Working Paper Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Flying Model Rocket Catalog

Flying Model Rocket Catalog TM TABLE OF CONTENTS Model Rocket Basics . 5 Fly Big with Advanced Rockets/Pro Series II . 66 Get Started with Launch Sets . 10 Model Rocket Engine Performance Chart . 70 Easy to Build Beginner Rockets . 16 Engine Time/Thrust Curves . 72-73 Challenge Yourself a Little More! . 22 Building Supplies . 84 Payload Rockets . 30 Altitude Tracking . 82 Multi-Stage Rockets . 34 Estes Education . 86 Fun Recovery Rockets . 40 Bulk Packs for Education . 88 Designer Signature Series . 45 Lifetime Launch System . 94 Imagine New Worlds with Space Voyagers . 46 Phantom Classroom Demonstrator Rocket . 96 Destination Mars™ Rockets . 50 Rocket Science Starter Set . 98 Space Corps™ Rockets . 54 Model Rocket Safety Code . 100 Scale Model Rockets . 58 Index . 102 Welcome to the exciting world of model rocketry. now this rocket science! here is no thrill quite like launching a model rocket you have built, watching it streak skyward, reach apogee (peak altitude), then gently Treturn to earth on its parachute. In a very real sense, model rocketeers experience the same excitement felt by America’s space scientists and astronauts as they push humankind’s horizons relentlessly forward to the stars. The best way to get started is with an Estes® launch set or starter set (see pages 10-15). Each launch set has nearly everything you need to build and fly your first rocket. Estes Industries, LLC encourages membership As you increase your rocketry skills, you can progress to new and exciting in the National Association projects including multi-stage rockets, payload experiments and scale models. of Rocketry for the active Whether you are a hobby beginner or expert, Estes Industries will help you model rocketry enthusiast. -

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

How Disney Visual Media Influences Children's Perceptions of Family a Content Analysis an Honors Thesis

Family on Film: How Disney Visual Media Influences Children's Perceptions of Family A Content Analysis An Honors Thesis (SOC 424) by Alexandra Garman Thesis Advisor Dr. Richard Petts ) c' __ / Ball State University Muncie, Indiana December, 2011 Expected Date of Graduation December 17, 2011 ," I . / ' 1 Abstract The Walt Disney Company has held a decades-long grip on family entertainment through visual media, amusement parks, clothing, toys, and even food. American children, and children throughout the world, are readily exposed to Disney's visual media as often as several times a day through film and television shows. As such, reviewing what this media says and analyzing its potential affects on our society can be beneficial in determining what messages children are receiving regarding values and norms concerning family. Specifically, analyzing family structure can help to provide an outlook for future normative structure. Depicted family interactions may also reflect how realistic families interact, what children expect from their families, and how children may interact with their own families in coming years. This study seeks to analyze various media released in recent years (2006-2011) and how these media portray family structure and interaction. Family appears to be variant in structure, including varied parental figures, as well as occasionally including non-biological figures. However, the family structure still seems, on the whole, to fit or otherwise promote (through inability of variants to do well) the traditional family model ofheterosexual, married biological parents and their offspring. Interestingly, Disney appears to place a great emphasis on fathers. Interactions between family members are relatively balanced, with some families being more positive in interaction and others being more negative. -

2012 Sundance Film Festival Announces Awards

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contacts: January 28, 2012 Casey De La Rosa 310.360.1981 [email protected] 2012 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES AWARDS The House I Live In, Beasts of the Southern Wild, The Law in These Parts and Violeta Went to Heaven Earn Grand Jury Prizes Audience Favorites Include The Invisible War, The Surrogate, SEARCHING FOR SUGAR MAN and Valley of Saints Sleepwalk With Me Receives Best of NEXT <=> Audience Award Park City, UT — Sundance Institute this evening announced the Jury, Audience, NEXT <=> and other special awards of the 2012 Sundance Film Festival at the Festival‘s Awards Ceremony, hosted by Parker Posey in Park City, Utah. An archived video of the ceremony in its entirety is available at www.sundance.org/live. ―Every year the Sundance Film Festival brings to light exciting new directions and fresh voices in independent film, and this year is no different,‖ said John Cooper, Director of the Sundance Film Festival. ―While these awards further distinguish those that have had the most impact on audiences and our jury, the level of talent showcased across the board at the Festival was really impressive, and all are to be congratulated and thanked for sharing their work with us.‖ Keri Putnam, Executive Director of Sundance Institute, said, ―As we close what was a remarkable 10 days of the 2012 Sundance Film Festival, we look to the year ahead with incredible optimism for the independent film community. As filmmakers continue to push each other to achieve new heights in storytelling we are excited to see what‘s next.‖ The 2012 Sundance Film Festival Awards presented this evening were: The Grand Jury Prize: Documentary was presented by Charles Ferguson to: The House I Live In / U.S.A. -

