Studies in Indian Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Allahabad Division)-2018

List of Sixteen Lok Sabha- Members (Allahabad Division)-2018 S. Constituency/ Name of Member Permanent Address & Mobile No. Present N. Party Address & Mobile No. 1 CNB/BJP Dr. Murli Manohar Joshi 9/10-A tagore Nagar, Anukul 6, Raisina Road. New Chandra Banerjee Road, Allahabad- Delhi-110001 211002,(UP) Tel.No. (011) C/O Mr. Lalit Singh, 15/96 H Civil 23718444, 23326080 Lines, Kanpur-208001 Phone No. 0512-2399555 2 ALD/BJP Sri Shyama Charan Gupta. 44- Thornhill Road, Allahabad A-5, Gulmohar Park, .211002 (U.P) Khelgaon Road, New Ph.N0. (0532)2468585 & 86 Delhi-110049 Mob.No. 09415235305(M) Fax.N. (0532)2468579 Tels. No.(011)26532666, 26527359 3 Akbarpur Sri Devendra Singh Bhole 117/P/17 Kakadev, Kanpur (CNB/Dehat)/ Mob No.9415042234 BJP Tel. No. 0512-2500021 4 Rewa/BJP Sri Janardan Mishra Villagae & Post- Hinauta Distt.- Rewa Mob. No.-9926984118 5 Chanduli/BJP Dr. Mahendra Nath Pandey B 22/157-7, Sarswati Nagar New Maharastra Vinayaka, Distt.- Varanasi (UP) Sadan Mob. No. 09415023457 K.G. Marg, New Delhi- 110001 6 Banda/BJP Sri Bhairon Prasad Mishra Gandhiganj, Allahabad Road Karvi, Distt.-Chitrakut Mob. No.-09919020862 7 ETAH/BJP Sri Rajveer Singh A-10 Raj Palace, Mains Road, Ashok Hotel, (Raju Bhaiya) Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh Chankayank Puri New (0571) 2504040,09457011111, Delhi-110021 09756077777(M) 8 Gautam Buddha Dr. Mahesh Sharma 404 Sector- 15-A Nagar/BJP Noida-201301 (UP) Tel No.(102)- 2486666, 2444444 Mob. No.09873444255 9 Agra/BJP Dr. Ram Shankar Katheriya 1,Teachers home University Campus 43, North Avenue, Khandari, New Delhi-110001 Agra-02 (UP) Mob. -

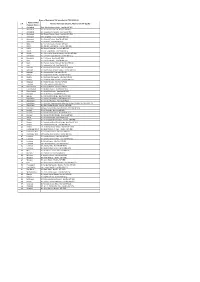

S N. Name of TAC/ Telecom District Name of Nominee [Sh./Smt./Ms

Name of Nominated TAC members for TAC (2020-22) Name of TAC/ S N. Name of Nominee [Sh./Smt./Ms] Hon’ble MP (LS/RS) Telecom District 1 Allahabad Prof. Rita Bahuguna Joshi, Hon’ble MP (LS) 2 Allahabad Smt. Keshari Devi Patel, Hon’ble MP (LS) 3 Allahabad Sh. Vinod Kumar Sonkar, Hon’ble MP (LS) 4 Allahabad Sh. Rewati Raman Singh, Hon’ble MP (RS) 5 Azamgarh Smt. Sangeeta Azad, Hon’ble MP (LS) 6 Azamgarh Sh. Akhilesh Yadav, Hon’ble MP (LS) 7 Azamgarh Sh. Rajaram, Hon’ble MP (RS) 8 Ballia Sh. Virendra Singh, Hon’ble MP (LS) 9 Ballia Sh. Sakaldeep Rajbhar, Hon’ble MP (RS) 10 Ballia Sh. Neeraj Shekhar, Hon’ble MP (RS) 11 Banda Sh. R.K. Singh Patel, Hon’ble MP (LS) 12 Banda Sh. Vishambhar Prasad Nishad, Hon’ble MP (RS) 13 Barabanki Sh. Upendra Singh Rawat, Hon’ble MP (LS) 14 Barabanki Sh. P.L. Punia, Hon’ble MP (RS) 15 Basti Sh. Harish Dwivedi, Hon’ble MP (LS) 16 Basti Sh. Praveen Kumar Nishad, Hon’ble MP (LS) 17 Basti Sh. Jagdambika Pal, Hon’ble MP (LS) 18 Behraich Sh. Ram Shiromani Verma, Hon’ble MP (LS) 19 Behraich Sh. Brijbhushan Sharan Singh, Hon’ble MP (LS) 20 Behraich Sh. Akshaibar Lal, Hon’ble MP (LS) 21 Deoria Sh. Vijay Kumar Dubey, Hon’ble MP (LS) 22 Deoria Sh. Ravindra Kushawaha, Hon’ble MP (LS) 23 Deoria Sh. Ramapati Ram Tripathi, Hon’ble MP (LS) 24 Faizabad Sh. Ritesh Pandey, Hon’ble MP (LS) 25 Faizabad Sh. Lallu Singh, Hon’ble MP (LS) 26 Farrukhabad Sh. -

