Working Paper No. 81 Rakesh Chaubey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supreme Court of India Bobby Art International, Etc Vs Om Pal Singh Hoon & Ors on 1 May, 1996 Author: Bharucha Bench: Cji, S.P

Supreme Court of India Bobby Art International, Etc vs Om Pal Singh Hoon & Ors on 1 May, 1996 Author: Bharucha Bench: Cji, S.P. Bharucha, B.N. Kirpal PETITIONER: BOBBY ART INTERNATIONAL, ETC. Vs. RESPONDENT: OM PAL SINGH HOON & ORS. DATE OF JUDGMENT: 01/05/1996 BENCH: CJI, S.P. BHARUCHA , B.N. KIRPAL ACT: HEADNOTE: JUDGMENT: WITH CIVIL APPEAL NOS. 7523, 7525-27 AND 7524 (Arising out of SLP(Civil) No. 8211/96, SLP(Civil) No. 10519-21/96 (CC No. 1828-1830/96 & SLP(C) No. 9363/96) J U D G M E N T BHARUCHA, J. Special leave granted. These appeals impugn the judgment and order of a Division Bench of the High Court of Delhi in Letters Patent appeals. The Letters Patent appeals challenged the judgment and order of a learned single judge allowing a writ petition. The Letters Patent appeals were dismissed, subject to a direction to the Union of India (the second respondent). The writ petition was filed by the first respondent to quash the certificate of exhibition awarded to the film "Bandit Queen" and to restrain its exhibition in India. The film deals with the life of Phoolan Devi. It is based upon a true story. Still a child, Phoolan Devi was married off to a man old enough to be her father. She was beaten and raped by him. She was tormented by the boys of the village; and beaten by them when she foiled the advances of one of them. A village panchayat called after the incident blamed Phoolan Devi for attempting to entice the boy, who belonged to a higher caste. -

“Low” Caste Women in India

Open Cultural Studies 2018; 2: 735-745 Research Article Jyoti Atwal* Embodiment of Untouchability: Cinematic Representations of the “Low” Caste Women in India https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2018-0066 Received May 3, 2018; accepted December 7, 2018 Abstract: Ironically, feudal relations and embedded caste based gender exploitation remained intact in a free and democratic India in the post-1947 period. I argue that subaltern is not a static category in India. This article takes up three different kinds of genre/representations of “low” caste women in Indian cinema to underline the significance of evolving new methodologies to understand Black (“low” caste) feminism in India. In terms of national significance, Acchyut Kanya represents the ambitious liberal reformist State that saw its culmination in the constitution of India where inclusion and equality were promised to all. The movie Ankur represents the failure of the state to live up to the postcolonial promise of equality and development for all. The third movie, Bandit Queen represents feminine anger of the violated body of a “low” caste woman in rural India. From a dacoit, Phoolan transforms into a constitutionalist to speak about social justice. This indicates faith in Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s India and in the struggle for legal rights rather than armed insurrection. The main challenge of writing “low” caste women’s histories is that in the Indian feminist circles, the discourse slides into salvaging the pain rather than exploring and studying anger. Keywords: Indian cinema, “low” caste feminism, Bandit Queen, Black feminism By the late nineteenth century due to certain legal and socio-religious reforms,1 space of the Indian family had been opened to public scrutiny. -

