Read the Preface and the Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

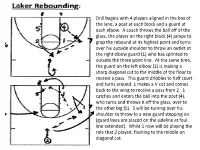

Drill Begins with 4 Players Aligned in the Box of the Lane, a Post at Each Block and a Guard at Each Elbow

Drill begins with 4 players aligned in the box of the lane, a post at each block and a guard at each elbow. A coach throws the ball off of the glass, the player on the right block (4) jumps to grap the rebound at its highest point and turns over his outside shoulder to throw an outlet ot the right elbow guard (1) who has sprinted to outside the three point line. At the same time, the guard on the left elbow (2) is making a sharp diagonal cut to the middle of the floor to receive a pass. This guard dribbles to half court and turns around. 1 makes a V cut and comes back to the wing to receive a pass from 2. 1 catches and enters the ball into the post (4), who turns and throws it off the glass, over to the other big (5). 5 will be turning over his shoulder to throw to a new guard stepping on (guard lines are placed on the sideline at foul line extended). While 1 now will be playing the role that 2 played, flashing to the middle on diagonal cut. Divide the team into three teams (A,B , and C) and have them line up as shown. The first player in line steps up and A has the ball. ‘A’ shoots a three. The ball is “live”, regardless of whether or not the shot is missed or made. (On a make the three doesn’t count). The game then becomes 1 on 1 on 1. With the player who grabbed the rebound being the one on offense. -

Intramural Sports Floor Hockey Rules

Princeton University Intramural Sports Floor Hockey Rules I. EQUIPMENT/UNIFORM/ELIGIBILITY a. All players must present their Princeton University ID in order to participate. b. The Intramural Department will provide sticks and balls. c. Players may wear gloves/mittens for hand protection. d. Each player must wear non-marking athletic shoes. e. Players may not wear hats with brims or jewelry during play. f. Goalies MUST wear a regulation catcher’s mask/goalie mask and chest protector, which are provided, if a goalie chooses to wear their own mask – it must be inspected by IM Supervisor before game begins. g. Goalies may wear a baseball glove on their non-stick hand and leg pads. h. All players must play in at least ONE regular season game in order to be eligible for playoffs. i. Players can only play for ONE Open/Women’s and/or ONE CoRec Team. j. Men’s and Women’s varsity Ice Hockey players and varsity Field Hockey players are not eligible. k. Only 2 Ice Hockey/Field Hockey Club players or 2 Junior Varsity players (or combination of the 2) are eligible to be on a team’s roster. II. NUMBER OF PLAYERS/GAME TIME/FORFEIT PENALTY a. Teams consist of 5 players on the floor at one time, four offensive players and a goalie. b. A minimum of 4 players is required to start and continue a game. c. For CoRec, the gender ratio is 3:2 with five players; and 2:2 with four players. d. A team that fails to have 4 players within 10 minutes after the start time of the game will forfeit/default the game. -

Praise for Everyone Hates a Ball Hog but They All Love a Scorer

Praise for Everyone Hates A Ball Hog But They All Love A Scorer “Coach Godwin's book offers a complete guide to being a team player, both on and off the court.” --Stack Magazine “Coach Godwin's book gives you insight on how to improve your game. If you are a young player trying to get better, this is a book I would recommend reading immediately.” --Clifford Warren, Head Coach Jacksonville University “Coach Godwin explains in understandable terms how to improve your game. A must have for any young player hoping to get to the next level.” --Khalid Salaam, Senior Editor, SLAM Magazine “I wish that I had this book when I was 16. I would have been a different and better player. Well done.” --Jeff Haefner, Co-owner, BreakthroughBasketball.com “The entire book is filled with gems, some new, some revised and some borrowed, but if you want to read one book this year on how to become a better scorer this is the book.” --Jerome Green, Hoopmasters.org “Detailed instruction on how to score, preaching that the game is more mental than physical. Good reading for the young set, who might put down that joystick for a few hours.” --CharlotteObserver.com Everyone Hates A Ball Hog But They All Love A Scorer ____________________________________________ The Complete Guide to Scoring Points On and Off the Basketball Court Coach Koran Godwin This book is dedicated to my mother, Rhonda who supported me every step of the way. Thanks for planting the seeds of success in my life. I am forever grateful. -

