FIDH Serbia-Montenegro the Failures of the Transition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

METHODOLOGICAL APPENDIX: FIELDWORK and ARCHIVES in TORN STATES Even Though I Had Anticipated Methodological Problems When I

METHODOLOGICAL APPENDIX: FIELDWORK AND ARCHIVES IN TORN STATES Even though I had anticipated methodological problems when I set out to investigate the relation of separatism to organized crime, I completely misidentified what the main ones were to be. Having repeatedly done fieldwork in Kosovo, including an interview-based study of nationalism among students at Belgrade and Priština Universities (Mandic 2015), I expected the primary problems to be logistical. Since crossing “borders” (as separatists call them) or “administrative boundaries” (as host state bureaucrats call them) was often time-consuming and costly, and since ignorance of Albanian, Georgian, Ossetian and Russian often required a translator as well as a tour guide, I thought traveling would be the greatest difficulty. In fact, the two main difficulties were access to archives – by far the greatest challenge, and the most costly research component – and evaluating the credibility of sources – steering clear of nationalist propaganda and quasi-scientific references. Below I explore some of the dilemmas, challenges and regrets I have faced in the hopes that they aid future students of the topic. Fieldwork With the help of a Research Fellowship from the Minda de Ginzburg Center for European Studies in the 2013-4 academic year, I was able to travel extensively in Serbia/Kosovo and Georgia/South Ossetia interviewing experts, conducting informal ethnographies and exploring archives. I spent a total of five and a half months in Serbia, three of which were in Kosovo and three and a half months in Georgia, four weeks of which were in South Ossetia. I visited the four relevant capitals, cities/towns along separatist borders, and major towns on separatist territory. -

Civil-Military Features of the FRY

Civil-Military Features of the FRY 18. november 2002. - Dr Miroslav Hadzic Dr Miroslav Hadžić Faculty of Political Science Belgrade / Centre for Civil-Military Relations Occasional paper No.4 The direction of the profiling of civilian military relations in Serbia/FR Yugoslavia1 is determined by the situational circumstances and policies of the participants of different backgrounds and uneven strength. The present processes however, are the direct product of consequence of the disparate action of parties from the Democratic Opposition of Serbia (DOS) coalition, which have ruled the local political scene since the ousting of Milošević. It was their mediation that introduced the war and authoritarian heritage to the political scene, making it an obstacle for changing the encountered civil-military relations. The ongoing disputes within the DOS decrease, but also conceal the fundamental reasons for the lack of pro-democratic intervention of the new authorities in the civil-military domain. Numerous military and police incidents and affairs that have marked the post-October period in Serbia testify to this account.2 The incidents were used for political confrontation within the DOS instead as reasons for reform. This is why disputes regarding the statues of the military, police and secret services, as well as control of them have been reduced to the personal and/or political conflict between FRY President Vojislav Koštunica and Serbian Premier Zoran Djindjić.3 However, the analysis of the "personal equation" of the most powerful DOS leaders may reveal only differences in their political shade and intonation, but cannot reveal the fundamental reasons why Serbia has remained on the foundations of Milošević’s system. -

CDDRL Number 114 WORKING PAPERS June 2009

CDDRL Number 114 WORKING PAPERS June 2009 Youth Movements in Post- Communist Societies: A Model of Nonviolent Resistance Olena Nikolayenko Stanford University Center on Democracy, Development, and The Rule of Law Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies Additional working papers appear on CDDRL’s website: http://cddrl.stanford.edu. Center on Democracy, Development, and The Rule of Law Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies Stanford University Encina Hall Stanford, CA 94305 Phone: 650-724-7197 Fax: 650-724-2996 http://cddrl.stanford.edu/ About the Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law (CDDRL) CDDRL was founded by a generous grant from the Bill and Flora Hewlett Foundation in October in 2002 as part of the Stanford Institute for International Studies at Stanford University. The Center supports analytic studies, policy relevant research, training and outreach activities to assist developing countries in the design and implementation of policies to foster growth, democracy, and the rule of law. About the Author Olena Nikolayenko (Ph.D. Toronto) is a Visiting Postdoctoral Scholar and a recipient of the 2007-2009 post-doctoral fellowship from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Her research interests include comparative democratization, public opinion, social movements, youth, and corruption. In her dissertation, she analyzed political support among the first post-Soviet generation grown up without any direct experience with communism in Russia and Ukraine. Her current research examines why some youth movements are more successful than others in applying methods of nonviolent resistance to mobilize the population in non-democracies. She has recently conducted fieldwork in Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Serbia, and Ukraine. -

