Taking the Lead: Women and the White Mountains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Play Fairway Analysis of the Central Cascades Arc-Backarc Regime, Oregon: Preliminary Indications

GRC Transactions, Vol. 39, 2015 Play Fairway Analysis of the Central Cascades Arc-Backarc Regime, Oregon: Preliminary Indications Philip E. Wannamaker1, Andrew J. Meigs2, B. Mack Kennedy3, Joseph N. Moore1, Eric L. Sonnenthal3, Virginie Maris1, and John D. Trimble2 1University of Utah/EGI, Salt Lake City UT 2Oregon State University, College of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences, Corvallis OR 3Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Center for Isotope Geochemistry, Berkeley CA [email protected] Keywords Play Fairway Analysis, geothermal exploration, Cascades, andesitic volcanism, rift volcanism, magnetotellurics, LiDAR, geothermometry ABSTRACT We are assessing the geothermal potential including possible blind systems of the Central Cascades arc-backarc regime of central Oregon through a Play Fairway Analysis (PFA) of existing geoscientific data. A PFA working model is adopted where MT low resistivity upwellings suggesting geothermal fluids may coincide with dilatent geological structural settings and observed thermal fluids with deep high-temperature contributions. A challenge in the Central Cascades region is to make useful Play assessments in the face of sparse data coverage. Magnetotelluric (MT) data from the relatively dense EMSLAB transect combined with regional Earthscope stations have undergone 3D inversion using a new edge finite element formulation. Inversion shows that low resistivity upwellings are associated with known geothermal areas Breitenbush and Kahneeta Hot Springs in the Mount Jefferson area, as well as others with no surface manifestations. At Earthscope sampling scales, several low-resistivity lineaments in the deep crust project from the east to the Cascades, most prominently perhaps beneath Three Sisters. Structural geology analysis facilitated by growing LiDAR coverage is revealing numerous new faults confirming that seemingly regional NW-SE fault trends intersect N-S, Cascades graben- related faults in areas of known hot springs including Breitenbush. -

Spring 2012 Resuscitator — the Camp, Joan Bishop Was a Counselor, and Brooks Van Mudgekeewis Camp for Girls Everen Was a Cook

T H E O H A S S O C I A T I O N 17 Brenner Drive, Newton, New Hampshire 03858 The O H Association is former employees of the AMC Huts System whose activities include sharing sweet White Mountain memories Save the Dates 2012 Details to email later and on website May 19, Cabin Spring Reunion Prepay seafood $30, $15 current croo and kids under 14. Non-seafood is $12, $10 for croo & kids. 12:00 lunch; 4:00 lobster dinner. Walk ins-no lobster. Email Moose Meserve at [email protected] and mail check to 17 Brenner Drive, Newton, NH 03858 Gala, May 22-24 Hut croo training session GreenWool Blanket Vinnie Night, August 18 End of season croo party, Latchstring Award by Caroline Collins I October 10-12, I keep a green wool blanket in the back of my car. It’s Cabin Oktoberfest faded and tattered, but the white AMC logo is still visible. Traditional work for Bavarian victuals feast I tied it to my packboard the last time I hiked out of Carter Email Moose Meserve at [email protected] Notch Hut in the early ’90s. This summer I visited the AMC that you are coming to plan the provisions huts in the White Mountains of New Hampshire after a 22 year absence. My first experience with the Appalachian November 3, Fallfest Mountain Club was whitewater canoeing lessons in Pennsyl- Annual Meeting at vania when I was in high school. My mother was struck with Highland Center inspiration and the next thing I knew we were packing up Details to come camping equipment, canoes and kayaks, and exploring the Potomac, the Shenandoah, the Lehigh, and the Nescopeck rivers among others. -

