Clarence Joe #2 Informant's Address

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early Vancouver Volume Four

Early Vancouver Volume Four By: Major J.S. Matthews, V.D. 2011 Edition (Originally Published 1944) Narrative of Pioneers of Vancouver, BC Collected During 1935-1939. Supplemental to Volumes One, Two and Three collected in 1931-1934. About the 2011 Edition The 2011 edition is a transcription of the original work collected and published by Major Matthews. Handwritten marginalia and corrections Matthews made to his text over the years have been incorporated and some typographical errors have been corrected, but no other editorial work has been undertaken. The edition and its online presentation was produced by the City of Vancouver Archives to celebrate the 125th anniversary of the City's founding. The project was made possible by funding from the Vancouver Historical Society. Copyright Statement © 2011 City of Vancouver. Any or all of Early Vancouver may be used without restriction as to the nature or purpose of the use, even if that use is for commercial purposes. You may copy, distribute, adapt and transmit the work. It is required that a link or attribution be made to the City of Vancouver. Reproductions High resolution versions of any graphic items in Early Vancouver are available. A fee may apply. Citing Information When referencing the 2011 edition of Early Vancouver, please cite the page number that appears at the bottom of the page in the PDF version only, not the page number indicated by your PDF reader. Here are samples of how to cite this source: Footnote or Endnote Reference: Major James Skitt Matthews, Early Vancouver, Vol. 4 (Vancouver: City of Vancouver, 2011), 33. -

The Sinclair Story Sechelt Trade Board Target for Sinclair

I Serving a Progressive and Growing Area on B. C.'s Southern Coast. Cover? Sechelt, Gibsons, Port Mel lon, Woodfibre, Squamish, Irvines Landing, Half Moon Bay, Hardy ty-Law Soon Island, Pender Harbour, Wilson Creek, Roberts Creek, Granthams GIBSONS—A $7000 water pipe Landing, Egmont, Hopkins Landing. purchase bylaw is due to go Brackendale, Cheekeye, Selma Park, PUBLISHED B"? SEE COAST NEWS, _DX_B___Fr2__2_» before ratepayers soon accord etc. '' Business Office: Gibsons, B.C. National Advertisings Office, Powell River, B.C. ing to a decision made by Village Council recently. After several weeks investi Vol. 4 — No.^T, Gibsons, B. C. Monday, April 17, 1950 5c per copy, $2.00 per year, by mail gation, council approved buying =*** the six inch, steel pipe. The money will be repaid from water Women's Institute revenue. In a move to protect future News water-supplies, originating in 20 REGULAR meeting held in the acres owned by >the jam factory, Anglican Hall March 21. Presi council decided to buy outright. dent is Mrs J. Burritt. Members The-suggestion was promoted by repeating the "Ode", 16 mem Mrs E. Nestman as water com bers in attendance. Secretary missioner; "Owing to increase in Mrs W. Haley read correspond population growth, demanding ence. A letter of commendation more water, and the enroachment from provincial supervisor Mrs of logging and clearing opera Stella Gummow, from Batt Mac lntyre, MLA, re hospital scheme tions, this is the best thing to do," GIBSONS:—Tenders for material for the new firehall will be she said. also conveying good wishes for the WI continued success. -

Issue 108.Indd

ARCH GR SE OU E P BRITISH COLUMBIA R POST OFFICE B POSTAL HISTORY R I A IT B ISH COLUM NEWSLETTER Volume 27 Number 4 Whole number 108 December 2018 One-cent Admiral paying domestic postcard rate from Golden to Alberni. Received at the government agent’s office, Alberni, on Sept 11, 1913. A favourite cover from study group member Jim White. on ahead to transfer. We are next.” This black and white viewcard of a steamship The postcard was sent to John (“Jack”) Kirkup, a coming into the wharf at Port Alberni appears to be controversial character from BC’s early history. He cancelled in purple ink with an unlisted homemade was born in Kemptville, Ontario, in 1855, joined the “C+V” (Calgary & Vancouver) straightline device. BC Provincial Police in 1881 and was stationed at “Evidently,” writes Jim, “the regular C&V hammer Yale for five years. Kirkup, who disliked politicians had been lost, stolen or perhaps involved in a train and feuded with the business community, soon wreck. The ‘+’ between the ‘C’ and the ‘V’ would resigned from the force. Later, though, in the mid- normally be an ‘&,’ but I suspect that that would 1890s, he accepted the position of chief constable have been too tough to carve.” and recorder at Rossland, at that time a wild and The sender notes that the train had been stuck sometimes lawless mining town. at Golden for almost 12 hours and had spent the Kirkup was a big man—six foot three and 300 previous day in Revelstoke, where the passengers pounds—and preferred to maintain order with his had seen “all the old-timers.” The writer fists rather than a gun. -

