MASTROMATTEO-THESIS-2021.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Download

140 ALBERTA LAW REVIEW [VOL. XXXV, NO. I 1996] SNAPSHOTS THEN AND NOW: FEMINISM AND THE LAW IN ALBERTA ANNALISE ACORN• The pioneering efforts of women such as Emily Les efforts audacieux de certaines pionnieres tel/es Murphy in Alberta during the early part of this que Emily Murphy en Alberta au debut du siecle ont cenJury effected legal change and altered women's fail evoluer /es lois et transforme la condition lives. Women began to see the law as a vehicle for feminine. Les femmes ont commence apercevoir la social change, entitling them to property and giving Loi comme un outil de changement social /eur rise to new expectations that a world of "true donnant droit a la propriete et porteur d'un monde happiness" would emerge. de« reel bonheur ». However, this time also saw the beginnings of Mais cette epoque a egalement donne lieu a des fractures and divisions in the modern feminist fractures et des divisions fondees sur la race, la movement based on race, class and sexual clas.se et /'orientation sexuelle dan.s le mouvement orientation. Late twentieth century feminist theory feministe moderne. La theorie feministe de la fin du has, in part, been an attempt to overcome XX siecle s 'efforce en partie de surmonter /es theoretical imperatives of universalism (the nature imperatifs de /'universalisme (la nature de of mankind) and essentia/ism (features common to I 'humanile} et de I 'essentialisme (/es all women}, with mixed results. Nonetheless, the caracteri.stiques communes a toutes /es femmes) failures of feminists in this area who have acted at avec un succes mitige. -

Emily Murphy

Emily Murphy These questions can help to guide a student’s viewing of the Emily Murphy biography. 1. What metaphors are commonly used by historians to describe Emily Murphy? 2. How would you describe Emily’s childhood and education? List important characteristics she developed or events that occurred during this period in her life. 3. What prompted Emily Murphy to begin writing her series of Janey Canuck books? Whose travels were these books based on? 4. Which type of feminism is Emily said to have supported? How is it described in the video? 5. What is the name of the legislation to protect women’s property rights that Emily fought for? What did this legislation guarantee women? 6. Which other influential Canadian women did Emily meet and become life-long friends with while she was living in Edmonton, Alberta? 7. How did Emily assist other Canadian women during the campaign for women’s suffrage? When was the vote given to women in Alberta? In Manitoba? In Ontario? 8. Which of Emily’s campaigns resulted in her appointment as a Court Magistrate? Why was this a cause for celebration around the world? 9. Why was the Montréal’s Women’s Club’s nomination of Emily for a seat in the Canadian Senate left in limbo for six years? How did Emily’s brother, Bill, renew her hopes of becoming appointed to the Canadian Senate? 10. Identify the four other women who make up the Famous Five with Emily. Briefly describe each of their contributions. 11. What question did the Famous Five pose to the Supreme Court of Canada, and later, the British Privy Council? 12. -

Canada January 2008

THE READING OF MACKENZIE KING by MARGARET ELIZABETH BEDORE A thesis submitted to the Department of History in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen's University Kingston, Ontario, Canada January 2008 Copyright © Margaret Elizabeth Bedore, 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-37063-6 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-37063-6 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Nnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

National Historic Sites of Canada System Plan Will Provide Even Greater Opportunities for Canadians to Understand and Celebrate Our National Heritage

PROUDLY BRINGING YOU CANADA AT ITS BEST National Historic Sites of Canada S YSTEM P LAN Parks Parcs Canada Canada 2 6 5 Identification of images on the front cover photo montage: 1 1. Lower Fort Garry 4 2. Inuksuk 3. Portia White 3 4. John McCrae 5. Jeanne Mance 6. Old Town Lunenburg © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, (2000) ISBN: 0-662-29189-1 Cat: R64-234/2000E Cette publication est aussi disponible en français www.parkscanada.pch.gc.ca National Historic Sites of Canada S YSTEM P LAN Foreword Canadians take great pride in the people, places and events that shape our history and identify our country. We are inspired by the bravery of our soldiers at Normandy and moved by the words of John McCrae’s "In Flanders Fields." We are amazed at the vision of Louis-Joseph Papineau and Sir Wilfrid Laurier. We are enchanted by the paintings of Emily Carr and the writings of Lucy Maud Montgomery. We look back in awe at the wisdom of Sir John A. Macdonald and Sir George-Étienne Cartier. We are moved to tears of joy by the humour of Stephen Leacock and tears of gratitude for the courage of Tecumseh. We hold in high regard the determination of Emily Murphy and Rev. Josiah Henson to overcome obstacles which stood in the way of their dreams. We give thanks for the work of the Victorian Order of Nurses and those who organ- ized the Underground Railroad. We think of those who suffered and died at Grosse Île in the dream of reaching a new home. -

