PDF Van Tekst

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Latin Books Published in Paris, 1501-1540

Latin Books Published in Paris, 1501-1540 Sophie Mullins This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 6 September 2013 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, Sophie Anne Mullins hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 76,400 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September 2007 and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in September 2007; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between [2007] and 2013. (If you received assistance in writing from anyone other than your supervisor/s): I, …..., received assistance in the writing of this thesis in respect of [language, grammar, spelling or syntax], which was provided by …… Date 2/5/14 signature of candidate ……… 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. Date 2/5/14 signature of supervisor ……… 3. Permission for electronic publication: (to be signed by both candidate and supervisor) In submitting this thesis to the University of St Andrews I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations of the University Library for the time being in force, subject to any copyright vested in the work not being affected thereby. -

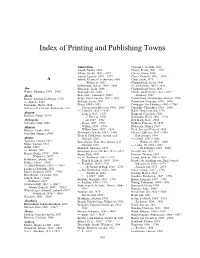

Index of Printing and Publishing Towns

Index of Printing and Publishing Towns Amsterdam Carpentier, Jacobus, 1633 Aboab, Eliahu, 1644 Chayer, Pierre, 1691 ± 1700 Athias, Joseph, 1661 ± 1667 Claesse, Frans, 1654 Autein, Laurens, 1670 ± 1671 Claesz, Cornelis, 1602 ± 1610 A Baardt, Rieuwert Dircksz van, 1644 Claus, Jacob, 1676 —, —, Widow of, 1652 Cloppenburgh, Evert, 1640 Bakkamude, Daniel, 1666 ± 1668 —, Jan Evertsz, 1603 ± 1630 A˚ bo Benjamin, Jacob, 1668 Cloppenburgh Press, 1640 Winter, Johannes, 1689 ± 1692 Benningh, Jan, 1655 Colom, Jacob Aertsz, 1633 ± 1671 Alcalá Benveniste, Immanuel, 1658? —, Johannes, 1648 Brocar, Arnaldo Guillén de, 1516 Berge, Pieter van den, 1661 ± 1665 Commelinus, Hieronymus, Heirs of, 1626 —, Juan de, 1541 Bisterus, Lucas, 1680 Commelyn, Casparus, 1660 ± 1669 Fernández, María, 1646 Blaeu, 1684 ± 1685 Compagnie des Libraires, 1685 ± 1700? Ximenez de Cisneros, Franciscus, 1517 —, Typographia Blaviana, 1663 ± 1693 Cunradus, Christoffel, 1651 ± 1660 —, Cornelis, 1635 ± 1648? Dalen, Daniel van den, 1700 Alençon —, Joan, I, 1635 ± 1675 Dankertz, Cornelius, 1659 Du Bois, Simon, 1530? —, —, I, Heirs of, 1679 Desbordes, Henri, 1683 ± 1700 Alethopolis —, —, II, 1687 ± 1701 Dittelbach, Pierre, 1689 Valerius, Cajus, 1665 —, Pieter, 1687 ± 1701 Du Bois, François, II, 1676 Alkmaar —, Willem, 1633 ± 1688 Du Fresne, Daniel, 1687 Meester, Jacob, 1605 —, Willem Jansz, 1617 ± 1639 Dyck, Jan van, Heirs of, 1685 Oorschot, Joannes, 1605 Blankaart, Cornelis, 1687 ± 1688 Elsevier, Officina, 1637 ± 1680 Blum & Conbalense, (pseud. of S. —, Bonaventure, 1608 Altdorf Mathijs), -

Bibliography

BIbLIOGRApHY NB: Early modern translations are listed under the translator’s name, except in cases of anonymous translations, which are listed under the name of the author. Modern translations are also listed under the name of the author. PRIMARY Ainsworth, Henry. 1609. A defence of the Holy Scriptures, worship, and ministerie, used in the Christian Churches separated from Antichrist.... Amsterdam: Giles Thorp. Anon. 1527?. A copy of the letters wherin the ... king Henry the eight, ... made answere vnto a certayne letter of M. Luther... [anon. tr.]. London: R. Pynson. ———. 1549?. The prayse and commendacion of suche as sought comenwelthes: and to the co[n]trary, the ende and discommendacion of such as sought priuate welthes. Gathered both out of the Scripture and Phylozophers. London: Anthony Scoloker. ———. c.1550. A Ruful complaynt of the publyke weale to Englande. London: Thomas Raynald. ———. 1588. A discourse vpon the present state of France [anon. tr.]. London: John Wolfe. ———. 1632. All the French Psalm tunes with English words ... used in the Reformed churches of France and Germany ... [anon. tr.]. London: Thomas Harper. ———. 1642. Articles of Impeachment exhibited in Parliament, against Spencer Earle of Northamp[ton], William Earle of Devonsh[ire], Henry Earle of Dover, Henry Earle of Monmouth, Robert Lord Rich, Charles Lord Howard Charlton, Charles L. Grey of Ruthen, Thomas Lord Coventry, Arthur Lord Chapell, &c. For severall high Crimes and Misdemeanours.... London: T. F for J. Y. © The Author(s) 2018 279 M.-A. Belle, B. M. Hosington (eds.), Thresholds of Translation, Early Modern Literature in History, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-72772-1 280 BIBLIOGRAPHY Ashley, Robert, tr. -