Referee.Com Basketball Case Play of the Day Day 51

Referee.com Basketball Case Play of the Day Day 51- Disqualified Player PLAY A1 is called for a common foul, and it is A5’s fifth personal foul. A1 properly leaves the game after receiving this fifth and disqualifying foul. Later in the game, A1 reports to the table to check back into the game. Neither the official scorer nor the officials recognize that A1 had previously been disqualified, and they allow A1 to re-enter the game. After a few minutes have run off the game clock and (a) after A1 had checked back out of the game, or (b) while A1 is still in the game, the scorer notifies the officials that A1 had been disqualified, but participated again in the game. What is the result? RULING Participating after being disqualified results in a technical foul. The technical foul is only penalized if it is discovered while being violated. Therefore, in (a), since A1 was no longer in the game, no technical foul shall be assessed. In (b), a technical foul shall be charged directly to team A’s head coach, A1 shall be removed from the game, team B shall receive two free throws and a division line throw in (10-6-3, 10.6.3). Day 50- Colors of Team Apparel PLAY Team A is wearing blue jerseys with gold trim. During pregame warmups, the officials notice A1 is wearing a black undershirt, blue wristbands and gold tights. Are those colors legal? RULING The color of the undershirt must be a single color similar to the torso of the game jersey, and thus a black undershirt is not legal. -

Fiba Glossary.Pdf

Glossary Basketball Glossary A Advance step: A step in which the defender's lead foot steps toward their man, and her back foot slides forward. Assist: A pass thrown to a player who immediately scores. B Backcourt: The half of the court a team is defending. The opposite of the frontcourt. Also used to describe parts of a team: backcourt = all guards (front court= all forwards and centers) Back cut: See cuts, Backdoor cut Backdoor cut: See cuts Back screen: See Screens Ball fake: A sudden movement by the player with the ball intended to cause the defender to move in one direction, allowing the passer to pass in another direction. Also called "pass fake." Ball reversal: Passing the ball from one side of the court to the other. Ball screen: See Screens Ball side: The half of the court (if the court is divided lengthwise) that the ball is on. Also called the "strong side." The opposite of the help side. Banana cut: See cuts Bank shot: A shot that hits the backboard before hitting the rim or going through the net. Baseball pass: A one-handed pass thrown like a baseball. Baseline: The line that marks the playing boundary at each end of the court. Also called the "end line." Baseline out-of-bounds play: The play used to return the ball to the court from outside the baseline along the opponent's basket. Basket cut: See cuts. Blindside screen: See Backscreen Glossary Block: (1) A violation in which a defender steps in front of a dribbler but is still moving when they collide. -

Analyzing the Influence of Player Tracking Statistics on Winning Basketball Teams

Analyzing the Influence of Player Tracking Statistics on Winning Basketball Teams Igor Stan čin * and Alan Jovi ć* * University of Zagreb Faculty of Electrical Engineering and Computing / Department of Electronics, Microelectronics, Computer and Intelligent Systems, Unska 3, 10 000 Zagreb, Croatia [email protected], [email protected] Abstract - Basketball player tracking and hustle statistics year at the Olympic games, by winning a gold medal in the became available since 2013-2014 season from National majority of cases. Off the court, there are specialized Basketball Association (NBA), USA. These statistics provided personnel who try to improve each segment of the game, us with more detailed information about the played games. e.g. doctors, psychologists, basketball experts and scouts. In this paper, we analyze statistically significant differences One of the most interesting facts is that the teams in the in these recent statistical categories between winning and losing teams. The main goal is to identify the most significant league, and the league itself, have expert teams for data differences and thus obtain new insight about what it usually analysis that provide them with valuable information about may take to be a winner. The analysis is done on three every segment of the game. There are a few teams who different scales: marking a winner in each game as a winning make all of their decisions exclusively based on advanced team, marking teams with 50 or more wins at the end of the analysis of statistics. Few years ago, this part of season as a winning team, and marking teams with 50 or organization became even more important, because NBA more wins in a season, but considering only their winning invested into a computer vision system that collects games, as a winning team. -