Supreme Court of India Bobby Art International, Etc Vs Om Pal Singh Hoon & Ors on 1 May, 1996 Author: Bharucha Bench: Cji, S.P

Supreme Court of India Bobby Art International, Etc vs Om Pal Singh Hoon & Ors on 1 May, 1996 Author: Bharucha Bench: Cji, S.P. Bharucha, B.N. Kirpal PETITIONER: BOBBY ART INTERNATIONAL, ETC. Vs. RESPONDENT: OM PAL SINGH HOON & ORS. DATE OF JUDGMENT: 01/05/1996 BENCH: CJI, S.P. BHARUCHA , B.N. KIRPAL ACT: HEADNOTE: JUDGMENT: WITH CIVIL APPEAL NOS. 7523, 7525-27 AND 7524 (Arising out of SLP(Civil) No. 8211/96, SLP(Civil) No. 10519-21/96 (CC No. 1828-1830/96 & SLP(C) No. 9363/96) J U D G M E N T BHARUCHA, J. Special leave granted. These appeals impugn the judgment and order of a Division Bench of the High Court of Delhi in Letters Patent appeals. The Letters Patent appeals challenged the judgment and order of a learned single judge allowing a writ petition. The Letters Patent appeals were dismissed, subject to a direction to the Union of India (the second respondent). The writ petition was filed by the first respondent to quash the certificate of exhibition awarded to the film "Bandit Queen" and to restrain its exhibition in India. The film deals with the life of Phoolan Devi. It is based upon a true story. Still a child, Phoolan Devi was married off to a man old enough to be her father. She was beaten and raped by him. She was tormented by the boys of the village; and beaten by them when she foiled the advances of one of them. A village panchayat called after the incident blamed Phoolan Devi for attempting to entice the boy, who belonged to a higher caste. -

Failure of the Mahagathbandhan

ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 Failure of the Mahagathbandhan In the Lok Sabha elections of 2019 in Uttar Pradesh, the contest was keenly watched as the alliance of the Samajwadi Party, Bahujan Samaj Party, and Rashtriya Lok Dal took on the challenge against the domination of the Bharatiya Janata Party. What contributed to the continued good performance of the BJP and the inability of the alliance to assert its presence is the focus of analysis here. In the last decade, politics in Uttar Pradesh (UP) has seen radical shifts. The Lok Sabha elections 2009 saw the Congress’s comeback in UP. It gained votes in all subregions of UP and also registered a sizeable increase in vote share among all social groups. The 2012 assembly elections gave a big victory to the Samajwadi Party (SP) when it was able to get votes beyond its traditional voters: Muslims and Other Backward Classes (OBCs). The 2014 Lok Sabha elections saw the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) winning 73 seats with its ally Apna Dal. It was facilitated by the consolidation of voters cutting across caste and class, in favour of the party. Riding on the popularity of Narendra Modi, the BJP was able to trounce the regional parties and emerge victorious in the 2017 assembly elections as well. But, against the backdrop of anti-incumbency, an indifferent economic record, and with the coming together of the regional parties, it was generally believed that the BJP would not be able to replicate its success in 2019. However, the BJP’s performance in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections shows its continued domination over the politics of UP. -