NYSDEC & AMR Pilot Reservation System

Updated 04/15/21 NYSDEC & AMR Pilot Reservation System DEC and the Adirondack Mountain Reserve (AMR) launched a no-cost pilot reservation system to address public safety at a heavily traveled stretch on Route 73 in the town of Keene in the Adirondack High Peaks. The Adirondack Mountain Reserve is a privately owned 7,000-acre land parcel located in the town of Keene Valley that allows for limited public access through a conservation easement agreement with DEC. The pilot reservation system does not apply to other areas in the Adirondack Park. The reservation system, operated by AMR, will facilitate safer public access to trailheads through the AMR gate and for Noonmark and Round mountains and improve visitors' trip planning and preparation by ensuring they have guaranteed parking upon arrival. In recent years, pedestrian traffic, illegal parking, and roadside stopping along Route 73 have created a dangerous environment for hikers and motorists alike. These no-cost reservations will be required May 1 through Oct. 31, 2021. Reservations will be required for parking, daily access, and overnight access to these specific trails. Visitors can make reservations beginning April 15 at hikeamr.org. Walk-in users without a reservation will not be permitted. o There is no cost associated with making a reservation. o Those arriving to Keene Valley via Greyhound or Trailways bus lines may present a valid bus ticket from within 24 hours of arrival to the AMR parking lot attendant in lieu of a reservation. o Those being dropped off or arriving by bicycle must check in at the AMR Hiker Parking Lot and produce a valid reservation. -

Bill Reightler.Pdf

Hip No. Consigned by Bill Reightler, Agent 1 I Fell for the Pro Raise a Native Mr. Prospector . { Gold Digger Distinctive Pro . Distinctive I Fell for { Well Done . { Fable Effort the Pro . Olden Times Bay mare; Hagley . { Teo Pepi foaled 1995 {I Fell for It . Homing (1989) { Toveris (GB) . { Smeralda (GB) By DISTINCTIVE PRO (1979), black type winner. Sire of 18 crops, 38 black type winners, 438 winners, $33,121,072 in NA/US, $94,025 in Canada, including Quick Mischief [G1] ($608,544), Mellow Roll ($555,772). Sire of dams of black type winners Special Coach, Flying Concert, Deep Gold, Ms Zenna, Bedside Manner, Zennamatic, etc. 1st dam I FELL FOR IT, by Hagley. Winner at 2, $30,715. Dam of 7 foals of racing age, 6 to race, including a 3-year-old of 2003, 5 winners, including-- PHARAOH’S CAT (c. by Sir Cat). 6 wins, 2 to 4, 2003, $94,869, Kimber- lite Pipe S. (KD, $27,000). THAT’S IT DOC (f. by Crafty Prospector). 3 wins at 2, $57,430, Manayunk S. [L] (PHA, $31,890). Iron Pyrite (c. by Strike the Gold). 13 wins, 2 to 7, 2003, $150,603, 3rd Tyro S. [L] (MTH, $6,000). 2nd dam TOVERIS (GB), by Homing. Winner at 2 in England. Dam of 5 winners, including-- MACASO (c. by Ziggy’s Boy). 22 wins in 27 starts, 2 to 5 in Mexico, horse of the year, champion at 2 and 3, champion sprinter, champion handicap horse, Derby Mexicano, etc.; 2 wins, $62,854 in N.A. -

Land Areas of the National Forest System, As of September 30, 2019

United States Department of Agriculture Land Areas of the National Forest System As of September 30, 2019 Forest Service WO Lands FS-383 November 2019 Metric Equivalents When you know: Multiply by: To fnd: Inches (in) 2.54 Centimeters Feet (ft) 0.305 Meters Miles (mi) 1.609 Kilometers Acres (ac) 0.405 Hectares Square feet (ft2) 0.0929 Square meters Yards (yd) 0.914 Meters Square miles (mi2) 2.59 Square kilometers Pounds (lb) 0.454 Kilograms United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Land Areas of the WO, Lands National Forest FS-383 System November 2019 As of September 30, 2019 Published by: USDA Forest Service 1400 Independence Ave., SW Washington, DC 20250-0003 Website: https://www.fs.fed.us/land/staff/lar-index.shtml Cover Photo: Mt. Hood, Mt. Hood National Forest, Oregon Courtesy of: Susan Ruzicka USDA Forest Service WO Lands and Realty Management Statistics are current as of: 10/17/2019 The National Forest System (NFS) is comprised of: 154 National Forests 58 Purchase Units 20 National Grasslands 7 Land Utilization Projects 17 Research and Experimental Areas 28 Other Areas NFS lands are found in 43 States as well as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. TOTAL NFS ACRES = 192,994,068 NFS lands are organized into: 9 Forest Service Regions 112 Administrative Forest or Forest-level units 503 Ranger District or District-level units The Forest Service administers 149 Wild and Scenic Rivers in 23 States and 456 National Wilderness Areas in 39 States. The Forest Service also administers several other types of nationally designated -

