Lana Turner Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

230-Newsletter.Pdf

$5? The Poetry Project Newsletter Editor: Paul Foster Johnson Design: Lewis Rawlings Distribution: Small Press Distribution, 1341 Seventh Street, Berkeley, CA 94710 The Poetry Project, Ltd. Staff Artistic Director: Stacy Szymaszek Program Coordinator: Arlo Quint Program Assistant: Nicole Wallace Monday Night Coordinator: Macgregor Card Monday Night Talk Series Coordinator: Josef Kaplan Wednesday Night Coordinator: Stacy Szymaszek Friday Night Coordinator: Brett Price Sound Technician: David Vogen Videographer: Andrea Cruz Bookkeeper: Stephen Rosenthal Archivist: Will Edmiston Box Office: Courtney Frederick, Vanessa Garver, Jeffrey Grunthaner Interns/Volunteers: Nina Freeman, Julia Santoli, Alex Duringer, Jim Behrle, Christa Quint, Judah Rubin, Erica Wessmann, Susan Landers, Douglas Rothschild, Alex Abelson, Aria Boutet, Tony Lancosta, Jessie Wheeler, Ariel Bornstein Board of Directors: Gillian McCain (President), Rosemary Carroll (Treasurer), Kimberly Lyons (Secretary), Todd Colby, Mónica de la Torre, Ted Greenwald, Tim Griffin, John S. Hall, Erica Hunt, Jonathan Morrill, Elinor Nauen, Evelyn Reilly, Christopher Stackhouse, Edwin Torres Friends Committee: Brooke Alexander, Dianne Benson, Raymond Foye, Michael Friedman, Steve Hamilton, Bob Holman, Viki Hudspith, Siri Hustvedt, Yvonne Jacquette, Patricia Spears Jones, Eileen Myles, Greg Masters, Ron Padgett, Paul Slovak, Michel de Konkoly Thege, Anne Waldman, Hal Willner, John Yau Funders: The Poetry Project’s programs are made possible, in part, with public funds from The National Endowment for the Arts. The Poetry Project’s programming is made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature; and are supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, in partnership with the City Council. -

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

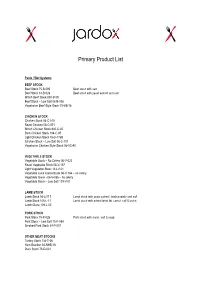

Primary Product List

Primary Product List Paste / Wet Systems BEEF STOCK Beef Stock 75-B-095 Beef stock with salt Beef Stock 14-B-028 Beef stock with yeast extract and salt British Beef Stock 800-B-09 Beef Stock – Low Salt 06-B-038 Vegetarian Beef Style Stock 75-VB-16 CHICKEN STOCK Chicken Stock 06-C-015 Roast Chicken 06-C-071 British Chicken Stock 800-C-02 Dark Chicken Stock 104-C-97 Light Chicken Stock 75-C-173B Chicken Stock – Low Salt 06-C-107 Vegetarian Chicken Style Stock 06-VC-40 VEGETABLE STOCK Vegetable Stock – No Celery 06-V-022 Roast Vegetable Stock 06-V-157 Light Vegetable Stock 143-V-01 Vegetable Juice Concentrate 06-V-164 – no celery Vegetable Glace –06-V-086 – no celery Vegetable Stock – Low Salt 109-V-01 LAMB STOCK Lamb Stock 06-L-017 Lamb stock with yeast extract, lamb powder and salt Lamb Stock 105-L-11 Lamb stock with added lamb fat, carrot, salt & onion Lamb Glace 109-L-05 PORK STOCK Pork Stock 75-P-026 Pork stock with onion, salt & sage Pork Stock – Low Salt 75-P-054 Smoked Pork Stock 34-P-001 OTHER MEAT STOCKS Turkey Stock 133-T-06 Ham Bouillon 34-NHB-16 Duck Stock 75-D-021 FISH STOCK Fish Stock 75-F-011 Lobster Stock 75-LOB-23 Fish & Shellfish Bouillon 06-F-004 Fish Stock 15-F-004 MUSHROOM STOCK Mushroom Stock 109-MU-6 Wild Mushroom Flavoured Stock 04-MU-02 Porcini Mushroom Stock 22-MU-37 ONION STOCK Onion Stock 06-O-016 Onion Glace 109-O-04 Roast Onion Stock 28-O-001 CHEESE STOCK Cheese Stock 75-CH-08 Mature Cheddar Stock 75-CH-20 Hard Italian Style Cheese Stock 75-PCH-4 Danish Blue style Cheese Stock 75-BLC-40 Nacho Cheese Stock 75-NAC-23 -

