The Politics of Public Behaviour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Danny Kruger Selected As Conservative Parliamentary Candidate for Devizes

Press Release t (Press) 020 7984 8121 t (Broadcast) 020 7984 8180 f 020 7222 1135 Saturday 9 November 2019 Danny Kruger selected as Conservative Parliamentary candidate for Devizes A close aide of Prime Minister Boris Johnson has been selected as the Conservative Parliamentary candidate for Devizes. Danny Kruger was chosen at a selection meeting at the Corn Exchange in Devizes this afternoon (Saturday), which was attended by over 300 (CHECK) local Conservative members. Danny has been political secretary to the Prime Minister since July 2019 and has previously worked as chief speechwriter to David Cameron when he was Leader of the Opposition and an adviser to former Conservative Party leaders Iain Duncan Smith and Michael Howard. He helped to develop Mr Cameron’s ‘Big Society’ agenda and is keen to promote the same ethos in Devizes, empowering volunteers, businesses and community groups to tackle local issues and challenges. Danny is keen to boost local NHS services, support the police to tackle rural crime, ensure schools get their fair share of increased funding, push for greater infrastructure investment, enhance the rail and bus network and help businesses be more productive. He is a strong supporter of the Armed Forces and wants to ensure the relocation of service families to Wiltshire is a success for everyone. Danny supports Mr Johnson’s determination to get Brexit done as soon as possible and forge a positive new relationship with the EU. “I’m proud and excited to be selected as the Conservative Parliamentary candidate for Devizes and I’m looking forward to knocking on doors, meeting local people and addressing their concerns,” said Danny. -

The China Strategy America Needs DOWNLOAD CSS Notes, Books, Mcqs, Magazines

Race and health: far from equal Afghanistan, a premature evacuation Remaking the British state Golf’s biggest hitters NOVEMBER 21ST–27TH 2020 The China strategy America needs DOWNLOAD CSS Notes, Books, MCQs, Magazines www.thecsspoint.com Download CSS Notes Download CSS Books Download CSS Magazines Download CSS MCQs Download CSS Past Papers The CSS Point, Pakistan’s The Best Online FREE Web source for All CSS Aspirants. Email: [email protected] BUY CSS / PMS / NTS & GENERAL KNOWLEDGE BOOKS ONLINE CASH ON DELIVERY ALL OVER PAKISTAN Visit Now: WWW.CSSBOOKS.NET For Oder & Inquiry Call/SMS/WhatsApp 0333 6042057 – 0726 540141 FPSC Model Papers 50th Edition (Latest & Updated) By Imtiaz Shahid Advanced Publishers For Order Call/WhatsApp 03336042057 - 0726540141 CSS Solved Compulsory MCQs From 2000 to 2020 Latest & Updated Order Now Call/SMS 03336042057 - 0726540141 Contents The Economist November 21st 2020 3 The world this week United States 6 A summary of political 23 To the bitter end and business news 24 Missile defence 25 Charles Koch Leaders 25 The State Department 9 China and America A new grand bargain 26 Midwestern corruption 27 Development v cemeteries 10 American politics The art of losing 27 Charters and covid-19 10 Afghanistan 28 Lexington Barack Leaving too soon Obama’s book 11 Sovereign debt A better way not to pay The Americas 29 Mexico and cannabis On the cover 14 Race and health Wanted: more data 30 Illegal fishing in Ecuador As president, Joe Biden should 16 Reforming Britain 31 Bello Peru’s chaotic aim to strike a grand bargain Remaking the state politics with America’s democratic allies: leader, page 9, and briefing, page 19. -

