Indian Cinema and the Bahujan Spectatorship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supreme Court of India Bobby Art International, Etc Vs Om Pal Singh Hoon & Ors on 1 May, 1996 Author: Bharucha Bench: Cji, S.P

Supreme Court of India Bobby Art International, Etc vs Om Pal Singh Hoon & Ors on 1 May, 1996 Author: Bharucha Bench: Cji, S.P. Bharucha, B.N. Kirpal PETITIONER: BOBBY ART INTERNATIONAL, ETC. Vs. RESPONDENT: OM PAL SINGH HOON & ORS. DATE OF JUDGMENT: 01/05/1996 BENCH: CJI, S.P. BHARUCHA , B.N. KIRPAL ACT: HEADNOTE: JUDGMENT: WITH CIVIL APPEAL NOS. 7523, 7525-27 AND 7524 (Arising out of SLP(Civil) No. 8211/96, SLP(Civil) No. 10519-21/96 (CC No. 1828-1830/96 & SLP(C) No. 9363/96) J U D G M E N T BHARUCHA, J. Special leave granted. These appeals impugn the judgment and order of a Division Bench of the High Court of Delhi in Letters Patent appeals. The Letters Patent appeals challenged the judgment and order of a learned single judge allowing a writ petition. The Letters Patent appeals were dismissed, subject to a direction to the Union of India (the second respondent). The writ petition was filed by the first respondent to quash the certificate of exhibition awarded to the film "Bandit Queen" and to restrain its exhibition in India. The film deals with the life of Phoolan Devi. It is based upon a true story. Still a child, Phoolan Devi was married off to a man old enough to be her father. She was beaten and raped by him. She was tormented by the boys of the village; and beaten by them when she foiled the advances of one of them. A village panchayat called after the incident blamed Phoolan Devi for attempting to entice the boy, who belonged to a higher caste. -

Missing Lawyer at Risk of Torture

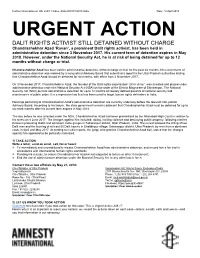

Further information on UA: 248/17 Index: ASA 20/8191/2018 India Date: 10 April 2018 URGENT ACTION DALIT RIGHTS ACTIVIST STILL DETAINED WITHOUT CHARGE Chandrashekhar Azad ‘Ravan’, a prominent Dalit rights activist, has been held in administrative detention since 3 November 2017. His current term of detention expires in May 2018. However, under the National Security Act, he is at risk of being detained for up to 12 months without charge or trial. Chandrashekhar Azad has been held in administrative detention, without charge or trial, for the past six months. His current term of administrative detention was ordered by a non-judicial Advisory Board that submitted a report to the Uttar Pradesh authorities stating that Chandrashekhar Azad should be detained for six months, with effect from 2 November 2017. On 3 November 2017, Chandrashekhar Azad, the founder of the Dalit rights organisation “Bhim Army”, was arrested and placed under administrative detention under the National Security Act (NSA) on the order of the District Magistrate of Saharanpur. The National Security Act (NSA) permits administrative detention for up to 12 months on loosely defined grounds of national security and maintenance of public order. It is a repressive law that has been used to target human rights defenders in India. Hearings pertaining to Chandrashekhar Azad’s administrative detention are currently underway before the relevant non-judicial Advisory Board. According to his lawyer, the state government remains adamant that Chandrashekhar Azad must be detained for up to six more months after his current term expires in May 2018. The day before he was arrested under the NSA, Chandrashekhar Azad had been granted bail by the Allahabad High Court in relation to his arrest on 8 June 2017. -

Western Uttar Pradesh: Caste Arithmetic Vs Nationalism

VERDICT 2019 Western Uttar Pradesh: Caste Arithmetic vs Nationalism SMITA GUPTA Samajwadi Party patron Mulayam Singh Yadav exchanges greetings with Bahujan Samaj Party supremo Mayawati during their joint election campaign rally in Mainpuri, on April 19, 2019. Photo: PTI In most of the 26 constituencies that went to the polls in the first three phases of the ongoing Lok Sabha elections in western Uttar Pradesh, it was a straight fight between the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) that currently holds all but three of the seats, and the opposition alliance of the Samajwadi Party, the Bahujan Samaj Party and the Rashtriya Lok Dal. The latter represents a formidable social combination of Yadavs, Dalits, Muslims and Jats. The sort of religious polarisation visible during the general elections of 2014 had receded, Smita Gupta, Senior Fellow, The Hindu Centre for Politics and Public Policy, New Delhi, discovered as she travelled through the region earlier this month, and bread and butter issues had surfaced—rural distress, delayed sugarcane dues, the loss of jobs and closure of small businesses following demonetisation, and the faulty implementation of the Goods and Services Tax (GST). The Modi wave had clearly vanished: however, BJP functionaries, while agreeing with this analysis, maintained that their party would have been out of the picture totally had Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his message of nationalism not been there. travelled through the western districts of Uttar Pradesh earlier this month, conversations, whether at district courts, mofussil tea stalls or village I chaupals1, all centred round the coming together of the Samajwadi Party (SP), the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) and the Rashtriya Lok Dal (RLD). -

