Shared Knowledge in High School Basketball Teams: Effects on Team Performance Jeff Weisman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019-20 MANUAL 2020 DIVISION II MEN’S and WOMEN’S BASKETBALL CHAMPIONSHIP HOST OPERATIONS MANUAL TABLE of CONTENTS No

2019-20 MANUAL 2020 DIVISION II MEN’S AND WOMEN’S BASKETBALL CHAMPIONSHIP HOST OPERATIONS MANUAL TABLE OF CONTENTS No. SECTION PAGE Introduction 1 Mission Statement 2 NCAA Men’s Basketball Committee and NCAA Staff Directory 3 NCAA Women’s Basketball Committee and NCAA Staff Directory 5 1 Awards and Mementos 7 2 Bands/Spirit Squads and Mascots 11 3 Banquet (Finals only) 12 4 Broadcasting/Internet 13 5 Commercialism/Contributors 13 6 Community Engagement (Finals only) 18 7 Critical Incident Response/Emergency Plan 19 8 Drug Testing 21 9 Competition Site, Equipment and Space Requirements 24 10 Financial Administration 30 11 Game Management 31 12 Insurance 34 13 Lodging 35 14 Meeting/Schedule of Events 37 15 Media/Credentials 37 16 Medical Procedures 46 17 Merchandise/Licensing 49 18 Officials 51 19 Participating Teams 52 20 Promotions and Marketing 53 21 Practices 57 22 Programs 58 23 Safety and Security Plan 61 24 Security 62 25 Tickets/Seating 63 26 Transportation 65 27 Volunteers 65 APPENDIXES A Credentials B Crowd Control/Corporate Champions/Partners Statement C Instructions for Public Address Announcer D Tournament Director’s Abbreviated Checklist E Neutrality Guidelines F Spit-Regional Schedule G Volunteer Waiver of Liability Form H Ticket Back Disclaimer I Social Media Guidelines J Microsite Guidelines K Regional Video Streaming Requirements L Guide to Live Video and Stats M Protective Security Advisor Information INTRODUCTION On behalf of the NCAA Division II Men’s and Women’s Basketball Committees, thank you for being an important part of the 2020 NCAA Division II Men’s and Women’s Basketball Championships. -

Ithaca at a Glance

The Football Program One of the school’s most successful athletic programs, the Ithaca football team also ranks among the top programs in the nation. The many highlights of Bomber football include the following: • Three NCAA Division III football championships, a total surpassed only by Augustana and Mount Union. • Seven appearances in the Division III national championship game, the Amos Alonzo Stagg Bowl. • Totals of 41 playoff games and 27 wins (both among the Division III leaders). • The fifth-best winning percentage in Division III (.667). • Eight Lambert/Meadowlands Cups, presented to the top small-college program in the East each season; and nine Eastern College Athletic Conference (ECAC) team of the year trophies. team reached the NCAA playoffs for the 15th time and the 2007 and 2008 teams reached the NCAA postseason as well. • ECAC championships in 1984, 1996, 1998, and 2004. When Butterfield arrived at Ithaca in 1967 for his first collegiate head coaching post, Ithaca’s schedule included top teams like Lehigh, West Chester, and C.W. Post. His first seven seasons Five years ago the Bombers recorded the program’s 400th victory. produced a 29-29 record before the program took off in the 1974 Ithaca’s Division III teams have been guided by coach Jim season. Butterfield, a 1997 inductee into the College Football Hall of Fame, Ithaca won 10 straight games that season, scoring over 25 points and current coach Mike Welch, a player and assistant coach under in all but one of those games. An NCAA playoff win over Slippery Butterfield. Rock put Ithaca into its first Amos Alonzo Stagg Bowl, where the Following Butterfield’s retirement in 1993, Welch was named team lost to Central (Iowa), 10-8. -

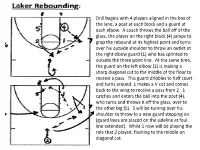

Drill Begins with 4 Players Aligned in the Box of the Lane, a Post at Each Block and a Guard at Each Elbow

