Results of Yangon Writing Workshop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sustaining Progress and Minimising Risks in Myanmar

Myanmar Business Today March 13-19, 2014 mmbiztoday.com mmbiztoday.com MYANMAR’S FIRST BILINGUAL BUSINESS JOURNAL March 13-19, 2014 | Vol 2, Issue 11 6XVWDLQLQJ3URJUHVVDQG0LQLPLVLQJ5LVNVLQ0\DQPDU How to overcome emerging market volatility in Myanmar’s future Dan Steinbock ṘFHUHQWDOUDWHV But could the recent emerging fter half a century of iso- market volatility sweep across lation, Myanmar’s im- the country? Amediate challenge is to sustain reforms, boost foreign Catch-up in the investment and diversify its post-globalisation era industrial base. Unlike other In the next 5-10 years, Myan- Asian tigers, it must cope with mar has potential to evolve into a far more challenging interna- a “mini-BRIC”; that is, a rapidly tional environment. growing large emerging econo- Recent headlines from My- my – but only if it relies on the anmar have caused unease in right growth conditions and can the United States, Europe and sustain the momentum. Japan. While the controversies 6LQFH WDNLQJ ṘFH3UHVLGHQW are social by nature, they have Thein Sein has introduced a indirect economic implications. VODWHRIUHIRUPVDQGVLJQL¿FDQW First, the aid agency Medecins ly improved Myanmar’s ties Sans Frontiers (Doctors With- with Washington and European out Borders) was ordered to countries, which has unleashed Tun/Reuters Soe Zeya cease operations as the Presi- DUDSLGLQÀRZRI:HVWHUQWUDGH GHQW¶V ṘFH DOOHJHG WKDW WKH and investment. The advanced MSF was biased in favour of economies are fascinated with Rakhine’s Muslim Rohingya Myanmar, its population of 60 minority. Then, President him- million people and the last re- self asked parliament to consid- maining emerging economy. In 2012/13, Myanmar’s economy grew at 6.5 percent. -

Behind the Scenes

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 438 Behind the Scenes SEND US YOUR FEEDBACK We love to hear from travellers – your comments keep us on our toes and help make our books better. Our well-travelled team reads every word on what you loved or loathed about this book. Although we cannot reply individually to your submissions, we always guarantee that your feed- back goes straight to the appropriate authors, in time for the next edition. Each person who sends us information is thanked in the next edition – the most useful submissions are rewarded with a selection of digital PDF chapters. Visit lonelyplanet.com/contact to submit your updates and suggestions or to ask for help. Our award-winning website also features inspirational travel stories, news and discussions. Note: We may edit, reproduce and incorporate your comments in Lonely Planet products such as guidebooks, websites and digital products, so let us know if you don’t want your comments reproduced or your name acknowledged. For a copy of our privacy policy visit lonelyplanet.com/ privacy. Tamara Decaluwe, Terence Boley, Thomas Van OUR READERS Loock, Tim Elliott, Ylwa Alwarsdotter Many thanks to the travellers who used the last edition and wrote to us with help- ful hints, useful advice and interesting WRITER THANKS anecdotes: Alex Wharton, Amy Nguyen, Andrew Selth, Simon Richmond Angela Tucker, Anita Kuiper, Annabel Dunn, An- Many thanks to my fellow authors and the fol- nette Lüthi, Anthony Lee, Bernard Keller, Carina lowing people in Yangon: William Myatwunna, Hall, Christina Pefani, Christoph Knop, Chris- Thant Myint-U, Edwin Briels, Jessica Mudditt, toph Mayer, Claudia van Harten, Claudio Strep- Jaiden Coonan, Tim Aye-Hardy, Ben White, parava, Dalibor Mahel, Damian Gruber, David Myo Aung, Marcus Allender, Jochen Meissner, Jacob, Don Stringman, Elisabeth Schwab, Khin Maung Htwe, Vicky Bowman, Don Wright, Elisabetta Bernardini, Erik Dreyer, Florian James Hayton, Jeremiah Whyte and Jon Boos, Gabriella Wortmann, Garth Riddell, Gerd Keesecker. -

Burma (Myanmar)

