Second Nature: an Environmental History of New England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NHHS Consuming Views

CONTRIBUTORS Heidi Applegate wrote an introductory essay for Hudson River Janice T. Driesbach is the director of the Sheldon Memorial Art School Visions: The Landscapes of Sanford R. Gifford (Metro- Gallery and Sculpture Garden at the University of Nebraska- politan Museum of Art, 2003). Formerly of the National Lincoln. She is the author of Direct from Nature: The Oil Gallery of Art, she is now a doctoral candidate in art history at Sketches of Thomas Hill (Yosemite Association in association Columbia University. with the Crocker Art Museum, 1997). Wesley G. Balla is director of collections and exhibitions at the Donna-Belle Garvin is the editor of Historical New Hampshire New Hampshire Historical Society. He was previously curator and former curator of the New Hampshire Historical Society. of history at the Albany Institute of History and Art. He has She is coauthor of the Society’s On the Road North of Boston published on both New York and New Hampshire topics in so- (1988), as well as of the catalog entries for its 1982 Shapleigh cial and cultural history. and 1996 Champney exhibitions. Georgia Brady Barnhill, the Andrew W. Mellon Curator of Elton W. Hall produced an exhibition and catalog on New Bed- Graphic Arts at the American Antiquarian Society, is an au- ford, Massachusetts, artist R. Swain Gifford while curator of thority on printed views of the White Mountains. Her “Depic- the Old Dartmouth Historical Society. Now executive director tions of the White Mountains in the Popular Press” appeared in of the Early American Industries Association, he has published Historical New Hampshire in 1999. -

As Time Passes Over the Land

s Time Passes over theLand A White Mountain Art As Time Passes over the Land is published on the occasion of the exhibition As Time Passes over the Land presented at the Karl Drerup Art Gallery, Plymouth State University, Plymouth, NH February 8–April 11, 2011 This exhibition showcases the multifaceted nature of exhibitions and collections featured in the new Museum of the White Mountains, opening at Plymouth State University in 2012 The Museum of the White Mountains will preserve and promote the unique history, culture, and environmental legacy of the region, as well as provide unique collections-based, archival, and digital learning resources serving researchers, students, and the public. Project Director: Catherine S. Amidon Curator: Marcia Schmidt Blaine Text by Marcia Schmidt Blaine and Mark Green Edited by Jennifer Philion and Rebecca Chappell Designed by Sandra Coe Photography by John Hession Printed and bound by Penmor Lithographers Front cover The Crawford Valley from Mount Willard, 1877 Frank Henry Shapleigh Oil on canvas, 21 x 36 inches From the collection of P. Andrews and Linda H. McLane © 2011 Mount Washington from Intervale, North Conway, First Snow, 1851 Willhelm Heine Oil on canvas, 6 x 12 inches Private collection Haying in the Pemigewasset Valley, undated Samuel W. Griggs Oil on canvas, 18 x 30 inches Private collection Plymouth State University is proud to present As Time Passes over the about rural villages and urban perceptions, about stories and historical Land, an exhibit that celebrates New Hampshire’s splendid heritage of events that shaped the region, about environmental change—As Time White Mountain School of painting. -

Tatewell Gallery

WWW.GRANITEQUILL.COM | OCTOBER 2012 | SENIOR LIFESTYLES | PAGE 17 Tips for seniors on managing health care costs Finding the Medicare coverage that year by switching drug plans. "I thought best fits their needs and their pocket- a mail-order prescription plan was best books is challenging for many seniors. for me, but their specialists proved me Health care plans make changes to their wrong about this, and I am so happy," coverage. People's health conditions she says. change. Not keeping on top of these 3. Be proactive. Having known changes can mean problems. Suddenly and been around seniors, Hercules says seniors may find they don't have needed she is saddened that so many settle for coverage, their doctor no longer takes high costs or keep the same Medicare their plan, or they face steep medical or plan year after year because of a lack of prescription drug costs. niors can capitalize on those savings by understanding. That's why it's essential to review knowing exactly what they are paying Just as seniors review their finances Medicare coverage and individual needs for and shop around for better prescrip- or taxes each year, Medicare annual each year, and to use the Medicare an- tion prices and ask about costs. For addi- enrollment is the ideal time to review nual open enrollment period to make tional savings, use generic medications. health care coverage, Walters says. "It's changes to coverage. 2. Ask for help. In addition to guid- OK to admit it's confusing and that help 1. Be an informed consumer. -