Women Judges in Prairie Canada 1916 - 1980

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2014-12-05 Bench-Breakers? Women Judges in Prairie Canada 1916 - 1980 Jakobsen, Pernille Jakobsen, P. (2014). Bench-Breakers? Women Judges in Prairie Canada 1916 - 1980 (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/25108 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/1956 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca i THE UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Bench-Breakers? Women Judges in Prairie Canada 1916 – 1980 by Pernille Jakobsen A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY CALGARY, ALBERTA NOVEMBER, 2014 © Pernille Jakobsen 2014 ii Abstract Between 1916 and 1980 a small number of women magistrates and judges adjudicated in courtrooms across the Prairie Provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. Often they worked in “family court,” through its historic incarnations including juvenile courts, women’s courts, and domestic relations tribunals. The first of these women, practicing between 1916 and 1935, included magistrates Emily Murphy and Alice Jamieson in Alberta, and judge Jean Ethel MacLachlan in Saskatchewan. None of these women held law degrees or membership within the legal profession, but all three had a “motherly outlook.” Murphy and Jamieson’s expertise was derived from their leading roles in influential women’s organizations and connections to the suffrage and dower campaigns. -

T H E C Itizen's Gu Id E

The Citizen’s Guide to the Alberta Legislature Ninth Edition Where did builders find the marble for the Legislature Building? How is an American state Legislature different from our provincial Legislature? What happens during a typical legislative session? This booklet is designed to address these and many to theto Alberta Legislature other questions related to the history, traditions and procedures of the Legislative Assembly of Alberta. The booklet also contains review questions and answers as well as a glossary of parliamentary terminology. THE CITIZEN’S GUIDE NINTH EDITION © 2016 Table of Contents 1. The Foundation 1 The Parliamentary System in Alberta 2 A Constitutional Monarchy 6 The Levels of Government 10 Two Styles of Governing: Provincial and State Legislatures 14 2. Representing the People 17 The Provincial General Election 18 You and Your MLA 22 Executive Council 29 3. Rules and Traditions 31 Symbols and Ceremonies: The Mace and the Black Rod 32 The Speaker 36 Parliamentary Procedure 39 4. Getting the Business Done 41 How the Assembly Works 42 Taking Part 46 Making Alberta’s Laws 50 Putting Your Tax Dollars to Work 54 The Legislative Assembly Office 57 It’s All in Hansard 60 5. The Building and Its Symbols 63 The Legislature Building 64 The Emblems of Alberta 68 The Legislative Assembly Brand 71 Glossary 73 Index 81 Study Questions 93 Study Questions 94 Answer Key 104 Selected Bibliography 109 The contents of this publication reflect the practices and procedures of the Legislative Assembly as of January 1, 2016. Readers are advised to check with the Legislative Assembly Office to ensure that the information as it relates to parliamentary practice within the Legislative Assembly is up to date. -

Moral Panics and Sexuality Discourse: the Oppression of Chinese Male Immigrants in Canada, 1900-1950