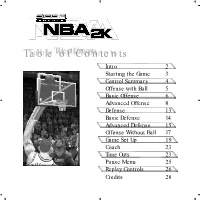

NBA 2K Is a One-To Four-Player Game

2KBasketball_Manual 2/25/00 11:46 AM Page 1 TTableableT ableof of ContentsContyentsContents Intro 2 Starting the Game 3 Control Summary 4 Offense with Ball 5 Basic Offense 6 Advanced Offense 8 Defense 13 Basic Defense 14 Advanced Defense 15 Offense Without Ball 17 Game Set Up 19 Coach 23 Time Outs 23 Pause Menu 25 Replay Controls 26 Credits 28 2KBasketball_Manual 2/25/00 11:46 AM Page 2 STARTING THE GAME Blood rushes to your head as you Note: Sega Sports™ NBA 2K is a one-to four-player game. get up from the final timeout. Purchase additional controllers (sold sepa- rately) to play with two or more people. The crowd is deafening, but you block it out, Before turning the Dreamcast power because quite simply - it’s crunchtime, and you want the rock. ON, connect the controller(s) or other peripheral equipment into the control ports of the Dreamcast. 6 seconds left in the game, To return to the title screen at any point dur- ing game play, simultaneously press and and you’re down 1. You come off the pick and grab the inbound pass, hold the A , B, X, Y and Start Buttons. Power Button Open Button and immediately you’re double-teamed. This will cause the Dreamcast to soft-reset Port A Port C the software and display the title screen. 3 Fake left with a quick step, but spin right and sprint down the sideline. Port B Port D When using a Jump Pack™ (sold separate- ly), insert it into Expansion Socket 2 of the You take a look at the clock and it’s down to 3. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Who's Got Next? Social Integration at a Public Park Basketball Court Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2r78z50v Author DeLand, Michael Francis Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Who’s Got Next? Social Integration at a Public Park Basketball Court A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology by Michael Francis DeLand 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Who’s Got Next? Social Integration at a Public Park Basketball Court by Michael Francis DeLand Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Jack Katz, Chair This dissertation examines the ongoing formation of a public park as a particular type of public place. Based on four years of in-depth participant observation and historical and archival research I show how a pickup basketball scene has come to thrive at Ocean View Park (OVP) in Santa Monica California. I treat pickup basketball as a case of public place integration which pulls men out of diverse biographical trajectories into regular, intense, and emotional interactions with one another. Many of the men who regularly play at Ocean View Park hold the park in common, if very little else in their lives. Empirical chapters examine the contingencies of the park’s historical formation and the basketball scene’s contemporary continuation. Through comparative historical research I show how Ocean View Park was created as a “hidden gem” within its local urban ecology. -

The “Dribble, Drive, Motion” Offense

november / december 2008 / december november 35 FOR basketball enthusiasts everywhere enthusiasts basketball FOR FIBA ASSIST MAGAZINE FIBA ASSIST assist Slobodan klipa u20 serbian men’s vance walberg secondary fastbreak steve smith the oak hill “32 series” the “dribble, antonio pagano the entertainment factor drive, motion” one-on-one chuck daly offense tables of contents 2009-10 FIBA CALENDAR COACHES 2009 FUNDAMENTALS AND YOUTH BASKETBALL The Oak Hill "32 Series" 4 June 2009 07 - 20.06 EuroBasket Women by Steve Smith in Latvia July 2009 U20 Serbian Men's Secondary Fastbreak 8 02 - 12.07 FIBA U19 World Championship for Men in by Slobodan Klipa Auckland (NZL) 23.07 -02.08 FIBA U19 World Championship for Women in Bangkok (THA) Drills After the Warm Up - Part II 14 FIBA ASSIST MAgAZINE september 2009 by Pepu Hernandez IS A PUBLICATION OF FIBA International Basketball Federation 07 - 20.09 EuroBasket Men in Poland 51 – 53, Avenue Louis Casaï 23 - 27.09 FIBA Americas CH-1216 Cointrin/Geneva Switzerland Championship for Women OFFENSE Tel. +41-22-545.0000, Fax +41-22-545.0099 in Mato Groso (BRA) www.fiba.com / e-mail: [email protected] 24 - 03.10 FIBA Africa The "Dribble, Drive, Motion" Offense 20 Championship for Women IN collaboration wITH Giganti del Basket, by Vance Walberg Cantelli Editore, Italy in Bamako (MLI) Partner WABC (World Association of Basketball Coaches), Dusan Ivkovic President 2010 HOOP MARKET July 2010 The New Frontier of the Offense 28 Editor-in-Chief 02 - 11.07 FIBA U17 World Giorgio Gandolfi Championship for Men by Raffaele Imbrogno (site tbd) 16 - 26.07 FIBA U17 World Editorial Office: Cantelli Editore, Championship for Women V. -