Drill begins with 4 players aligned in the box of the lane, a post at each block and a guard at each elbow. A coach throws the ball off of the glass, the player on the right block (4) jumps to grap the rebound at its highest point and turns over his outside shoulder to throw an outlet ot the right elbow guard (1) who has sprinted to outside the three point line. At the same time, the guard on the left elbow (2) is making a sharp diagonal cut to the middle of the floor to receive a pass. This guard dribbles to half court and turns around. 1 makes a V cut and comes back to the wing to receive a pass from 2. 1 catches and enters the ball into the post (4), who turns and throws it off the glass, over to the other big (5). 5 will be turning over his shoulder to throw to a new guard stepping on (guard lines are placed on the sideline at foul line extended). While 1 now will be playing the role that 2 played, flashing to the middle on diagonal cut. Divide the team into three teams (A,B , and C) and have them line up as shown. The first player in line steps up and A has the ball. ‘A’ shoots a three. The ball is “live”, regardless of whether or not the shot is missed or made. (On a make the three doesn’t count). The game then becomes 1 on 1 on 1. With the player who grabbed the rebound being the one on offense. -

University of Colorado Football 2007 Letter-Of-Intent Signees

UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO FOOTBALL 2007 LETTER-OF-INTENT SIGNEES High School (24) Player Pos. Ht. Wt. Hometown (High School) ADKINS, Ethan............................... OL 6- 5 280 Castle Rock, Colo. (Douglas County) AHLES, Tyler.................................. ILB 6- 3 235 San Bernardino, Calif. (Cajon) BAHR, Matthew.............................. OL 6- 5 285 Dove Canyon, Calif. (Mission Viejo) BALLENGER, Matt.......................... QB 6- 4 215 Nampa, Idaho (Skyview) BEHRENS, Blake............................ OL 6- 4 285 Phoenix, Ariz. (Brophy Prep) CELESTINE, Kendrick.................... WR 6- 1 185 Mamou, La. (Mamou) DANIELS, Shawn............................ OL 6- 3 265 Evergreen, Colo. (Denver Mullen) GOREE, Eugene............................. DL 6- 2 285 Murfreesboro, Tenn. (Riverdale) HARTIGAN, Josh............................. OLB 6- 1 210 Fort Lauderdale, Fla. (Northeast) *HAWKINS, Jonathan .................... DB 5-10 185 Perris, Calif. (Rancho Verde) ILTIS, Mike .................................... OL 6- 3 285 Sarasota, Fla. (Riverview) JOHNSON, Devan........................... TE/HB 6- 1 230 Turtle Creek, Pa. (Woodland Hills) LOCKRIDGE, Brian........................ TB 5- 8 175 Trabuco Canyon, Calif. (Mission Viejo) MAIAVA, Kai ................................... C 6- 1 290 Wailuku, Hawai’i (Baldwin) MILLER, Ryan................................ OL 6- 8 310 Littleton, Colo. (Columbine) OBI, Conrad................................... DE 6- 4 245 Grayson, Ga. (Grayson) PERKINS, Anthony......................... DB 5-11 180 Northglenn, -

Intramural Sports Floor Hockey Rules

Princeton University Intramural Sports Floor Hockey Rules I. EQUIPMENT/UNIFORM/ELIGIBILITY a. All players must present their Princeton University ID in order to participate. b. The Intramural Department will provide sticks and balls. c. Players may wear gloves/mittens for hand protection. d. Each player must wear non-marking athletic shoes. e. Players may not wear hats with brims or jewelry during play. f. Goalies MUST wear a regulation catcher’s mask/goalie mask and chest protector, which are provided, if a goalie chooses to wear their own mask – it must be inspected by IM Supervisor before game begins. g. Goalies may wear a baseball glove on their non-stick hand and leg pads. h. All players must play in at least ONE regular season game in order to be eligible for playoffs. i. Players can only play for ONE Open/Women’s and/or ONE CoRec Team. j. Men’s and Women’s varsity Ice Hockey players and varsity Field Hockey players are not eligible. k. Only 2 Ice Hockey/Field Hockey Club players or 2 Junior Varsity players (or combination of the 2) are eligible to be on a team’s roster. II. NUMBER OF PLAYERS/GAME TIME/FORFEIT PENALTY a. Teams consist of 5 players on the floor at one time, four offensive players and a goalie. b. A minimum of 4 players is required to start and continue a game. c. For CoRec, the gender ratio is 3:2 with five players; and 2:2 with four players. d. A team that fails to have 4 players within 10 minutes after the start time of the game will forfeit/default the game. -