A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works Krista Silva University of Puget Sound, [email protected]

Student Research and Creative Works Book Collecting Contest Essays University of Puget Sound Year 2015 The Wonderful World of Whedon: A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works Krista Silva University of Puget Sound, [email protected] This paper is posted at Sound Ideas. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/book collecting essays/6 Krista Silva The Wonderful World of Whedon: A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works I am an inhabitant of the Whedonverse. When I say this, I don’t just mean that I am a fan of Joss Whedon. I am sincere. I live and breathe his works, the ever-expanding universe— sometimes funny, sometimes scary, and often heartbreaking—that he has created. A multi- talented writer, director and creator, Joss is responsible for television series such as Buffy the Vampire Slayer , Firefly , Angel , and Dollhouse . In 2012 he collaborated with Drew Goddard, writer for Buffy and Angel , to bring us the satirical horror film The Cabin in the Woods . Most recently he has been integrated into the Marvel cinematic universe as the director of The Avengers franchise, as well as earning a creative credit for Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. My love for Joss Whedon began in 1998. I was only eleven years old, and through an incredible moment of happenstance, and a bit of boredom, I turned the television channel to the WB and encountered my first episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer . I was instantly smitten with Buffy Summers. She defied the rules and regulations of my conservative southern upbringing. -

A Chilling Look Back at Jeph Loeb and Tim Sale's

Jeph Loeb Sale and Tim at A back chilling look Batman and Scarecrow TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. 0 9 No.60 Oct. 201 2 $ 8 . 9 5 1 82658 27762 8 COMiCs HALLOWEEN HEROES AND VILLAINS: • SOLOMON GRUNDY • MAN-WOLF • LORD PUMPKIN • and RUTLAND, VERMONT’s Halloween Parade , bROnzE AGE AnD bEYOnD ’ s SCARECROW i . Volume 1, Number 60 October 2012 Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! The Retro Comics Experience! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich J. Fowlks COVER ARTIST Tim Sale COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS Scott Andrews Tony Isabella Frank Balkin David Anthony Kraft Mike W. Barr Josh Kushins BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . .2 Bat-Blog Aaron Lopresti FLASHBACK: Looking Back at Batman: The Long Halloween . .3 Al Bradford Robert Menzies Tim Sale and Greg Wright recall working with Jeph Loeb on this landmark series Jarrod Buttery Dennis O’Neil INTERVIEW: It’s a Matter of Color: with Gregory Wright . .14 Dewey Cassell James Robinson The celebrated color artist (and writer and editor) discusses his interpretations of Tim Sale’s art Nicholas Connor Jerry Robinson Estate Gerry Conway Patrick Robinson BRING ON THE BAD GUYS: The Scarecrow . .19 Bob Cosgrove Rootology The history of one of Batman’s oldest foes, with comments from Barr, Davis, Friedrich, Grant, Jonathan Crane Brian Sagar and O’Neil, plus Golden Age great Jerry Robinson in one of his last interviews Dan Danko Tim Sale FLASHBACK: Marvel Comics’ Scarecrow . .31 Alan Davis Bill Schelly Yep, there was another Scarecrow in comics—an anti-hero with a patchy career at Marvel DC Comics John Schwirian PRINCE STREET NEWS: A Visit to the (Great) Pumpkin Patch . -