Dry River Wilderness

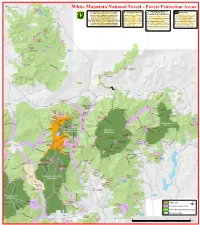

«¬110 SOUTH White Mountain National Forest - Forest Protection Areas POND !5 !B Forest Protection Areas (FPAs) are geographic South !9 Designated Sites !9 The Alpine Zone Wilderness Pond areas where certain activities are restricted to A Rarity in the Northeast Rocky prevent overuse or damage to National Forest Designated sites are campsites or Wilderness Areas are primitive areas Pond resources. Restrictions may include limits on picnic areas within a Forest The alpine zone is a high elevation area in with few signs or other developments. !B camping, use of wood or charcoal fires and Protection area where otherwise which trees are naturally absent or stunted Trails may be rough and difficult to maximum group size. FPAs surround certain features prohibited activities (camping at less that eight feet tall. About 8 square follow. Camping and fires are gererally miles of this habitat exists in the prohibited within 200 feet of any trail W (trails, ponds, parking areas, etc) with either a 200-foot and/or fires) may occur. These e s or ¼ mile buffer. They are marked with signs sites are identified by an official Northeast with most of it over 4000 feet unless at a designated site. No more t M as you enter and exit so keep your eyes peeled. sign, symbol or map. in elevation. Camping is prohibited in the than ten people may occupy a single i la TYPE Name GRID n alpine zone unless there is two or more campsite or hike in the same party. Campgrounds Basin H5 feet of snow. Fires are prohibited at all Big Rock E7 !B Blackberry Crossing G8 ROGERS times. -

As One Who from a Volume Reads: a Study of the Long Narrative Poem in Nineteenth-Century America Sean Leahy University of Vermont

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM Graduate College Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 2019 As One Who From a Volume Reads: A Study of the Long Narrative Poem in Nineteenth-Century America Sean Leahy University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis Recommended Citation Leahy, Sean, "As One Who From a Volume Reads: A Study of the Long Narrative Poem in Nineteenth-Century America" (2019). Graduate College Dissertations and Theses. 1065. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/1065 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate College Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AS ONE WHO FROM A VOLUME READS: A STUDY OF THE LONG NARRATIVE POEM IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY AMERICA A Thesis Presented by Sean Leahy to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Specializing in English May, 2019 Defense Date: March 20, 2019 Thesis Examination Committee: Mary Lou Kete, Ph.D., Advisor Dona Brown, Ph.D., Chairperson Eric Lindstrom, Ph.D. Cynthia J. Forehand, Ph.D., Dean of the Graduate College ABSTRACT Though overlooked and largely unread today, the long narrative poem was a distinct genre available to nineteenth-century American poets. Thematically and formally diverse, the long narrative poem represents a form that poets experimented with and modified, and it accounted for some of the most successful poetry publications in the nineteenth-century United States. -

Research Natural Areas on National Forest System Lands in Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Utah, and Western Wyoming: a Guidebook for Scientists, Managers, and Educators