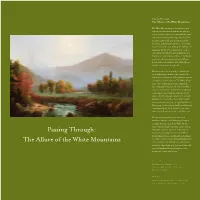

Passing Through: the Allure of the White Mountains

Passing Through: The Allure of the White Mountains The White Mountains presented nineteenth- century travelers with an American landscape: tamed and welcoming areas surrounded by raw and often terrifying wilderness. Drawn by the natural beauty of the area as well as geologic, botanical, and cultural curiosities, the wealthy began touring the area, seeking the sublime and inspiring. By the 1830s, many small-town tav- erns and rural farmers began lodging the new travelers as a way to make ends meet. Gradually, profit-minded entrepreneurs opened larger hotels with better facilities. The White Moun- tains became a mecca for the elite. The less well-to-do were able to join the elite after midcentury, thanks to the arrival of the railroad and an increase in the number of more affordable accommodations. The White Moun- tains, close to large East Coast populations, were alluringly beautiful. After the Civil War, a cascade of tourists from the lower-middle class to the upper class began choosing the moun- tains as their destination. A new style of travel developed as the middle-class tourists sought amusement and recreation in a packaged form. This group of travelers was used to working and commuting by the clock. Travel became more time-oriented, space-specific, and democratic. The speed of train travel, the increased numbers of guests, and a widening variety of accommodations opened the White Moun- tains to larger groups of people. As the nation turned its collective eyes west or focused on Passing Through: the benefits of industrialization, the White Mountains provided a nearby and increasingly accessible escape from the multiplying pressures The Allure of the White Mountains of modern life, but with urban comforts and amenities. -

Download in New Hampshire – August 2017

AUGUST 2017 IN NewYour Guide to What’s Happening Hampshire in the Granite State Presorted Standard Presorted U.S. POSTAGE U.S. Postal Customer Postal Portsmouth, NH PAID Permit #130 Permit ECRWSS See us online at Dan Houde/ www.granitequill.com Wiseguy Creative FREE Photography PAGE 2 | SUMMER IN NEW HAMPSHIRE | AUGusT 2017 Drive • Tour • Explore MOUNT WASHINGTON Just 20 Minutes North of North Conway DRIVE YOURSELF SHORT SCENIC HIKES Book Online Get $5 Off Per Person On 9:00 AM Guided Tours (24 hours in advance) GUIDED ADVENTURES Rt. 16, Pinkham Notch, Gorham, NH MtWashingtonAutoRoad.com AUGusT 2017 | SUMMER IN NEW HAMPSHIRE | PAGE 3 Seacoast Science Center joins US Light House Passport Program Rye, NH - The Seacoast Science Center in Odiorne Point State Park is now a participant in the United States Light House Society’s Light House Passport Program, and is the only location in New Hampshire and southern Maine where passport holders can collect stamps year-round. From the Park and the Center, you can view four lighthouses, including Portsmouth Harbor, White Island, Whaleback, and Boon Island, as well as the Wood Island Life Saving Station and a U.S. Life Saving Service Key Post. The Key Post, once located on Appledore Island, is on display in the Center, on loan from the Star Island Corporation. You can join the United States Light House Society (USLHS) and purchase your Light House Passport Program Passport Book online at uslhs.org or you can purchase your Passport in the Center’s Nature Store when you visit. By participating in the USLHS Passport Program, you’ll have taken the first step in helping to preserve lighthouses, while having fun viewing or visiting historic light houses around the country. -

Jasper Cropsey, Painter (PDF)

• Motto/Logo: (()Dana Yodice) • Slide Sh ow of Work s: (Megan VanDervoort) • Thesis: (Group) • Place: (Jenn Ric ker d) • Biography: (Dana Yodice) • Lesson Plan: (Jenn Rickerd, Tessa • His tor ical C ont ext : (Tessa Carp ico) Carp ico, Dana Yo dice ) • Overall Influences: (Jenn Rickerd) • Conclusion: (Megan VanDervoort) • Hudson River Valley Influences: • Itinerary: (Group) (Jen Rickerd) • Website: (Dana Yodice/Jen Fowler) Echo Lake Known as “America’s painter of autumn,” Cropsey was most inspired by the Hudson River Valley and its scenic fall foliage. His paintings portra yed the vibrant changing colors of the trees and the reflection of the mountain ranges in the Hudson River. Because of this inspiration, Cropsey was best known as “America’s painter of autumn”. • Founded the American Society of Painters in Water • Born in 1823 Colors • Received early training as • EhibidExhibited at : an architect & set up his • National Academy of own office: 1843. Design • Boston Athenaeum • National Academy of • Royal Academy in Design: 1844 London • Hudson River School • Died in 1900 • Traveled in Europe from 1847 to 1849 •Post civil war •Preoccupation with: •nature •beautiful things •Panoramic image ry Queen Victoria •Ignored industrial setting •Aesthetic symbols •Romantic realist • Architecture • RfNtReverence for Nature • Landscape paintings by • Thomas Cole "Notch in the White Mountains" by Thomas Cole •Claude Lorrain •Trips to Europe •Philosophers and Aestheticians: •Ralph Waldo Emerson •Sir Jos h ua R eyn ol ds "Seaport at Sunset" 1639 - by -