Domestic Analogy in Proposals for World Order, 1814-1945

Domestic analogy in proposals for world order, 1814-1945: the transfer of legal and political principles from the domestic to the international sphere in thought on international law and relations HIDEMI SUGANAMI Thesis submitted for the Degree of Ph.D. The London School of Economics and Political Science, University of London 1985 2 ABSTRACT The ways in which legal and political principles obtaining within states can profitably be transferred to the relations of states are among the contentious issues in the study of international relations, and the term 'domestic analogy' is used to refer to the argument which supports such transfer. The 'domestic analogy' is analogical reasoning according to which the conditions of order between states are similar to those of order within them, and therefore those institutions which sustain order within states should be transferred to the international system. However, despite the apparent division among writers on international relations between those who favour this analogy and those who are critical of it, no clear analysis has so far been made as to precisely what types of proposal should be treated as exemplifying reliance on this analogy. The first aim of this thesis is to clarify the range and types of proposal this analogy entails. The thesis then examines the role the domestic analogy played in ideas about world order in the period between 1814 and 1945. Particular attention is paid to the influence of changing circumstances in the domestic and international spheres upon the manner and the extent of the use of this analogy. In addition to the ideas of major writers on international law and relations, the creation of the League of Nations and of the United Nations is also examined. -

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 Diane ABBOTT MP

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Labour Conservative Diane ABBOTT MP Adam AFRIYIE MP Hackney North and Stoke Windsor Newington Labour Conservative Debbie ABRAHAMS MP Imran AHMAD-KHAN Oldham East and MP Saddleworth Wakefield Conservative Conservative Nigel ADAMS MP Nickie AIKEN MP Selby and Ainsty Cities of London and Westminster Conservative Conservative Bim AFOLAMI MP Peter ALDOUS MP Hitchin and Harpenden Waveney A Labour Labour Rushanara ALI MP Mike AMESBURY MP Bethnal Green and Bow Weaver Vale Labour Conservative Tahir ALI MP Sir David AMESS MP Birmingham, Hall Green Southend West Conservative Labour Lucy ALLAN MP Fleur ANDERSON MP Telford Putney Labour Conservative Dr Rosena ALLIN-KHAN Lee ANDERSON MP MP Ashfield Tooting Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Conservative Conservative Stuart ANDERSON MP Edward ARGAR MP Wolverhampton South Charnwood West Conservative Labour Stuart ANDREW MP Jonathan ASHWORTH Pudsey MP Leicester South Conservative Conservative Caroline ANSELL MP Sarah ATHERTON MP Eastbourne Wrexham Labour Conservative Tonia ANTONIAZZI MP Victoria ATKINS MP Gower Louth and Horncastle B Conservative Conservative Gareth BACON MP Siobhan BAILLIE MP Orpington Stroud Conservative Conservative Richard BACON MP Duncan BAKER MP South Norfolk North Norfolk Conservative Conservative Kemi BADENOCH MP Steve BAKER MP Saffron Walden Wycombe Conservative Conservative Shaun BAILEY MP Harriett BALDWIN MP West Bromwich West West Worcestershire Members of the House of Commons December 2019 B Conservative Conservative -

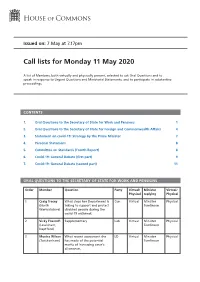

Call List for Mon 11 May 2020

Issued on: 7 May at 7.17pm Call lists for Monday 11 May 2020 A list of Members, both virtually and physically present, selected to ask Oral Questions and to speak in response to Urgent Questions and Ministerial Statements; and to participate in substantive proceedings. CONTENTS 1. Oral Questions to the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions 1 2. Oral Questions to the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs 4 3. Statement on covid-19: Strategy by the Prime Minister 7 4. Personal Statement 8 5. Committee on Standards (Fourth Report) 8 6. Covid-19: General Debate (first part) 9 7. Covid-19: General Debate (second part) 11 ORAL QUESTIONS TO THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK AND PENSIONS Order Member Question Party Virtual/ Minister Virtual/ Physical replying Physical 1 Craig Tracey What steps her Department is Con Virtual Minister Physical (North taking to support and protect Tomlinson Warwickshire) disabled people during the covid-19 outbreak. 2 Vicky Foxcroft Supplementary Lab Virtual Minister Physical (Lewisham, Tomlinson Deptford) 3 Munira Wilson What recent assessment she LD Virtual Minister Physical (Twickenham) has made of the potential Tomlinson merits of increasing carer's allowance. 2 Call lists for Monday 11 May 2020 Order Member Question Party Virtual/ Minister Virtual/ Physical replying Physical 4 Karin Smyth What steps she has taken to Lab Virtual Minister Physical (Bristol South) help ensure prompt payment Tomlinson of access to work costs during the covid-19 outbreak. 5 Richard What recent assessment she Con Virtual Minister Virtual Graham has made of the effectiveness Quince (Gloucester) of the operation of universal credit. -