List of Participating Political Parties and Abbreviations

Election Commission of India- State Election, 2008 to the Legislative Assembly Of Rajasthan LIST OF PARTICIPATING POLITICAL PARTIES PARTY TYPE ABBREVIATION PARTY NATIONAL PARTIES 1 . BJP Bharatiya Janata Party 2 . BSP Bahujan Samaj Party 3 . CPI Communist Party of India 4 . CPM Communist Party of India (Marxist) 5 . INC Indian National Congress 6 . NCP Nationalist Congress Party STATE PARTIES - OTHER STATES 7 . AIFB All India Forward Bloc 8 . CPI(ML)(L) Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) (Liberation) 9 . INLD Indian National Lok Dal 10 . JD(S) Janata Dal (Secular) 11 . JD(U) Janata Dal (United) 12 . RLD Rashtriya Lok Dal 13 . SHS Shivsena 14 . SP Samajwadi Party REGISTERED(Unrecognised) PARTIES 15 . ABCD(A) Akhil Bharatiya Congress Dal (Ambedkar) 16 . ABHM Akhil Bharat Hindu Mahasabha 17 . ASP Ambedkar Samaj Party 18 . BHBP Bharatiya Bahujan Party 19 . BJSH Bharatiya Jan Shakti 20 . BRSP Bharatiya Rashtravadi Samanta Party 21 . BRVP Bhartiya Vikas Party 22 . BVVP Buddhiviveki Vikas Party 23 . DBSP Democratic Bharatiya Samaj Party 24 . DKD Dalit Kranti Dal 25 . DND Dharam Nirpeksh Dal 26 . FCI Federal Congress of India 27 . IJP Indian Justice Party 28 . IPC Indian People¿S Congress 29 . JGP Jago Party 30 . LJP Lok Jan Shakti Party 31 . LKPT Lok Paritran 32 . LSWP Loktantrik Samajwadi Party 33 . NLHP National Lokhind Party 34 . NPSF Nationalist People's Front ASSEMBLY ELECTIONS - INDIA (Rajasthan ), 2008 LIST OF PARTICIPATING POLITICAL PARTIES PARTY TYPE ABBREVIATION PARTY REGISTERED(Unrecognised) PARTIES 35 . RDSD Rajasthan Dev Sena Dal 36 . RGD Rashtriya Garib Dal 37 . RJVP Rajasthan Vikas Party 38 . RKSP Rashtriya Krantikari Samajwadi Party 39 . RSD Rashtriya Sawarn Dal 40 . -