Burma (Myanmar) January 18-31, 2014 with Chris Leahy If it were possible to design a perfect biological hot spot, one could hardly do better than create a place like Burma (aka Myanmar). Situated on the Tropic of Cancer, bounded by mountain ranges whose highest peak approaches 20,000 feet, combining the floras and faunas of the Indian lowlands, the Himalayas and Indochina as well as its own isolated pockets of endemism, blessed with great rivers and a 1,200 mile long, largely undeveloped coastline, the Texas-sized country contains every Asian habitat except desert. Given these fortunate ecological circumstances, it should not be surprising that Burma contains the greatest diversity of birdlife in Southeast Asia with more than 970 species recorded to date, including four species that occur nowhere else and many more rare, local and spectacular Asian specialties. In addition to these natural treasures, Burma boasts a rich cultural heritage, which, due to both geographical and political isolation, has survived to the modern era in the form of spectacular works of art and architecture and deeply rooted Buddhist philosophy. Unfortunately – as if to counterbalance its immense natural and cultural wealth – Burma has a history marked by tribal and international conflict culminating in one of the world’s most corrupt and repressive governments, which has destroyed the Burmese economy and greatly restricted travel to the country since the 1960’s. Even as travel restrictions were loosened in recent decades, we have hesitated to offer natural history explorations of this biological treasure house, because most of the income generated by foreign visitors flowed into the coffers of the military regime. -

Refugees from Burma Acknowledgments

Culture Profile No. 21 June 2007 Their Backgrounds and Refugee Experiences Writers: Sandy Barron, John Okell, Saw Myat Yin, Kenneth VanBik, Arthur Swain, Emma Larkin, Anna J. Allott, and Kirsten Ewers RefugeesEditors: Donald A. Ranard and Sandy Barron From Burma Published by the Center for Applied Linguistics Cultural Orientation Resource Center Center for Applied Linguistics 4646 40th Street, NW Washington, DC 20016-1859 Tel. (202) 362-0700 Fax (202) 363-7204 http://www.culturalorientation.net http://www.cal.org The contents of this profile were developed with funding from the Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration, United States Department of State, but do not necessarily rep- resent the policy of that agency and the reader should not assume endorsement by the federal government. This profile was published by the Center for Applied Linguistics (CAL), but the opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of CAL. Production supervision: Sanja Bebic Editing: Donald A. Ranard Copyediting: Jeannie Rennie Cover: Burmese Pagoda. Oil painting. Private collection, Bangkok. Design, illustration, production: SAGARTdesign, 2007 ©2007 by the Center for Applied Linguistics The U.S. Department of State reserves a royalty-free, nonexclusive, and irrevocable right to reproduce, publish, or otherwise use, and to authorize others to use, the work for Government purposes. All other rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to the Cultural Orientation Resource Center, Center for Applied Linguistics, 4646 40th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20016. -

Download Itinerary

9 Days Key Site Myanmar 7 Endemic Species Tour Fact Sheet Bird Highlight 7 endemic species White-throated Babbler, Burmese Bushlark, Jerdon’s Minivet, Hooded Treepie, White-browed Nuthatch, Black browed Tit (Burmese Tit) and new one Mt.Victoria Barbax. Habitats Covered Bagan – Semi Desert, scrub, Garden, Open and rice filed Low land forest Irrawady River – Glass land, Sandbar Mt.Victoria – Hill every green forest, mixed oak and rhododendrons, Montane bamboo patches, broad leaf evergreen forest, Pine forest. Expected Climate 5-30 C. winter, 20-40 C. summer Tour pace & walking Moderate and Shoot from a Car, Boat, Hide Accommodation Comfortable hotel & lodges Photographic Opportunities Excellent to Hard Excellent Month November – March Fairly Month April – May Photo Report in Flickr 7 Specie Endemic Specie Click ! WILD BIRD ECO-TOUR THAILAND 9/65 M.10 Soi Chockchai 4 Ladprao Rd. Ladprao Bangkok 10230 Tel.662-931-4154, 661-9210097 Fax.662-514-0232 www.wildbirdeco.net 9 Days Key Site, Myanmar Tour Destination : Yangon – Bagan – Mt.Victoria Duration : 9 days Tour Expect to see : 190 specie + Day 1 : Yangon Tour starts in Yangon after arriving with a morning fight. We will check in a Hotel and get things settled and organized. After lunch we will be sightseeing downtown Yangon. Those who have not been to Myanmar before will visit the famous Shwedagon Pagoda later in the evening. Meal : D Overnight : Myanmar Life Hotel Click ! ( free WIFI ) Day 2 : Yangon > Bagan Early in the morning we will be fying to Bagan, one of the richest archeological sites in South east Asia. We will spend 2 full days in Bagan, You will be birding in ancient ruins more than a thousand years old and will be seeing 4 endemics birds of Burma which are White-throated Babbler, Burmese Bushlark, Jerdon’s Minivet and Hooded Treepie together with other interesting birds. -

