Bandit Queen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stenographer (Post Code-01)

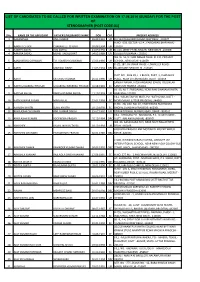

LIST OF CANDIDATES TO BE CALLED FOR WRITTEN EXAMINATION ON 17.08.2014 (SUNDAY) FOR THE POST OF STENOGRAPHER (POST CODE-01) SNo. NAME OF THE APPLICANT FATHER'S/HUSBAND'S NAME DOB CAT. PRESENT ADDRESS 1 AAKANKSHA ANIL KUMAR 28.09.1991 UR B II 544 RAGHUBIR NAGAR NEW DELHI -110027 H.NO. -539, SECTOR -15-A , FARIDABAD (HARYANA) - 2 AAKRITI CHUGH CHARANJEET CHUGH 30.08.1994 UR 121007 3 AAKRITI GOYAL AJAI GOYAL 21.09.1992 UR B -116, WEST PATEL NAGAR, NEW DELHI -110008 4 AAMIRA SADIQ MOHD. SADIQ BHAT 04.05.1989 UR GOOSU PULWAMA - 192301 WZ /G -56, UTTAM NAGAR NEAR, M.C.D. PRIMARY 5 AANOUKSHA GOSWAMI T.R. SOMESH GOSWAMI 15.03.1995 UR SCHOOL, NEW DELHI -110059 R -ZE, 187, JAI VIHAR PHASE -I, NANGLOI ROAD, 6 AARTI MAHIPAL SINGH 21.03.1994 OBC NAJAFGARH NEW DELHI -110043 PLOT NO. -28 & 29, J -1 BLOCK, PART -1, CHANAKYA 7 AARTI SATENDER KUMAR 20.01.1990 UR PLACE, NEAR UTTAM NAGAR, DELHI -110059 SANJAY NAGAR, HOSHANGABAD (GWOL TOLI) NEAR 8 AARTI GULABRAO THOSAR GULABRAO BAKERAO THOSAR 30.08.1991 SC SANTOSHI TEMPLE -461001 I B -35, N.I.T. FARIDABAD, NEAR RAM DHARAM KANTA, 9 AASTHA AHUJA RAKESH KUMAR AHUJA 11.10.1993 UR HARYANA -121001 VILL. -MILAK TAJPUR MAFI, PO. -KATHGHAR, DISTT. - 10 AATIK KUMAR SAGAR MADAN LAL 22.01.1993 SC MORADABAD (UTTAR PRADESH) -244001 H.NO. -78, GALI NO. 02, KHATIKPURA BUDHWARA 11 AAYUSHI KHATRI SUNIL KHATRI 10.10.1993 SC BHOPAL (MADHYA PRADESH) -462001 12 ABHILASHA CHOUHAN ANIL KUMAR SINGH 25.07.1992 UR RIYASAT PAWAI, AURANGABAD, BIHAR - 824101 VILL. -

Darcus Howe: a Political Biography

Bunce, Robin, and Paul Field. "Authors' Preface." Darcus Howe: A Political Biography. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014. viii–x. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 29 Sep. 2021. <>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 29 September 2021, 20:11 UTC. Copyright © Robin Bunce and Paul Field 2014. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. Authors ’ Preface Writing this book has involved many wonderful experiences. Hours in archives are, of course, the historian ’ s delight, and we thank the staff at the National Archives, the Institute of Race Relations, the George Padmore Institute, the British Library, the Colindale Newspaper Archive, Warwick University Library, Cambridge University Library, the Butler Library at the Columbia University and the archives of the Oilfi eld Workers Trade Union of Trinidad and Tobago, to name but a few. We have spent many hours being entertained by our interviewees. Early on in the project, we had the good fortune to spend an aft ernoon with Farrukh Dhondy. ‘ I expect you want me to tell you all the scandal, ’ was his opener. We earnestly assured him that we were writing a serious political piece, adding that we couldn ’ t believe that there would be enough scandal to fi ll a single page. ‘ Th ere ’ s enough to fi ll seven volumes! ’ , he retorted. One of the stranger experiences, only obliquely related to the project, was an Equality and Diversity training session that one of us was compelled to attend in the summer of 2011. -