List of Successful Candidates

11 - LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES CONSTITUENCY WINNER PARTY Andhra Pradesh 1 Nagarkurnool Dr. Manda Jagannath INC 2 Nalgonda Gutha Sukender Reddy INC 3 Bhongir Komatireddy Raj Gopal Reddy INC 4 Warangal Rajaiah Siricilla INC 5 Mahabubabad P. Balram INC 6 Khammam Nama Nageswara Rao TDP 7 Aruku Kishore Chandra Suryanarayana INC Deo Vyricherla 8 Srikakulam Killi Krupa Rani INC 9 Vizianagaram Jhansi Lakshmi Botcha INC 10 Visakhapatnam Daggubati Purandeswari INC 11 Anakapalli Sabbam Hari INC 12 Kakinada M.M.Pallamraju INC 13 Amalapuram G.V.Harsha Kumar INC 14 Rajahmundry Aruna Kumar Vundavalli INC 15 Narsapuram Bapiraju Kanumuru INC 16 Eluru Kavuri Sambasiva Rao INC 17 Machilipatnam Konakalla Narayana Rao TDP 18 Vijayawada Lagadapati Raja Gopal INC 19 Guntur Rayapati Sambasiva Rao INC 20 Narasaraopet Modugula Venugopala Reddy TDP 21 Bapatla Panabaka Lakshmi INC 22 Ongole Magunta Srinivasulu Reddy INC 23 Nandyal S.P.Y.Reddy INC 24 Kurnool Kotla Jaya Surya Prakash Reddy INC 25 Anantapur Anantha Venkata Rami Reddy INC 26 Hindupur Kristappa Nimmala TDP 27 Kadapa Y.S. Jagan Mohan Reddy INC 28 Nellore Mekapati Rajamohan Reddy INC 29 Tirupati Chinta Mohan INC 30 Rajampet Annayyagari Sai Prathap INC 31 Chittoor Naramalli Sivaprasad TDP 32 Adilabad Rathod Ramesh TDP 33 Peddapalle Dr.G.Vivekanand INC 34 Karimnagar Ponnam Prabhakar INC 35 Nizamabad Madhu Yaskhi Goud INC 36 Zahirabad Suresh Kumar Shetkar INC 37 Medak Vijaya Shanthi .M TRS 38 Malkajgiri Sarvey Sathyanarayana INC 39 Secundrabad Anjan Kumar Yadav M INC 40 Hyderabad Asaduddin Owaisi AIMIM 41 Chelvella Jaipal Reddy Sudini INC 1 GENERAL ELECTIONS,INDIA 2009 LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATE CONSTITUENCY WINNER PARTY Andhra Pradesh 42 Mahbubnagar K. -

Uttar Pradesh Tracker Poll January 2017-Findings

Uttar Pradesh Tracker Poll January 2017-Findings Q1: Assembly elections are going to be held in Uttar Pradesh in the next few weeks. Will you vote in these elections? N (%) 1: No 239 3.7 2: Yes 6073 93.8 3: May be 107 1.7 8: Can't say 54 .8 Total 6473 100.0 Q2: The Election Commission in its verdict has allotted the cycle symbol to the Akhilesh Yadav faction, deeming it to be the real Samajwadi party. Do you believe that it was the right decision or wrong? N (%) 1: Right 3951 61.0 2: Wrong 677 10.5 8: Can't say 1846 28.5 Total 6473 100.0 Q3: If UP Assembly elections are held tomorrow, which party will you vote for? N (%) 01: Congress 204 3.1 02: BJP 1863 28.8 03: BSP 1490 23.0 05: RLD 124 1.9 06: Apna Dal 3 .0 08: Apna Dal (Anupriya Patel) 14 .2 09: Quami Ekta Dal 9 .1 11: Peace Party 54 .8 12: Mahan Dal 20 .3 13: CPI 66 1.0 14: CPI(M) 16 .3 17: RJD 5 .1 Lokniti-Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, CSDS Page 1 Uttar Pradesh Tracker Poll January 2017-Findings N (%) 19: Shiv Sena 18 .3 21: AIMIM 25 .4 22: INLD 55 .8 23: LJP 13 .2 26: Lok Dal 17 .3 32: SP (Akhilesh Yadav)/SP 1972 30.5 56: SP (Mulayam Singh) 84 1.3 96: Independent 41 .6 97: Other parties 313 4.8 98: Can’t say/Did not tell 65 1.0 Total 6473 100.0 a: (If voted in Q3 ) On the day of voting will you vote for the same party which you voted now or your decision may change? N (%) Valid (%) Valid 1: Vote for the same party 4459 68.9 73.9 2: May change 800 12.4 13.3 8: Don't know 773 11.9 12.8 Total 6033 93.2 100.0 Missing 9: N.A. -