Jessica Lange Regis Dialogue Formatted

Jessica Lange Regis Dialogue with Molly Haskell, 1997 Bruce Jenkins: Let me say that these dialogues have for the better part of this decade focused on that part of cinema devoted to narrative or dramatic filmmaking, and we've had evenings with actors, directors, cinematographers, and I would say really especially with those performers that we identify with the cutting edge of narrative filmmaking. In describing tonight's guest, Molly Haskell spoke of a creative artist who not only did a sizeable number of important projects but more importantly, did the projects that she herself wanted to see made. The same I think can be said about Molly Haskell. She began in the 1960s working in New York for the French Film Office at that point where the French New Wave needed a promoter and a writer and a translator. She eventually wrote the landmark book From Reverence to Rape on women in cinema from 1973 and republished in 1987, and did sizable stints as the film reviewer for Vogue magazine, The Village Voice, New York magazine, New York Observer, and more recently, for On the Issues. Her most recent book, Holding My Own in No Man's Land, contains her last two decades' worth of writing. I'm please to say it's in the Walker bookstore, as well. Our other guest tonight needs no introduction here in the Twin Cities nor in Cloquet, Minnesota, nor would I say anyplace in the world that motion pictures are watched and cherished. She's an internationally recognized star, but she's really a unique star. -

March 2021 ACADEMIC BIOGRAPHY Lynn Keller E-Mail: Rlkeller@Wisc

March 2021 ACADEMIC BIOGRAPHY Lynn Keller E-mail: [email protected] Education: Ph.D., University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, 1981 Dissertation: Heirs of the Modernists: John Ashbery, Elizabeth Bishop, and Robert Creeley, directed by Robert von Hallberg M.A., University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, 1976 B.A., Stanford University, Palo Alto, California, 1973 Academic Awards and Honors: Bradshaw Knight Professor of Environmental Humanities (while director of CHE, 2016-2019) Fellow of the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, 2015-2016 Martha Meier Renk Bascom Professor of Poetry, January 2003 to August 2019; emerita to present UW Institute for Research in the Humanities, Senior Fellow, Fall 1999-Spring 2004 American Association of University Women Fellowship, July 1994-June 1995 Vilas Associate, 1993-1995 (summer salary 1993, 1994) Chancellor’s Award for Excellence in Teaching, 1989 University nominee for NEH Summer Stipend, 1986 Fellow, University of Wisconsin Institute for Research in the Humanities, Fall semester 1983 NEH Summer Stipend, 1982 Doctoral Dissertation awarded Departmental Honors, English Department, University of Chicago, 1981 Whiting Dissertation Fellowship, 1979-80 Honorary Fellowship, University of Chicago, 1976-77 B.A. awarded “With Distinction,” Stanford University, 1973 Employment: 2016-2019 Director, Center for Culture, History and Environment, Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies, UW-Madison 2014 Visiting Professor, Stockholm University, Stockholm Sweden, Spring semester 2009-2019 Faculty Associate, Center for Culture, History, and Environment, UW-Madison 1994-2019 Full Professor, English Department, University of Wisconsin-Madison [Emerita after August 2019] 1987-1994 Associate Professor, English Department, University of Wisconsin-Madison 1981-1987 Assistant Professor, English Department, University of Wisconsin-Madison 1981 Instructor, University of Chicago Extension (course on T.S. -

A Star Has Died: Affect and Stardom in a Domestic Melodrama

QRF 21(2) #14679 Quarterly Review of Film and Video, 21:95–105, 2004 Copyright © Taylor & Francis Inc. ISSN: 1050-9208 print/1543-5326 online DOI: 10.1080/10509200490273071 A Star Has Died: Affect and Stardom in a Domestic Melodrama ANNE MOREY Until relatively recently, it has been fashionable to read Douglas Sirk as ridiculing popular culture through his manipulation of it. In other words, critics tell us, to be moved by a Sirk film is to have missed the critical boat—because, as Paul Willemen has noted, the director himself offers up a textual performance that is anything but sincere. Christine Gledhill and Walter Metz have attempted to rescue the duped audience from this critical opprobrium. Gledhill argues that Sirk appropriates the conventions of the woman’s film, in which female concerns should be and have been central, to reorder the narrative elements into a story of the absent patriarch. Similarly, Metz recuperates this possibly duped audience of female readers/viewers by reevaluating the (female) authors of the texts that Sirk so obsessively remakes, arguing that many of the signifiers of “auteurship” usually granted to Sirk are already on display in the original works (12). Like Gledhill and Metz, I seek to demonstrate that Sirk is more than a parodist. This article compares Sirk’s Imitation of Life (1959) to David O. Selznick and William Wellman’s A Star Is Born (1937) in order to explore a characteristically Sirkian narrative strategy: the later film does not amuse itself at its predecessor’s expense so much as it inverts the message. -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

