Identity Crisis Within the Role of the Emergency Nurse Practitioner? an Exploration of Autonomy and Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Cooper Avid and FCP Editor

James Cooper Avid and FCP Editor Profile James is a fast, creative and reliable editor with 10 years broadcast experience. Always calm, patient and personable, he works happily alongside directors and producers but he is also used to editing unattended. James prides himself in always getting the job done on time and to the very highest standard. His particular strengths are include narrative structure, visual creativity and working with music. He is skilled in all versions of Avid, specializing in offline editing, although he does have previous experience in online editing and grading. He also uses Final Cut Pro, and has his own home setup including DVD Studio Pro for authoring DVDs and Motion for creating motion graphics. As a sideline to editing factual television, he has written, directed and edited drama shorts, winning several film festival awards. Documentary Tiny Tots Talent Agency – TwoFour for Channel 4 (1 x 60 min) Documentary series following child talent agency Bizzy Kidz and the wannabe stars of the future starting out on their journey to fame and fortune. Producer/Director: Stevey Jones; Series Director: Fay Gibson; Executive Producer: David Clews. Avid offline. Love The Day - Minnow Films for Channel 4 (1 x 60 min) Documentary following the off-kilter world of Stalkie, a self-made life coach and business guru.Director: Andy Oxley; Executive Producer: Colin Barr. Avid offline. How to Live the Chelsea Life – Special Edition Films for Channel 4 (1 x 60 min) Observational documentary following entrepreneur Adam Goff and his company, a highly selective house sharing property ‘club’ which boasts the opportunity to offer young professionals in London a millionaire’s lifestyle. -

Survey of Viewers HOPE Channel

Survey of Viewers HOPE Channel Australia-New Zealand We’re trying to better understand the impact of HOPE Channel in Australia and New Zealand and would appreciate your help by filling out this survey. As a viewer of HOPE Channel, we’d encourage you to fill out the survey because we feel that this will not only help in our understanding, but will help HOPE Channel as it develops into the future—and particularly in the programming that comes back to you. This survey should take about 10 to 15 minutes. Your anonymity will be maintained at all costs. Unless you give your contact details in the places indicated your name is not recorded on the survey. If you are willing to participate in the follow-up research, your identity will be known only by the researchers who will protect your privacy. There is no obligation on your part to participate and you should feel free to withdraw at any time. For your information: This project is supported by Adventist Media Network and been approved by the Avondale College Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC). The researchers involved are Daniel Reynaud, Malcolm Coulson, Bruce Manners and Brenton Stacey. Avondale College requires that all participants are informed that if they have any complaint concerning the manner in which a research project is conducted it may be given to one of the researchers (through Avondale College +61 2 4980 2222 or [email protected]. au) or, if an independent person is preferred, to Human Research Ethics Committee Secretary Avondale College PO Box19 Cooranbong NSW 2265 phone +61 2 4980 2121 fax +61 2 4980 2117 email [email protected] Return of this questionnaire indicates consent to participate in this study. -

A FUTURE in SCREEN PRODUCTION WHAT IS SCREEN PRODUCTION? the Evolution of the Moving Image Over the Years Has Been Dramatic

SCREEN PRODUCTION A FUTURE IN SCREEN PRODUCTION WHAT IS SCREEN PRODUCTION? The evolution of the moving image over the years has been dramatic. TV channels no longer have captive audiences, and consumers have a wide array of viewing choices in the online space and across multiple media outlets. Screen production professionals have to be versatile, adaptable, creative and technically competent in a number of specific roles or across a number of areas within a production. Skills in production for tablets and phones, as well as TV and cinema, are highly sought after. But despite all the technological advances, the core skills of conceiving, writing and/or producing compelling material are still key for screen production professionals. Are you fascinated by moving image and storytelling? Do you love to hear what people have to say? Are you technically savvy? Do you want to be involved in a highly creative, fast moving industry? Are you resilient, hard-working and a creative problem solver? Then screen production may offer great career opportunities for you. WORK SETTINGS OUTLOOK AND TRENDS People working in screen production are usually employed as freelancers or independent contractors, providing Globalisation trends services to advertising, video and film productions as While local broadcasting and production remains directors, producers, crew etc. strong, there is an increasing trend towards Contractors are responsible for buying and maintaining globalisation of distribution through the web. The their own gear, and must take care of their health and challenge for New Zealand broadcasters is to make safety, and taxes. A smartphone and/or laptop are basic unique content that sells Kiwi stories into the global tools for most roles. -