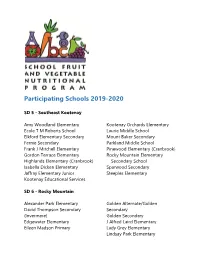

Participating Schools 2019-2020

Participating Schools 2019-2020 SD 5 - Southeast Kootenay Amy Woodland Elementary Kootenay Orchards Elementary Ecole T M Roberts School Laurie Middle School Elkford Elementary Secondary Mount Baker Secondary Fernie Secondary Parkland Middle School Frank J Mitchell Elementary Pinewood Elementary (Cranbrook) Gordon Terrace Elementary Rocky Mountain Elementary Highlands Elementary (Cranbrook) Secondary School Isabella Dicken Elementary Sparwood Secondary Jaffray Elementary Junior Steeples Elementary Kootenay Educational Services SD 6 - Rocky Mountain Alexander Park Elementary Golden Alternate/Golden David Thompson Secondary Secondary (Invermere) Golden Secondary Edgewater Elementary J Alfred Laird Elementary Eileen Madson Primary Lady Grey Elementary Lindsay Park Elementary Martin Morigeau Elementary Open Doors Alternate Education Marysville Elementary Selkirk Secondary McKim Middle School Windermere Elementary Nicholson Elementary SD 8 - Kootenay Lake Adam Robertson Elementary Mount Sentinel Secondary Blewett Elementary School Prince Charles Brent Kennedy Elementary Secondary/Wildflower Program Canyon-Lister Elementary Redfish Elementary School Crawford Bay Elem-Secondary Rosemont Elementary Creston Homelinks/Strong Start Salmo Elementary Erickson Elementary Salmo Secondary Hume Elementary School South Nelson Elementary J V Humphries Trafalgar Middle School Elementary/Secondary W E Graham Community School Jewett Elementary Wildflower School L V Rogers Secondary Winlaw Elementary School SD 10 - Arrow Lakes Burton Elementary School Edgewood -

Blast Rocks Sechelt House Fire Claims Child

Sif^*1*"'' *'?<&* .•'•*vt~ y' »ATIVE LIBRARY ;SS3' £_r1!am©Hi Buildings VidTDRiAj _.C. S<£l/ unexplained Blast rocks Sechelt r A so-far unexplained explosion road near the gouge. No other in the centre of Sechelt around 2:30 damage was caused. a.m. Saturday morning shook peo Members of the RCMP who ple in their.beds and was heard as were in the detachment at the time far away as Davis Bay and Mason the blast occurred immediately Road. went outside and could see a huge puff of smoke on Wharf Road. Besides the sound, which one There was no car or person in view. woman thought was a clap of After investigation it is still thunder striking immediately over unkown what kind of explosive her home until she looked outside device created the blast, although a to discover a lovely starlit night, stick of dynamite is suspected. the only evidence of the blast was a According to Sechelt RCMP gouge approximately 12 inches Constable R.J. Spenard, the per long and three inches wide in the son or persons setting the explosion pavement of Wharf Road in front could be charged with mischief, of Unicorn Pets and Plants. An willful damage and possession of a 18-inch long cord suspected to be weapon dangerous to the public. •; part of a fuse was found on the The investigation continues. , M 13 teachers new to district The grade one to 12 enrollment characteristics of the former Jervis in School District #46 as of Mon Inlet NES Program. day, September 10 was 2,651. -