Supreme Court of India Bobby Art International, Etc Vs Om Pal Singh Hoon & Ors on 1 May, 1996 Author: Bharucha Bench: Cji, S.P

Supreme Court of India Bobby Art International, Etc vs Om Pal Singh Hoon & Ors on 1 May, 1996 Author: Bharucha Bench: Cji, S.P. Bharucha, B.N. Kirpal PETITIONER: BOBBY ART INTERNATIONAL, ETC. Vs. RESPONDENT: OM PAL SINGH HOON & ORS. DATE OF JUDGMENT: 01/05/1996 BENCH: CJI, S.P. BHARUCHA , B.N. KIRPAL ACT: HEADNOTE: JUDGMENT: WITH CIVIL APPEAL NOS. 7523, 7525-27 AND 7524 (Arising out of SLP(Civil) No. 8211/96, SLP(Civil) No. 10519-21/96 (CC No. 1828-1830/96 & SLP(C) No. 9363/96) J U D G M E N T BHARUCHA, J. Special leave granted. These appeals impugn the judgment and order of a Division Bench of the High Court of Delhi in Letters Patent appeals. The Letters Patent appeals challenged the judgment and order of a learned single judge allowing a writ petition. The Letters Patent appeals were dismissed, subject to a direction to the Union of India (the second respondent). The writ petition was filed by the first respondent to quash the certificate of exhibition awarded to the film "Bandit Queen" and to restrain its exhibition in India. The film deals with the life of Phoolan Devi. It is based upon a true story. Still a child, Phoolan Devi was married off to a man old enough to be her father. She was beaten and raped by him. She was tormented by the boys of the village; and beaten by them when she foiled the advances of one of them. A village panchayat called after the incident blamed Phoolan Devi for attempting to entice the boy, who belonged to a higher caste. -

Saurashtra University Library Service

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Etheses - A Saurashtra University Library Service Saurashtra University Re – Accredited Grade ‘B’ by NAAC (CGPA 2.93) Kinger, Anil H., 2008, “The Minorities and their Voices: A Critical Study of the Contemporary Indian English Writing with rererence to the Novels of Salman Rushdie, Rohinton Mistry, I. Allan Sealy and Esther David”, thesis PhD, Saurashtra University http://etheses.saurashtrauniversity.edu/id/834 Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Saurashtra University Theses Service http://etheses.saurashtrauniversity.edu [email protected] © The Author THE MINORITIES AND THEIR VOICES: A CRITICAL STUDY OF THE CONTEMPORARY INDIAN ENGLISH WRITING WITH REFERENCE TO THE NOVELS OF SALMAN RUSHDIE, ROHINTON MISTRY, I. ALLAN SEALY AND ESTHER DAVID DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO SAURASHTRA UNIVERSITY, RAJKOT FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SUBMITTED BY: ANIL HARILAL KINGER LECTURER & HEAD SHRI P. D. MALAVIYA COLLEGE OF COMMERCE, RAJKOT SUPERVISED BY: DR. KAMAL H. MEHTA PROFESSOR & HEAD DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH & COMPARATIVE LITERARY STUDIES, SAURASHTRA UNIVERSITY, RAJKOT. -

Self-Determination Activist and Writer Darcus Howe

In Memoriam: Self-Determination Activist and Writer Darcus Howe The broadcaster and writer Darcus Howe, who has died aged 74, once described himself as having come from Trinidad on a “civilizing mission”, to teach Britons to live in a harmonious and diverse society. His aims were radical, and he brought them into the mainstream by articulating fundamental principles in a strikingly outspoken way. After his initial experience of racial tension in Britain at the start of the 1960s, Howe became active in the Black Power movement in the US and the Caribbean. In August 1970, having returned to London, he organized, with Althea Jones-Lecointe and the British Black Panthers, a campaign in defense of the Mangrove restaurant. Established and run by Frank Crichlow, the Mangrove was a small piece of decolonized territory in Notting Hill, west London. When police attempted to close it, Howe came to his friend’s aid, organizing a march. Entirely peaceful until the police intervened in overwhelming numbers, it led to a spontaneous melee, the melee to arrests, and the arrests to the biggest Black Power trial in British history. 2 Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies, vol.10, no.3, May 2017 For 55 days Howe and Jones-Lecointe led the defense of the Mangrove nine – themselves, Crichlow and six others – from the dock of the Old Bailey. Howe demanded an all-Black jury, a claim he rooted in the Magna Carta. The judge rejected this, but the nine had stamped their authority on the case. Howe subjected the prosecution to forensic scrutiny. -