Praise for Everyone Hates a Ball Hog but They All Love a Scorer

Praise for Everyone Hates A Ball Hog But They All Love A Scorer “Coach Godwin's book offers a complete guide to being a team player, both on and off the court.” --Stack Magazine “Coach Godwin's book gives you insight on how to improve your game. If you are a young player trying to get better, this is a book I would recommend reading immediately.” --Clifford Warren, Head Coach Jacksonville University “Coach Godwin explains in understandable terms how to improve your game. A must have for any young player hoping to get to the next level.” --Khalid Salaam, Senior Editor, SLAM Magazine “I wish that I had this book when I was 16. I would have been a different and better player. Well done.” --Jeff Haefner, Co-owner, BreakthroughBasketball.com “The entire book is filled with gems, some new, some revised and some borrowed, but if you want to read one book this year on how to become a better scorer this is the book.” --Jerome Green, Hoopmasters.org “Detailed instruction on how to score, preaching that the game is more mental than physical. Good reading for the young set, who might put down that joystick for a few hours.” --CharlotteObserver.com Everyone Hates A Ball Hog But They All Love A Scorer ____________________________________________ The Complete Guide to Scoring Points On and Off the Basketball Court Coach Koran Godwin This book is dedicated to my mother, Rhonda who supported me every step of the way. Thanks for planting the seeds of success in my life. I am forever grateful. -

Tennessee 93 South Carolina 73 Feb. 17, 2021 | Thompson-Boling Arena | Knoxville, Tenn

Tennessee 93 South Carolina 73 Feb. 17, 2021 | Thompson-Boling Arena | Knoxville, Tenn. Tennessee Head Coach Rick Barnes On what he thought of VJ and Fulky’s performance tonight: “Again, the last couple of days of practice we were short of guys, and we just individually kept talking to guys that they have to get themselves involved, because we can only do so much from a coaching staff standpoint. Our offense since Fulky has been here hasn’t changed a whole lot, and if it had changed some, it’s because we have had to take advantage of some other talent. Otherwise, his position really hasn’t changed that much. We said they’re going to have to do it. I thought he did the best job of running tonight that he’s done all year. He really ran the floor hard and again I think he’s got to play quicker in the post, and he is wanting to catch it and spin and do this and that. He’s not going to get time to do that, unless he does his work early. With VJ, the last two days Santi wasn’t able to practice, so those three guys worked together, and I thought it probably helped VJ as much as any the last two days playing the point, and understanding what we want to do, and I thought he did a really good job with it.” On what the last few days were like with COVID circumstances: “Well, we knew regardless if the test results came back, we had to play by rule. -