Lang Urges Second High School for Sechelt-Selma

.-. -*,- . - .=_ 7.(.y-7 \ \ • •••• - •;'-" •'"• ":> ' ~£f': ~i'-'K •. £» *»._ ••'*!!•• West Canadtan/Graphic|industrl<sa .' f 204 West; &tn Av«.. -;'. • :y,'; Viucpuveb 10. 34 C. Service m i * i > •%, On split shiits . ••« ENINSULA StivinB the Sunshine Coast, (Howe Sound to Jervls Inlet), Including Port Mellon, Hopkins Landing, Granthams Landing, Gibsons, Roberts Creak, This Issue 16 Pages — 15c Wilson Creek, Selma Park, Sechelt, Halfmagn Bay, Secret Cdve, Pender Hn>„ Madeira Pork, Garden Boy, Irvine's Londing, Earl Cove, Egmont Union __§•_*> Label ALL Elphinstone students should find ilities at Elphinstone and the elementary and retain their course selection sheets annex can be used on a double, basis, LARGEST CIRCULATION OF ANY PAPER ON THE SOUTHERN SUNSHINE COAST. Vol. 10, No. 35 -- WEDNESDAY, JULY 25, 1973 issued to them during May or June, said greatly reducing the replacement require Don Montgomery, principal, because the ments, Montgomery said. school will open ih September. Students will be able to continue their Four classroom portables will be used course selection made by them during the along with three washroom facilities and spring semester, he continued. Elphin one general office portable. Minimal reno stone WHS nearly destroyed by fire earlier vations will be made to one science lab this month. and preparation room to accommodate the Counsellors will "be available for inter ' home economics department; the annex basement room will be converted to an views the vlast weejt of August It is im portant that students new to the area, art room; the ^arge industrial power shop students whip have failed subjects and will become the resource centre and lib require timetable .changes and students rary.' • " who haveylost their course selection Cleanup, reinstallation and replace sheets see the counsellors. -

Amends Letters Patent of Improvement Districts

PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA ORDER OF THE MINISTER OF MUNICIPAL AFFAIRS AND HOUSING Local Government Act Ministerial Order No. M336 WHEREAS pursuant to the Improvement District Letters Patent Amendment Regulation, B.C. Reg 30/2010 the Local Government Act (the ‘Act’), the minister is authorized to make orders amending the Letters Patent of an improvement district; AND WHEREAS s. 690 (1) of the Act requires that an improvement district must call an annual general meeting at least once in every 12 months; AND WHEREAS the Letters Patent for the improvement districts identified in Schedule 1 further restrict when an improvement district must hold their annual general meetings; AND WHEREAS the Letters Patent for the improvement districts identified in Schedule 1 require that elections for board of trustee positions (the “elections”) must only be held at the improvement district’s annual general meeting; AND WHEREAS the timeframe to hold annual general meetings limits an improvement district ability to delay an election, when necessary; AND WHEREAS the ability of an improvement district to hold an election separately from their annual general meeting increases accessibility for eligible electors; ~ J September 11, 2020 __________________________ ____________________________________________ Date Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing (This part is for administrative purposes only and is not part of the Order.) Authority under which Order is made: Act and section: Local Government Act, section 679 _____ __ Other: Improvement District Letters Patent Amendment Regulation, OIC 50/2010_ Page 1 of 7 AND WHEREAS, I, Selina Robinson, Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing, believe that improvement districts require the flexibility to hold elections and annual general meetings separately and without the additional timing restrictions currently established by their Letters Patent; NOW THEREFORE I HEREBY ORDER, pursuant to section 679 of the Act and the Improvement District Letters Patent Amendment Regulation, B.C. -

2018 General Local Elections

LOCAL ELECTIONS CAMPAIGN FINANCING CANDIDATES 2018 General Local Elections JURISDICTION ELECTION AREA OFFICE EXPENSE LIMIT CANDIDATE NAME FINANCIAL AGENT NAME FINANCIAL AGENT MAILING ADDRESS 100 Mile House 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 Wally Bramsleven Wally Bramsleven 5538 Park Dr 100 Mile House, BC V0K 2E1 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 Leon Chretien Leon Chretien 6761 McMillan Rd Lone Butte, BC V0K 1X3 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 Ralph Fossum Ralph Fossum 5648-103 Mile Lake Rd 100 Mile House, BC V0K 2E1 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 Laura Laing Laura Laing 6298 Doman Rd Lone Butte, BC V0K 1X3 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 Cameron McSorley Cameron McSorley 4481 Chuckwagon Tr PO Box 318 Forest Grove, BC V0K 1M0 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 David Mingo David Mingo 6514 Hwy 24 Lone Butte, BC V0K 1X1 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 Chris Pettman Chris Pettman PO Box 1352 100 Mile House, BC V0K 2E0 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 Maureen Pinkney Maureen Pinkney PO Box 735 100 Mile House, BC V0K 2E0 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 Nicole Weir Nicole Weir PO Box 545 108 Mile Ranch, BC V0K 2Z0 100 Mile House Mayor $10,000.00 Mitch Campsall Heather Campsall PO Box 865 100 Mile House, BC V0K 2E0 100 Mile House Mayor $10,000.00 Rita Giesbrecht William Robertson 913 Jens St PO Box 494 100 Mile House, BC V0K 2E0 100 Mile House Mayor $10,000.00 Glen Macdonald Glen Macdonald 6007 Walnut Rd 100 Mile House, BC V0K 2E3 Abbotsford Abbotsford Councillor $43,928.56 Jaspreet Anand Jaspreet Anand 2941 Southern Cres Abbotsford, BC V2T 5H8 Abbotsford Councillor $43,928.56 Bruce Banman Bruce Banman 34129 Heather Dr Abbotsford, BC V2S 1G6 Abbotsford Councillor $43,928.56 Les Barkman Les Barkman 3672 Fife Pl Abbotsford, BC V2S 7A8 This information was collected under the authority of the Local Elections Campaign Financing Act and the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act. -