“Low” Caste Women in India

Open Cultural Studies 2018; 2: 735-745 Research Article Jyoti Atwal* Embodiment of Untouchability: Cinematic Representations of the “Low” Caste Women in India https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2018-0066 Received May 3, 2018; accepted December 7, 2018 Abstract: Ironically, feudal relations and embedded caste based gender exploitation remained intact in a free and democratic India in the post-1947 period. I argue that subaltern is not a static category in India. This article takes up three different kinds of genre/representations of “low” caste women in Indian cinema to underline the significance of evolving new methodologies to understand Black (“low” caste) feminism in India. In terms of national significance, Acchyut Kanya represents the ambitious liberal reformist State that saw its culmination in the constitution of India where inclusion and equality were promised to all. The movie Ankur represents the failure of the state to live up to the postcolonial promise of equality and development for all. The third movie, Bandit Queen represents feminine anger of the violated body of a “low” caste woman in rural India. From a dacoit, Phoolan transforms into a constitutionalist to speak about social justice. This indicates faith in Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s India and in the struggle for legal rights rather than armed insurrection. The main challenge of writing “low” caste women’s histories is that in the Indian feminist circles, the discourse slides into salvaging the pain rather than exploring and studying anger. Keywords: Indian cinema, “low” caste feminism, Bandit Queen, Black feminism By the late nineteenth century due to certain legal and socio-religious reforms,1 space of the Indian family had been opened to public scrutiny. -

British Black Power

SOR0010.1177/0038026119845550The Sociological ReviewNarayan 845550research-article2019 The Sociological Article Review The Sociological Review 2019, Vol. 67(5) 945 –967 British Black Power: © The Author(s) 2019 Article reuse guidelines: The anti-imperialism of sagepub.com/journals-permissions DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026119845550 10.1177/0038026119845550 political blackness and the journals.sagepub.com/home/sor problem of nativist socialism John Narayan School of Social Sciences, Birmingham City University, UK Abstract The history of the US Black Power movement and its constituent groups such as the Black Panther Party has recently gone through a process of historical reappraisal, which challenges the characterization of Black Power as the violent, misogynist and negative counterpart to the Civil Rights movement. Indeed, scholars have furthered interest in the global aspects of the movement, highlighting how Black Power was adopted in contexts as diverse as India, Israel and Polynesia. This article highlights that Britain also possessed its own distinctive form of Black Power movement, which whilst inspired and informed by its US counterpart, was also rooted in anti-colonial politics, New Commonwealth immigration and the onset of decolonization. Existing sociological narratives usually locate the prominence and visibility of British Black Power and its activism, which lasted through the 1960s to the early 1970s, within the broad history of UK race relations and the movement from anti-racism to multiculturalism. However, this characterization neglects how such Black activism conjoined explanations of domestic racism with issues of imperialism and global inequality. Through recovering this history, the article seeks to bring to the fore a forgotten part of British history and also examines how the history of British Black Power offers valuable lessons about how the politics of anti-racism and anti-imperialism should be united in the 21st century. -