1 Genre Films: OLLI: Spring 2021: Week 5: Melodrama: Douglas Sirk

1 Genre Films: OLLI: Spring 2021: week 5: Melodrama: Douglas Sirk: King of Hollywood Melodrama IMITATION OF LIFE: 1933: novel: Fannie Hurst / 1934: film: director: John Stahl: white mother & daughter: Bea & Jessie Pullman black mother & daughter: Delilah & Peola Johnson both book and 1934 film straightforward & unambiguous in attitudes re: race, motherhood, emotional centers for story title: refers to daughter trying to "pass" for white: imitating white life; Sirk subverts this: Stahl version: 1934 Sirk version: 1959 "invisible" storytelling techniques techniques that call attention to themselves story of 2 mothers: complementary issue of motherhood: as clouded as race: both black & white mothers exposed: clichés: excessive love/excessive egotism present mother/absent mother nurturer/sex object bald opposition becomes ironic versions of "good" mom opening scene: in the home: opening scene: in public: Coney Island: Bea caring for Jessie ("quack- Lora has lost Susie quack") Bea's success due to Delilah's recipe: Lora's success due to her beauty: partnership between 2 women she's a sexual object: actress Annie not part of it man enters Bea's life: after her success man enters Lora's life: in 1st scene: he's conscious reminder of her choice: between career & love Sirk's version deals with issues of: 1. race: but in 1950s America: issue much more complex than in 1930s: Rosa Parks, Brown v. Board of Education, etc.; Civil Rights issues not resolved Sirk avoids direct reference to Civil Rights Movement: but it's there under surface: Sarah Jane's -

Starters Mains Desserts

STARTERS 2 COURSES £25.95 | 3 COURSES £29.95 SEASONAL SOUP OF THE DAY(V) soft bread roll, house churned butter CORNFED CHICKEN, SOFT HERB & PINK PEPPERCORN TERRINE beer pickled shallots, toast SMOKED HAM CROQUETTE house piccalilli, mustard pickle aioli BEETROOT BARLEY RISOTTO(V) black pepper goats cheese balls, spelt granola MAINS BUTTER BRAISED CAULIFLOWER STEAK(VE) romesco sauce, cherry tomato salad, gremolata BREAST OF CORN-FED CHICKEN isle of mull & anchovy emulsion, grilled gem, pancetta crumb 6OZ STEAK BURGER bacon jam, monteray jack, tomato, lettuce on a brioche bun, with fries BRAISED BLACK FACE LAMB PIE potato and black pudding terrine & lamb jus FISH & CHIPS tarragon aioli, tartare sauce 8OZ 50 DAY AGED BEEF RIBEYE (£8 SUPPLEMENT) fries, grilled plum tomato & flat cap mushroom DESSERTS TONKA BEAN CRÈME BRÛLÉE almond biscuits STICKY DATE & GINGER PUDDING toffee sauce, vanilla ice cream PEACH & RASPBERRY PAVLOVA(GF) raspberry sorbet SELECTION OF ARRAN DAIRY ICE CREAMS(GF) CHEFS SELECTION OF SCOTTISH CHEESES & CONDIMENTS (£3 SUPPLEMENT) (V) Vegetarian (VE) Vegan (GF) Gluten Free A number of our dishes can be adapted to cater for your food allergies and deitary requirements. Market Menu Market Please speak to your server who will be able to advise. Full allergy information for each dish is available upon request. w STARTERS MAINS SEASONAL SOUP BUTTER POACHED OF THE DAY (V) LOIN OF PORK served with soft bread roll, house WITH PORK churned butter & SHRIMP FAGGOT £5.50 with black pudding & potato terrine, apple & herb relish, celeriac -

To Start from the Garden Jerusalem Artichoke Veloute Vegan Option Available Truffled Arancini Wild Garlic Yarg Pesto Roasted Hazelnut £9