Download Catalogue

CONTINENTAL & EARLY PRINTED BOOKS FROM THE LIBRARY OF THE LATE DR. ARTHUR TELLER (RIVERDALE, NY) 1 ABU’L-FEDA, ISMAEL. De Vita et Rebus Gestis Mohammedis. FIRST EDITION. Printer’s device on title. Latin and Arabic in parallel columns. Edited and translated by Joannes Gagnier. Browned. Recent vellum-backed boards, rubbed. Folio. Oxford, Sheldonian Theatre, 1723. $500 - $700 ❧ An important work for the study of 18th-century Orientalism. The author of this life of the Prophet Mohammed, Ismael Abu’l-Feda (1273-1331), from whose “Annals” this study is derived, was a Kurdish historian, geographer and local governor of Hama, Syria. 2 AMMIANUS MARCELLINIUS. Rerum Gestarum qui de xxxi Supersunt, Libri XVIII (Res Gestae). Edited by Jacobus Grovonius (Jacob Gronow). Additional engraved title. Text illustrations and engraved plates (including folding by ROMEYN DE HOOGHE). Browned, light wear. Contemporary vellum, worn. Lg. 4to. Leiden, P. Vander, 1693. $300 - $500 ❧ Although originally 31 books, the first 13 volumes of this history have been lost. The surviving 18 books describe Roman military campaigns and political life from the years 353-378. “An admirable edition, highly spoken of by Ernesti and Harwood, and well known in the republic of literature. To the notes of Lindenbrogius and other editors (placed below the text) Gronovius has added some excellent annotations of his own” (Dibdin I:257). 3 APOLLONIUS OF RHODES. Argonauticorum, Carmine Heroico. Translated into Latin by Valentinus Rotmarus. Two parts in one. Later vellum. 12mo. Basle, Henricus Petrus, 1572. $150 - $200 4 ATTAR, FARID AL-DIN. Tezkereh-i-Evliâ. Le Memorial des Saints. Traduit sur le Manuscrit Ouigour de la Bibliothèque Nationale. -

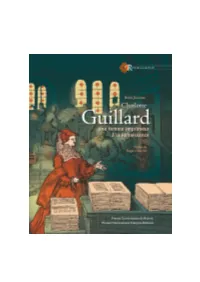

Charlotte Guillard Est Une Figure Exceptionnelle De La Renaissance Française

4 Financement de l’ouvrage Cet ouvrage est diffusé en accès ouvert dans le cadre du projet OpenEdition Books Select. Ce programme de financement participatif, coordonné par OpenEdition en partenariat avec Knowledge Unlatched et le consortium Couperin, permet aux bibliothèques de contribuer à la libération de contenus provenant d'éditeurs majeurs dans le domaine des sciences humaines et sociales. La liste des bibliothèques ayant contribué financièrement à la libération de cet ouvrage se trouve ici : https://www.openedition.org/22515. This book is published open access as part of the OpenEdition Books Select project. This crowdfunding program is coordinated by OpenEdition in partnership with Knowledge Unlatched and the French library consortium Couperin. Thanks to the initiative, libraries can contribute to unlatch content from key publishers in the Humanities and Social Sciences. Discover all the libraries that helped to make this book available open access: https:// www.openedition.org/22515?lang=en. 1 Charlotte Guillard est une figure exceptionnelle de la Renaissance française. Originaire du Maine, elle mène à Paris une carrière brillante dans la typographie. Veuve tour à tour des imprimeurs Berthold Rembolt et Claude Chevallon, elle administre en maîtresse femme l’atelier du Soleil d’Or pendant près de vingt ans, de 1537 à 1557. Sous sa direction, l’entreprise accapare le marché de l’édition juridique et des Pères de l’Église, publiant des éditions savantes préparées par quelques- uns des plus illustres humanistes parisiens (Antoine Macault, Jacques Toussain, Jean Du Tillet, Guillaume Postel…). Associant dans un même projet intellectuel les théologiens les plus conservateurs et les lettrés les plus épris de nouveauté, sa production témoigne de la vivacité des débats qui agitent les milieux intellectuels au siècle des Réformes. -