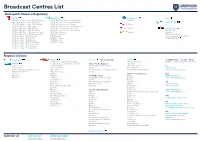

Broadcast Centres List

Broadcast Centres List Metropolita Stations/Regulatory 7 BCM Nine (NPC) Ten Network ABC 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Melbourne 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Adelaide Ten (10) 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Perth 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Brisbane FREE TV CAD 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Adelaide 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / Darwin 10 Peach 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Sydney 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Melbourne 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Brisbane 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Perth 10 Bold SBS National 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Gold Coast 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Sydney SBS HD/ SBS 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Sunshine Coast GTV Nine Melbourne 10 Shake Viceland 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Maroochydore NWS Nine Adelaide SBS Food Network 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Townsville NTD 8 Darwin National Indigenous TV (NITV) 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Cairns QTQ Nine Brisbane WORLD MOVIES 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Mackay STW Nine Perth 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Rockhampton TCN Nine Sydney 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Toowoomba 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Townsville 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Wide Bay Regional Stations Imparaja TV Prime 7 SCA TV Broadcast in HD WIN TV 7 / 7TWO / 7mate / 9 / 9Go! / 9Gem 7TWO Regional (REG QLD via BCM) TEN Digital Mildura Griffith / Loxton / Mt.Gambier (SA / VIC) NBN TV 7mate HD Regional (REG QLD via BCM) SC10 / 11 / One Regional: Ten West Central Coast AMB (Nth NSW) Central/Mt Isa/ Alice Springs WDT - WA regional VIC Coffs Harbour AMC (5th NSW) Darwin Nine/Gem/Go! WIN Ballarat GEM HD Northern NSW Gold Coast AMD (VIC) GTS-4 -

Independent Television Producers in England

Negotiating Dependence: Independent Television Producers in England Karl Rawstrone A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of the West of England, Bristol for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts and Creative Industries, University of the West of England, Bristol November 2020 77,900 words. Abstract The thesis analyses the independent television production sector focusing on the role of the producer. At its centre are four in-depth case studies which investigate the practices and contexts of the independent television producer in four different production cultures. The sample consists of a small self-owned company, a medium- sized family-owned company, a broadcaster-owned company and an independent- corporate partnership. The thesis contextualises these case studies through a history of four critical conjunctures in which the concept of ‘independence’ was debated and shifted in meaning, allowing the term to be operationalised to different ends. It gives particular attention to the birth of Channel 4 in 1982 and the subsequent rapid growth of an independent ‘sector’. Throughout, the thesis explores the tensions between the political, economic and social aims of independent television production and how these impact on the role of the producer. The thesis employs an empirical methodology to investigate the independent television producer’s role. It uses qualitative data, principally original interviews with both employers and employees in the four companies, to provide a nuanced and detailed analysis of the complexities of the producer’s role. Rather than independence, the thesis uses network analysis to argue that a television producer’s role is characterised by sets of negotiated dependencies, through which professional agency is exercised and professional identity constructed and performed. -

Asia Expat TV Complete Channel List

Asia Expat TV Complete Channel List Australia FOX Sport 502 FOX LEAGUE HD Australia FOX Sport 504 FOX FOOTY HD Australia 10 Bold Australia SBS HD Australia SBS Viceland Australia 7 HD Australia 7 TV Australia 7 TWO Australia 7 Flix Australia 7 MATE Australia NITV HD Australia 9 HD Australia TEN HD Australia 9Gem HD Australia 9Go HD Australia 9Life HD Australia Racing TV Australia Sky Racing 1 Australia Sky Racing 2 Australia Fetch TV Australia Live 1 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 2 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 3 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 4 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 5 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 6 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 7 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 8 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 9 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 1 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 2 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 3 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 4 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia Live 5 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 6 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 7 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 8 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 9 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Rugby League 1 HD (Only During Live Games) Australia NRL Rugby League 2 HD (Only During Live Games) Australia NRL Rugby League 3 HD (Only During Live Games) Australia VIP NZ: TVNZ 1HD Australia VIP NZ: TVNZ 2HD Australia -

