The Fire in the Firefly: the Unspoken (Speaks)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Disney Visual Media Influences Children's Perceptions of Family a Content Analysis an Honors Thesis

Family on Film: How Disney Visual Media Influences Children's Perceptions of Family A Content Analysis An Honors Thesis (SOC 424) by Alexandra Garman Thesis Advisor Dr. Richard Petts ) c' __ / Ball State University Muncie, Indiana December, 2011 Expected Date of Graduation December 17, 2011 ," I . / ' 1 Abstract The Walt Disney Company has held a decades-long grip on family entertainment through visual media, amusement parks, clothing, toys, and even food. American children, and children throughout the world, are readily exposed to Disney's visual media as often as several times a day through film and television shows. As such, reviewing what this media says and analyzing its potential affects on our society can be beneficial in determining what messages children are receiving regarding values and norms concerning family. Specifically, analyzing family structure can help to provide an outlook for future normative structure. Depicted family interactions may also reflect how realistic families interact, what children expect from their families, and how children may interact with their own families in coming years. This study seeks to analyze various media released in recent years (2006-2011) and how these media portray family structure and interaction. Family appears to be variant in structure, including varied parental figures, as well as occasionally including non-biological figures. However, the family structure still seems, on the whole, to fit or otherwise promote (through inability of variants to do well) the traditional family model ofheterosexual, married biological parents and their offspring. Interestingly, Disney appears to place a great emphasis on fathers. Interactions between family members are relatively balanced, with some families being more positive in interaction and others being more negative. -

A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works Krista Silva University of Puget Sound, [email protected]

Student Research and Creative Works Book Collecting Contest Essays University of Puget Sound Year 2015 The Wonderful World of Whedon: A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works Krista Silva University of Puget Sound, [email protected] This paper is posted at Sound Ideas. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/book collecting essays/6 Krista Silva The Wonderful World of Whedon: A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works I am an inhabitant of the Whedonverse. When I say this, I don’t just mean that I am a fan of Joss Whedon. I am sincere. I live and breathe his works, the ever-expanding universe— sometimes funny, sometimes scary, and often heartbreaking—that he has created. A multi- talented writer, director and creator, Joss is responsible for television series such as Buffy the Vampire Slayer , Firefly , Angel , and Dollhouse . In 2012 he collaborated with Drew Goddard, writer for Buffy and Angel , to bring us the satirical horror film The Cabin in the Woods . Most recently he has been integrated into the Marvel cinematic universe as the director of The Avengers franchise, as well as earning a creative credit for Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. My love for Joss Whedon began in 1998. I was only eleven years old, and through an incredible moment of happenstance, and a bit of boredom, I turned the television channel to the WB and encountered my first episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer . I was instantly smitten with Buffy Summers. She defied the rules and regulations of my conservative southern upbringing. -

The Citizens Homeland Defense Guide II.Gas Masks, Anthrax And

free stuff Find old friends Get a date Free downloads Webmaster$$$ ANTI-TERRORISM CLASS FREE INFO! FREE CREDIT REPORT -BEAT CYBER CRIME (RECOMMENDED ) (RECOMMEND) Webmasters your welcome to upload this guide on your site Back to table contents Join our Mailing list to get new updated ebooks Citizens Defense Guide 2 Table of contents: 1. Foreword 2. VOLUNTEER (HELP FIGHT TERRORISM) 3. Recommend books&videos to view 4. Household checklist 5. Hand to Hand combat 6. How to survive a hijacking 7. The world of terrorisms 8. Biological terrorisms 9. Chemical terrorisms 10. Nuclear terrorisms 11. Cyber terrorisms 12. Preparedness 13. Anthrax links 14. First aid 15. End time prophecy 16. News, military, and info sites 17. Quick Reports 18. Survival store 19. Survival tips 20. Survival links 21. Internet opportunities $ 22. Free stuff 23. Disclaimer 24. Sponsors Before you read this ebook learn these definitions: Survive - to remain alive or in existence after; to continue living or existing. Survivalist - one who takes measures, as storing food and weapons, to ensure survival after economic collapse, nuclear war, etc. Survivor - 1. one that survives 2.someone capable of surviving changing conditions, misfortune, etc. Prepare - 1. to make ready 2. to equip or furnish 3. to put together 4. to make things ready 5. to make oneself ready Preparedness - the state of being prepared, especially for waging war. Disaster - any happening that causes great harm or damage; calamity. Emergency - a sudden, generally unexpected occurrence demanding immediate action. Citizens Defense Guide 2 Back to table contents Join our Mailing list to get new updated ebooks Issue 2: Foreword If you like this ebook you can send $5. -