On Fraternity

On Fraternity On Fraternity Politics beyond liberty and equality Danny Kruger Civitas: Institute for the Study of Civil Society London Registered Charity No. 1085494 First Published April 2007 © The Institute for the Study of Civil Society 2007 77 Great Peter Street London SW1P 2EZ Civitas is a registered charity (no. 1085494) and a company limited by guarantee, registered in England and Wales (no. 04023541) email: [email protected] All rights reserved ISBN 978‐1‐903386‐57‐6 Independence: The Institute for the Study of Civil Society (Civitas) is a registered educational charity (No. 1085494) and a company limited by guarantee (No. 04023541). Civitas is financed from a variety of private sources to avoid over‐ reliance on any single or small group of donors. All publications are independently refereed. All the Institute’s publications seek to further its objective of promoting the advancement of learning. The views expressed are those of the authors, not of the Institute. Typeset by Civitas Printed in Great Britain by The Cromwell Press Trowbridge, Wiltshire Contents Page Author vi Author’s Acknowledgements vii Introduction The Wall and the Desert 1 1 Triangulation 12 2 Liberty and Equality 23 3 Fraternity 46 Afterword The Disordered Dialectic 88 Notes 91 v Author Danny Kruger is special adviser to David Cameron MP, the leader of the Conservative Party. He was formerly chief leader writer at the Daily Telegraph and director of studies at the Centre for Policy Studies. He has degrees in modern history from Edinburgh University (M.A., 1997) and Oxford University (D.Phil., 2000). vi Author’s Acknowledgements This essay has been quite long in the writing and I have benefited from a lot of help. -

Local Electricity Bill

Local Electricity Bill A B I L L TO Enable electricity generators to become local electricity suppliers; and for connected purposes. 1 Purpose The purpose of this Act is to encourage and enable the local supply of electricity. 2 Local electricity suppliers (1) An electricity generator may be a local electricity supplier. (2) In this section “electricity generator” has the same meaning as in section 6 of the Electricity Act 1989. (3) A local supplier must – (a) hold a local electricity supply licence, and (b) adhere to the conditions of that local electricity supply licence. 3 Amendment of the Electricity Act 1989 (1) The Electricity Act 1989 is amended as follows. (2) In section 6 (licences authorising supply, etc.), after subsection (1)(d), insert – “(da) a licence authorising a person to supply electricity to premises within a designated local area (“a local electricity supply licence”); (3) After section 6 insert – “6ZA Local electricity supply licences (1) Subject to it exercising its other functions under this Act the Gas and Electricity Markets Authority (“the Authority”) may grant a local electricity supply licence to a person who meets local electricity supply licence conditions. (2) The Authority must set local electricity supply licence conditions. (3) The Authority must specify the designated local area for each local electricity supply licence. (4) Before making any specification under subsection (3) the Authority must consult – (a) any relevant local authority; (b) any existing local electricity suppliers; (c) any persons who have, to the knowledge of the Authority, expressed an interest in becoming local electricity suppliers; (d) any other person who, in its opinion, has an interest in that matter. -