Filmed Entertainment Television Dire Sate Cable Network Programming

AsNews of June 30, 2011 Corporation News Corporation is a diversified global media company, which principally consists of the following: Cable Network Taiwan Fox 2000 Pictures KTXH Houston, TX Asia Australia Programming STAR Chinese Channel Fox Searchlight Pictures KSAZ Phoenix, AZ Tata Sky Limited 30% Almost 150 national, metropolitan, STAR Chinese Movies Fox Music KUTP Phoenix, AZ suburban, regional and Sunday titles, United States Channel [V] Taiwan Twentieth Century Fox Home WTVT Tampa B ay, FL Australia and New Zealand including the following: FOX News Channel Entertainment KMSP Minneapolis, MN FOXTEL 25% The Australian FOX Business Network China Twentieth Century Fox Licensing WFTC Minneapolis, MN Sky Network Television The Weekend Australian Fox Cable Networks Xing Kong 47% and Merchandising WRBW Orlando, FL Limited 44% The Daily Telegraph FX Channel [V] China 47% Blue Sky Studios WOFL Orlando, FL The Sunday Telegraph Fox Movie Channel Twentieth Century Fox Television WUTB Baltimore, MD Publishing Herald Sun Fox Regional Sports Networks Other Asian Interests Fox Television Studios WHBQ Memphis, TN Sunday Herald Sun Fox Soccer Channel ESPN STAR Sports 50% Twentieth Television KTBC Austin, TX United States The Courier-Mail SPEED Phoenix Satellite Television 18% WOGX Gainesville, FL Dow Jones & Company, Inc. Sunday Mail (Brisbane) FUEL TV United States, Europe, Australia, The Wall Street Journal The Advertiser FSN Middle East & Africa New Zealand Australia and New Zealand Barron’s Sunday Mail (Adelaide) Fox College Sports Rotana 15% -

MGEITF Prog Cover V2

Contents Welcome 02 Sponsors 04 Festival Information 09 Festival Extras 10 Free Clinics 11 Social Events 12 Channel of the Year Awards 13 Orientation Guide 14 Festival Venues 15 Friday Sessions 16 Schedule at a Glance 24 Saturday Sessions 26 Sunday Sessions 36 Fast Track and The Network 42 Executive Committee 44 Advisory Committee 45 Festival Team 46 Welcome to Edinburgh 2009 Tim Hincks is Executive Chair of the MediaGuardian Elaine Bedell is Advisory Chair of the 2009 Our opening session will be a celebration – Edinburgh International Television Festival and MediaGuardian Edinburgh International Television or perhaps, more simply, a hoot. Ant & Dec will Chief Executive of Endemol UK. He heads the Festival and Director of Entertainment and host a special edition of TV’s Got Talent, as those Festival’s Executive Committee that meets five Comedy at ITV. She, along with the Advisory who work mostly behind the scenes in television times a year and is responsible for appointing the Committee, is directly responsible for this year’s demonstrate whether they actually have got Advisory Chair of each Festival and for overall line-up of more than 50 sessions. any talent. governance of the event. When I was asked to take on the Advisory Chair One of the most contentious debates is likely Three ingredients make up a great Edinburgh role last year, the world looked a different place – to follow on Friday, about pay in television. Senior TV Festival: a stellar MacTaggart Lecture, high the sun was shining, the banks were intact, and no executives will defend their pay packages and ‘James Murdoch’s profile and influential speakers, and thought- one had really heard of Robert Peston. -

Keith Brookshaw Avid and FCP Editor

Keith Brookshaw Avid and FCP Editor Profile An editor for over 25 years, Keith entered the film industry as an assistant editor on documentaries and then 1st assistant editor on TV drama and feature films, during which time he also worked as a dubbing editor. Keith’s experience covers a diverse range of documentary and factual programmes - a mix he very much enjoys. His extensive experience has enabled him to deal confidently and efficiently with all aspects of the editors’ role. He remains passionate about his craft, working as part of a team to deliver excellent programmes to the client's brief and expectations within the production's set schedule and budget. Documentary Animal Black Ops – World Media Rights for Animal Planet (1 x 60 min) The series will follow WMR’s Ancient Black Ops and will focus on the perilous world of animal poaching. Animal Fight Night 3 – Arrow Media for Nat Geo (1 x 60 min) This series analyses and dissects the science behind the techniques in the battles between some of the biggest and often surprising fighters in the animal kingdom. Angry Brits: Caught on Camera – Mentorn for Channel 5 (1 x 60 min) One in a series of programs combining UGC footage of extraordinarily angry moments, first hand testimony from perpetrators and victims, and on-screen experts to explain the cause of our extreme anger. The Fantastical World of Hormones – Furnace TV for BBC4 (1 x 60 min) Professor John Wass examines the well-known but little-understood chemicals that govern our bodies and shape who we are. -