Molecular Systematics of the Firefly Genus Luciola

animals Article Molecular Systematics of the Firefly Genus Luciola (Coleoptera: Lampyridae: Luciolinae) with the Description of a New Species from Singapore Wan F. A. Jusoh 1,* , Lesley Ballantyne 2, Su Hooi Chan 3, Tuan Wah Wong 4, Darren Yeo 5, B. Nada 6 and Kin Onn Chan 1,* 1 Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum, National University of Singapore, Singapore 117377, Singapore 2 School of Agricultural and Wine Sciences, Charles Sturt University, Wagga Wagga 2678, Australia; [email protected] 3 Central Nature Reserve, National Parks Board, Singapore 573858, Singapore; [email protected] 4 National Parks Board HQ (Raffles Building), Singapore Botanic Gardens, Singapore 259569, Singapore; [email protected] 5 Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore, Singapore 117543, Singapore; [email protected] 6 Forest Biodiversity Division, Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong 52109, Malaysia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (W.F.A.J.); [email protected] (K.O.C.) Simple Summary: Fireflies have a scattered distribution in Singapore but are not as uncommon as many would generally assume. A nationwide survey of fireflies in 2009 across Singapore documented 11 species, including “Luciola sp. 2”, which is particularly noteworthy because the specimens were collected from a freshwater swamp forest in the central catchment area of Singapore and did not fit Citation: Jusoh, W.F.A.; Ballantyne, the descriptions of any known Luciola species. Ten years later, we revisited the same locality to collect L.; Chan, S.H.; Wong, T.W.; Yeo, D.; new specimens and genetic material of Luciola sp. 2. Subsequently, the mitochondrial genome of that Nada, B.; Chan, K.O. -

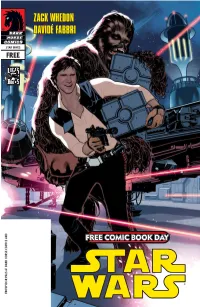

Zack Whedon Davidé Fabbri Zack Whedon 2/17/12 1:11 Pm ® S R

ZACKZACK WHEDONWHEDON ® DAVIDÉDAVIDÉ FABBRIFABBRI STAR WARS FREE ® FROM YOUR PALS AT DARK HORSE COMICS AND COMICS HORSE DARK AT PALS YOUR FROM FCBD12 SW-SEREN.indd 1 2/17/12 1:11 PM FCBD12 SW-SEREN.indd 2 tions, or locales, without satiric intent, is coincidental. Printed by Cadmus Communications, Easton, PA, U.S.A. tions, orlocales,without satiricintent,iscoincidental.Printed byCadmusCommunications,Easton, PA, Anyresemblancetoactual persons(livingordead),events,institu either aretheproduct oftheauthor’simaginationorareused fictitiously. writtenpermissionofDarkHorse Comics,Inc.Names,characters,places,andincidentsfeaturedinthispublication without theexpress categories andcountries.Allrightsreserved. Noportionofthispublicationmaybereproducedortransmitted,inanyform or are ©2012LucasfilmLtd.DarkHorse Comics® andtheDarkHorselogoaretrademarksofComics,Inc.,registered inva Wars andillustrationsforStar Text ©2012LucasfilmLtd.&™.Allrightsreserved.Usedunderauthorization. Milwaukie, OR97222.StarWars ArtoftheBadDeal,”May2012.PublishedbyDarkHorseComics, Inc.,10956SEMainStreet, WARS—“The STAR FREE COMICBOOK DAY: RONDA D MICHAEL A D ZACK WHEDON ZACK advertising sales: (503) 905-2370 » comic shop locator service: (888)266-4226 service: (503)905-2370»comicshop locator sales: advertising ALLA ALLA DA AVIDÉ FABBRI AVIDÉ MIKE RANDY RANDY M H M C assistant editor assistant collection editor P F HRISTIAN REDD cover art SIERRA R lettering V T ATTISON T ICHARDSON INA ALESSI ECCHIA talk about this issue online at: online at: aboutthisissue talk Pencils HO UGHES Colors STRADLE publisher D script designer YE YE AVID M editor Inks HAHN LINS AS Y STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS ANDERMAN at lucas licensing. ANDERMAN at ALDERS, CAROL special thankstoJ ROEDER Comics! Horse Dark from pals this your at free offering enjoy please afirst-timer, or time reader along you’re whether But Emperor. -