East End Immigrants and the Battle for Housing Sarah Glynn 2004

East End Immigrants and the Battle for Housing Sarah Glynn 2004 East End Immigrants and the Battle for Housing: a comparative study of political mobilisation in the Jewish and Bengali communities The final version of this paper was published in the Journal of Historical Geography 31 pp 528 545 (2005) Abstract Twice in the recent history of the East End of London, the fight for decent housing has become part of a bigger political battle. These two very different struggles are representative of two important periods in radical politics – the class politics, tempered by popularfrontism that operated in the 1930s, and the new social movement politics of the seventies. In the rent strikes of the 1930s the ultimate goal was Communism. Although the local Party was disproportionately Jewish, Communist theory required an outward looking orientation that embraced the whole of the working class. In the squatting movement of the 1970s political organisers attempted to steer the Bengalis onto the path of Black Radicalism, championing separate organisation and turning the community inwards. An examination of the implementation and consequences of these different movements can help us to understand the possibilities and problems for the transformation of grassroots activism into a broader political force, and the processes of political mobilisation of ethnic minority groups. Key Words Tower Hamlets, political mobilisation, oral history, Bengalis, Jews, housing In London’s East End, housing crises are endemic. The fight for adequate and decent housing is fundamental, but for most of those taking part its goals do not extend beyond the satisfaction of housing needs. -

1000-Provisionally Selected Under Top Class Scholarship-2018-19 Slno

ANNEXURE-B 1000-Provisionally selected under Top Class Scholarship-2018-19 Slno. Scheme Slno. Application ID Applicant Name Father's Name Current Institution Current Course Name Stream 1 E&T-12th-01 TS201819009436545 AJMEERA SWARNA NAYAK AJMEERA SHANKAR NAIK INDIAN INSTITUTE OF BACHELOR OF ENGINEERING(CIVIL Engg.&Tech TECHNOLOGY, ENGINEERING) HYDERABAD/MEDAK/TELANGAN A 2 E&T-12th-02 TS201819003660949 KORRA JAGAN BABU KORRA PANDU NAIK NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF B.TECH (COMPUTER SCIENCE & Engg.&Tech TECHNOLOGY,SURATHKAL, ENGINEERING) KARNATAKA/DAKSHINA KANNADA/KARNATAKA 3 E&T-12th-03 AP201819001267548 SUGANA DASARI DASARI DASU BABU NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF BACHELOR OF Engg.&Tech TECHNOLOGY, TECHNOLOGY(ELECTRICAL & TIRUCHIRAPALLI/TIRUCHIRAPPAL ELECTRONICS ENGINEERING(EEE)) LI/TAMIL NADU 4 E&T-12th-04 AP201819008318271 BUKKE JAI SINDHU KRISHNA BUKKE RAMAKRISHNA INDIAN INSTITUTE OF BACHELOR OF Engg.&Tech TECHNOLOGY, ENGINEERING(COMPUTER SCIENCE & BHUBANESHWAR/KHORDHA/ODI ENGINEERING) SHA 5 E&T-12th-05 TS201819000222715 BANOTH GANESH BANOTH SUNDER NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF BACHELOR OF Engg.&Tech TECHNOLOGY, TECHNOLOGY(ELECTRICAL WARANGAL/WARANGAL ENGINEERING) RURAL/TELANGANA 6 E&T-12th-06 AP201819001748150 RAMAVATHU PAVAN KUMAR R manthru naik INDIAN INSTITUTE OF Bachelor of Technology (Computer Engg.&Tech NAIK TECHNOLOGY, Engineering) CHENNAI/CHENNAI/TAMIL NADU 7 E&T-12th-07 AP201819002674796 POTLURU PRAVEEN POTLURU SURESH NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF BACHELOR OF Engg.&Tech TECHNOLOGY, AGARTALA/WEST TECHNOLOGY(ELECTRONICS AND TRIPURA/TRIPURA COMMUNICATION ENGINEERING(ECE)) -

The Hunt for Phoolan Devi

• COVER STORY THE HUNT FOR \ • .\-~ !PHOOLAN '--------I OEVI On theafternoonof31 March, when on an informer'a' rrp-Off the police surrounded Gulauli village in UP)j' Jalaun district, they thought they would finally, get the dacoit queen Phoolan Devi; but she slipped awa;}!. Nirmal Mitra visited Gulauli to report on the massive hunt, and the ~~~ .. encounte~ j.n.which most of Phoolan's gang was wiped out. ~ hoolan Devi. the dacoit PhoOian Devi had been arrested and queen. is a desperate was being brought 10 UP's capital by ~ ~\ woman loday, fun ninA for helicopter; it was later discovered to her life. The whole police be an A.pril Fool's joke. Even the news force of Unar Pradesh agencies had been taken in by this se~msP to be after her; she is every.- prank.) one's prize catcli. More than half of The manner in which Phoolan Devi her small gang has already been wiped escaped from the police on 31 March out in one encounter with the police makes an ahsolutely fascinating story. after another during this war that the typical of all that has come to be police have launched on dacoits after associated with dacoits-violence. wit. the bloody revenge that Phoolan Devi presence of mind, and that important took on the Behmai rhaJcurs (see Sun- mgredient, a sense of honour. It seems day 15 March) who had once insulted straight tiut of a Bombay film. and humiliated her. Other important Raba Mustaqim (he was a Muslim) dacoit leaders are angry':with her; by was killed on 4 March near Akbarpur this one outrage. -