Chile: Background and U.S

Chile: Background and U.S. Relations name redacted Analyst in Latin American Affairs November 19, 2015 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R40126 Chile: Background and U.S. Relations Summary Chile, located along the Pacific coast of South America, is a politically stable, upper-middle- income nation of 18 million people. In 2013, Michelle Bachelet and her center-left “New Majority” coalition won the presidency and sizeable majorities in both houses of the Chilean Congress after campaigning on a platform of ambitious reforms designed to reduce inequality and improve social mobility. Since her inauguration to a four-year term in March 2014, President Bachelet has signed into law significant changes to the tax, education, and electoral systems. She has also proposed a number of other economic and social policy reforms, as well as a process for adopting a new constitution. Although a significant majority of the public initially supported the reforms, Chileans have grown more divided over time, with some groups pushing for more far- reaching policy changes and others calling for Bachelet to scale back her agenda. Disapproval of the reforms, a corruption scandal that implicated her son, and Chile’s slowing economy have taken a toll on President Bachelet’s approval rating, which has declined to 29%. Chile’s economic growth has slowed considerably in recent years, falling to 1.9% in 2014. Analysts have largely attributed the slowdown to the end of the global commodity boom and the coinciding drop in copper prices, which have a significant impact on the Chilean economy. There are also indications that the Bachelet Administration’s policy reforms may have reduced business confidence and dampened growth. -

Statism by Stealth

Statism by Stealth New Labour, new collectivism MARTIN MCELWEE AND ANDREW TYRIE MP CENTRE FOR POLICY STUDIES 57 Tufton Street London SW1P 3QL 2002 THE AUTHORS MARTIN MCELWEE took a double first in law from Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge before joining the Centre for Policy Studies as Deputy Editor. He now works for an international law firm in the City. His publications include The Great and Good?: The Rise of the New Class (Centre for Policy Studies, 2000); Leviathan at Large; the new regulator for the financial markets (with Andrew Tyrie MP, CPS, 2000); Small Government (CPS, 2001); and Judicial Review: Keeping Ministers in Check (Bow Group, 2002). ANDREW TYRIE has been Conservative Member of Parliament for Chichester since May 1997. His publications include A Cautionary Tale of EMU (CPS, 1991); The Prospects for Public Spending (Social Market Foundation, 1996); Reforming the Lords: a Conservative Approach (Conservative Policy Forum, 1998); Leviathan at Large; the new regulator for the financial markets (with Martin McElwee, CPS, 2000); Mr Blair’s Poodle: an Agenda for reviving the House of Commons (CPS, 2000); and Back from the Brink (Parliamentary Mainstream, 2001). ISBN No. 1 903219 41 8 Centre for Policy Studies, March 2002 Printed by The Chameleon Press, 5 – 25 Burr Road, London SW18 CONTENTS 1 Introduction 1 2 Regulation and industrial policy 5 3 Business and red tape 19 4 Education 25 5Health 33 6 Culture, Media and Sport 40 7 The Tsar phenomenon 45 8 Conclusion 48 Bibliography 50 The aim of the Centre for Policy Studies is to develop and promote policies that provide freedom and encouragement for individuals to pursue the aspirations they have for themselves and their families, within the security and obligations of a stable and law-abiding nation. -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Monday Volume 691 15 March 2021 No. 190 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 15 March 2021 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2021 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. HER MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT MEMBERS OF THE CABINET (FORMED BY THE RT HON. BORIS JOHNSON, MP, DECEMBER 2019) PRIME MINISTER,FIRST LORD OF THE TREASURY,MINISTER FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE AND MINISTER FOR THE UNION— The Rt Hon. Boris Johnson, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER—The Rt Hon. Rishi Sunak, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN,COMMONWEALTH AND DEVELOPMENT AFFAIRS AND FIRST SECRETARY OF STATE— The Rt Hon. Dominic Raab, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME DEPARTMENT—The Rt Hon. Priti Patel, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE DUCHY OF LANCASTER AND MINISTER FOR THE CABINET OFFICE—The Rt Hon. Michael Gove, MP LORD CHANCELLOR AND SECRETARY OF STATE FOR JUSTICE—The Rt Hon. Robert Buckland, QC, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE—The Rt Hon. Ben Wallace, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE—The Rt Hon. Matt Hancock, MP COP26 PRESIDENT—The Rt Hon. Alok Sharma, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR BUSINESS,ENERGY AND INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY—The Rt Hon. Kwasi Kwarteng, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND PRESIDENT OF THE BOARD OF TRADE, AND MINISTER FOR WOMEN AND EQUALITIES—The Rt Hon. Elizabeth Truss, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK AND PENSIONS—The Rt Hon. Dr Thérèse Coffey, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EDUCATION—The Rt Hon. -