Sofia Coppola and the Significance of an Appealing Aesthetic

SOFIA COPPOLA AND THE SIGNIFICANCE OF AN APPEALING AESTHETIC by LEILA OZERAN A THESIS Presented to the Department of Cinema Studies and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts June 2016 An Abstract of the Thesis of Leila Ozeran for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of Cinema Studies to be taken June 2016 Title: Sofia Coppola and the Significance of an Appealing Aesthetic Approved: r--~ ~ Professor Priscilla Pena Ovalle This thesis grew out of an interest in the films of female directors, producers, and writers and the substantially lower opportunities for such filmmakers in Hollywood and Independent film. The particular look and atmosphere which Sofia Coppola is able to compose in her five films is a point of interest and a viable course of study. This project uses her fifth and latest film, Bling Ring (2013), to showcase Coppola's merits as a filmmaker at the intersection of box office and critical appeal. I first describe the current filmmaking landscape in terms of gender. Using studies by Dr. Martha Lauzen from San Diego State University and the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media to illustrate the statistical lack of a female presence in creative film roles and also why it is important to have women represented in above-the-line positions. Then I used close readings of Bling Ring to analyze formal aspects of Sofia Coppola's filmmaking style namely her use of distinct color palettes, provocative soundtracks, car shots, and tableaus. Third and lastly I went on to describe the sociocultural aspects of Coppola's interpretation of the "Sling Ring." The way the film explores the relationships between characters, portrays parents as absent or misguided, and through film form shows the pervasiveness of celebrity culture, Sofia Coppola has given Bling Ring has a central ii message, substance, and meaning: glamorous contemporary celebrity culture can have dangerous consequences on unchecked youth. -

Graphic No Vels & Comics

GRAPHIC NOVELS & COMICS SPRING 2020 TITLE Description FRONT COVER X-Men, Vol. 1 The X-Men find themselves in a whole new world of possibility…and things have never been better! Mastermind Jonathan Hickman and superstar artist Leinil Francis Yu reveal the saga of Cyclops and his hand-picked squad of mutant powerhouses. Collects #1-6. 9781302919818 | $17.99 PB Marvel Fallen Angels, Vol. 1 Psylocke finds herself in the new world of Mutantkind, unsure of her place in it. But when a face from her past returns only to be killed, she seeks vengeance. Collects Fallen Angels (2019) #1-6. 9781302919900 | $17.99 PB Marvel Wolverine: The Daughter of Wolverine Wolverine stars in a story that stretches across the decades beginning in the 1940s. Who is the young woman he’s fated to meet over and over again? Collects material from Marvel Comics Presents (2019) #1-9. 9781302918361 | $15.99 PB Marvel 4 Graphic Novels & Comics X-Force, Vol. 1 X-Force is the CIA of the mutant world—half intelligence branch, half special ops. In a perfect world, there would be no need for an X-Force. We’re not there…yet. Collects #1-6. 9781302919887 | $17.99 PB Marvel New Mutants, Vol. 1 The classic New Mutants (Sunspot, Wolfsbane, Mirage, Karma, Magik, and Cypher) join a few new friends (Chamber, Mondo) to seek out their missing member and go on a mission alongside the Starjammers! Collects #1-6. 9781302919924 | $17.99 PB Marvel Excalibur, Vol. 1 It’s a new era for mutantkind as a new Captain Britain holds the amulet, fighting for her Kingdom of Avalon with her Excalibur at her side—Rogue, Gambit, Rictor, Jubilee…and Apocalypse. -

“Why So Serious?” Comics, Film and Politics, Or the Comic Book Film As the Answer to the Question of Identity and Narrative in a Post-9/11 World

ABSTRACT “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD by Kyle Andrew Moody This thesis analyzes a trend in a subgenre of motion pictures that are designed to not only entertain, but also provide a message for the modern world after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The analysis provides a critical look at three different films as artifacts of post-9/11 culture, showing how the integration of certain elements made them allegorical works regarding the status of the United States in the aftermath of the attacks. Jean Baudrillard‟s postmodern theory of simulation and simulacra was utilized to provide a context for the films that tap into themes reflecting post-9/11 reality. The results were analyzed by critically examining the source material, with a cultural criticism emerging regarding the progression of this subgenre of motion pictures as meaningful work. “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Mass Communications Area by Kyle Andrew Moody Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2009 Advisor ___________________ Dr. Bruce Drushel Reader ___________________ Dr. Ronald Scott Reader ___________________ Dr. David Sholle TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... III CHAPTER ONE: COMIC BOOK MOVIES AND THE REAL WORLD ............................................. 1 PURPOSE OF STUDY ................................................................................................................................... -