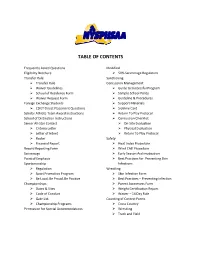

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Frequently Asked Questions Modified Eligibility Brochure Ø 50% Scrimmage Regulation Transfer Rule Sanctioning Ø Transfer Rule Concussion Management Ø Waiver Guidelines Ø Guide to Successful Program Ø School of Residence Form Ø Sample School Policy Ø Waiver Request Form Ø Guideline & Procedures Foreign Exchange Students Ø Support Materials Ø CSIET Direct Placement Questions Ø Sideline Card Scholar Athlete Team Award Instructions Ø Return To Play Protocol School of Distinction Instructions Ø Concussion Checklist Senior All-Star Contest Ø On-Site Evaluation Ø Criteria Letter Ø Physical Evaluation Ø Letter of Intent Ø Return To Play Protocol Ø Roster Safety Ø Financial Report Ø Heat Index Procedure Record Reporting Form Ø Wind Chill Procedure Scrimmage Ø Early Season Acclimatization Point of Emphasis Ø Best Practices for Preventing Skin Sportsmanship Infections Ø Regulation Wrestling Ø Sport Promotion Program Ø Skin Infection Form Ø Be Loud, Be Proud, Be Positive Ø Best Practices – Preventing Infection Championships Ø Parent Awareness Form Ø Dates & Sites Ø Weight Certification Report Ø Code of Conduct Ø Waiver – 14 Day Rule Ø Gate List Counting of Contest Forms Ø Championship Programs Ø Cross Country Permission for Special Accommodations Ø Wrestling Ø Track and Field TABLE OF CONTENTS “FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS” General ................................................................................................................................................1 Amateur Regulations ..........................................................................................................................4 -

Georgia Tech Basketball 2018-19

2018-19 GEORGIA TECH BASKETBALL GAME NOTES @GTMBB • @GTJOSHPASTNER GEORGIA TECH BASKETBALL 2018-19 ACC Champions 1985, 1990, 1993 • Final Four 1990, 2004 • 16 NCAA Tournament appearances GEORGIA TECH SEASON REVIEW 2018-19 Schedule/Results Final Record: 14-18 overall, 6-12 ACC (10th place) N3 FLORIDA TECH (exhibition) W, 87-36 In a Nutshell GEORGIA TECH AT-A-GLANCE N9 LAMAR W, 88-69 Georgia Tech (14-18, 6-12 ACC) completed its third N13 at Tennessee (5/6) L, 53-66 season under head coach Josh Pastner by earning the No. 10 2018-19 rankings (AP/coaches/NET) nr | nr | 126 N16 EAST CAROLINA W, 79-54 seed for ACC Tournament, its highest since 2016, by defeating 2018-19 record 14-18 (11-7 home, 3-9 away, 0-2 neutral) N21 UT RIO GRANDE VALLEY W, 72-44 Boston College (81-78 in overtime at home) and NC State (63- ACC record 6-12 (10th place) N23 PRAIRIE VIEW A&M W, 65-54 61 on the road) in its final two regular season games. The Yellow ACC Tournament (10 seed) lost to Notre Dame (78-71), 1st round N28 at Northwestern+ L, 61-67 Jackets were eliminated in the opening round by Notre Dame, Head coach Josh Pastner (Arizona, 1997) D1 vs. St. John’s [Miami, Fla.]# (rv) L, 73-76 78-71. D9 FLORIDA A&M W, 73-40 Career record/at GT 215-126 (10th yr) | 48-53 (3rd yr) D17 GARDNER-WEBB L, 69-79 Starting Lineup Starters Returning/Lost *5/0 D19 at Arkansas W, 69-65 • Rise above - The Yellow Jackets finished the season Letterwinners Returning/Lost 10/5 D22 GEORGIA L, 59-70 10th in the ACC after being projected to finish no higher than *based on end-of-season starting five D28 KENNESAW STATE W, 87-57 13th in the preseason. -

SMA Honor System Undergoes Series of Changes, Corps Elects Nominees Editors and Managers of the Kablegram Honor Committee Members Were Elected Yesterday