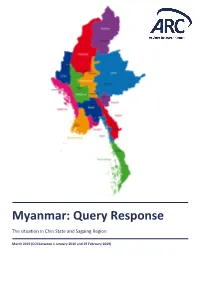

Myanmar: Query Response

Myanmar: Query Response The situation in Chin State and Sagaing Region March 2019 (COI between 1 January 2016 and 19 February 2019) Commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Division of International Protection. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author. © Asylum Research Centre, 2019 ARC publications are covered by the Creative Commons License allowing for limited use of ARC publications provided the work is properly credited to ARC, it is for non-commercial use and it is not used for derivative works. ARC does not hold the copyright to the content of third party material included in this report. Reproduction or any use of the images/maps/infographics included in this report is prohibited and permission must be sought directly from the copyright holder(s). Please direct any comments to [email protected] Cover photo: © Volina/shutterstock.com 2 Contents Explanatory Note ............................................................................................................................ 7 Sources and databases consulted ................................................................................................. 13 List of acronyms ............................................................................................................................ 17 Map of Myanmar .......................................................................................................................... 18 Map of Chin State ........................................................................................................................ -

Balloons Over Bagan

Balloons over Bagan 25th of Nov 2018 morning – Duration 45 min - £250 per person On this unique excursion, the gentle wind will take the role of commander, guiding you through a serene and peaceful sight-seeing journey of Bagan’s temples and landscapes. Your day will begin with an early ride from your hotel on one of the vintage buses dedicated to the journey, and upon arrival to the location, snacks, coffee and tea will be expecting you. As you enjoy the refreshments, you will be able to witness the preparation process of the balloons being inflated. This is followed by a safety briefing and then, at dusk, it is time for take off! The balloons are piloted at no more than 15mph by skilled professionals with years of experience, who also enjoy manipulating the speed/direction strategies of steering the balloon. This experience provides an ever-changing perspective of the archaeological sites and beauty of Bagan you won’t be able to seize otherwise. Please note that due to the limited space in the basket, there are weight and height requirements. After a graceful landing of the balloons, staff will be waiting for you with fresh pastries, fruits, and a glass or two of sparkling wine to conclude this excursion with a celebration of your flight. Weight, height and age requirements Any Passenger in excess of 125 kg / 280 pounds, or any passenger who requires the space in the basket for 2 passengers, will be required to book the additional extra space at the time of booking and pay a 100% surcharge of the ticket price. -

Wildlife Sanctuaries of Thautu and Ciriangtu Location Both Sanctuaries

Wildlife Sanctuaries of Thautu and Ciriangtu Location Both sanctuaries situated in Thantlang Township in the western part of Chin State, Myanmar, near the adjacent to the border of India and Myanmar. Both are located near Thau village, the largest village in the surrounding areas. Both Thautu and Ciriangtu are about 12 miles from the border of India and Burma. Ciriangtu is south of the famous pass "Ruanfiangkuar" (Ruafiang pass) on the famous Saisihchuak Road, which is border's trade road between Myanmar and India. Thautu Wildlife Sanctuary is situated in the border area of Ruakhua village and Thau village. The larger part is in Ruakhua's area. Thautu is connected with Thautlang (Thau-mountain) which is one of the highest peaks in the Chin State. It is about 7,100 feet above sea level (EST). Thautu is between Thautlang and Hmanleknakbo. The name "hmanleknakbo" became a name for a very beautiful and small peak near Thatu where the British army gave a military signal by using the light of a mirror to the British armies who lived in the Headquarter at Hakha camp. Ciriangtu is situated in the bordering area of Thau, Hriangkhan, Tikir and Sialam villages. It is larger than Thautu. It is surrounded by high canyon in the north and south side. The eastern and western parts are very steep too. The best time to visit the sanctuaries is from November to May. June to October is very wet. Jeep or motor cycles are available from Thantlang to Thau. Thatu is about 3 miles and Ciriangtu is about 3.5 miles away from Thau village. -