The Hunt for Phoolan Devi

• COVER STORY THE HUNT FOR \ • .\-~ !PHOOLAN '--------I OEVI On theafternoonof31 March, when on an informer'a' rrp-Off the police surrounded Gulauli village in UP)j' Jalaun district, they thought they would finally, get the dacoit queen Phoolan Devi; but she slipped awa;}!. Nirmal Mitra visited Gulauli to report on the massive hunt, and the ~~~ .. encounte~ j.n.which most of Phoolan's gang was wiped out. ~ hoolan Devi. the dacoit PhoOian Devi had been arrested and queen. is a desperate was being brought 10 UP's capital by ~ ~\ woman loday, fun ninA for helicopter; it was later discovered to her life. The whole police be an A.pril Fool's joke. Even the news force of Unar Pradesh agencies had been taken in by this se~msP to be after her; she is every.- prank.) one's prize catcli. More than half of The manner in which Phoolan Devi her small gang has already been wiped escaped from the police on 31 March out in one encounter with the police makes an ahsolutely fascinating story. after another during this war that the typical of all that has come to be police have launched on dacoits after associated with dacoits-violence. wit. the bloody revenge that Phoolan Devi presence of mind, and that important took on the Behmai rhaJcurs (see Sun- mgredient, a sense of honour. It seems day 15 March) who had once insulted straight tiut of a Bombay film. and humiliated her. Other important Raba Mustaqim (he was a Muslim) dacoit leaders are angry':with her; by was killed on 4 March near Akbarpur this one outrage. -

La Regina Dei Banditi.Rtf

EDIZIONE SPECIALE In occasione del IV° Festival Internazionale della Letteratura Resistente Pitigliano - Elmo di Sorano, 8 - 9 - 10 settembre 2006 La Regina dei banditi uno spettacolo di Mutamenti Compagnia Laboratorio MILLELIRE STAMPA ALTERNATIVA con Sara Donzelli Direzione editoriale Marcello Baraghini regia Giorgio Zorcù drammaturgia Federico Bertozzi produzione Accademia Amiata Mutamenti Accademia Amiata Mutamenti Toscana delle Culture 58031 Arcidosso (Gr) tel. 348 4036571 [email protected] Grafica di copertina C&P Adver 3 Le pareti della casa erano spalmate di fango, il tet- to era di paglia. All’interno tre stanze affacciate su un cortiletto. Una per dormire, una per cucinare e una per le mucche. Nessuna finestra, vivevano al buio. Di rado, una scatola di latta con lo stoppino diventava una lampada; olio non ce n’era: costava troppo. A parte tre stuoie nella stanza della notte e una sulla soglia di quella delle mucche, l’unico arre- damento della casa era un tempietto votivo. Nella stagione calda dormivano all’aperto. Le mucche dormivano sempre al chiuso per paura dei ladri. E- rano poveri mallah: possedevano solo i regali del fiume. Alla piccola Phoolan piaceva l’odore della terra bagnata. Ne raccoglieva manciate e le masticava: era un sapore inebriante. Di manghi e lenticchie ne mangiavano pochi. Di giorno, durante il lavoro nei 5 campi, si nutrivano con piselli salati, di sera solo pa- tate. Mentre la veglia si alternava al sonno e il lavo- ro al poco riposo, la fame era continua. Come il re- spiro. Un giorno Phoolan fu convocata dal Pradham, uomo importante, capo di tutti i villaggi del distret- to, perché gli togliesse i pidocchi. -

Adivasi Insurrections in India: the 1857 Rebellion in Central India, Its Wider Context and Historiography

Edinburgh Research Explorer Adivasi Insurrections in India: the 1857 Rebellion in central India, its wider context and historiography Citation for published version: Bates, C 2008, 'Adivasi Insurrections in India: the 1857 Rebellion in central India, its wider context and historiography', Paper presented at Savage Attack: adivasi insurrection in South Asia, Royal Asiatic Society, London, United Kingdom, 30/06/09 - 1/07/09. Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Early version, also known as pre-print Publisher Rights Statement: © Bates, C. (2008). Adivasi Insurrections in India: the 1857 Rebellion in central India, its wider context and historiography. Paper presented at Savage Attack: adivasi insurrection in South Asia, Royal Asiatic Society, London, United Kingdom. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 Adivasi Insurrections in India: the 1857 Rebellion in central India, its wider context and historiography (draft only – do not quote) Crispin Bates University of Edinburgh INTRODUCTION The adivasis of central India found themselves in the early nineteenth century in a time of flux, caught between the demands of competing hegemonies: the sub- empires of the Maratha Peshwa, and Bhonsle, Holkar and Scindia Rajas – all part of the Maratha confederacy – were in decline after the Second Anglo-Maratha War of 1803-05. -