The AUSS Firefly: a Distributed Sensing and Coordination Platform for First-Year Engineering Education

The AUSS FIREfly: A Distributed Sensing and Coordination Platform for First-Year Engineering Education Derrick Yeo1 , Derek A. Paley2 Department of Aerospace Engineering, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland , 20742, U.S.A This paper describes an embedded computing and sensing system developed to serve the needs of the Autonomous Unmanned Systems Stream (AUSS), a two-semester sequence at the University of Maryland that provides first-year students with an inquiry-based introduction to concepts in engineering and autonomy. AUSS is part of the UMD First-year Innovation and Research Experience program (FIRE), a campus-wide initiative that provides course-based undergraduate research experiences for first-year students. FIRE aims to propel students towards planning, conducting and reporting research that is relevant to the scientific community. To serve its educational mission, the AUSS needs to equip incoming freshmen with the necessary technical capabilities to pursue engineering research in autonomous systems. The AUSS FIREfly is a robotics kit designed to be a training tool and a research platform. Each device is assembled and programmed by an individual student, exposing the builder to topics such as circuit design, information theory, and computer science. Once completed, the FIREfly uses onboard infrared transceivers to emulate the photic system of a firefly, supporting group-led experiments in multi-agent synchronization. The devices are also designed to serve as nodes in a distributed sensor network when equipped with additional measurement modules such as airspeed probes. This paper presents the design features of the AUSS FIREfly system within the context of the challenges faced by a first-year research education experience. -

Travel-Guide-Oaxaca.Pdf

IHOW TO USE THIS BROCHURE Tap this to move to any topic in the Guide. Tap this to go to the Table of Contents or the related map. Índex Map Tap any logo or ad space for immediate access to Make a reservation by clicking here. more information. RESERVATION Déjanos mostrarte los colores y la magia de Oaxaca Con una ubicación estratégica que te permitirá disfrutar los puntos de interés más importantes de Oaxaca y con un servicio que te hará vivir todo el arte de la hospitalidad, el Hotel Misión Oaxaca es el lugar ideal para el viaje de placer y los eventos sociales. hotelesmision.com Tap any number on the maps and go to the website Subscribe to DESTINATIONS MEXICO PROGRAM of the hotel, travel agent. and enjoy all its benefits. 1 SUBSCRIPTION FORM Weather conditions and weather forecast Walk along the site with Street View Enjoy the best vídeos and potos. Come and join us on social media! Find out about our news, special offers, and more. Plan a trip using in-depth tourist attraction information, find the best places to visit, and ideas for an unforgettable travel experience. Be sure to follow us Index 1. Oaxaca. Art & Color. 24. Route to Mitla. 2. Discovering Oaxaca. Tour 1. 25. Route to Mitla. 3. Discovering Oaxaca. Tour 1. Hotel Oaxaca Real. 26. Route to Mitla. Map of Mitla. AMEVH. 4. Discovering Oaxaca. Tour 1. 27. Route to Monte Albán - Zaachila. Oro de Monte Albán (Jewelry). 28. Route to Monte Albán - Zaachila. 5. Discovering Oaxaca. Tour 1. Map of Monte Albán. -