REGULAR COUNCIL MEETING HELD in the GEORGE FRASER ROOM, 500 MATTERSON DRIVE Tuesday, March 28, 2017 at 7:30 PM

REGULAR MEETING OF COUNCIL Tuesday, April 11, 2017 @ 7:30 PM George Fraser Room, Ucluelet Community Centre, 500 Matterson Drive, Ucluelet AGENDA Page 1. CALL TO ORDER 2. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF FIRST NATIONS TERRITORY _ Council would like to acknowledge the Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ First Nations on whose traditional territories the District of Ucluelet operates. 3. ADDITIONS TO AGENDA 4. ADOPTION OF MINUTES 4.1. March 28, 2017 Public Hearing Minutes 5 - 7 2017-03-28 Public Hearing Minutes 4.2. March 28, 2017 Regular Minutes 9 - 20 2017-03-28 Regular Minutes 5. UNFINISHED BUSINESS 6. MAYOR’S ANNOUNCEMENTS 7. PUBLIC INPUT, DELEGATIONS & PETITIONS 7.1 Public Input 8. CORRESPONDENCE 8.1. Request re: Potential for Ucluelet Harbour Seaplane Wharf 21 Randy Hanna, Pacific Seaplanes C-1 Pacific Seaplanes 9. INFORMATION ITEMS 9.1. Thank-You and Update on Infinitus Youth Concert 23 West Coast Winter Music Series I-1 West Coast Winter Music Series Update 9.2. Japanese Canadian Historic Places in British Columbia 25 - 28 Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations I-2 Japanese Canadian Historic Places 10. COUNCIL COMMITTEE REPORTS 10.1 Councillor Sally Mole Deputy Mayor April – June Page 2 of 45 • Ucluelet & Area Child Care Society • Westcoast Community Resources Society • Coastal Family Resource Coalition • Food Bank on the Edge • Recreation Commission • Alberni Clayoquot Regional District - Alternate => Other Reports 10.2 Councillor Marilyn McEwen Deputy Mayor July – September • West Coast Multiplex Society • Ucluelet & Area Historical Society • Wild -

Russian American Contacts, 1917-1937: a Review Article

names of individual forts; names of M. Odivetz, and Paul J. Novgorotsev, Rydell, Robert W., All the World’s a Fair: individual ships 20(3):235-36 Visions of Empire at American “Russian American Contacts, 1917-1937: Russian Shadows on the British Northwest International Expositions, 1876-1916, A Review Article,” by Charles E. Coast of North America, 1810-1890: review, 77(2):74; In the People’s Interest: Timberlake, 61(4):217-21 A Study of Rejection of Defence A Centennial History of Montana State A Russian American Photographer in Tlingit Responsibilities, by Glynn Barratt, University, review, 85(2):70 Country: Vincent Soboleff in Alaska, by review, 75(4):186 Ryesky, Diana, “Blanche Payne, Scholar Sergei Kan, review, 105(1):43-44 “Russian Shipbuilding in the American and Teacher: Her Career in Costume Russian Expansion on the Pacific, 1641-1850, Colonies,” by Clarence L. Andrews, History,” 77(1):21-31 by F. A. Golder, review, 6(2):119-20 25(1):3-10 Ryker, Lois Valliant, With History Around Me: “A Russian Expedition to Japan in 1852,” by The Russian Withdrawal From California, by Spokane Nostalgia, review, 72(4):185 Paul E. Eckel, 34(2):159-67 Clarence John Du Four, 25(1):73 Rylatt, R. M., Surveying the Canadian Pacific: “Russian Exploration in Interior Alaska: An Russian-American convention (1824), Memoir of a Railroad Pioneer, review, Extract from the Journal of Andrei 11(2):83-88, 13(2):93-100 84(2):69 Glazunov,” by James W. VanStone, Russian-American Telegraph, Western Union Ryman, James H. T., rev. of Indian and 50(2):37-47 Extension, 72(3):137-40 White in the Northwest: A History of Russian Extension Telegraph. -