Generic Transformation in the Superhero Film Genre by Noah Goodman

GENERIC TRANSFORMATION IN THE SUPERHERO FILM GENRE BY NOAH GOODMAN Reaffirmation of Myth: Humorous Burlesque: • Questions the • Pokes fun at the traditional heroic overused tropes of the values of the genre genre • Lighter, comedic tone • Reaffirms traditional • Graphic violence as heroic values as comedy being true • Non-heroic protagonist • Enforces the idea of • Satirizes interconnection (i.e. interconnected the MCU) superhero films INTRODUCTION: According to film genre theorist, John G. Cawelti, there are four modes at which a film genre can undergo generic transformation. Cawelti states these modes are “humorous burlesque, evocation of nostalgia, demythologization of generic myth, and the affirmation of myth as myth” (Cawelti 295). Despite it being a relatively new film genre, the superhero genre has already had a multitude of films to already fit these four modes declared by Cawelti. However, no other films express these four modes as greatly as Tim Miller’s Deadpool (2016), Patty Jenkin’s Wonder Woman (2017), James Mangold’s Logan (2017), and Joe and Anthony Russo’s Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014), respectively. DEFINITION OFTERMS: • Humorous Burlesque: tropes used in the genre are situated in a way to invoke laughter and are satirized • Evocation of Nostalgia: uses genre conventions to recreate aura of the past while establishing a relationship to the present • Demythologization: invokes the traditional genre conventions and demonstrates them as inadequate and destructive • Reaffirmation of Myth: questions genre conventions and ultimately reaffirmed at least partially Demythologization: Evocation of • More realistic tone Nostalgia: • Reference to myth as • Repisodic nostalgia being inadequate and based around pop false culture • Disillusioned • Traditional, heroic protagonist protagonist with • Shows the violence of unwavering beliefs super heroic actions • Thematic mending of • Darker promotional past and present material societal issues. -

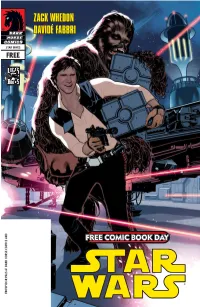

Zack Whedon Davidé Fabbri Zack Whedon 2/17/12 1:11 Pm ® S R

ZACKZACK WHEDONWHEDON ® DAVIDÉDAVIDÉ FABBRIFABBRI STAR WARS FREE ® FROM YOUR PALS AT DARK HORSE COMICS AND COMICS HORSE DARK AT PALS YOUR FROM FCBD12 SW-SEREN.indd 1 2/17/12 1:11 PM FCBD12 SW-SEREN.indd 2 tions, or locales, without satiric intent, is coincidental. Printed by Cadmus Communications, Easton, PA, U.S.A. tions, orlocales,without satiricintent,iscoincidental.Printed byCadmusCommunications,Easton, PA, Anyresemblancetoactual persons(livingordead),events,institu either aretheproduct oftheauthor’simaginationorareused fictitiously. writtenpermissionofDarkHorse Comics,Inc.Names,characters,places,andincidentsfeaturedinthispublication without theexpress categories andcountries.Allrightsreserved. Noportionofthispublicationmaybereproducedortransmitted,inanyform or are ©2012LucasfilmLtd.DarkHorse Comics® andtheDarkHorselogoaretrademarksofComics,Inc.,registered inva Wars andillustrationsforStar Text ©2012LucasfilmLtd.&™.Allrightsreserved.Usedunderauthorization. Milwaukie, OR97222.StarWars ArtoftheBadDeal,”May2012.PublishedbyDarkHorseComics, Inc.,10956SEMainStreet, WARS—“The STAR FREE COMICBOOK DAY: RONDA D MICHAEL A D ZACK WHEDON ZACK advertising sales: (503) 905-2370 » comic shop locator service: (888)266-4226 service: (503)905-2370»comicshop locator sales: advertising ALLA ALLA DA AVIDÉ FABBRI AVIDÉ MIKE RANDY RANDY M H M C assistant editor assistant collection editor P F HRISTIAN REDD cover art SIERRA R lettering V T ATTISON T ICHARDSON INA ALESSI ECCHIA talk about this issue online at: online at: aboutthisissue talk Pencils HO UGHES Colors STRADLE publisher D script designer YE YE AVID M editor Inks HAHN LINS AS Y STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS ANDERMAN at lucas licensing. ANDERMAN at ALDERS, CAROL special thankstoJ ROEDER Comics! Horse Dark from pals this your at free offering enjoy please afirst-timer, or time reader along you’re whether But Emperor.