The Hot Hand Phenomenon in Basketball Revisited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Volume 100 : 25Th October 2015

Read Volume 100 : 25th October 2015 Forum for Multidisciplinary Thinking !1 Read Volume 100 : 25th October 2015 Contact Page 3: Gamblers, Scientists and the Mysterious Hot Hand By George Johnsonoct Page 8: Daniel Kahneman on Intuition and the Outside View By Elliot Turner Page 13: Metaphors Are Us: War, murder, music, art. We would have none without metaphor By Robert Sapolsky Forum for Multidisciplinary Thinking !2 Read Volume 100 : 25th October 2015 Gamblers, Scientists and the Mysterious Hot Hand By George Johnsonoct 17 October 2015 IN the opening act of Tom Stoppard’s play “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead,” the two characters are passing the time by betting on the outcome of a coin toss. Guildenstern retrieves a gold piece from his bag and flips it in the air. “Heads,” Rosencrantz announces as he adds the coin to his growing collection. Guil, as he’s called for short, flips another coin. Heads. And another. Heads again. Seventy-seven heads later, as his satchel becomes emptier and emptier, he wonders: Has there been a breakdown in the laws of probability? Are supernatural forces intervening? Have he and his friend become stuck in time, reliving the same random coin flip again and again? Eighty-five heads, 89… Surely his losing streak is about to end. Psychologists who study how the human mind responds to randomness call this the gambler’s fallacy — the belief that on some cosmic plane a run of bad luck creates an imbalance that must ultimately be corrected, a pressure that must be relieved. After several bad rolls, surely the dice are primed to land in a more advantageous way. -

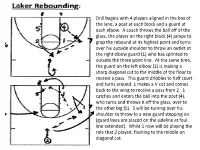

Drill Begins with 4 Players Aligned in the Box of the Lane, a Post at Each Block and a Guard at Each Elbow

Drill begins with 4 players aligned in the box of the lane, a post at each block and a guard at each elbow. A coach throws the ball off of the glass, the player on the right block (4) jumps to grap the rebound at its highest point and turns over his outside shoulder to throw an outlet ot the right elbow guard (1) who has sprinted to outside the three point line. At the same time, the guard on the left elbow (2) is making a sharp diagonal cut to the middle of the floor to receive a pass. This guard dribbles to half court and turns around. 1 makes a V cut and comes back to the wing to receive a pass from 2. 1 catches and enters the ball into the post (4), who turns and throws it off the glass, over to the other big (5). 5 will be turning over his shoulder to throw to a new guard stepping on (guard lines are placed on the sideline at foul line extended). While 1 now will be playing the role that 2 played, flashing to the middle on diagonal cut. Divide the team into three teams (A,B , and C) and have them line up as shown. The first player in line steps up and A has the ball. ‘A’ shoots a three. The ball is “live”, regardless of whether or not the shot is missed or made. (On a make the three doesn’t count). The game then becomes 1 on 1 on 1. With the player who grabbed the rebound being the one on offense. -

Uncertainty in the Hot Hand Fallacy: Detecting Streaky Alternatives in Random Bernoulli Sequences

UNCERTAINTY IN THE HOT HAND FALLACY: DETECTING STREAKY ALTERNATIVES IN RANDOM BERNOULLI SEQUENCES By David M. Ritzwoller Joseph P. Romano Technical Report No. 2019-05 August 2019 Department of Statistics STANFORD UNIVERSITY Stanford, California 94305-4065 UNCERTAINTY IN THE HOT HAND FALLACY: DETECTING STREAKY ALTERNATIVES IN RANDOM BERNOULLI SEQUENCES By David M. Ritzwoller Joseph P. Romano Stanford University Technical Report No. 2019-05 August 2019 Department of Statistics STANFORD UNIVERSITY Stanford, California 94305-4065 http://statistics.stanford.edu Uncertainty in the Hot Hand Fallacy: Detecting Streaky Alternatives in Random Bernoulli Sequences David M. Ritzwoller, Stanford University∗ Joseph P. Romano, Stanford University August 22, 2019 Abstract We study a class of tests of the randomness of Bernoulli sequences and their application to analyses of the human tendency to perceive streaks as overly representative of positive dependence—the hot hand fallacy. In particular, we study tests of randomness (i.e., that tri- als are i.i.d.) based on test statistics that compare the proportion of successes that directly follow k consecutive successes with either the overall proportion of successes or the pro- portion of successes that directly follow k consecutive failures. We derive the asymptotic distributions of these test statistics and their permutation distributions under randomness and under general models of streakiness, which allows us to evaluate their local asymp- totic power. The results are applied to revisit tests of the hot hand fallacy implemented on data from a basketball shooting experiment, whose conclusions are disputed by Gilovich, Vallone, and Tversky (1985) and Miller and Sanjurjo (2018a). We establish that the tests are insufficiently powered to distinguish randomness from alternatives consistent with the variation in NBA shooting percentages. -