The Nineteenth-Century Roots of the Outdoor Education Movement

Boston University OpenBU http://open.bu.edu Theses & Dissertations Boston University Theses & Dissertations 2015 Crafting an outdoor classroom: the nineteenth-century roots of the outdoor education movement https://hdl.handle.net/2144/16023 Boston University BOSTON UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES Dissertation CRAFTING AN OUTDOOR CLASSROOM: THE NINETEENTH-CENTURY ROOTS OF THE OUTDOOR EDUCATION MOVEMENT by PAUL JOHN HUTCHINSON B.A., Gettysburg College, 1998 M.S., Minnesota State University-Mankato, 2001 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 © Copyright by PAUL JOHN HUTCHINSON 2015 Approved by First Reader Nina Silber, Ph.D. Professor of History Second Reader William D. Moore, Ph.D. Associate Professor of American Material Culture DEDICATION This dissertation is more than just the culmination of a Ph.D. program; it is the product of twenty years of professional experience in outdoor education as well as a dozen years of Scouting before that. As a result, there are decades full of contributors to the ideas presented here. As the Scoutmaster in Troop 38 in Adams, Massachusetts, Don “Bones” Girard has taught the importance of community, responsibility, and a love of adventure to generations of Scouts at the foot of Mount Greylock, including me. John Regentin of the Gettysburg Recreational Adventure Board at Gettysburg College introduced me to the professional world of experiential education when I was a student, teaching me not only the technical skills of backcountry travel, but also the importance of professionalism in the outdoors and the value of a true friend. Dr. Jasper S. Hunt, my graduate school advisor at Minnesota State University-Mankato, showed me the intellectual depth of experiential education. -

Quarterly Newsletter

The Historical Herald Bartlett Historical Society’s summer quarterly newsletter Volume 2 Issue 2 June 2008 -Our Mission- To preserve and protect all documents and items of historic value concerning the history of Bartlett, N H PROGRAMS, PROJECTS -committees: the board is in the process of making appointments to the various AND committees, and they would appreciate PRESENTATIONS member volunteers. -the afghan fundraising project is expected to be underway soon. The society has commissioned Country Mills, Inc. of Pennsylvania to create an afghan which captures the history and spirit of Bartlett’s historic schoolhouses with the depiction of four of the one-room buildings, four of the multi-room buildings and the present school. A sample, along with order blanks, is expected to be on display soon. The audience was then treated to a wonderful slide show presentation entitled “White Mountain Art Heritage,” followed by a time to enjoy the delicious refreshments, and to The Spring Quarterly Meeting view the variety of historical displays drawing attention to the society’s 2008 motto “Celebrating our Historical On Thursday, April 16th members and Heritage.” Also on display was a friends of the Bartlett Historical Society recently-acquired four-page 1816 gathered at the community room at the legislative act giving Bartlett permission Seasons at Attitash for their spring to build a bridge over the Saco, as well quarterly meeting. as an exhibit featuring a newspaper President, Bert George briefly updated account of the flood of 1927, with the audience on the following society photos of the resulting damage in activities: Bartlett village. -

Encyklopédia Kresťanského Umenia

Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia americká architektúra - pozri chicagská škola, prériová škola, organická architektúra, Queen Anne style v Spojených štátoch, Usonia americká ilustrácia - pozri zlatý vek americkej ilustrácie americká retuš - retuš americká americká ruleta/americké zrnidlo - oceľové ozubené koliesko na zahnutej ose, užívané na zazrnenie plochy kovového štočku; plocha spracovaná do čiarok, pravidelných aj nepravidelných zŕn nedosahuje kvality plochy spracovanej kolískou americká scéna - american scene americké architektky - pozri americkí architekti http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:American_women_architects americké sklo - secesné výrobky z krištáľového skla od Luisa Comforta Tiffaniho, ktoré silno ovplyvnili európsku sklársku produkciu; vyznačujú sa jemnou farebnou škálou a novými tvarmi americké litografky - pozri americkí litografi http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:American_women_printmakers A Anne Appleby Dotty Atti Alicia Austin B Peggy Bacon Belle Baranceanu Santa Barraza Jennifer Bartlett Virginia Berresford Camille Billops Isabel Bishop Lee Bontec Kate Borcherding Hilary Brace C Allie máj "AM" Carpenter Mary Cassatt Vija Celminš Irene Chan Amelia R. Coats Susan Crile D Janet Doubí Erickson Dale DeArmond Margaret Dobson E Ronnie Elliott Maria Epes F Frances Foy Juliette mája Fraser Edith Frohock G Wanda Gag Esther Gentle Heslo AMERICKÁ - AMES Strana 1 z 152 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia Charlotte Gilbertson Anne Goldthwaite Blanche Grambs H Ellen Day -