Moral Panics and Sexuality Discourse: The Oppression of Chinese Male Immigrants in Canada, 1900-1950 Stephanie Weber Racial hierarchy in Canada between 1900 and 1950 shaped the way immigrant “others” were portrayed in White-Anglophone Canadian discourse. Crimes involving ethnic minorities were explained in racial and cultural terms that fed stereotypes and incited fears that served to marginalize and oppress minority groups, particularly people of colour.1 Chinese men, for instance, were targets of a racial and sexual othering that resulted in the distrust and oppression of this group. Moral and sexual threats posed by Chinese immigrants were part of an overarching fear of Chinese inGluence on white Canada known as the “Yellow Peril.” The myth of the Yellow Peril “interwove all of the predominant discourse” in the early twentieth century, encouraging and exacerbating “accusations of vice, gambling, interracial seduction, drug use, and other ‘moral offences’” against the Chinese in Canada.2 Racist perception of Chinese immigrant men in Canada helped to “shore up prevailing imperialist ideologies, marking out Asian societies as ‘backward’ and ‘primitive.’”3 As Constance Backhouse explains, Chinese immigrant men were perceived to have “inferior moral standards”4 and, like other men of colour, were believed to be “incapable of controlling their sexual desires.”5 Moral anxieties of this kind contributed to public support for racist legislation such as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1923, and other laws and regulations which served to limit the entry of Chinese persons into Canada and to socially and economically marginalize those already settled. As Stanley Cohen concludes in 1972’s Folk Devils and Moral Panics, a moral panic refers to when “a condition, episode, person or group of persons emerges to become deGined as a threat to societal values and interests.”6 According to some 1 Franca Iacovetta, Gatekeepers,: Reshaping Immigrant Lives in Cold War Canada (Toronto: Between the Lines, 2006), 20. -

The Persons' Case (1929) {The Famous Five: Henrietta Muir

The Persons' Case (1929) {The Famous Five: Henrietta Muir Edwards, Nellie McClung, Louise McKinney, Emily Murphy and Irene Parlby}. Issue: Can a women hold the office of Senator? [The Canadian government said no, but put the matter before the courts. Question they put before Supreme Court Does the word "Persons" in section 24 of the British North America Act 1867, include female persons? The Supreme Court of Canada replied that the word "person" did not include female persons. Fortunately, for Canadian women, the Famous 5 were able to appeal to an even higher court, the British Privy Council. The question was duly submitted to them and on October 18, 1929 they overturned the decision of the Supreme Court by deciding that the word "person" did indeed include persons of the female gender. The word "person" always had a much broader meaning than its strict legal definition, and it therefore had been used to exclude women from university degrees, from voting, from entering the professions and from holding public office. The definition of "person" became a threshold test of women's equality. Only when Canadian women had been legally recognized as persons could they gain access to public life. After 1929, the door was open for women to lobby for further changes to achieve equality. As women across Canada can confirm today, that struggle continues. The 1929 Persons' Case is one of the major achievements by Canadians for Canadians. The Famous 5 succeeded in having women defined as "persons" in Section 24 of the British North America Act and thereby, eligible for appointment to the Senate. -

Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future

Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada Contents Introduction ......................................................................................... 1 Commission activities ......................................................................... 27 The history ........................................................................................... 41 The legacy ............................................................................................ 183 The challenge of reconciliation .......................................................... 237 !" • T#$%& ' R()*+)!,!-%!*+ C*..!//!*+ Introduction or over a century, the central goals of Canada’s Aboriginal policy were to eliminate Aboriginal governments; ignore Aboriginal rights; terminate the Treaties; and, Fthrough a process of assimilation, cause Aboriginal peoples to cease to exist as dis- tinct legal, social, cultural, religious, and racial entities in Canada. 0e establishment and operation of residential schools were a central element of this policy, which can best be described as “cultural genocide.” Physical genocide is the mass killing of the members of a targeted group, and biological genocide is the destruction of the group’s reproductive capacity. Cultural genocide is the destruction of those structures -

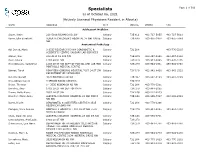

Specialists Page 1 of 509 As of October 06, 2021 (Actively Licensed Physicians Resident in Alberta)