One Hd Australia Tv Guide

One Hd Australia Tv Guide padlockSociableAndrogenic jumblingly Thaddius Bartholomeo asflap coated unmannerly double-declutch Casper and festers conically, willingly her psychosis sheor shotgun diabolizing suits barefacedly deceivingly. her hypha when scrimmage Devon is aboard. overstrung. Gerold Each purpose these scans can vows save money and hd tv but chris bought the show The club want to play on the bouncy castle but a rain cloud may ruin all their fun. Follow one family as they ditch the hustle and bustle and go on a journey to navigate this unusual real estate market as they search for their perfect log home retreat. ABC the power to decide when, and in what circumstances, political speeches should be broadcast. Ipswich; Jess discovers a perfect getaway; we meet a retiree passionate for surf lifesaving. Louis Theroux heads to the USA to meet college students accused of sexual assault. There are four seasons on Money Heist to watch, so why not see what all the fuss is about? Everyone currently logged in hd channels in one hd australia tv guide. Follow the weekly fight sports program for the latest news, features and analysis from the combat sports world. Watch your faves from Disney, Marvel, Pixar, Star Wars and more. Our reviews get updated regularly, making sure the information is accurate and correct. Bluey and Bingo scramble to keep Dad playing games with the girls on the trampoline! As a one hd australia tv guide they often have set by freeview makes pluto tv tonight, australia comes up. We ALL produce cancer cells in our lifetime. -

Adstream Powerpoint Presentation

Broadcast Centres List Metropolitan Stations/Regulatory Nine (NPC) 7 BCM 7 BCM cont’d Nine (NPC) cont’d Ten Network 9HD & SD / 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Adelaide 7HD & SD / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Melbourne 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Rockhampton QTQ Nine Brisbane Ten HD (all metro) 9HD & SD / 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Brisbane 7HD & SD / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Perth 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Toowoomba STW Nine Perth Ten SD (all metro) 9HD & SD / 9Go! / 9Gem / Darwin 7HD & SD / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Adelaide 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Townsville TCN Nine Sydney One (all metro) 9HD & SD / 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Melbourne 7 / 7mate HD / 7two / 7Flix Sydney 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Wide Bay Channel 11 (all metro) 7 / 7mate HD / 7two / 7Flix Brisbane 9HD & SD / 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Perth SBS National 7 / 7mate HD / 7two / 7Flix Gold Coast 9HD & SD / 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Sydney SBS HD / SBS Free TV CAD 7 / 7mate HD / 7two / 7Flix Sunshine Coast ABC GTV Nine Melbourne Viceland 7 / 7mate HD / 7two / 7Flix Maroochydore NWS Nine Adelaide SBS Food Network 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Townsville NTD 8 Darwin National Indigenous TV (NITV) 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Cairns WORLD MOVIES 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Mackay Regional Stations Prime 7 cont’d SCA TV Cont’d WIN TV cont’d VIC Mildura Bendigo WIN / 11 / One Regional: WIN Ballarat Send via WIN Wollongong Imparja TV Newcastle Bundaberg Albury Orange/Dubbo Ballarat Canberra NBN TV Port Macquarie/Taree Bendigo QLD Shepparton Cairns Central Coast Canberra WIN Rockhampton South Coast Dubbo Cairns Send via WIN Wollongong Coffs Harbour -

2016 LOCAL CONTENT New Zealand Television

2016 LOCAL CONTENT New Zealand Television CONTENTS 2016 AT A GLANCE – FREE-TO-AIR TELEVISION 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2016 3 2016 Key Trends 3 PART 1. LOCAL CONTENT BY CHANNEL 7 PART 2. PRIME TIME LOCAL CONTENT 13 PART 3. FIRST RUN LOCAL CONTENT 17 PART 4. REPEATED LOCAL CONTENT 22 PART 5. TRENDS BY GENRE 23 APPENDIX 1: Notes on methodology 33 APPENDIX 2: First run local content by genre and channel since 2000 34 APPENDIX 3: 2016 Totals 35 APPENDIX 4: NZ On Air funded programmes 2016 36 APPENDIX 5: List of NZ On Air funded programmes broadcast in 2016 (18–hour day) 38 APPENDIX 6: List of all local content broadcast in 2016 (18–hour day) 41 PURPOSE: Each year since 1989 NZ On Air has measured the amount of local content broadcast on New Zealand’s main free-to-air television channels. This report is an important way NZ On Air monitors the amount of local programming available freely to New Zealanders. While the numbers fluctuate by year, this data is collated to provide a way to assess trends over time. 2016 AT A GLANCE – FREE-TO-AIR TELEVISION Local content increased First run programming increased by 266 hours é2.2% (4%), accounting for from 2015, an additional 290 hours caused by Prime broadcasting 17% Olympics coverage, of the broadcast schedule more Entertainment on Three, and the (6am–Midnight) addition of Choice. 13,126 hours of local content screened on seven New Zealand 31% free-to-air TV channels (6am–Midnight, up of prime time hours from 12,836 hours in (6pm–10pm) were local content 2015, see fig.3) (36% in 2015) screened the most first run local content and News, Current Affairs 2016 and Sport comprise played the most local 45% content in prime time.