Early Printed Books in the Heiko A. Oberman Library at the University of Arizona

EARLY PRINTED BOOKS IN THE HEIKO A. OBERMAN LIBRARY AT THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA Carl T. Berkhout EARLY PRINTED BOOKS IN THE HEIKO A. OBERMAN LIBRARY AT THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA With an Appendix: Selected Recent Acquisitions CARL T. BERKHOUT Department of Special Collections University of Arizona Libraries Tucson 2017 The cover illustration is the device on the title pages of nos. 19 and 20. Copyright © 2017 Arizona Board of Regents for the University of Arizona Libraries Contents Preface 5 Bibliography 9 Early Printed Books 14 Appendix: Selected Recent Acquisitions 51 Indexes Authors, Editors, and Translators 71 Printers and Publishers 73 Provenance 75 4 EAR LY PRINTED BOOKS IN THE HEIKO A. OBERMAN LIBRARY 5 Preface Ut conclave sine libris, ita corpus sine anima. EVEN WHILE DECLINING that maxim’s common but dubious attribution to Cicero, whose writings he knew well, Heiko A. Oberman genially agreed that a room without books is like a body without a soul. Every room in Oberman’s pleasant home in the Santa Catalina foothills overlooking Tucson did in fact have its books—many books—and indeed a soul. From his student years in his native Utrecht and at Oxford and then through his long career of research and teaching at Harvard University, the Universität Tübingen, and the University of Arizona, he had assembled an extensive personal library in support of his untiring scholarship in late medieval and Reformation history. Shortly before his death on 22 April 2001 he and his family offered his books for acquisition by the University of Arizona Libraries as part of an arrangement that would establish a chair in his name in the College of Social and Behavioral Sciences’ Division for Late Medieval and Reformation Studies, a unit that he had founded five years after his arrival at the University in 1984. -

ERASMUS' RELATIONS with HIS PRINTERS. 299 Hertogenbosch in Brabant, Kept by the Brethren of the Common Life; and There Two More Years Were Spent

ERASMUS' RELATIONS WITH HIS Downloaded from PRINTERS. By P. S. ALLEN. http://library.oxfordjournals.org/ Read £5th iI/arch, £9£5. OS1' of us probably can recall something of the sensations with which we first saw ourselves in print. A boy reading his name for the first time in his school magazine feels to have stepped upon the stage of the at University of California, Santa Barbara on July 9, 2015 world and become almost a public personage: as though all eyes that passed over the important page could not but be rivetted upon initials and letters which to him seem so familiar. And when first he sees in print something of his own composition, what a wonderful adventure! the halting sentences are transfigured with dignity by their appearance in type, until, as he reads, he feels almost as though an oracle had spoken. If such thoughts can arise now, what must it have been when the art of printing was young! In the days of hireling scribes, ploughing out their work with no guarantee of uniformity, a budding author might allow himself ten or twenty copies of some composition, for presentation to patrons and friends; hoping that admiration might win for it wider existence. But if once he could persuade a printer to accept his work, his name might travel, whilst he slept, into all lands, from the borders of the "uncombed Russians" to the new dominions that a united Spain was 298 ERASlIIUS' RELA TlONS WITH HIS PRINTERS. founding across the Western seas. To a reputation for elegance he might add the credit of being modem and progressive, not a mere runner after novelties, but ready to profit by man's great inventions which had "come to stay." Hence it is that by 1$00 we find many names, often otherwise quite unknown, beside that of the author in the opening and closing Downloaded from pages of books. -

Download PDF Version

Catalogue 117 ‘t Goy 2019 antiquariaat FORUM & ASHER Rare Books Catalogue 117 ‘t Goy 2019 Catalogue 117 Extensive descriptions and images available on request. All offers are without engagement and subject to prior sale. All items in this list are complete and in good condition unless stated otherwise. Any item not agreeing with the description may be returned within one week after receipt. Prices are in eur (€). Postage and insurance are not included. VAT is charged at the standard rate to all EU customers. EU customers: please quote your VAT number when placing orders. Preferred mode of payment: in advance, wire transfer or bankcheck. Arrange- ments can be made for MasterCard and VisaCard. Ownership of goods does not pass to the purchaser until the price has been paid in full. General conditions of sale are those laid down in the ILAB Code of Usages and Customs, which can be viewed at: <http://www.ilab.org/eng/ilab/code.html> New customers are requested to provide references when ordering. Tuurdijk 16 Tuurdijk 16 3997 ms ‘t Goy 3997 ms ‘t Goy The Netherlands The Netherlands Phone: +31 (0)30 6011955 Phone: +31 (0)30 6011955 Fax: +31 (0)30 6011813 Fax: +31 (0)30 6011813 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.forumrarebooks.com Web: www.asherbooks.com Front cover no. 81 on p. 46. Inside front cover no. 21 on p. 13. Title page no. 89 on p. 50. Back cover no. 169 on p. 90. v 1.01 · 15 Jan 2020 Translations of Aesop’s fables into Hindi, Braj Bhasha, Bengali, Sanskrit, Persian and Arabic 1. -