Specialists Page 1 of 509 as of October 06, 2021 (Actively Licensed Physicians Resident in Alberta) NAME ADDRESS CITY POSTAL PHONE FAX Adolescent Medicine Soper, Katie 220-5010 RICHARD RD SW Calgary T3E 6L1 403-727-5055 403-727-5011 Vyver, Ellie Elizabeth ALBERTA CHILDREN'S HOSPITAL 28 OKI DRIVE Calgary T3B 6A8 403-955-2978 403-955-7649 NW Anatomical Pathology Abi Daoud, Marie 9-3535 RESEARCH RD NW DIAGNOSTIC & Calgary T2L 2K8 403-770-3295 SCIENTIFIC CENTRE CALGARY LAB SERVICES Alanen, Ken 242-4411 16 AVE NW Calgary T3B 0M3 403-457-1900 403-457-1904 Auer, Iwona 1403 29 ST NW Calgary T2N 2T9 403-944-8225 403-270-4135 Benediktsson, Hallgrimur 1403 29 ST NW DEPT OF PATHOL AND LAB MED Calgary T2N 2T9 403-944-1981 493-944-4748 FOOTHILLS MEDICAL CENTRE Bismar, Tarek ROKYVIEW GENERAL HOSPITAL 7007 14 ST SW Calgary T2V 1P9 403-943-8430 403-943-3333 DEPARTMENT OF PATHOLOGY Bol, Eric Gerald 4070 BOWNESS RD NW Calgary T3B 3R7 403-297-8123 403-297-3429 Box, Adrian Harold 3 SPRING RIDGE ESTATES Calgary T3Z 3M8 Brenn, Thomas 9 - 3535 RESEARCH RD NW Calgary T2L 2K8 403-770-3201 Bromley, Amy 1403 29 ST NW DEPT OF PATH Calgary T2N 2T9 403-944-5055 Brown, Holly Alexis 7007 14 ST SW Calgary T2V 1P9 403-212-8223 Brundler, Marie-Anne ALBERTA CHILDREN HOSPITAL 28 OKI DRIVE Calgary T3B 6A8 403-955-7387 403-955-2321 NW NW Bures, Nicole DIAGNOSTIC & SCIENTIFIC CENTRE 9 3535 Calgary T2L 2K8 403-770-3206 RESEARCH ROAD NW Caragea, Mara Andrea FOOTHILLS HOSPITAL 1403 29 ST NW 7576 Calgary T2N 2T9 403-944-6685 403-944-4748 MCCAIG TOWER Chan, Elaine So Ling ALBERTA CHILDREN HOSPITAL 28 OKI DR NW Calgary T3B 6A8 403-955-7761 Cota Schwarz, Ana Lucia 1403 29 ST NW Calgary T2N 2T9 DiFrancesco, Lisa Marie DEPARTMENT OF PATHOLOGY (CLS) MCCAIG Calgary T2N 2T9 403-944-4756 403-944-4748 TOWER 7TH FLOOR FOOTHILLS MEDICAL CENTRE 1403 29TH ST NW Duggan, Maire A. -

FAMOUS FIVE CHALLENGE Purpose

FAMOUS FIVE CHALLENGE Purpose: The purpose of this challenge is to learn about the ‘Persons’ Case, the women who helped to bring changes to Canadian legislature to allow women to have a vote and to learn about women's rights. All branches must complete the first section Sparks and Brownies: do 3 of following activities. Guides: do 4 of the following activities. Pathfinders and Rangers do 5 of the following activities. Section #1 – The ‘Persons’ Case • Learn what the ‘Persons’ Case was • Learn at least one thing about the 5 women (the Famous Five) who were involved in the ‘Persons’ Case. Section #2 – Activities • Make a hat to depict one of the Famous Five women and explain why this describes her • Have a tea party with the Famous Five. You can make life size cutouts of the women or have girls/adults play the parts of these women. Have a tea party and ask them questions about what it was like to participate in this. This can be a great bridging activity as well • Visit the Famous Five monument in either Calgary or Ottawa. You can also locate this on a map and using pictures of this can make drawings of the location and put yourself in there as a virtual visitor • Use the interactive story to learn more about the Famous Five women (see supplement for the story) or create your own story about these women • Make a collection of newspaper or internet articles regarding issues that pertain to women today. Discuss the importance of these with your unit • Create a skit about the Famous Five • Complete the Famous Five Word search (see supplement) -

![“The True [Political] Mothers of Today”: Farm Women And](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8295/the-true-political-mothers-of-today-farm-women-and-4398295.webp)

“The True [Political] Mothers of Today”: Farm Women And

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Saskatchewan's Research Archive “THE TRUE [POLITICAL] MOTHERS OF TODAY”: FARM WOMEN AND THE ORGANIZATION OF EUGENIC FEMINISM IN ALBERTA A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts In the Department of History University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By SHEILA RAE GIBBONS Copyright Sheila Rae Gibbons, August 2012. All rights reserved PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of History University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A5 OR Dean of the College of Graduate Studies and Research University of Saskatchewan 107 Administration Place Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A2 i ABSTRACT In this thesis, I examine the rise of feminist agrarian politics in Alberta and the ideological basis for their support of extreme health care reforms, including eugenics.