Western Uttar Pradesh: Caste Arithmetic Vs Nationalism

VERDICT 2019 Western Uttar Pradesh: Caste Arithmetic vs Nationalism SMITA GUPTA Samajwadi Party patron Mulayam Singh Yadav exchanges greetings with Bahujan Samaj Party supremo Mayawati during their joint election campaign rally in Mainpuri, on April 19, 2019. Photo: PTI In most of the 26 constituencies that went to the polls in the first three phases of the ongoing Lok Sabha elections in western Uttar Pradesh, it was a straight fight between the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) that currently holds all but three of the seats, and the opposition alliance of the Samajwadi Party, the Bahujan Samaj Party and the Rashtriya Lok Dal. The latter represents a formidable social combination of Yadavs, Dalits, Muslims and Jats. The sort of religious polarisation visible during the general elections of 2014 had receded, Smita Gupta, Senior Fellow, The Hindu Centre for Politics and Public Policy, New Delhi, discovered as she travelled through the region earlier this month, and bread and butter issues had surfaced—rural distress, delayed sugarcane dues, the loss of jobs and closure of small businesses following demonetisation, and the faulty implementation of the Goods and Services Tax (GST). The Modi wave had clearly vanished: however, BJP functionaries, while agreeing with this analysis, maintained that their party would have been out of the picture totally had Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his message of nationalism not been there. travelled through the western districts of Uttar Pradesh earlier this month, conversations, whether at district courts, mofussil tea stalls or village I chaupals1, all centred round the coming together of the Samajwadi Party (SP), the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) and the Rashtriya Lok Dal (RLD). -

Visitor Analytics Report

PMINDIA website (pmindia.gov.in) Visitor Analytics Report 30th April, 2016 – 13th May, 2016 The new website of PM India was launched on May 26, 2015. This report, highlighting the visitor analytics data of the website, has been prepared for submission to the Prime Minister’s Office by the National Informatics Centre (NIC). The purpose of this report is to understand the usage pattern of the website’s visitors as an input for the continual improvement of the website. Prepared by: National Informatics Centre May 13, 2016 pmindia.gov.in: Visitor Analytics Report 30 Apr to 13 May, 2016 Executive Summary • The total number of sessions for this time period are 1,58,785. • The average visit duration for this time period is 2 minute 05 seconds. • The website is being accessed across all three types of devices (Desktop/laptop, mobile and tablet); however, desktop was the most popular device used for visiting the website. • The most popular news update: 1. PM launches Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana at Ballia; 5 crore beneficiaries to be provided cooking gas connections • The most popular speech: 1. Simhasth Kumbh Mahaparv 2016: Some Glimpses • The most popular image: The Chief Minister of U.P, Shri Akhilesh Yadav meets the Prime Minister, Shri Narendra Modi to discuss drought situation, in New Delhi on May 07, 2016. Prepared by: National Informatics Centre May 13, 2016 pmindia.gov.in: Visitor Analytics Report 30 Apr to 13 May, 2016 Statistics at a glance 1,58,785 1,23,822 Total visits Number of unique visitors 20 May 06th Maximum pages Highest number -

“Low” Caste Women in India

Open Cultural Studies 2018; 2: 735-745 Research Article Jyoti Atwal* Embodiment of Untouchability: Cinematic Representations of the “Low” Caste Women in India https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2018-0066 Received May 3, 2018; accepted December 7, 2018 Abstract: Ironically, feudal relations and embedded caste based gender exploitation remained intact in a free and democratic India in the post-1947 period. I argue that subaltern is not a static category in India. This article takes up three different kinds of genre/representations of “low” caste women in Indian cinema to underline the significance of evolving new methodologies to understand Black (“low” caste) feminism in India. In terms of national significance, Acchyut Kanya represents the ambitious liberal reformist State that saw its culmination in the constitution of India where inclusion and equality were promised to all. The movie Ankur represents the failure of the state to live up to the postcolonial promise of equality and development for all. The third movie, Bandit Queen represents feminine anger of the violated body of a “low” caste woman in rural India. From a dacoit, Phoolan transforms into a constitutionalist to speak about social justice. This indicates faith in Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s India and in the struggle for legal rights rather than armed insurrection. The main challenge of writing “low” caste women’s histories is that in the Indian feminist circles, the discourse slides into salvaging the pain rather than exploring and studying anger. Keywords: Indian cinema, “low” caste feminism, Bandit Queen, Black feminism By the late nineteenth century due to certain legal and socio-religious reforms,1 space of the Indian family had been opened to public scrutiny. -