Pender Harbour, Wilson Creek, Roberts Creek, Granthams Landing, Ej.N Ontjt__Op-.Ins Landing

Serving a Progressive and Growing Boys, Area on B. C.'s Southern Coast. Covers Sechelt, Gibsons, Port Mel lon, Woodfibre, Squamish, Irvines Landing, Half Moon Bay, Hardy echeli Girls Island, Pender Harbour, Wilson Creek, Roberts Creek, Granthams Landing, Ej.n_ontjT__op-.ins Landing. Brackendale, Cheekeye, etc. PUBLISHTPD BY THE COAST NEWS, LIMITED Win Bali Game Business Office: Sechelt, B.C. National Advertising' Office, Powell River, B.C. THE GIBSON High School boys handed Sechelt High a 9-4 drubbing in an inter-school soft- Vol. Ill No. 43 Sechelt, B. C. Tuesday, May 24, 1949 5c per copy, $2.50 per year, by mail ball game at Sechelt Thursday night. The Sechelt girls avenged the boys' loss, however, by driv- homer to cinch the old ball game, ing heme 14 runs to the Gibsons Dick Clayton starred for the girls' 10. locals with a home run. JamesSutherland Iri the boys' game Pat Slinn The Gibsons girls were spark- was the star for Gibsons, taking ed by the playing of two rookies, over the pitching from Jack Beverly Gray and Grace Grey, Nestman after the fifth inning but were' not strong enough to Of Halfmoon Bag and showing an exhibition of hold the Sechelt fireballs who 1 smart pitching with a change of won quite handily. pace that had the Sechelt boys The girls' game was marred/AT A MEETING of the Gibsons Passes in baffledall the way. In the last by an accident in the lasMialf Board of Trade Wednesday auet will be the hiehlieht of the inning the same Patt Slinn slep- of the last inning when a foul night, C. -

Fishes-Of-The-Salish-Sea-Pp18.Pdf

NOAA Professional Paper NMFS 18 Fishes of the Salish Sea: a compilation and distributional analysis Theodore W. Pietsch James W. Orr September 2015 U.S. Department of Commerce NOAA Professional Penny Pritzker Secretary of Commerce Papers NMFS National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Kathryn D. Sullivan Scientifi c Editor Administrator Richard Langton National Marine Fisheries Service National Marine Northeast Fisheries Science Center Fisheries Service Maine Field Station Eileen Sobeck 17 Godfrey Drive, Suite 1 Assistant Administrator Orono, Maine 04473 for Fisheries Associate Editor Kathryn Dennis National Marine Fisheries Service Offi ce of Science and Technology Fisheries Research and Monitoring Division 1845 Wasp Blvd., Bldg. 178 Honolulu, Hawaii 96818 Managing Editor Shelley Arenas National Marine Fisheries Service Scientifi c Publications Offi ce 7600 Sand Point Way NE Seattle, Washington 98115 Editorial Committee Ann C. Matarese National Marine Fisheries Service James W. Orr National Marine Fisheries Service - The NOAA Professional Paper NMFS (ISSN 1931-4590) series is published by the Scientifi c Publications Offi ce, National Marine Fisheries Service, The NOAA Professional Paper NMFS series carries peer-reviewed, lengthy original NOAA, 7600 Sand Point Way NE, research reports, taxonomic keys, species synopses, fl ora and fauna studies, and data- Seattle, WA 98115. intensive reports on investigations in fi shery science, engineering, and economics. The Secretary of Commerce has Copies of the NOAA Professional Paper NMFS series are available free in limited determined that the publication of numbers to government agencies, both federal and state. They are also available in this series is necessary in the transac- exchange for other scientifi c and technical publications in the marine sciences.