The Hot Hand Phenomenon in Basketball Revisited

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 8-2018 The otH Hand Phenomenon in Basketball Revisited Alexander T. Dahlstrom Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Recommended Citation Dahlstrom, Alexander T., "The otH Hand Phenomenon in Basketball Revisited" (2018). All Theses. 2952. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/2952 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HOT HAND PHENOMENON IN BASKETBALL REVISITED A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Economics by Alexander T. Dahlstrom August 2018 Accepted by: Dr. Raymond Sauer, Committee Chair Dr. Scott Templeton Dr. Robert Fleck ABSTRACT The focus of this paper is to summarize the economic literature of the hot hand phenomenon in basketball while adding in another study of my own. By using recent NBA statistical data, I will show the advancement and evolution of this widely held public belief that a certain number of makes or misses can alter the chances of the next attempt’s success or failure. I start by recreating part of Gilovich, Valone, and Tversky’s (1985) experiments with a larger set of data and finish by introducing Miller and Sanjurjo’s fix to their method’s biases(2015). The major finding is when a three and an eight percentage point correction for the bias from Miller and Sanjurjo’s calculations are applied to my data set as well as many other studies, that a hot hand effect starts to surface more frequently. -

Taco Bell, Pizza Hut to Replace Sbarro in Fall

The Independent Newspaper Serving Notre Dame and Saint Mary’s Volume 45: Issue 129 Wednesday, April 25, 2012 Ndsmcobserver.com Taco Bell, Pizza Hut to replace Sbarro in fall By KRISTEN DURBIN said. News Editor Prentkowski said the deci- sion to replace Sbarro has When students return to been deliberated for the past campus for the fall 2012 se- three years due to the ap- mester, they will have two proaching expiration of the new fast-food dining options franchise’s contract and its to choose from in the Huddle decline in business. Food Court in LaFortune Stu- “Over the last few years, we dent Center. saw Sbarro’s business decline, On Monday, Food Services and the overall student satis- announced its plans to open faction with and preference Taco Bell and Pizza Hut fran- for Sbarro as a brand declined chise concepts in the current as well according to surveys, location of Sbarro this fall. so we took the upcoming expi- The addition of the restau- ration of the franchise agree- rants will be the first fran- ment as a good opportunity chise change in the Huddle to take a look at our alterna- since 2003, Food Services di- tives,” Prentkowski said. rector David Prentkowski said. Jim LaBella, the general “It’s been 10 years since manager of the Huddle, said SARAH O’CONNOR/The Observer Sbarro went in, so it’s time for A student browses his options at Sbarro in the LaFortune Student Center on Tuesday. a change. I’m excited for it,” he see SBARRO/page 3 Pizza Hut and Taco Bell will take over the space in the fall. -

Coaching Made Easy

coaching made easy Training Drills 1 | P a g e The National Coaching and Accreditation Scheme (NCAS) was established in 1978 with the primary aim of up-grading and expanding coaching expertise across a wide range of sports. Basketball Australia has embraced this scheme since its inception. This Resource Manual is a substantial revision on previous editions and supports the new NCAS structure for Basketball Australia’s Club Coach Level (equivalent to the previous NCAS Level1) many thanks to the numerous coaches who have been kind enough to have input into these resources over the years and in the current upgrade. The manual remains the basis of Basketball Australia’s NCAS Club Coach course however has been produced in separate booklets to make it easier for coaches to identify specific information they are seeking This resource is not designed to have all coaches around Australia doing the same thing, rather it is to allow coaches at all levels to perform more effectively and constructively. The application of knowledge remains flexible according to the talent and ability of the individual coach and the athletes they are working with. Introduction Australia has a proud history in basketball and in 2004 was ranked 3rd amongst all nations. This success is due in no small way to the tireless work of coaches throughout the country, from “learn to play” programs right through to the Boomers and Opals. The National Coaching and Accreditation Scheme (NCAS) was established in 1978 with the primary aim of up-grading and expanding coaching expertise across a wide range of sports.