Intramural Sports Floor Hockey Rules

Princeton University Intramural Sports Floor Hockey Rules I. EQUIPMENT/UNIFORM/ELIGIBILITY a. All players must present their Princeton University ID in order to participate. b. The Intramural Department will provide sticks and balls. c. Players may wear gloves/mittens for hand protection. d. Each player must wear non-marking athletic shoes. e. Players may not wear hats with brims or jewelry during play. f. Goalies MUST wear a regulation catcher’s mask/goalie mask and chest protector, which are provided, if a goalie chooses to wear their own mask – it must be inspected by IM Supervisor before game begins. g. Goalies may wear a baseball glove on their non-stick hand and leg pads. h. All players must play in at least ONE regular season game in order to be eligible for playoffs. i. Players can only play for ONE Open/Women’s and/or ONE CoRec Team. j. Men’s and Women’s varsity Ice Hockey players and varsity Field Hockey players are not eligible. k. Only 2 Ice Hockey/Field Hockey Club players or 2 Junior Varsity players (or combination of the 2) are eligible to be on a team’s roster. II. NUMBER OF PLAYERS/GAME TIME/FORFEIT PENALTY a. Teams consist of 5 players on the floor at one time, four offensive players and a goalie. b. A minimum of 4 players is required to start and continue a game. c. For CoRec, the gender ratio is 3:2 with five players; and 2:2 with four players. d. A team that fails to have 4 players within 10 minutes after the start time of the game will forfeit/default the game. -

Praise for Everyone Hates a Ball Hog but They All Love a Scorer

Praise for Everyone Hates A Ball Hog But They All Love A Scorer “Coach Godwin's book offers a complete guide to being a team player, both on and off the court.” --Stack Magazine “Coach Godwin's book gives you insight on how to improve your game. If you are a young player trying to get better, this is a book I would recommend reading immediately.” --Clifford Warren, Head Coach Jacksonville University “Coach Godwin explains in understandable terms how to improve your game. A must have for any young player hoping to get to the next level.” --Khalid Salaam, Senior Editor, SLAM Magazine “I wish that I had this book when I was 16. I would have been a different and better player. Well done.” --Jeff Haefner, Co-owner, BreakthroughBasketball.com “The entire book is filled with gems, some new, some revised and some borrowed, but if you want to read one book this year on how to become a better scorer this is the book.” --Jerome Green, Hoopmasters.org “Detailed instruction on how to score, preaching that the game is more mental than physical. Good reading for the young set, who might put down that joystick for a few hours.” --CharlotteObserver.com Everyone Hates A Ball Hog But They All Love A Scorer ____________________________________________ The Complete Guide to Scoring Points On and Off the Basketball Court Coach Koran Godwin This book is dedicated to my mother, Rhonda who supported me every step of the way. Thanks for planting the seeds of success in my life. I am forever grateful. -

Surprised by the Gambler's and Hot Hand Fallacies?

Surprised by the Gambler's and Hot Hand Fallacies? A Truth in the Law of Small Numbers Joshua B. Miller and Adam Sanjurjo ∗yz September 24, 2015 Abstract We find a subtle but substantial bias in a standard measure of the conditional dependence of present outcomes on streaks of past outcomes in sequential data. The mechanism is a form of selection bias, which leads the empirical probability (i.e. relative frequency) to underestimate the true probability of a given outcome, when conditioning on prior outcomes of the same kind. The biased measure has been used prominently in the literature that investigates incorrect beliefs in sequential decision making|most notably the Gambler's Fallacy and the Hot Hand Fallacy. Upon correcting for the bias, the conclusions of some prominent studies in the literature are reversed. The bias also provides a structural explanation of why the belief in the law of small numbers persists, as repeated experience with finite sequences can only reinforce these beliefs, on average. JEL Classification Numbers: C12; C14; C18;C19; C91; D03; G02. Keywords: Law of Small Numbers; Alternation Bias; Negative Recency Bias; Gambler's Fal- lacy; Hot Hand Fallacy; Hot Hand Effect; Sequential Decision Making; Sequential Data; Selection Bias; Finite Sample Bias; Small Sample Bias. ∗Miller: Department of Decision Sciences and IGIER, Bocconi University, Sanjurjo: Fundamentos del An´alisisEcon´omico, Universidad de Alicante. Financial support from the Department of Decision Sciences at Bocconi University, and the Spanish Ministry of Economics and Competitiveness under project ECO2012-34928 is gratefully acknowledged. yBoth authors contributed equally, with names listed in alphabetical order. -