Revolutionary Tactics: Insights from Police and Justice Reform in Georgia

TRANSITIONS FORUM | CASE STUDY | JUNE 2014 Revolutionary Tactics: Insights from Police and Justice Reform in Georgia by Peter Pomerantsev with Geoffrey Robertson, Jovan Ratković and Anne Applebaum www.li.com www.prosperity.com ABOUT THE LEGATUM INSTITUTE Based in London, the Legatum Institute (LI) is an independent non-partisan public policy organisation whose research, publications, and programmes advance ideas and policies in support of free and prosperous societies around the world. LI’s signature annual publication is the Legatum Prosperity Index™, a unique global assessment of national prosperity based on both wealth and wellbeing. LI is the co-publisher of Democracy Lab, a journalistic joint-venture with Foreign Policy Magazine dedicated to covering political and economic transitions around the world. www.li.com www.prosperity.com http://democracylab.foreignpolicy.com TRANSITIONS FORUM CONTENTS Introduction 3 Background 4 Tactics for Revolutionary Change: Police Reform 6 Jovan Ratković: A Serbian Perspective on Georgia’s Police Reforms Justice: A Botched Reform? 10 Jovan Ratković: The Serbian Experience of Justice Reform Geoffrey Robertson: Judicial Reform The Downsides of Revolutionary Maximalism 13 1 Truth and Reconciliation Jovan Ratković: How Serbia Has Been Coming to Terms with the Past Geoffrey Robertson: Dealing with the Past 2 The Need to Foster an Opposition Jovan Ratković: The Serbian Experience of Fostering a Healthy Opposition Russia and the West: Geopolitical Direction and Domestic Reforms 18 What Georgia Means: for Ukraine and Beyond 20 References 21 About the Author and Contributors 24 About the Legatum Institute inside front cover Legatum Prosperity IndexTM Country Factsheet 2013 25 TRANSITIONS forum | 2 TRANSITIONS FORUM The reforms carried out in Georgia after the Rose Revolution of 2004 were Introduction among the most radical ever attempted in the post-Soviet world, and probably the most controversial. -

A Pillar of Democracy on Shaky Ground

Media Programme SEE A Pillar of Democracy on Shaky Ground Public Service Media in South East Europe RECONNECTING WITH DATA CITIZENS TO BIG VALUES – FROM A Pillar of Democracy of Shaky on Ground A Pillar www.kas.de www.kas.dewww.kas.de Media Programme SEE A Pillar of Democracy on Shaky Ground Public Service Media in South East Europe www.kas.de Imprint Copyright © 2019 by Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Media Programme South East Europe Publisher Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. Authors Viktorija Car, Nadine Gogu, Liana Ionescu, Ilda Londo, Driton Qeriqi, Miroljub Radojković, Nataša Ružić, Dragan Sekulovski, Orlin Spassov, Romina Surugiu, Lejla Turčilo, Daphne Wolter Editors Darija Fabijanić, Hendrik Sittig Proofreading Boryana Desheva, Louisa Spencer Translation (Bulgarian, German, Montenegrin) Boryana Desheva, KERN AG, Tanja Luburić Opinion Poll Ipsos (Ivica Sokolovski), KAS Media Programme South East Europe (Darija Fabijanić) Layout and Design Velin Saramov Cover Illustration Dineta Saramova ISBN 978-3-95721-596-3 Disclaimer All rights reserved. Requests for review copies and other enquiries concerning this publication are to be sent to the publisher. The responsibility for facts, opinions and cross references to external sources in this publication rests exclusively with the contributors and their interpretations do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung. Table of Content Preface v Public Service Media and Its Future: Legitimacy in the Digital Age (the German case) 1 Survey on the Perception of Public Service -

SIGNALIZAM U FONDOVIMA BIBLIOTEKE SANU Posebna Biblioteka Miroljuba TODOROVIĆA (PB 19)