In Diesem Buch Finden Sie Abbildungen Von Druckern Und Druckermarken, Auf Denen Sich Der Drucker Abbildet

In diesem Buch finden Sie Abbildungen von Druckern und Druckermarken, auf denen sich der Drucker abbildet. B41, 12.2015 Versammelt sind hier die nachstenden Drucker Peter Benewitz Jacopo Pocatela da Borgofranco Girolamo Cartolari William Powell William Caxton Richard Pynson Claude Chevallon Ludovicus de Ravescot Christoph Cofman Georg Rhau John Day Gilles (Aegidius) Rooman Hans Dorn Jean Le Rouge, Christian Egenolff Nicolas Le Rouge, Robert Estienne d.Ä. Pierre Le Rouge und und andere Drucker der Guillaume Le Rouge Familie Peter Schoiffer d.Ä. Sigmund Feyerabend Georgij Franzisk Skorina Richard Grafton Zacharias Solin Arnåo Guillen de Brocar Johannes Sultzbach Henne Gensfleisch Leonhardt Thurneysser Etienne Guyard Primoz Trubar Johannes Haselberg Antoine Verard Johann und Konrad Hist Andries Verschout Laurent Hyllaire Willem Verwilt Jakkob Koebel Heinrich Vogtherr Albert Kunne Willem Vorstermann Giovanni da Legnano und Brüder John Wight Aldo Manuzio Thomas Wolff Francesco Marcolini Reginald Wolfe Nicolaus Marschalk Wynkyn de Worde Einleitung Versammelt sind in diesem Büchlein »Bildnisse« von Druckern und Verlegern. Die überwiegende Anzahl stammt von den Bücherzeichen dieser Drucker. Ein kleiner Ausflug in die Kunstgeschichte: Zwischen 1500 und 1510 entsteht der monumentale Holzschnitt »Große Ansicht von Florenz«. Hier setzt sich zum er- sten Mal in der Kunstgeschichte der Schöpfer der Zeichnung selbst ins Bild. Das zeugt vom gewachsenen Selbstbewußtsein des Künstlers. So können auch die Bücherzeichen verstanden werden, in denen sich der Druckerherr selbst abbil- det. Verwies die erste verwendete Marke (Schoiffer und Fust) noch auf die Art der Produktionstechnik, nämlich auf den Druck mit beweglichen Lettern (anstelle der handgeschriebenen Bücher, der Manuskripte), entwickeln sich rasch andere Druckermarken. Drucker oder Verleger, die sich in ihrem Firmenzeichen selbst abbildeten, besaßen also – so könnte man annehmen – ein besonders großes Selbstvertrauen. -

The Flyleaf, 1989

TiiiiiiiiiiiiiiAiiiinJiiiuiiiiiiiiuminji 3 1272 00694 0074 RICE UNIVERSITY FONDREN LIBRARY Founded under the charter of the university dated May 18, 1891, the library was estab- lished in 1913. Its present facility was dedicated November 4, 1949, and rededicated in 1969 after a substantial addition, both made possible by gifts of Ella F. Fondren, her children, and the Fondren Foundation and Trust as a tribute to Walter William Fondren. The library recorded its half -millionth volume in 1965; its one millionth volume was celebrated April 22, 1979. THE FRIENDS OF FONDREN LIBRARY The Friends of Fondren Library was founded in 1950 as an association of library supporters interested m increasing and making better known the resources of Fondren Library at Rice University. The Friends, through members' contributions and sponsorship of a memorial and honor gift program, secure gifts and bequests and provide funds for the purchase of rare books, manuscripts, and other materials that could not otherwise be acquired by the library. THE FLYLEAF Founded October 1950 and published quarterly by the Friends of Fondren Library, Rice University, RO. Box 1892, Houston, Texas 77251, as a record of Fondren Library's and Friends' activities, and of the generosity of the library's supporters. BOARD OF DIRECTORS 1989-90 OFFICERS Mr. Edgar O. Lovett II, President Mrs. Frank B. Davis, Vice-President, Membership Mr. David S. Elder, Vice-President, Programs Mr. J. Richard Luna, Treasurer Mrs. Gus Schill, Jr., Secretary » Mr. David D. Itz, lmrr\ediate Past President Dr. Samuel M. Carrington, Jr., University Librarian (ex-officio) Dr. Edward F. Hayes, Vice-President /or Graduate Studies, Research, and Informatiori Systems Dr.