12-14:30 ~ 18:30-21 Our aim at Talland Bay Hotel is to utilise the very best from local produce. We operate in a Nose to Tail way of cooking, using sustainable fish, meat & vegetables with the ever- changing seasons. From The Farm – Philip Warren Butchery – Bodmin Moor to Exemoor From The Sea – Simply Fish – Looe & Cornwall From The Garden – Tamar Fresh – Saltash From The Creamery – Roddas Creamery - Redruth To Start From The Garden Jerusalem Artichoke Veloute Vegan Option Available Truffled Arancini Wild Garlic Yarg Pesto Roasted Hazelnut £9 Truffled Egg Yolk Ravioli Morels Miss Muffet Tarragon £11 From The Farm Pressed Smoked Ham Hock & Roast Chicken Terrine Liver Parfait Pickled Rhubarb Sour Dough £9 From The Sea Cornish Mackerel Cornish Scallops Smoked Mackerel Scotch Egg Caramelised Cauliflower Curry Scorched Fillet Beetroot Oil Lime Vanilla Cashew Buttermilk Horseradish £13 £12 For Main From The Sea Dover Sole Grenobloise From The Garden Confit Potato Chips Cucumber Seasonal Greens Grenobloise Butter Wild Mushroom Gnocchi £24 Cornish Nanny Roasted Cauliflower Roasted Pollock Charred Onion Broth Brown Shrimp Wild Mushroom £18 Ketchup Sarladaise Potato Lovage £19 New Season Wild Garlic Risotto Vegan Option Available Day Boat Fish & Chips Chestnut Mushroom Goats Curd Lushingtons Beer Batter Crispy Shallots Triple Cooked Chips Marrow £18 Fat Mushy Peas Tartare Sauce Batter Bits £18 From The Farm West Country Glazed Brisket West Country Lamb Pomme Puree Honey & Ginger Roasted Rump Faggot Pie Carrots Scorched -

Selected Criticism, Jeffery Jullich

Selected Criticism Jeffrey Jullich Publishing the Unpublishable 017 ©2007 /ubu editions Series Editor: Kenneth Goldsmith /ubu editions www.ubu.com 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Aaron Shurin: The Paradise of Forms 5 Standard Schaefer: Nova 9 Leslie Scalapino: New Time 12 Cole Swensen: Try 15 Susan Howe / Susan Bee: Bed Hangings I 17 Graham Foust: As in Every Deafness 24 Rae Armantrout: Up to Speed 25 Michael Scharf: Verité 26 Drew Gardner: Sugar Pill 29 SELECTED BUFFALO POETICS LISTSERV POSTS Class and poetry 39 Lyn Hejinian's 'deen' 41 D=E=E=N 42 A Barnard report: Hannah Weiner 45 Spaced-out 47 Questions on a HOW TO value 49 Submission crucible 52 $3.50 Summer vacation in Scandinavia 54 Alternative 56 Farm implements and rutabagas in a landscape 58 Polyverse by Lee Ann Brown 60 Cut-ups and homosexualization of the New York School (I) 63 Cut-ups and homosexualization of the New York School (II) 65 Simon Perchik 67 Marilyn Monroe - the Emma Lazarus of her day 69 classical meter in contemporary "free verse" poetry Meter Anthology Cola 70 New Formalist Language Poetry 72 Language Prosody - ex. 2: Dochmiacs 74 Language Prosody - ex. 3: hypodochmiacs in Susan Howe's Pierce Arrow 76 Language Prosody - ex. 4: adonics 78 Language Prosody - ex. 5: H.D., Helen in Egypt 85 Timothy McVeigh's face 89 Hannah Weiner's hallucinations and schizophrenia in poetry Hannah's visions 93 Hannah's visions - Barrett Watten's 'Autobiography Simplex' 95 Hannah's visions 99 eulogy for Tove Janesson (Finnish author of the Mummintroll books) 103 3 creative writing pedagogy 104 -

Sit Down Menus

WN DO SIT US MEN No Frills Banqueting Menu Soup Ideas £22.50pp Carrot, red chilli and cumin Starters (choose one for your party) with fresh coriander oil All served with freshly baked petite pain Seasonal soup of your choice Leek and potato with crème fraiche Warm caramelised red onion and blue cheese tartlet with dressed baby leaves Chef ’s chicken liver pâté served with melba toast Broccoli and Stilton Creamy garlic mushrooms with black pepper croutons Traditional prawn cocktail in a Marie Rose sauce Selection of fruit sorbets Lentil soup with crispy bacon Mains (choose one for your party) Tomato, garlic and basil Traditional roast beef, Yorkshire Pudding and all the trimmings with fresh homemade pesto Traditional roast chicken, stuffing, chipolata and bread sauce Roast Mediterranean vegetable tart with toasted goats’ cheese Green pea and ham Baked cod fillet with citrus fruit hollandaise with pea shoots Chicken breast with a button mushroom and white wine sauce Desserts (choose one for your party) Asparagus soup with crisp parma ham* Sticky toffee pudding with vanilla bean ice cream and Chantilly cream Vanilla scented cheesecake with forest fruit berries Wild mushroom with truffle oil* Homemade dark chocolate marquis with a white chocolate sail Caramelised lemon tart, and lemon coulis *£1.00pp supplement Luxury ice cream Gourmet Party Menu £35.00pp Starters (choose 3 to offer your guests - pre-order required) All served with artisan bread rolls Homemade tomato and fresh basil soup OR soup of your choice Sweet trio of melon with compôte