SIGNALIZAM U FONDOVIMA BIBLIOTEKE SANU Posebna biblioteka Miroljuba TODOROVIĆA (PB 19) Biblioteka SANU osnovana je Ustavom i ustrojenijem Društva srpske slovesnosti od 7. novembra 1841. godine. Razvijajući se u sklopu Društva, menjala je i svoj naziv u skladu sa izmenama naziva Društva. Od 1864. godine bila je Biblioteka Srpskog učenog društva, potom, od 1886. Biblioteka Srpske kraljevske akademije, 1945. postala je Biblioteka Srpske akademije nauka, da bi 1960. godine dobila sadašnji naziv – Biblioteka Srpske akademije nauka i umetnosti. Dimitrije Tirol, član Društva srpske slovesnosti i dobrotvor srpskog naroda, poklonio je 1842. godine Društvu u dva maha 89 knjiga koje su predstavljale početni fond Biblioteke, i tada je ona i počela sa radom. Početni fond uvećavan je poklonima i izdanjima društva, ustanovljena je razmena sa domaćim i inostranim akademijama i naučnim društvima. Kupovina knjiga počela je 1851. godine. Biblioteka je delimično otvorena za javnost 1952. godine U ovom momentu, može se govoriti o fondu od 1.300.000 jedinica knjižne i neknjižne građe od čega je preko 60% na stranim jezicima. U elektronskoj bazi postoji 125.000 zapisa. U okviru ovako bogatog fonda, osobit značaj pridaje se tzv. posebnim bibliotekama . To su ponajčešće zapravo biblioteke-legati, primljene poklonom ili testamentom, a samo u iznimnim slučajevima biblioteke koje su kupovane na osnovu posebnih odluka SANU. Njih u ovom trenutku ima 36, i svaka je na svoj način presek ne samo jednog vremena već i života, interesovanja i opusa velikih stvaralaca na svim poljima ljudske delatnosti. Na knjigama tih biblioteka nalaze se posvete koje govore o dinamičnim i dramatičnim stvaralačkim prijateljstvima. Jasno je da kao takve postaju teško procenljive. -

Oslo Scholars Program 2020

OSLO SCHOLARS PROGRAM 2020 The Oslo Scholars Program offers undergraduates with a demonstrated interest in human rights and international political issues an opportunity to attend the Oslo Freedom Forum and to spend their summer interning with some of the world’s leading human rights defenders and activists. Applications are due March 13, 2020 at 11:59pm SUMMER 2020 INTERNSHIPS Srdja Popovic (CANVAS) Srdja Popovic is a founding member of Otpor! the Serbian civic youth movement that played a pivotal role in the ousting of Slobodan Milosevic. He is a prominent nonviolent expert and the leader of CANVAS, a nonprofit organization dedicated to working with nonviolent democratic movements around the world. CANVAS works with citizens from more than 30 countries, sharing nonviolent strategies and tactics that were used by Otpor!. A native of Belgrade, Popovic has promoted the principles and strategies of nonviolence as tools for building democracy since helping to found the Otpor! movement. Otpor! began in 1998 as a university- based organization; after only two years, it quickly grew into a national movement, attracting more than 70,000 supporters. A student of nonviolent strategy, Popovic translated several works on the subject, such as the books of American scholar Gene Sharp, for distribution. He also authored “Blueprint for Revolution”, a handbook for peaceful protesters, activists, and community organizers. After the overthrow of Milosevic, Popovic served in the Serbian National Assembly from 2000 to 2003. He served as an environmental affairs advisor to the prime minister. He left the parliament in 2003 to start CANVAS. The organization has worked with people in 46 countries to transfer knowledge of effective nonviolent tactics and strategies. -