“Low” Caste Women in India

Open Cultural Studies 2018; 2: 735-745 Research Article Jyoti Atwal* Embodiment of Untouchability: Cinematic Representations of the “Low” Caste Women in India https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2018-0066 Received May 3, 2018; accepted December 7, 2018 Abstract: Ironically, feudal relations and embedded caste based gender exploitation remained intact in a free and democratic India in the post-1947 period. I argue that subaltern is not a static category in India. This article takes up three different kinds of genre/representations of “low” caste women in Indian cinema to underline the significance of evolving new methodologies to understand Black (“low” caste) feminism in India. In terms of national significance, Acchyut Kanya represents the ambitious liberal reformist State that saw its culmination in the constitution of India where inclusion and equality were promised to all. The movie Ankur represents the failure of the state to live up to the postcolonial promise of equality and development for all. The third movie, Bandit Queen represents feminine anger of the violated body of a “low” caste woman in rural India. From a dacoit, Phoolan transforms into a constitutionalist to speak about social justice. This indicates faith in Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s India and in the struggle for legal rights rather than armed insurrection. The main challenge of writing “low” caste women’s histories is that in the Indian feminist circles, the discourse slides into salvaging the pain rather than exploring and studying anger. Keywords: Indian cinema, “low” caste feminism, Bandit Queen, Black feminism By the late nineteenth century due to certain legal and socio-religious reforms,1 space of the Indian family had been opened to public scrutiny. -

25 May 2018 Hon'ble Chairperson, Shri Justice HL

25 May 2018 Hon’ble Chairperson, Shri Justice H L Dattu National Human Rights Commission, Block –C, GPO Complex, INA New Delhi- 110023 Respected Hon’ble Chairperson, Subject: Continued arbitrary detention and harassment of Dalit rights activist, Chandrashekhar Azad Ravana The Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA) appeals the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) to urgently carry out an independent investigation into the continued detention of Dalit human rights defender, Chandrashekhar Azad Ravan, in Saharanpur, Uttar Pradesh State, to furnish the copy of the investigation report before the non-judicial tribunal established under the NSA, and to move the court to secure his release. Chandrashekhar is detained under the National Security Act (NSA) without charge or trial. FORUM-ASIA is informed that in May 2017, Dalit and Thakur communities were embroiled in caste - based riots instigated by the dominant Thakur caste in Saharanpur city of Uttar Pradesh. The riots resulted in one death, several injuries and a number of Dalit homes being burnt. Following the protests, 40 prominent activists and leaders of 'Bhim Army', a Dalit human rights organisation, were arrested but later granted bail. Chandrashekhar Azad Ravan, a young lawyer and co-founder of ‘Bhim Army’, was arrested on 8 June 2017 following a charge sheet filed by a Special Investigation Team (SIT) constituted to investigate the Saharanpur incident. He was framed with multiple charges under the Indian Penal Code 147 (punishment for rioting), 148 (rioting armed with deadly weapon) and 153A among others, for his alleged participation in the riots. Even though Chandrashekhar was not involved in the protests, and wasn't present during the riot, he was detained on 8 June. -

Unit Indian Cinema

Popular Culture .UNIT INDIAN CINEMA Structure Objectives Introduction Introducing Indian Cinema 13.2.1 Era of Silent Films 13.2.2 Pre-Independence Talkies 13.2.3 Post Independence Cinema Indian Cinema as an Industry Indian Cinema : Fantasy or Reality Indian Cinema in Political Perspective Image of Hero Image of Woman Music And Dance in Indian Cinema Achievements of Indian Cinema Let Us Sum Up Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises A 13.0 OBJECTIVES This Unit discusses about Indian cinema. Indian cinema has been a very powerful medium for the popular expression of India's cultural identity. After reading this Unit you will be able to: familiarize yourself with the achievements of about a hundred years of Indian cinema, trace the development of Indian cinema as an industry, spell out the various ways in which social reality has been portrayed in Indian cinema, place Indian cinema in a political perspective, define the specificities of the images of men and women in Indian cinema, . outline the importance of music in cinema, and get an idea of the main achievements of Indian cinema. 13.1 INTRODUCTION .p It is not possible to fully comprehend the various facets of modern Indan culture without understanding Indian cinema. Although primarily a source of entertainment, Indian cinema has nonetheless played an important role in carving out areas of unity between various groups and communities based on caste, religion and language. Indian cinema is almost as old as world cinema. On the one hand it has gdted to the world great film makers like Satyajit Ray, , it has also, on the other hand, evolved melodramatic forms of popular films which have gone beyond the Indian frontiers to create an impact in regions of South west Asia. -

Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada

Responses to Information Requests - Immigration and Refugee Board of... https://irb-cisr.gc.ca/en/country-information/rir/Pages/index.aspx?doc=4... Responses to Information Requests - Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada India: Treatment of Dalits by society and authorities; availability of state protection (2016- January 2020) 1. Overview According to sources, the term Dalit means "'broken'" or "'oppressed'" (Dalit Solidarity n.d.a; MRG n.d.; Navsarjan Trust n.d.a). Sources indicate that this group was formerly referred to as "'untouchables'" (Dalit Solidarity n.d.a; MRG n.d.; Navsarjan Trust n.d.a). They are referred to officially as "Scheduled Castes" (India 13 July 2006, 1; MRG n.d.; Navsarjan Trust n.d.a). The Indian National Commission for Scheduled Castes (NCSC) identified that Scheduled Castes are communities that "were suffering from extreme social, educational and economic backwardness arising out of [the] age-old practice of untouchability" (India 13 July 2006, 1). The Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI) [1] indicates that the list of groups officially recognized as Scheduled Castes, which can be modified by the Parliament, varies from one state to another, and can even vary among districts within a state (CHRI 2018, 15). According to the 2011 Census of India [the most recent census (World Population Review [2019])], the Scheduled Castes represent 16.6 percent of the total Indian population, or 201,378,086 persons, of which 76.4 percent are in rural areas (India 2011). The census further indicates that the Scheduled Castes constitute 18.5 percent of the total rural population, and 12.6 percent of the total urban population in India (India 2011). -

'Ambedkar's Constitution': a Radical Phenomenon in Anti-Caste

Article CASTE: A Global Journal on Social Exclusion Vol. 2 No. 1 pp. 109–131 brandeis.edu/j-caste April 2021 ISSN 2639-4928 DOI: 10.26812/caste.v2i1.282 ‘Ambedkar’s Constitution’: A Radical Phenomenon in Anti-Caste Discourse? Anurag Bhaskar1 Abstract During the last few decades, India has witnessed two interesting phenomena. First, the Indian Constitution has started to be known as ‘Ambedkar’s Constitution’ in popular discourse. Second, the Dalits have been celebrating the Constitution. These two phenomena and the connection between them have been understudied in the anti-caste discourse. However, there are two generalised views on these aspects. One view is that Dalits practice a politics of restraint, and therefore show allegiance to the Constitution which was drafted by the Ambedkar-led Drafting Committee. The other view criticises the constitutional culture of Dalits and invokes Ambedkar’s rhetorical quote of burning the Constitution. This article critiques both these approaches and argues that none of these fully explores and reflects the phenomenon of constitutionalism by Dalits as an anti-caste social justice agenda. It studies the potential of the Indian Constitution and responds to the claim of Ambedkar burning the Constitution. I argue that Dalits showing ownership to the Constitution is directly linked to the anti-caste movement. I further argue that the popular appeal of the Constitution has been used by Dalits to revive Ambedkar’s legacy, reclaim their space and dignity in society, and mobilise radically against the backlash of the so-called upper castes. Keywords Ambedkar, Constitution, anti-caste movement, constitutionalism, Dalit Introduction Dr. -

Joint Submission to the United Nations Human Rights Committee, Adoption of List of Issues

JOINT SUBMISSION TO THE UNITED NATIONS HUMAN RIGHTS COMMITTEE, ADOPTION OF LIST OF ISSUES 126TH SESSION, (01 to 26 July 2019) JOINTLY SUBMITTED BY NATIONAL DALIT MOVEMENT FOR JUSTICE-NDMJ (NCDHR) AND INTERNATIONAL DALIT SOLIDARITY NETWORK-IDSN STATE PARTY: INDIA Introduction: National Dalit Movement for Justice (NDMJ)-NCDHR1 & International Dalit Solidarity Network (IDSN) provide the below information to the United Nations (UN) Human Rights Committee (the Committee) ahead of the adoption of the list of issues for the 126th session for the state party - INDIA. This submission sets out some of key concerns about violations of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (the Covenant) vis-à- vis the Constitution of India with regard to one of the most vulnerable communities i.e, Dalit's and Adivasis, officially termed as “Scheduled Castes” and “Scheduled Tribes”2. Prohibition of Traffic in Human Beings and Forced Labour: Article 8(3) ICCPR Multiple studies have found that Dalits in India have a significantly increased risk of ending in modern slavery including in forced and bonded labour and child labour. In Tamil Nadu, the majority of the textile and garment workforce is women and children. Almost 60% of the Sumangali workers3 belong to the so- called ‘Scheduled Castes’. Among them, women workers are about 65% mostly unskilled workers.4 There are 1 National Dalit Movement for Justice-NCDHR having its presence in 22 states of India is committed to the elimination of discrimination based on work and descent (caste) and work towards protection and promotion of human rights of Scheduled Castes (Dalits) and Scheduled Tribes (Adivasis) across India. -