Radio Science Bulletin Staff

INTERNATIONAL UNION UNION OF RADIO-SCIENTIFIQUE RADIO SCIENCE INTERNATIONALE ISSN 1024-4530 Bulletin Vol. 2017, No. 363 December 2017 Radio Science URSI, c/o Ghent University (INTEC) St.-Pietersnieuwstraat 41, B-9000 Gent (Belgium) Contents Radio Science Bulletin Staff ....................................................................................... 3 URSI Offi cers and Secretariat.................................................................................... 6 Editor’s Comments ..................................................................................................... 8 On Low-Pass, High-Pass, Bandpass, and Stop-Band NGD RF Passive Circuits 10 Recent Developments in Distributed Negative-Group-Delay Circuits .................28 A Zero-Order-Closure Turbulent Flux-Conservation Technique for Blending Refractivity Profi les in the Marine Atmospheric Boundary layer ................... 39 Conformal Antennas for Miniature In-Body Devices: The Quest to Improve Radiation Performance ........................................................................................ 52 In Memoriam: Jean Van Bladel ............................................................................... 65 In Memoriam: Karl Rawer ...................................................................................... 66 In Memoriam: Thomas J. (Tom) Brazil .................................................................. 68 Et Cetera .................................................................................................................... 70 -

Bruce Walker Musical Theater Recording Collection

Bruce Walker Musical Theater Recording Collection Bruce Walker Musical Theater Recording Collection Recordings are on vinyl unless marked otherwise marked (* = Cassette or # = Compact Disc) KEY OC - Original Cast TV - Television Soundtrack OBC - Original Broadway Cast ST - Film Soundtrack OLC - Original London Cast SC - Studio Cast RC - Revival Cast ## 2 (OC) 3 GUYS NAKED FROM THE WAIST DOWN (OC) 4 TO THE BAR 13 DAUGHTERS 20'S AND ALL THAT JAZZ, THE 40 YEARS ON (OC) 42ND STREET (OC) 70, GIRLS, 70 (OC) 81 PROOF 110 IN THE SHADE (OC) 1776 (OC) A A5678 - A MUSICAL FABLE ABSENT-MINDED DRAGON, THE ACE OF CLUBS (SEE NOEL COWARD) ACROSS AMERICA ACT, THE (OC) ADVENTURES OF BARON MUNCHHAUSEN, THE ADVENTURES OF COLORED MAN ADVENTURES OF MARCO POLO (TV) AFTER THE BALL (OLC) AIDA AIN'T MISBEHAVIN' (OC) AIN'T SUPPOSED TO DIE A NATURAL DEATH ALADD/THE DRAGON (BAG-A-TALE) Bruce Walker Musical Theater Recording Collection ALADDIN (OLC) ALADDIN (OC Wilson) ALI BABBA & THE FORTY THIEVES ALICE IN WONDERLAND (JANE POWELL) ALICE IN WONDERLAND (ANN STEPHENS) ALIVE AND WELL (EARL ROBINSON) ALLADIN AND HIS WONDERFUL LAMP ALL ABOUT LIFE ALL AMERICAN (OC) ALL FACES WEST (10") THE ALL NIGHT STRUT! ALICE THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS (TV) ALL IN LOVE (OC) ALLEGRO (0C) THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN AMBASSADOR AMERICAN HEROES AN AMERICAN POEM AMERICANS OR LAST TANGO IN HUAHUATENANGO .....................(SF MIME TROUPE) (See FACTWINO) AMY THE ANASTASIA AFFAIRE (CD) AND SO TO BED (SEE VIVIAN ELLIS) AND THE WORLD GOES 'ROUND (CD) AND THEN WE WROTE... (FLANDERS & SWANN) AMERICAN -

Holding out for a Hero(Ine): an Examination of the Presentation and Treatment of Female Superheroes in Marvel Movies Robyn Joffe