Terrorist Threats by Balkans Radical Islamist to International Security

Darko Trifunović1 Оригинални научни рад University of Belgrade UDK 323.285:28]:355.02(497) Serbia Milan Mijalkovski2 University of Belgrade Serbia TERRORIST THREATS BY BALKANS RADICAL ISLAMIST TO INTERNATIONAL SECURITY Abstract The decade-long armed conflict in the Balkans from 1991 to 2001, greatly misrepresented in the Western public, were the biggest defeat for the peoples of the former Yugoslavia, a great defeat for Europe - but a victory for global jihad. Radical Islamists used the wars to recruit a large number of Sunni Muslims in the Balkans (Bosnian and Herzagovina and Albanian) for the cause of political Islam and militant Jihad. Converts to Wahhabi Islam not only provide recruits for the so-called “White Al-Qaeda,” but also exhibit growing territorial claims and seek the establishment of a “Balkan Caliphate.” Powers outside the Balkans re- gard this with indifference or even tacit approval. Radical Islamist activity is en- dangering the security of not only Serbia, Macedonia, Montenegro and Bosnia- Herzegovina, but also Europe and the world. Key Words: Balkans, Wahhabi, Salafi, radical Islamist, terrorism, Al-Qaeda Introduction In order to understand correctly the ongoing processes in the Islamic circles in the Balkans, it is necessary to understand all processes that occurred and occur in the Middle East and its circles of Islamic fundamentalists. Balkans’ groups of Islamic fundamentalists are inextricably connected with organizations of Islamic fundamentalists originating from the Middle East. Early as 1989, Prof. dr Miroljub Jevtić, one of the most eminent political scientists of religion, had been warning on danger and connection of the Middle East Islamic fundamen- talists with the ones on the Balkans sharing the same ideas3. -

Football and Politics: Serbia in Transition

Football and Politics: Serbia in Transition Behar Xharra Viadrina Summer University The Culture of Football: Power, Passion and Politics Class: Political Economy of Football Football and Politics: Serbia in Transition THE STORY OF WAR From Football Fields to War Battles: The Story of Arkan, Delije and Tigers Reputation building and FC Obilic http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:%C5%BDeljko_Ra%C5%BEnatovi%C4%87.jpg See movie from 6:00 – 8:00 at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z1DsSsKPrmM Football and Politics: Serbia in Transition INTERNATIONAL POLITICS United Nations Security Council Resolution 757, adopted on May 30, 1992… the Council condemned the failure of the authorities in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro) to implement Resolution 752. (g) limit participation in sporting events in the country;… The Council further decided that the sanctions should.. UN SC Resolution 757: http://www.un.org/documents/sc/res/1992/scres92.htm http://www.totalprosports.com/2011/06/27/this-day-in-sports-history-june-27th-denmark- soccer/ Football and Politics: Serbia in Transition POLITICS FROM THE PITCH "Peace, not War" - unique message of the Italian Lazio players Sinisa Mihajlovic and Dejan Stankovic before the game Lazio-Milan “Yugoslav football player Zoran Mirkovic protests against the NATO aggression wearing T-shirt saying in Italian "Peace, no War" as he sits on the bench of the Juventus Torino” http://www.arhiva.serbia.gov.rs/news/1999-06/08/12425.html Football and Politics: Serbia in Transition NATIONALISM FROM THE STANDS http://www.supersport.com/football/european-championships/news/101013/Platini_Blatter_condemn_Serbian_hooligans http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/23277147/ns/world_news-europe/t/protesters-burn-us-embassy-serbia/#.T9fd6bVSTEU Football and Politics: Serbia in Transition HOOLIGANISM Hooligans or Gangsters? ~ Wikileaks cable …a mix of ‘football toughs’ and organized crime elements. -

Serbian Reform Stalls Again

SERBIAN REFORM STALLS AGAIN 17 July 2003 ICG Balkans Report N°145 Belgrade/Brussels TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION: OPERATION SABRE ................................................................. 1 II. ACHIEVEMENTS ......................................................................................................... 3 A. HAGUE COOPERATION ..........................................................................................................3 B. CIVILIAN CONTROL OVER THE ARMED FORCES ......................................................................6 C. MILOSEVIC-ERA PARALLEL STRUCTURES.............................................................................7 D. NEW LEGISLATION................................................................................................................7 III. BACKWARDS STEPS................................................................................................... 8 A. THE MEDIA...........................................................................................................................9 B. THE JUDICIARY ...................................................................................................................12 C. HUMAN RIGHTS ..................................................................................................................13 D. MILOSEVIC’S SECURITY ORGANS........................................................................................14 IV. WHY -

Nonviolent Struggle : 50 Crucial Points : a Strategic Approach to Everyday Tactics / Srdja Popovic, Andrej Milivojeic, Slobodan Djinovic ; [Comments by Robert L