Infographic I.10

The Digital Health Revolution: Leaving No One Behind The global AI in healthcare market is growing fast, with an expected increase from $4.9 billion in 2020 to $45.2 billion by 2026. There are new solutions introduced every day that address all areas: from clinical care and diagnosis, to remote patient monitoring to EHR support, and beyond. But, AI is still relatively new to the industry, and it can be difficult to determine which solutions can actually make a difference in care delivery and business operations. 59 Jan 2021 % of Americans believe returning Jan-June 2019 to pre-coronavirus life poses a risk to health and well being. 11 41 % % ...expect it will take at least 6 The pandemic has greatly increased the 65 months before things get number of US adults reporting depression % back to normal (updated April and/or anxiety.5 2021).4 Up to of consumers now interested in telehealth going forward. $250B 76 57% of providers view telehealth more of current US healthcare spend % favorably than they did before COVID-19.7 could potentially be virtualized.6 The dramatic increase in of Medicare primary care visits the conducted through 90% $3.5T telehealth has shown longevity, with rates in annual U.S. health expenditures are for people with chronic and mental health conditions. since April 2020 0.1 43.5 leveling off % % Most of these can be prevented by simple around 30%.8 lifestyle changes and regular health screenings9 Feb. 2020 Apr. 2020 OCCAM’S RAZOR • CONJUNCTION FALLACY • DELMORE EFFECT • LAW OF TRIVIALITY • COGNITIVE FLUENCY • BELIEF BIAS • INFORMATION BIAS Digital health ecosystems are transforming• AMBIGUITY BIAS • STATUS medicineQUO BIAS • SOCIAL COMPARISONfrom BIASa rea• DECOYctive EFFECT • REACTANCEdiscipline, • REVERSE PSYCHOLOGY • SYSTEM JUSTIFICATION • BACKFIRE EFFECT • ENDOWMENT EFFECT • PROCESSING DIFFICULTY EFFECT • PSEUDOCERTAINTY EFFECT • DISPOSITION becoming precise, preventive,EFFECT • ZERO-RISK personalized, BIAS • UNIT BIAS • IKEA EFFECT and • LOSS AVERSION participatory. -

Gambler's Fallacy, Hot Hand Belief, and the Time of Patterns

Judgment and Decision Making, Vol. 5, No. 2, April 2010, pp. 124–132 Gambler’s fallacy, hot hand belief, and the time of patterns Yanlong Sun∗ and Hongbin Wang University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston Abstract The gambler’s fallacy and the hot hand belief have been classified as two exemplars of human misperceptions of random sequential events. This article examines the times of pattern occurrences where a fair or biased coin is tossed repeatedly. We demonstrate that, due to different pattern composition, two different statistics (mean time and waiting time) can arise from the same independent Bernoulli trials. When the coin is fair, the mean time is equal for all patterns of the same length but the waiting time is the longest for streak patterns. When the coin is biased, both mean time and waiting time change more rapidly with the probability of heads for a streak pattern than for a non-streak pattern. These facts might provide a new insight for understanding why people view streak patterns as rare and remarkable. The statistics of waiting time may not justify the prediction by the gambler’s fallacy, but paying attention to streaks in the hot hand belief appears to be meaningful in detecting the changes in the underlying process. Keywords: gambler’s fallacy; hot hand belief; heuristics; mean time; waiting time. 1 Introduction is the representativeness heuristic, which attributes both the gambler’s fallacy and the hot hand belief to a false The gambler’s fallacy and the hot hand belief have been belief of the “law of small numbers” (Gilovich, et al., classified as two exemplars of human misperceptions of 1985; Tversky & Kahneman, 1971). -

Referee.Com Basketball Case Play of the Day Day 51

Referee.com Basketball Case Play of the Day Day 51- Disqualified Player PLAY A1 is called for a common foul, and it is A5’s fifth personal foul. A1 properly leaves the game after receiving this fifth and disqualifying foul. Later in the game, A1 reports to the table to check back into the game. Neither the official scorer nor the officials recognize that A1 had previously been disqualified, and they allow A1 to re-enter the game. After a few minutes have run off the game clock and (a) after A1 had checked back out of the game, or (b) while A1 is still in the game, the scorer notifies the officials that A1 had been disqualified, but participated again in the game. What is the result? RULING Participating after being disqualified results in a technical foul. The technical foul is only penalized if it is discovered while being violated. Therefore, in (a), since A1 was no longer in the game, no technical foul shall be assessed. In (b), a technical foul shall be charged directly to team A’s head coach, A1 shall be removed from the game, team B shall receive two free throws and a division line throw in (10-6-3, 10.6.3). Day 50- Colors of Team Apparel PLAY Team A is wearing blue jerseys with gold trim. During pregame warmups, the officials notice A1 is wearing a black undershirt, blue wristbands and gold tights. Are those colors legal? RULING The color of the undershirt must be a single color similar to the torso of the game jersey, and thus a black undershirt is not legal. -

