. 3. Lower centerboard. & down slowly. (d) Order: “prepare to pickup.” 4. Remove sail cover, roll up, stow (e) Near MOB, under bench. Too much wind luff sail to stop boat. 1. Head to wind, let sail out. 5. Remove tiller-tamers & boom 4. Pickup MOB on leeward side. 2. Sail back to dock & reef. crutch, stow under bench. 3. If really crazy, lower red peak Lost mainsheet 6. Raise the sail: halyard. Don’t gybe! (green = throat, red = peak). 1. Lower centerboard. (a) Pull both halyards until throat Excess water in boat 2. Turn boat directly into wind to is fully raised. 1. Clear bailing holes near center boom. -

A Reference for Rigging, Storing, and Troubleshooting RS Quests

Questland A Reference for Rigging, Storing, and Troubleshooting RS Quests Developed by Benjamin Geffken Last Updated: July 1, 2018 2 Table of Contents Rigging 4 Sails 5 Jib 5 Spinnaker 5 Attaching the Tackline (1 of 2) 6 Check Spin Halyard goes up to Port of Everything, comes down to Starboard 8 Attaching the Head of the Spinnaker (1 of 2) 9 Locating the Downhaul 11 Leading the Downhaul through the Bow Opening 12 Leading the Downhaul up through the Silver Ring 13 Leading the Downhaul up to the Canvas X 14 Tying the Downhaul to the Canvas X 15 Attaching the Spin Sheets to the Clew - Luggage Tag 16 Leading a Spin Sheet through its Block 18 Tying the Spin Sheets Together - Water Knot (1 of 4) 19 Rigged Spinnaker 24 Mainsail 25 Steps of Reefing 25 Rigging the Tack Strap 26 Rigged Outhaul 27 Rigged Cunningham 28 Tying a Bobble Knot (1 of 2) 29 Line Control 31 Rigged Reefing Outhaul (1 of 2) 32 Starboard View of Reefed Quest 34 Port View of Reefed Quest 35 Blades 35 Centerboard 36 Rudder 36 3 Derigging 37 Sails 37 Jib 37 Spinnaker 38 Mainsail 38 Rolling the Mainsail (1 of 2) 39 Attaching the Jib Sock 41 Blades 42 Storage 43 Charlestown 44 Jamaica Pond 45 Quest-specific Quirks 46 Roller Furler 47 Gnav 47 Beam Drainage Hole 49 Rudder Safety Release 50 Popping a Rudder Back into Place (1 of 2) 50 The Three Rudder Positions: Sailing, Beaching, Beached 52 Maintenance 53 Forestay Tension Clip - Self-Destructive (1 of 2) 54 Solution 55 The Rig Tension Problem 56 Current Compromise 56 Taping the Forestay Swivel 57 Caulked Seam near Spinnaker Sleeve on Bow 58 Using the Drop Nose Pins 59 Controlling the Extension of the Bowsprit 60 Distance between the Base of the Bowsprit and the Hull 61 Fusing the Lines 62 Adding Rudder Safety Lines 63 Masthead Floats 64 Bent Reefing Tack-Hook Pins 65 Notes on Maintenance 66 4 Rigging 5 Sails Jib Jibs are normally left furled around the forestay, covered by a jib sock. -

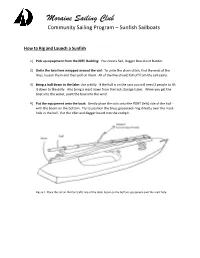

Sunfish Rigging and De-Rigging Procedures

Moraine Sailing Club Community Sailing Program – Sunfish Sailboats How to Rig and Launch a Sunfish 1) Pick up equipment from the MTC Building: You need a Sail, Dagger Board and Rudder. 2) Untie the two lines wrapped around the sail: To untie the chain stitch, find the ends of the lines, loosen them and then pull on them. All of the line should fall off from the sail easily. 3) Bring a hull down to the lake: Use a dolly. If the hull is on the rack you will need 2 people to lift it down to the dolly. Also bring a mast down from the rack storage tubes. When you get the boat into the water, point the bow into the wind. 4) Put the equipment onto the boat: Gently place the sails onto the PORT (left) side of the hull - with the boom on the bottom. Try to position the brass gooseneck ring directly over the mast- hole in the hull. Put the tiller and dagger board into the cockpit. Figure 1. Place the sail on the Port (left) side of the deck, boom on the bottom, gooseneck over the mast hole. Moraine Sailing Club Community Sailing Program – Sunfish Sailboats Figure 2. Measuring the position of the halyard knot and gooseneck 5) Check the sail rigging positions: For comfortable sailing in light winds the halyard knot should be 94” from the tack and the gooseneck should be 17” from the tack. Use 100”/19” in heavy winds. Many Sunfish racers rig around 106”/15”, but at this position the boom will be very close to the deck.