La Regina Dei Banditi.Rtf

EDIZIONE SPECIALE In occasione del IV° Festival Internazionale della Letteratura Resistente Pitigliano - Elmo di Sorano, 8 - 9 - 10 settembre 2006 La Regina dei banditi uno spettacolo di Mutamenti Compagnia Laboratorio MILLELIRE STAMPA ALTERNATIVA con Sara Donzelli Direzione editoriale Marcello Baraghini regia Giorgio Zorcù drammaturgia Federico Bertozzi produzione Accademia Amiata Mutamenti Accademia Amiata Mutamenti Toscana delle Culture 58031 Arcidosso (Gr) tel. 348 4036571 [email protected] Grafica di copertina C&P Adver 3 Le pareti della casa erano spalmate di fango, il tet- to era di paglia. All’interno tre stanze affacciate su un cortiletto. Una per dormire, una per cucinare e una per le mucche. Nessuna finestra, vivevano al buio. Di rado, una scatola di latta con lo stoppino diventava una lampada; olio non ce n’era: costava troppo. A parte tre stuoie nella stanza della notte e una sulla soglia di quella delle mucche, l’unico arre- damento della casa era un tempietto votivo. Nella stagione calda dormivano all’aperto. Le mucche dormivano sempre al chiuso per paura dei ladri. E- rano poveri mallah: possedevano solo i regali del fiume. Alla piccola Phoolan piaceva l’odore della terra bagnata. Ne raccoglieva manciate e le masticava: era un sapore inebriante. Di manghi e lenticchie ne mangiavano pochi. Di giorno, durante il lavoro nei 5 campi, si nutrivano con piselli salati, di sera solo pa- tate. Mentre la veglia si alternava al sonno e il lavo- ro al poco riposo, la fame era continua. Come il re- spiro. Un giorno Phoolan fu convocata dal Pradham, uomo importante, capo di tutti i villaggi del distret- to, perché gli togliesse i pidocchi. -

Islam Councils

THE MUSLIM QUESTION IN EUROPE Peter O’Brien THE MUSLIM QUESTION IN EUROPE Political Controversies and Public Philosophies TEMPLE UNIVERSITY PRESS Philadelphia • Rome • Tokyo TEMPLE UNIVERSITY PRESS Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19122 www.temple.edu/tempress Copyright © 2016 by Temple University—Of Th e Commonwealth System of Higher Education All rights reserved Published 2016 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: O’Brien, Peter, 1960– author. Title: Th e Muslim question in Europe : political controversies and public philosophies / Peter O’Brien. Description: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania : Temple University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifi ers: LCCN 2015040078| ISBN 9781439912768 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781439912775 (paper : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781439912782 (e-book) Subjects: LCSH: Muslims—Europe—Politics and government. | Islam and politics—Europe. Classifi cation: LCC D1056.2.M87 O27 2016 | DDC 305.6/97094—dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015040078 Th e paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992 Printed in the United States of America 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 For Andre, Grady, Hannah, Galen, Kaela, Jake, and Gabriel Contents Acknowledgments ix 1 Introduction: Clashes within Civilization 1 2 Kulturkampf 24 3 Citizenship 65 4 Veil 104 5 Secularism 144 6 Terrorism 199 7 Conclusion: Messy Politics 241 Aft erword 245 References 249 Index 297 Acknowledgments have accumulated many debts in the gestation of this study. Arleen Harri- son superintends an able and amiable cadre of student research assistants I without whose reliable and competent support this book would not have been possible.