October 2016 Dossier

INDIA AND SOUTH ASIA: OCTOBER 2016 DOSSIER The October 2016 Dossier highlights a range of domestic and foreign policy developments in India as well as in the wider region. These include analyses of the ongoing confrontation between India and Pakistan, the measures by the government against black money and terrorism as well as the scenarios in India's mega-state Uttar Pradesh on the eve of crucial state elections in 2017, the 17th India-Russia Annual Summit and the Eighth BRICS Summit. Dr Klaus Julian Voll FEPS Advisor on Asia With Dr. Joyce Lobo FEPS STUDIES OCTOBER 2016 Part I India - Domestic developments • Confrontation between India and Pakistan • Modi: Struggle against black money + terrorism • Uttar Pradesh: On the eve of crucial elections • Pollution: Delhi is a veritable gas-chamber Part II India - Foreign Policy Developments • 17th India-Russia Annual Summit • Eighth BRICS Summit Part III South Asia • Outreach Summit of BRICS Leaders with the Leaders of BIMSTEC 2 Part I India - Domestic developments Dr. Klaus Voll analyses the confrontation between India and Pakistan, the measures by the government against black money and terrorism as well as the scenarios in India's mega-state Uttar Pradesh on the eve of crucial state elections in 2017 and the extreme pollution crisis in Delhi, the National Capital ReGion and northern India. Modi: Struggle against black money + terrorism: 500 and 1000-Rupee notes invalidated Prime Minister Narendra Modi addressed on the 8th of November 2016 the nation in Hindi and EnGlish. Before he had spoken to President Pranab Mukherjee and the chiefs of the army, navy and air force. -

On Easter, Violence Resurrects in Lanka

Follow us on: facebook.com/dailypioneer RNI No.2016/1957, REGD NO. SSP/LW/NP-34/2019-21 @TheDailyPioneer instagram.com/dailypioneer/ Established 1864 OPINION 8 WORLD 12 SPORT 15 Published From GOODBYE JET SUDAN PROTEST LEADERS TO EVERTON BEAT DELHI LUCKNOW BHOPAL BHUBANESWAR RANCHI RAIPUR CHANDIGARH AIRWAYS? UNVEIL CIVILIAN RULING BODY MANCHESTER UNITED 4-0 DEHRADUN HYDERABAD VIJAYWADA Late City Vol. 155 Issue 108 LUCKNOW, MONDAY APRIL 22, 2019; PAGES 16 `3 *Air Surcharge Extra if Applicable FIRST FILM IS SPECIAL: AYUSHMANN} } 14 VIVACITY www.dailypioneer.com On Easter, violence resurrects in Lanka 215 killed in 8 blasts; 3 Indians, 30 other foreigners among dead PTI n NEW DELHI Modi condemns string of eight devastating Ablasts, including suicide attacks, struck churches and attack, offers help; luxury hotels frequented by for- eigners in Sri Lanka on Easter Sunday, killing 215 people, including three Indians and an Sushma in touch American, and shattering a decade of peace in the island PNS n NEW DELHI Their names are Lakshmi, nation since the end of the bru- Narayan Chandrashekhar and tal civil war with the LTTE. ondemning the “cold- Ramesh, Sushma said adding The blasts — one of the Cblooded and pre-planned details are being ascertained. deadliest attacks in the coun- barbaric acts” in Sri Lanka, Sushma tweeted, “I con- try’s history — targeted St Prime Minister Narendra veyed to the Foreign Minister Anthony’s Church in Colombo, Modi spoke to Sri Lankan of Sri Lanka that India is St Sebastian’s Church in the President Maithripala Sirisena ready to provide all humani- western coastal town of and Prime Minister Ranil tarian assistance.