USDA United States Department of Agriculture Research Natural Areas on Forest Service National Forest System Lands Rocky Mountain Research Station in Idaho, Montana, Nevada, General Technical Report RMRS-CTR-69 Utah, and Western Wyoming: February 2001 A Guidebook for Scientists, Managers, and E'ducators Angela G. Evenden Melinda Moeur J. Stephen Shelly Shannon F. Kimball Charles A. Wellner Abstract Evenden, Angela G.; Moeur, Melinda; Shelly, J. Stephen; Kimball, Shannon F.; Wellner, Charles A. 2001. Research Natural Areas on National Forest System Lands in Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Utah, and Western Wyoming: A Guidebook for Scientists, Managers, and Educators. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-69. Ogden, UT: U.S. Departmentof Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 84 p. This guidebook is intended to familiarize land resource managers, scientists, educators, and others with Research Natural Areas (RNAs) managed by the USDA Forest Service in the Northern Rocky Mountains and lntermountain West. This guidebook facilitates broader recognitionand use of these valuable natural areas by describing the RNA network, past and current research and monitoring, management, and how to use RNAs. About The Authors Angela G. Evenden is biological inventory and monitoring project leader with the National Park Service -NorthernColorado Plateau Network in Moab, UT. She was formerly the Natural Areas Program Manager for the Rocky Mountain Research Station, Northern Region and lntermountain Region of the USDA Forest Service. Melinda Moeur is Research Forester with the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain ResearchStation in Moscow, ID, and one of four Research Natural Areas Coordinators from the Rocky Mountain Research Station. J. Stephen Shelly is Regional Botanist and Research Natural Areas Coordinator with the USDA Forest Service, Northern Region Headquarters Office in Missoula, MT. -

Official List of Public Waters

Official List of Public Waters New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services Water Division Dam Bureau 29 Hazen Drive PO Box 95 Concord, NH 03302-0095 (603) 271-3406 https://www.des.nh.gov NH Official List of Public Waters Revision Date October 9, 2020 Robert R. Scott, Commissioner Thomas E. O’Donovan, Division Director OFFICIAL LIST OF PUBLIC WATERS Published Pursuant to RSA 271:20 II (effective June 26, 1990) IMPORTANT NOTE: Do not use this list for determining water bodies that are subject to the Comprehensive Shoreland Protection Act (CSPA). The CSPA list is available on the NHDES website. Public waters in New Hampshire are prescribed by common law as great ponds (natural waterbodies of 10 acres or more in size), public rivers and streams, and tidal waters. These common law public waters are held by the State in trust for the people of New Hampshire. The State holds the land underlying great ponds and tidal waters (including tidal rivers) in trust for the people of New Hampshire. Generally, but with some exceptions, private property owners hold title to the land underlying freshwater rivers and streams, and the State has an easement over this land for public purposes. Several New Hampshire statutes further define public waters as including artificial impoundments 10 acres or more in size, solely for the purpose of applying specific statutes. Most artificial impoundments were created by the construction of a dam, but some were created by actions such as dredging or as a result of urbanization (usually due to the effect of road crossings obstructing flow and increased runoff from the surrounding area). -

The Proceedings of the Cambridge Historical Society, Volume 11, 1916

The Proceedings of the Cambridge Historical Society, Volume 11, 1916 Table of Contents OFFICERS AND COMMITTEES .......................................................................................5 PROCEEDINGS OF THE THIRTY-SEVENTH TO THIRTY-NINTH MEETINGS .............................................................................................7 PAPERS EXTRACTS FROM LETTERS OF THE REVEREND JOSEPH WILLARD, PRESIDENT OF HARVARD COLLEGE, AND OF SOME OF HIS CHILDREN, 1794-1830 . ..........................................................11 By his Grand-daughter, SUSANNA WILLARD EXCERPTS FROM THE DIARY OF TIMOTHY FULLER, JR., AN UNDERGRADUATE IN HARVARD COLLEGE, 1798- 1801 ..............................................................................................................33 By his Grand-daughter, EDITH DAVENPORT FULLER BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH OF MRS. RICHARD HENRY DANA ....................................................................................................................53 By MRS. MARY ISABELLA GOZZALDI EARLY CAMBRIDGE DIARIES…....................................................................................57 By MRS. HARRIETTE M. FORBES ANNUAL REPORT OF THE TREASURER ........................................................................84 NECROLOGY ..............................................................................................................86 MEMBERSHIP .............................................................................................................89 OFFICERS OF THE SOCIETY -