NONVIOLENT STRUGGLE 50 crucial points CANVAS Center for Applied NonViolent Action and Strategies NONVIOLENT STRUGGLE 50 CRUCIAL POINTS NONVIOLENT STRUGGLE 50 CRUCIAL POINTS A strategic approacH TO EVERYDAY tactics Srdja Popovic • Andrej Milivojevic • Slobodan Djinovic CANVAS Centre for Applied NonViolent Action and Strategies (CANVAS) Belgrade 2006. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction: How to read this book? . 10 This publication was prepared pursuant to the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) Grant USIP-123-04F, I Before You Start . 12 April 1, 2005. Chapter 1. Introduction to Strategic Nonviolent Conflict . 14 First published in Serbia in 2006 by Srdja Popovic, Andrej Milivojevic and Slobodan Djinovic Chapter 2. The Nature, Models and Sources of Political Power . 24 Copyright © 2006 by Srdja Popovic, Andrej Milivojevic Chapter 3. Pillars of Support: How Power is Expressed . 32 and Slobodan Djinovic All rights reserved. II Starting Out . .38 The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommen- dations expressed in this publication are those of the Chapter 4. Assessing Capabilities and Planning . 42 author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Chapter 5. Planning Skills: The Plan Format . 50 United States Institute of Peace. Chapter 6. Targeted Communication: Message Development . 58 Graphic design by Ana Djordjevic Chapter . Let the World Know Your Message: Comments by Robert L. Helvey and Hardy Merriman Photo on cover by Igor Jeremic Performing Public Actions . 66 III Running a Nonviolent Campaign . 2 Printed by Cicero, Belgrade 500 copies, first edition, 2006. Chapter 8. Building a Strategy: From Actions to Campaigns . 6 Produced and printed in Serbia Chapter 9. Managing a Nonviolent Campaign: Material Resources . -

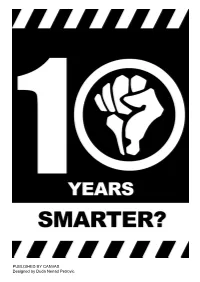

Chronology of Events – a Brief History of Otpor PUBLISHED by CANVAS

Chronology of Events – A Brief History of Otpor PUBLISHED BY CANVAS Designed by Duda Nenad Petrovic RESISTANCE! Chronology of Events – A Brief History of Otpor Chronology of Events – A Brief History of Otpor May 26, 1998 – University Act passed. November 4, 1998 – The concert organized by the ANEM (Association of Independent Electronic Media) under the October 20, 1998 – Media Act passed. slogan “It’s not like Serbs to be quiet” was held. Otpor ac- tivists launched a seven-day action “Resistance is the an- End of October 1998 – In response to the new Univer- swer”, within which they distributed flyers with provocative sity Act and Media Act, which were contrary to students’ questions relating to endless resignation and suffering of interests, the Student Movement Otpor was formed. all that we had been going through and slogans such as Among Otpor’s founders were Srdja Popovic, Slobodan “Bite the system, live the resistance”. Homen, Slobodan Djinovic, Nenad Konstantinovic, Vu- kasin Petrovic, Ivan Andric, Jovan Ratkovic, Andreja Sta- menokovic, Dejan Randjic, Ivan Marovic. The group was soon joined by Milja Jovanovic, Branko Ilic, Pedja Lecic, Sinisa Sikman, Vlada Pavlov from Novi Sad, Stanko La- zentic, Milan Gagic, Jelena Urosevic and Zoran Matovic from Kragujevac and Srdjan Milivojevic from Krusevac. In the beginning, among the core creators of Otpor were Bo- ris Karaicic, Miodrag Gavrilovic, Miroslav Hristodulo, Ras- tko Sejic, Aleksa Grgurevic and Aleksandar Topalovic, but they left the organization later. During this period, Nenad Petrovic, nicknamed Duda, a Belgrade-based designer, designed the symbol of Otpor – a clenched fist. In the night between November 2 and 3, 1998, four students were arrested for spraying the fist and slogans “Death to fascism” and “Resistance for freedom”: Teodo- ra Tabacki, Marina Glisic, Dragana Milinkovic and Nikola Vasiljevic.