&he Kabletjram Vol. 39 Staunton Military Academy, Kable Station, Staunton, Virginia, Friday, November 4, 1955 No. 3 SMA Honor System Undergoes Series Of Changes, Corps Elects Nominees Editors and Managers of The Kablegram Honor Committee Members Were Elected Yesterday East Wednesday afternoon the Corps nominated members from each class for the 1955-1956 Honor Committee. Yester- day, the final voting took place. Members of the Senior Class who were elected are Hector Cases and William Foard while Arthur Stern and Bob Fraser were elected in the Junior Class. Bob Bird and John Morris were elected in the Sophomore and Freshman Classes respectively. Cadet Major Lee Lawrence is an automatic member and president of the committee. This constitutes the first time in the history of the school that Honor Committee members have been elected, not appointed. At the beginning of the year, Colonel Dey, Superintend- ant, appointed a committee of three faculty officers to study the honor systems of outstanding institutions of higher learn- ing. Col. Enslow, Captain Mahone, SMA Varsity and Jayvees and Captain Haddock, the three fac- Play During The Week-End ulty, studied the systems, and upon The Staunton Military Academy arriving at a satisfactory honor sys- Junior Varsity football team will tem, turned it in to the Superintend- travel to Charlottesville, Va. tonight to play Albermarle High School ant. One of the articles of the new Front Row: Wm. Foard, Hector Cases, Jack Swagler. Top Row: John Kork, Jim Pittman, under the lights. The varsity will system says that the head of the Jon Levy, Jim Wilson. -

Horace Mann School ATHLETIC HANDBOOK

Horace Mann School ATHLETIC HANDBOOK For STUDENT-ATHLETES AND PARENTS This handbook has been developed with the intent of helping to make interscholastic athletics at Horace Mann as simple, effective, and as enjoyable as possible. It is hoped that by assembling all the material that relates to the administration of athletic programs in one central volume, parents and student athletes will have a better understanding of these practices, policies, and procedures with a more convenient reference to them. This handbook is intended to clearly state and define methods for accomplishing specific tasks, to outline basic goals, and to recommend guidelines for the maintenance of high standards in the overall athletic program. It is also intended to be a practical tool that answers more questions than it creates and which parents and student athletes find to be a usable resource and not just another item to be filed away. This handbook is designed to supplement and not replace direct communication among all members of the athletic community. The Athletic Director will always be available to provide whatever assistance is required in pursuit of common goals. Finally, any suggestions you might have for improving this handbook or any of its content is welcome. Horace Mann Athletics Page 1 HORACE MANN ATHLETIC OFFERINGS FALL VARSITY JV MOD-A MOD-B Boys’ Cross Country X X Girls’ Cross Country X X Field Hockey X X X Boys’ Football X X X Boys’ Soccer X X X X Girls’ Soccer X X X Girls’ Tennis X X X Girls’ Volleyball X X X X Mixed Water Polo X X X WINTER -

Parents, Hall Boys Tennis Team

To: Parents, Hall Boys Tennis Team (Varsity and Junior Varsity-Team 1 and Team 2 From: Jim Solomon, Head Coach ([email protected]), ([email protected]); Sean Passan, Assistant Coach ([email protected]), Steven Smith, Assistant Coach ([email protected]) Will Carpenter, Adam Glassman and Henry Glucksman, captains. Welcome to the 2018 spring sports season and the Hall Boys Tennis family. The varsity (Team 1) has an 18 match schedule that includes league, non-league and tournament play and two pre-season scrimmages. The Junior Varsity (Team 2) has 12 scheduled matches--some co-ed. Both schedules may be found on Hall’s Athletic Dept website. Few public schools have multiple teams, but with our outstanding facility, support of the Athletic Department and heightened interest among student-athletes, Hall is a nationally recognized USTA “No Cut Tennis” program and is the largest boys team in Connecticut. We are fortunate to have two returning assistant coaches, Sean Passan and Steven Smith. Philosophy: Hall Tennis has an excellent reputation for its high standards of performance and conduct on the courts. As coaches we try to achieve success by balancing team and individual goals and by focusing on performance rather than outcome objectives. Players strive to improve competitive skills, strategy, mental toughness and physical conditioning. As with any individual sport, it is crucial that we build a strong sense of team. With the captains’ capable assistance, we emphasize team commitment as well as the privilege of representing Hall Tennis, Hall High School, their families and themselves. We hope to instill a love of tennis as a life sport.