Confronting the Violence Committed by Armed Opposition Groups

Nair: Confronting the Violence Committed by Armed Opposition Groups Confronting the Violence Committed by Armed Opposition Groups by Ravi Nair* 1 Human rights groups have limited their role to monitoring and protesting human rights violations committed by state actors.! With the emergence of armed opposition groups-such as the Sendero Luminoso in Peru2 and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in Sri Lanka 3 -that murder, torture, and destroy civil society in their respective regions, human rights entities must question whether they should broaden their mandate to include abuses committed by such groups. Focusing on the context of India, this article: (1) develops arguments encouraging human rights groups to critique abuses perpetrated by armed opposition groups; (2) suggests potential problems that may be encountered in making such criticisms; and (3) raises some reasons for caution by human rights organizations that condemn the actions of armed opposition groups. I. THE TRADITIONAL MANDATE OF HUMAN RIGHTS GROUPS 2 The primary, if not the exclusive, mandate of human rights groups around the world has been to monitor, highlight, and struggle against wanton violations of human rights perpetrated by agencies of the State.4 .Ravi Nair is the Executive Director of the South Asia Human Rights Documentation Centre ("SAHRDC") based in New Delhi, India <http://www.hri.ca/partners/sahrdc/index.htm>. 1. I use the term "state actor" to refer to states and those acting under the color of state authority. 2. See, e.g., Peru'sShining Path Kill Five in Grisly Attack on Border Town, AGENCE FRANCE- PRESSE, Dec. 8,1992, available in LEXIS, News Library, Arcnews File (describing an example of the terrorist activities of the Sendero Luminoso); Simon Strong, Where the Shining PathLeads, N.Y. -

243 Statement by Minister AUGUST 14, 1997 244 Notwithstanding What

243 Statement by Minister AUGUST 14, 1997 244 Notwithstanding what I have already said, I would like to SHRI PRAMOD MAHAJAN (Mumbai North-East) : Mr point out that since the dead body of Shri Sanjoy Ghosh has Speaker, Sir, Phoolan Devi is an honourable member of this not been recovered so far, in the strict legal sense, we cannot House. She is sitting outside, she must come inside. When declare that he is dead. Mulayam Singhji was the Chief Minister, he had withdrawn the cases filed against Phoolan Devi. As far as I know, as per law if Chief Minister or Home Minister withdraws a case and a [English] Court refuses to withdraw it, then, no Government can do anything in such a situation. The Court has opposed this SHRI KASHI RANA (Surat) : Sir, it is very important. All withdrawal. B.S.P. and BJP Governments have nothing to do the non-MPs from Gujarat ....(Interruptions) with it....(Interruptions) SHRI A.C. JOS (Idukki) : Sir, is it Bihar hour or is it Zero [English] Hour. MR. SPEAKER : You have made it clear DR. T. SUBBARAMI REDDY (Visakhapatnam) : Please see to it that Zero Hour is there. ....(Interruptions) SHRI A.C. JOS : We want no more of Bihar. We have had [Translation] enough of Bihar. THE MINISTER OF DEFENCE (SHRI MULAYAM SINGH DR. T. SUBBARAMI REDDY : We want Zero Hour. Every YADAV) : Pramod Mahajanji has mentioned my name in the day, we are talking only about Bihar. How long would we fight context of Phoolan Devi. We withdrew all cases and being a for Bihar? woman, on humanitarian ground ......(lnterruptions)\Ne are also not weak... -