To Download the Report As a .Pdf

progressivethethe progressiveSPRING 2010 conscienceconscience OF CLASHTHEGENERATIONS David WILLETTS Rafael BEHR Matthew TAYLOR Tim MONTGOMERIE OF CLASHTHE GENERATIONS David WILLETTS Rafael BEHR Matthew TAYLOR Tim MONTGOMERIE SPRING 2010 brightbright blue blue image ian muttoo Contributors Contents Anushka Asthana is the Policy Editor of The Observer Page 6 THE PROGCON ESSAY Rafael Behr is Chief Leader Writer for The Observer David Willetts calls on the babyboomers to act Damian Collins is the Conservative Parliamentary Candidate for Folkestone and Hythe and founding director of the Conservative Arts and Creative Page 8 THE INTERVIEW David Willetts Industries Network Danny Kruger reflects on his journey from Team Cameron to theatre with Tim Gill writes on childhood. His book No Fear: Growing up in a risk averse ex-offenders society was published in 2007 Pages 11-22 OPINION Nick Hillman is the Conservative Parliamentary Candidate for Cambridge and author of Quelling the Pensions Storm Matt Warman ponders over the post-bureaucratic age Rafael Behr on decentralisation and collective identity Danny Kruger is a former speechwriter to David Cameron and co-founder of Lucy Stone wants a greener future for our children OnlyConnect Rabbi Dr Jonathan Romain on faith schools Anushka Asthana applauds the modern man Matthew Taylor Penny Mansfield is Director of One Plus One, the relationship research Tim Gill returns to his childhood image: David Devin charity Page 14 THE POLITICS COLUMN Fiona Melville and David Skelton run Platform 10, a blog which -

Driving Growth Through Women's Economic Participation

THE % THE 51 51 % Driving Growth through Women’s Economic Participation Edited by DIANE WHITMORE SCHANZENBACH and RYAN NUNN The 51% Driving Growth through Women’s Economic Participation Edited by Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach and Ryan Nunn OCTOBER 2017 ii Acknowledgments The Hamilton Project wishes to thank members of its Advisory Council for their valuable contributions to this book. In particular, the Project is grateful to Roger C. Altman, Penny Pritzker, and Robert E. Rubin for helpful discussions and insights. The contents of this volume and the individual papers do not necessarily represent the views of individual Advisory Council members, nor do they necessarily represent the views of the institutions with which the papers’ authors are affiliated. The Hamilton Project is also grateful for the expert feedback provided by participants at the May 2017 authors’ conference held at the Brookings Institution. We appreciate the contributions of everyone who participated in that meeting. The editors appreciate insightful comments from Jay Shambaugh as well as the outstanding work of The Hamilton Project staff on this book. Kriston McIntosh provided expert guidance on all aspects of production. Lauren Bauer, Audrey Breitwieser, and David Dreyer contributed substantially to the development of the book. Patrick Liu, Megan Mumford, Greg Nantz, and Becca Portman provided superb research assistance. We also gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Karna Malaviya, Carmel Steindam, Alison Hope, Brianna Harden, Vesna Asanovic, Anna Rotrosen, and Melanie Gilarsky. The policy proposals included in this volume are proposals from the authors. As emphasized in The Hamilton Project’s original strategy paper, the Project was designed in part to provide a forum for leading thinkers across the nation to put forward innovative and potentially important economic policy ideas that share the Project’s broad goals of promoting economic growth, broad-based participation in growth, and economic security.