Fiba Glossary.Pdf

Glossary Basketball Glossary A Advance step: A step in which the defender's lead foot steps toward their man, and her back foot slides forward. Assist: A pass thrown to a player who immediately scores. B Backcourt: The half of the court a team is defending. The opposite of the frontcourt. Also used to describe parts of a team: backcourt = all guards (front court= all forwards and centers) Back cut: See cuts, Backdoor cut Backdoor cut: See cuts Back screen: See Screens Ball fake: A sudden movement by the player with the ball intended to cause the defender to move in one direction, allowing the passer to pass in another direction. Also called "pass fake." Ball reversal: Passing the ball from one side of the court to the other. Ball screen: See Screens Ball side: The half of the court (if the court is divided lengthwise) that the ball is on. Also called the "strong side." The opposite of the help side. Banana cut: See cuts Bank shot: A shot that hits the backboard before hitting the rim or going through the net. Baseball pass: A one-handed pass thrown like a baseball. Baseline: The line that marks the playing boundary at each end of the court. Also called the "end line." Baseline out-of-bounds play: The play used to return the ball to the court from outside the baseline along the opponent's basket. Basket cut: See cuts. Blindside screen: See Backscreen Glossary Block: (1) A violation in which a defender steps in front of a dribbler but is still moving when they collide. -

Illusionary Pattern Detection in Habitual Gamblers

Article Illusionary pattern detection in habitual gamblers WILKE, Andreas, et al. Abstract Does problem gambling arise from an illusion that patterns exist where there are none? Our prior research suggested that “hot hand,” a tendency to perceive illusory streaks in sequences, may be a human universal, tied to an evolutionary history of foraging for clumpy resources. Like other evolved propensities, this tendency might be expressed more stongly in some people than others, leading them to see luck where others see only chance. If the desire to gamble is enhanced by illusory pattern detection, such individual differences could be predictive of gambling risk. While previous research has suggested a potential link between cognitive strategies and propensity to gamble, no prior study has directly measured gamblers' cognitive strategies using behavioral choice tasks, and linked them to risk taking or gambling propensities. Using a computerized sequential decision-making paradigm that directly measured subjects' predictions of sequences, we found evidence that subjects who have a greater tendency to gamble also have a higher tendency to perceive illusionary patterns, as measured by their preferences for a random [...] Reference WILKE, Andreas, et al. Illusionary pattern detection in habitual gamblers. Evolution and Human Behavior, 2014, vol. 35, no. 4, p. 291-297 DOI : 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2014.02.010 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:76433 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 Evolution and Human Behavior 35 (2014) 291–297 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Evolution and Human Behavior journal homepage: www.ehbonline.org Original Article Illusionary pattern detection in habitual gamblers☆ Andreas Wilke a,⁎, Benjamin Scheibehenne b, Wolfgang Gaissmaier c, Paige McCanney a, H. -

Analyzing the Influence of Player Tracking Statistics on Winning Basketball Teams

Analyzing the Influence of Player Tracking Statistics on Winning Basketball Teams Igor Stan čin * and Alan Jovi ć* * University of Zagreb Faculty of Electrical Engineering and Computing / Department of Electronics, Microelectronics, Computer and Intelligent Systems, Unska 3, 10 000 Zagreb, Croatia [email protected], [email protected] Abstract - Basketball player tracking and hustle statistics year at the Olympic games, by winning a gold medal in the became available since 2013-2014 season from National majority of cases. Off the court, there are specialized Basketball Association (NBA), USA. These statistics provided personnel who try to improve each segment of the game, us with more detailed information about the played games. e.g. doctors, psychologists, basketball experts and scouts. In this paper, we analyze statistically significant differences One of the most interesting facts is that the teams in the in these recent statistical categories between winning and losing teams. The main goal is to identify the most significant league, and the league itself, have expert teams for data differences and thus obtain new insight about what it usually analysis that provide them with valuable information about may take to be a winner. The analysis is done on three every segment of the game. There are a few teams who different scales: marking a winner in each game as a winning make all of their decisions exclusively based on advanced team, marking teams with 50 or more wins at the end of the analysis of statistics. Few years ago, this part of season as a winning team, and marking teams with 50 or organization became even more important, because NBA more wins in a season, but considering only their winning invested into a computer vision system that collects games, as a winning team.