2Q Outings List Copy

North Woods Chapter 2nd Quarter Outings April 6, Thursday Hike - Cobble Hill Leaders: email your name and telephone number to [email protected] and the leader will contact you We will hike up Cobble Hill overlooking Mirror Lake and the village of Lake Placid. This trail starts from the driveway to Northwoods School off Mirror Lake Drive. We start through the woods and then scramble up an open rock face with views of Mirror Lake, and then back through the woods to the summit. There are good views of the High Peaks and the Lake Placid Horse Show Grounds from the summit. We will descend via an old ski trail. 3 mi. RT Ascent: 450 ft. Class C Limit 12 April 9, Sunday, at 5:00 pm Chapter Meeting and Potluck Supper Presbyterian Church, Church Street, Saranac Lake Program: Frank and Lethe Lescinsky celebrated their 80th birthdays with a 3-generation family gathering in French Polynesia (Tahiti) where they enjoyed partying, hiking, mountain climbing, snorkeling, scuba diving, shopping, and touring; and will illustrate the culture and beauty with pictures distilled from 12 different cameras. Potluck: Hb - M for main dishes, N - Z for salads and A - Ha for desserts, to share with 10 to 12 people. Please remember to bring table service for yourself and for your guests. April 11, Tuesday Hike - Owl’s Head (Long Lake) Leader: email your name and telephone number to [email protected] and the leader will contact you This Owls Head lies west and southwest of Long Lake and Lake Eaton and has a restored fire observation tower. -

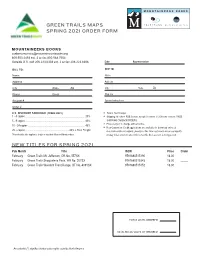

New Titles for Spring 2021 Green Trails Maps Spring

GREEN TRAILS MAPS SPRING 2021 ORDER FORM recreation • lifestyle • conservation MOUNTAINEERS BOOKS [email protected] 800.553.4453 ext. 2 or fax 800.568.7604 Outside U.S. call 206.223.6303 ext. 2 or fax 206.223.6306 Date: Representative: BILL TO: SHIP TO: Name Name Address Address City State Zip City State Zip Phone Email Ship Via Account # Special Instructions Order # U.S. DISCOUNT SCHEDULE (TRADE ONLY) ■ Terms: Net 30 days. 1 - 4 copies ........................................................................................ 20% ■ Shipping: All others FOB Seattle, except for orders of 25 books or more. FREE 5 - 9 copies ........................................................................................ 40% SHIPPING ON BACKORDERS. ■ Prices subject to change without notice. 10 - 24 copies .................................................................................... 45% ■ New Customers: Credit applications are available for download online at 25 + copies ................................................................45% + Free Freight mountaineersbooks.org/mtn_newstore.cfm. New customers are encouraged to This schedule also applies to single or assorted titles and library orders. prepay initial orders to speed delivery while their account is being set up. NEW TITLES FOR SPRING 2021 Pub Month Title ISBN Price Order February Green Trails Mt. Jefferson, OR No. 557SX 9781680515190 18.00 _____ February Green Trails Snoqualmie Pass, WA No. 207SX 9781680515343 18.00 _____ February Green Trails Wasatch Front Range, UT No. 4091SX 9781680515152 18.00 _____ TOTAL UNITS ORDERED TOTAL RETAIL VALUE OF ORDERED An asterisk (*) signifies limited sales rights outside North America. QTY. CODE TITLE PRICE CASE QTY. CODE TITLE PRICE CASE WASHINGTON ____ 9781680513448 Alpine Lakes East Stuart Range, WA No. 208SX $18.00 ____ 9781680514537 Old Scab Mountain, WA No. 272 $8.00 ____ ____ 9781680513455 Alpine Lakes West Stevens Pass, WA No.