Holding Out for a Hero(ine): An Examination of the Presentation and Treatment of Female Superheroes in Marvel Movies Robyn Joffe Abstract Prior to the release of Ant-Man and the Wasp (2018) and Captain Marvel (2019), the way that female characters from the Marvel Comics’ canon were realized onscreen was problematic for several reasons and encumbered by issues rooted in the strong female character trope and its postfeminist origins. A close examination of three Marvel superheroines—Black Widow, Scarlet Witch, and Mystique—reveals that while they initially appear to be positioned as equal to their male teammates, they are consistently burdened with difficulties and challenges that men never have to face. The filmmakers’ focus on these women’s appearance and sex appeal, their double standard for violent women, and their perception of a woman’s role, create a picture of “strong” women that is questionable at best and damaging at worst. Keywords: Marvel, postfeminism, sexualization, infantilization, maternalism Introduction The Marvel Cinematic Universe is a media franchise and shared universe, owned by Marvel Studios and currently consists of twenty feature films, seven television series, one digital series, assorted direct-to-video short films, tie-in comic books, and other mixed media products. It is a shared universe that is actively expanding as more and more properties are slated for release. The X-Men film series, until recently owned by 20th Century Fox, is one of the interconnecting series of films based on specific characters from Marvel Comics. It currently consists of eleven films and two television series, with more to be released this year. -

Working Paper Series

Working Paper Series SPECIAL ISSUE: REVISITING AUDIENCES: RECEPTION, IDENTITY, TECHNOLOGY Superheroes and Shared Universes: How Fans and Auteurs Are Transforming the Hollywood Blockbuster Edmund Smith University of Otago Abstract: Over the course of the 2000s, the Hollywood blockbuster welcomed the superhero genre into its ranks after these films saw an explosion in popularity. Now, the ability to produce superhero films through an extended transmedia franchise is a coveted prize for major studios. The likes of Sony, 20th Century Fox, and Warner Bros. are locked in competition with the new kid on the block, Marvel, who changed the way Hollywood produces the blockbuster franchise. Drawing upon my previous and current postgraduate work, this essay will discuss fans and authorship in relation to the superhero genre which, I posit, exemplifies the industrial model of the Hollywood blockbuster and the cycle of appropriation and revitalisation that defines it. I will explain how studios like Marvel call upon up-and-coming directorial talent to further legitimise their films in order to appeal to middlebrow expectations through auteur credibility. Such director selection demonstrates: 1) how the contemporary auteur has become commodified within transmedia franchise blockbusters and, 2) how, due to the conflicting creative and commercial interests inherent to the blockbuster, these films are now supported by a form of co-dependent authorship. Related to this, I will also explore how fans function within this industrial context and the effect that their fannish support and promotion of superhero films has had on the latter’s viability as a staple of studio production. ISSN2253-4423 © MFCO Working Paper Series 3 MFCO Working Paper Series 2017 Introduction From the 2000s, through to the present day, the superhero film has seen a titanic increase in popularity, becoming a staple of the mainstream film industry. -

Preaching to the Converted: Making Responsible Evangelical Subjects Through Media by Holly Thomas a Thesis Submitted to the Facu

Preaching to the Converted: Making Responsible Evangelical Subjects Through Media By Holly Thomas A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2016, Holly Thomas Abstract This dissertation examines contemporary televangelist discourses in order to better articulate prevailing models of what constitutes ideal-type evangelical subjectivities and televangelist participation in an increasingly mediated religious landscape. My interest lies in apocalyptic belief systems that engage end time scenarios to inform understandings of salvation. Using a Foucauldian inspired theoretical-methodology shaped by discourse analysis, archaeology, and genealogy, I examine three popular American evangelists who represent a diverse array of programming content: Pat Robertson of the 700 Club, John Hagee of John Hagee Today, and Jack and Rexella Van Impe of Jack Van Impe Presents. I argue that contemporary evangelical media packages now cut across a variety of traditional and new technologies to create a seamless mediated empire of participatory salvation where believers have access to complementary evangelist products and messages twenty-four hours a day from a multitude of access points. For these reasons, I now refer to televangelism as mediated evangelism and televangelists as mediated evangelists while acknowledging that the televised programs still form the cornerstone of their mediated messages and engagement with believers. The discursive formations that take shape through this landscape of mediated evangelism contribute to an apocalyptically informed religious-political subjectivity that identifies civic and political engagement as an expected active choice and responsibility for attaining salvation, in line with other more obviously evangelical religious practices, like prayer, repentance, and acceptance of Jesus Christ as savior.