No End to Crimes Against Dalits

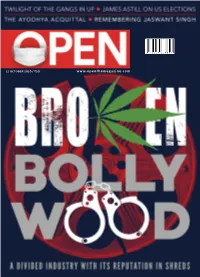

www.openthemagazine.com 50 12 OCTOBER /2020 OPEN VOLUME 12 ISSUE 40 12 OCTOBER 2020 CONTENTS 12 OCTOBER 2020 5 6 8 14 16 18 22 28 LOCOMOTIF INDRAPRASTHA MUMBAI TOUCHSTONE SOFT POWER WHISPERER IN MEMORIAM OPEN ESSAY The House of By Virendra Kapoor NOTEBOOK The sounds of our The Swami and the By Jayanta Ghosal Jaswant Singh Is it really over Jaswant Singh By Anil Dharker discontents Himalayas (1938-2020) for Trump? By S Prasannarajan By Keerthik Sasidharan By Makarand R Paranjape By MJ Akbar By James Astill and TCA Raghavan 32 32 BROKEN BOLLYWOOD Divided, self-referential in its storytelling, all too keen to celebrate mediocrity, its reputation in tatters and work largely stalled, the Mumbai film industry has hit rock bottom By Kaveree Bamzai 40 GRASS ROOTS Marijuana was not considered a social evil in the past and its return to respectability is inevitable in India By Madhavankutty Pillai 44 THE TWILIGHT OF THE GANGS 40 Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath has declared war on organised crime By Virendra Nath Bhatt 22 50 STATECRAFT Madhya Pradesh’s Covid opportunity By Ullekh NP 44 54 GLITTER IN GLOOM The gold loan market is cashing in on the pandemic By Nikita Doval 50 58 62 64 66 BETWEEN BODIES AND BELONGING MIND AND MACHINE THE JAISHANKAR DOCTRINE NOT PEOPLE LIKE US A group exhibition imagines Novels that intertwine artificial Rethinking India’s engagement Act two a multiplicity of futures intelligence with ethics with its enemies and friends By Rajeev Masand By Rosalyn D’Mello By Arnav Das Sharma By Siddharth Singh Cover by Saurabh Singh 12 OCTOBER 2020 www.openthemagazine.com 3 OPEN MAIL [email protected] EDITOR S Prasannarajan LETTER OF THE WEEK MANAGING EDITOR PR Ramesh C EXECUTIVE EDITOR Ullekh NP By any criterion, 2020 is annus horribilis (‘Covid-19: The EDITOR-AT-LARGE Siddharth Singh DEPUTY EDITORS Madhavankutty Pillai Surge’, October 5th, 2020). -

Faced by Truck Operators and Truck Drivers and Their Harressment

203 AUGUST 4, 1997 204 faced by truck operators and truck drivers and their members not to object to it. I will not say anything about harressment should immediately be stopped. court’s observation about me. [English] MR. DEPUTY SPEAKER : Please speak in brief. SHRI S.P. UDAYAPPAN (Ramanathapuram) : Mr. SHRIMATI PHOOLAN DEVI : I want to speak about Deputy-Speaker, Sir, on 17.7.1997 five fishermen of myself. Sir, I had surrendered in 1983. What was I, what Pamban were fishing near Vedaranyam well inside the happened to me and in the past, I will not speak anything Indian territory. All of a sudden, at about 5 p.m., the Sri on these things. But I did surrender in 1983 with Lankan Army personnel came there in a helicopter and preconditions. The Madhya Pradesh Government had started firing at their boat. As a result of this firing, two promised me that likewise the dacoits surrendered in fishermen labaraj and Francis, belonging to Pamban, 1972 which included Madho Singh, Mohar Singh, died on the spot and three others were seriously injured. Tehsildar Singh and many others and that Surrender was made possible at the instance of Acharya Binobha Sir, a large number of fishermen of Pamban and Bhave. He was facing litigations in three states viz Uttar Rameswaram have been brutally attacked and Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan and all these mercilessly killed by the Sri Lankan Army and Navy in cases were heard at the same place i.e. inside the the recent months. The Sri Lankan Government have Madhya Pradesh Central Jail. -