The Hunt for Phoolan Devi

• COVER STORY THE HUNT FOR \ • .\-~ !PHOOLAN '--------I OEVI On theafternoonof31 March, when on an informer'a' rrp-Off the police surrounded Gulauli village in UP)j' Jalaun district, they thought they would finally, get the dacoit queen Phoolan Devi; but she slipped awa;}!. Nirmal Mitra visited Gulauli to report on the massive hunt, and the ~~~ .. encounte~ j.n.which most of Phoolan's gang was wiped out. ~ hoolan Devi. the dacoit PhoOian Devi had been arrested and queen. is a desperate was being brought 10 UP's capital by ~ ~\ woman loday, fun ninA for helicopter; it was later discovered to her life. The whole police be an A.pril Fool's joke. Even the news force of Unar Pradesh agencies had been taken in by this se~msP to be after her; she is every.- prank.) one's prize catcli. More than half of The manner in which Phoolan Devi her small gang has already been wiped escaped from the police on 31 March out in one encounter with the police makes an ahsolutely fascinating story. after another during this war that the typical of all that has come to be police have launched on dacoits after associated with dacoits-violence. wit. the bloody revenge that Phoolan Devi presence of mind, and that important took on the Behmai rhaJcurs (see Sun- mgredient, a sense of honour. It seems day 15 March) who had once insulted straight tiut of a Bombay film. and humiliated her. Other important Raba Mustaqim (he was a Muslim) dacoit leaders are angry':with her; by was killed on 4 March near Akbarpur this one outrage. -

What Is Mayawati's Future In

DAILY SUARGAM | JAMMU EDIT-OPINION MONDAY | JUNE 14, 2021 6 EDITORIAL 100-YEAR JOURNEY~I SANJUKTA DASGUPTA ophy, medieval mysticism, Significantly, the recent clubbed together as joint ven- can education have a holistic ration through the arts have Islamic culture, Zoroastrian emphasis on skill develop- tures primarily discourage objective that recognizes the been rejected in favour of a VDC issue Ahundred years ago, in philosophy, Bengali literature ment, entrepreneurship, critical thinking and freedom multiple intersections of race, pedagogy of force-feeding 1921, Rabindranath Tagore and history, Hindustani liter- start-ups, eliding the need for of configuring ideas and class, colour, caste, creed, reli- for standardized national founded Visva Bharati ature, Vedic and Classical engagement in humanities interfere with creative free- gion, gender and sexuality education.” In a more direct University at Santiniketan, Sanskrit, Pali, Prakrit, and social sciences that dom. So, in unequivocal that can construct a complete awareness campaign regard- It is sad and strange that Village Bolpur, in undivided Bengal. Chinese, Tibetan, Persian, enable breaking free from terms, Nussbaum observes, human being rather than an ing the absolute necessity of Visva Bharati is often regard- Arabic, German, Latin and shibboleths and stereotypes, “Thirsty for national profit, automaton? The Universal literature studies as an essen- Defence Committees (VDC) members ed as the first international Hindi formed its areas of may not have found favour nations and -

Tagore & Cinema

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/286452770 Tagore, Cinema and the Poetry of Movement Article · March 2015 CITATIONS READS 0 957 1 author: Indranil Chakrabarty LV Prasad Film & TV Academy 8 PUBLICATIONS 1 CITATION SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Narrative Strategies in the Postmodern Biopic: History and Counter History View project All content following this page was uploaded by Indranil Chakrabarty on 11 December 2015. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. This essay, published in ‘Lensight’ (Jan-Mar, 2015 issue), was presented at a JNU conference titled ‘Rethinking Tagore’ in November, 2011.The essay that follows is a modified version of that presentation. TAGORE, CINEMA AND THE POETRY OF MOVEMENT Indranil Chakravarty Introduction It must have been almost impossible to be a writer in the twentieth century in any part of the world without some kind of response to the new and emerging narrative form called cinema or ‘motion pictures’. As cinema’s birth coincided with the onset of the 20th century, its own development and growth as an art form as well as an industry went almost hand-in-hand with the vicissitudes of social, political and cultural developments in the past century. The popular and frivolous base of cinema led most ‘high brow’ writers to turn their back towards it and many of them were oblivious of the extraordinary narrative experimentations that were being explored in this new form of expression. Whether cinema could at all be considered a valid ‘art form’ was debated till the 1960s though through the 1920s and 1930s, there was a sporadic phenomenon – mainly in Europe and USA - of painters, theatre directors and writers collaborating on film projects.