15901 NHCA-Arts Fall02.P65

This issue of NH Arts focuses on individual artists and creativity. According to the U.S. Census, New Hamp- shire is home to about 12,000 artists, which includes arts educators, graphic designers, and architects, as well as creative writers, visual artists, musicians, dancers, actors, and others who derive most of their income from art-making. As you will see on page 9, we have re-instituted an Individual Artist Advisory Committee to help us identify services and programs that best work for all types of artists living in New Hampshire. The committee is reviewing everything from the way we administer artist grants and rosters to the pros and cons of re-instituting an Artist Retreat. We will also be asking the committee to identify the issues, such as housing and health insurance, which most concern New Hampshire artists. Artist Services Coordinator Julie Mento will be taking the committee’s recommendations to the State Arts Councilors during this year for implementation in fiscal years 2004-2005. So if you are an artist and you have some ideas of your own that you would like us to consider, please feel free to contact Julie with your suggestions, [email protected]. Only about 3,000 of New Hampshire’s 12,000 artists have found their way on to the Arts Council’s mailing or e-news lists. Even fewer apply for grants, rosters, or percent for art projects. Although we do not have a great deal of money to give out, we do have a great deal of information on artist resources and can provide ways for New Hampshire artists to connect with each other, strengthening the state’s arts community. -

The Historical Herald PO Box 514 Bartlett, New Hampshire 03812 Www Bartletthistory.Org Bartlett Historical Society’S Newsletter July Issue 2016

1 The Historical Herald PO Box 514 Bartlett, New Hampshire 03812 www BartlettHistory.Org Bartlett Historical Society’s Newsletter July Issue 2016 Our Mission is to preserve and protect all documents and items of historic value concerning the history of Bartlett, New Hampshire President’s Message: Up coming Program Well, it’s official; the Bartlett Historical September 3, 2016 Society has entered into a long term lease of the former St. Joseph’s Catholic Church Peter Huston, “Trail Magic” (the in Bartlett Village from the Bartlett School Emma Gatewood story - 1st District. Although the actual terms of the Woman to Hike Appalachian Trail lease took a while to iron out, all negotia- solo); co-hosted with the AMC at tions were friendly and we cannot thank the Highland Center, 7:30 P.M the members of the Bartlett School Board, SAU 9 Supt. Kevin Richard and Asst. "Trail Magic, The Grandma Gatewood Story" is about Emma Gate- Supt. Kadie Wilson enough for all their wood. She became the face of the Appalachian Trail when at the hard work and professional assistance in age of 67, in 1955, she solo thru-hiked the Appalachian Trail, helping to bring this about. Special recog- which wasn't as widely known as it is now. This amazing feat nition must be given to BHS board mem- transformed her into a national celebrity, as she was the first ber Phil Franklin for his countless hours woman to hike it from end to end. The film is an innovative ap- invested in this undertaking. His proach to documentary and drama story telling, utilizing Emma knowledge and expertise were invaluable Gatewood's journals and diaries to create a first person script pre- to us in helping to finalize the lease. -

May 16, 2013 Free

VOLUME 37, NUMBER 27 MAY 16, 2013 FREE THE WEEKLY NEWS & LIFESTYLE JOURNAL OF MT. WASHINGTON VALLEY Artistic Journeys Benjamin Champney, ‘Dean’ of the White Mountain school Page 2 Valley Feature Behind the scenes at Riverstones Bake Shop Page 3 On the Links “New Boys” take the lead at Wentworth Page 19 A SALMON PRESS PUBLICATION • (603) 447-6336 • PUBLISHED IN CONWAY, NH Artistic Journeys By Cynthia Melendy, Ph.D. State Museum. For those who remark, “Who needs another “A great portion of my art museum?” the answer lies life has been spent in North here, once the artists’ umbrel- Conway and my thoughts la mind is opened. turn pleasantly to that place,” Then, it is always worth- wrote Benjamin Champney in while returning to former his memoirs of his life in Eu- haunts close to home to see rope, North Conway, and the how artists and their friends woods. He is considered the have grown over the seasons. ‘Dean’ of the White Mountain There is always a fresh sur- School of Art, and takes his prise and a welcome regenera- place as the leader of artists in tion when it comes to art. Just the last 150 years of art in the wait a while. Mount Washington Valley. One case in point is the No doubt Champney is a Mount Washington Valley hero to many, and the morn- Arts Association, which is ing the rains came this week, collaborating with the Met to I spent some time in the warm display members’ work in the bluebird skies tracing the Downstairs Gallery as well as march of Spring across the the Upstairs Gallery of the Valley and the Mountains.