Indian Cinema and the Bahujan Spectatorship

ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 Indian Cinema and the Bahujan Spectatorship JYOTI NISHA Jyoti Nisha ([email protected]) is a writer, director, and producer. She directed well- known documentary film "B R Ambedkar—Now and Then." Vol. 55, Issue No. 20, 16 May, 2020 Bahujan spectatorship relates to an oppositional gaze and a political strategy of Bahujans to reject the Brahminical representation of caste and marginalised communities in Indian cinema. It is also an inverted methodology to document a different sociopolitical Bahujan experience of consuming popular cinema. “Indians today are governed by two different ideologies. Their political ideal set in the preamble of the Constitution affirms a life of liberty, equality and fraternity. Their social ideal embodied in their religion denies them.” (Narake et al 2003) This dual imagination of Indian nation, as B R Ambedkar forewarned, finds its manifestation even on the silver screen. India’s popular imagination of its colonial past has been that of a “haloed” history of Indian nationalism. Ambedkar has not been part of this popular imagination, and neither do the politics, history, and social movements of the marginalised. The assertion of the marginalised has hardly made it to the pre- and post-independence Indian cinema. Largely, the image of Indian nationalism in the popular imagination has been ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 that of M K Gandhi, and Ambedkar and his social justice movements against Brahmanism have been absent from the public conscience. This gaze of “othering,” silencing, and appropriating the existence of history, knowledge, and symbols of the marginalised communities have been tools employed by the upper-caste film-makers deliberately. -

Bandit Queen

This article was downloaded by: [Anna Lindh-biblioteket] On: 31 July 2015, At: 00:24 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London, SW1P 1WG Small Wars & Insurgencies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fswi20 Bandit Queen: Cinematic representation of social banditry in India Shanthie Mariet D'Souzaa & Bibhu Prasad Routraya a Mantraya.org, Mantraya, New Delhi, India Published online: 21 Jul 2015. Click for updates To cite this article: Shanthie Mariet D'Souza & Bibhu Prasad Routray (2015) Bandit Queen: Cinematic representation of social banditry in India, Small Wars & Insurgencies, 26:4, 688-701, DOI: 10.1080/09592318.2015.1050822 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2015.1050822 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

![Arena of Colony Ponzanesi EN2009 [Updated 2018]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2461/arena-of-colony-ponzanesi-en2009-updated-2018-4092461.webp)

Arena of Colony Ponzanesi EN2009 [Updated 2018]

The arena of the colony: Phoolan Devi and postcolonial critique 6 Sandra Ponzanesi 6.1 Poster of the film Bandit Queen, about the life of Phoolan Devi. In February 1994, a woman of legendary status, Phoolan Devi, was released from prison under the full mediatic blow of the Indian nation.1 Better known as the Bandit Queen, the Avenging Angel, or the Rebel of the Ravines, Devi made a remarkable transformation from lower-caste fisherman’s daughter (mallah) to member of the Indian Parliament in 1996. With a red bandana on her head and a rifle in her hand, Phoolan Devi had become the popular embodiment of cruel and bloodthirsty goddesses such as Kali or Durga. The arena of the colony • 85 Kali is the goddess of destruction, and the patron of dacoits (bandits). She reputedly slaughtered her enemies with her thousand arms and with a smile on her face. Durga is the goddess of war and notorious for her slaughter of demons. Phoolan Devi’s larger- than-life image is that of a victim of caste oppression and gender exploitation, who fought back first by resorting to acts of revenge and later by moving on to the political plain. There, she metamorphosized into a phenomenal leader who waged a persistent struggle in the cause of the weak and downtrodden. Married off at eleven years of age to a man three times her age, Devi ran away after being abused and was consequently abandoned by her family. By the time she was twenty years old she had been subjected to several sexual assaults, both from higher caste men (thakurs or landowners) and from police officers during her unexplained arrests.