Title Pilot Biodiversity Assessment of the Hkakabo Razi Passerine

Pilot biodiversity assessment of the Hkakabo Razi passerine avifauna in northern Title Myanmar – implications for conservation from molecular genetics Martin Packert, Christopher M. Milensky, Jochen Martens, Myint Kyaw, Marcela All Authors Suarez- Rubio, Win Naing Thaw, Sai Sein Lin Oo, Hannes Wolfgramm, Swen C. Renner Publication Type International Publication Publisher (Journal name, Bird Conservation International, page 1 of 22 issue no., page no etc.) The Hkakabo Razi region located in northern Myanmar is an Important Bird Area and part of the Eastern Himalayan Biodiversity Hotspot. Within the framework of the World Heritage Convention to enlist the site under criterion (ix) and (x), we conducted a biodiversity assessment for passerine birds using DNA barcoding and other molecular markers. Of the 441 bird species recorded, we chose 16 target species for a comparative phylogeographic study. Genetic analysis was performed for a larger number of species and helped identifying misidentified species. We found phylogeographic structure in all but one of the 16 study species. In 13 Abstract species, populations from northern Myanmar were genetically distinctive and local mitochondrial lineages differed from those found in adjacent regions by 3.9– 9.9% uncorrected genetic distances (cytochrome-b). Since the genetic distinctiveness of study populations will be corroborated by further differences in morphology and song as in other South-East Asian passerines, many of them will be candidates for taxonomic splits, or in case an older taxon name is not available, for the scientific description of new taxa. Considering the short time frame of our study we predict that a great part of undetected faunal diversity in the Hkakabo Razi region will be discovered. -

Myanmar & Nw Thailand

MYANMAR & NW THAILAND: Specialties of Southeast Asia A Tropical Birding Custom Tour January 27 - February 13, 2017 Guide: Ken Behrens All photos by Ken Behrens TOUR SUMMARY Southeast Asia has a complex biogeography, and many birds with restricted distributions. This custom tour was designed around a single client’s “wish list”, which included many of these localized birds, plus a few more widespread Asian species. The trip started as Myanmar-only, but we expanded it to include Thailand when I realized that quite a few of the most-wanted targets were better sought there. Myanmar has opened up to the outside world only in the last 15 years, and although it is developing quickly, it still offers something of a “look back” at what much of the region used to be like. There are already decent roads, lots of domestic flights, and excellent lodges near the major birding sites. The Burmese people are wonderfully warm and hospitable, the landscapes are attractive and distinctive, and the cuisine a savory mix of Indian, Chinese, Thai, and uniquely Burmese components. Myanmar is of major cultural interest, and its top attraction is Bagan, where thousands upon thousands of beautiful temples litter the dusty landscape. This historical and archeological treasure is often placed on par with the much better known Angkor Wat of Cambodia. Myanmar and NW Thailand January 27-February 13, 2017 Myanmar boasts several birds that are endemic to its dry central valley, which has more in common with the Indian subcontinent than the rest of southeast Asia. These are “Burmese” Eurasian Collared-Dove (a likely split), White-throated Babbler, Jerdon’s Minivet (likely to be split or already split depending on your authority), White-throated Babbler is one of the birds that is endemic to Burma’s dry central valley. -

Myanmar Etnico Dal 5 Al 20 Ottobre 2019

MYANMAR ETNICO KHUADO PAWI HARVEST FESTIVAL – PHAUNG DAW Oo PAGODA FESTIVAL - KYAUK TAW GYI PAGODA FESTIVAL DAL 5 AL 20 OTTOBRE 2019 TOUR DI 16 GIORNI IN MYANMAR Il Myanmar, ex Birmania sotto il periodo coloniale inglese, ha una storia molto antica, il cui patrimonio è costituito da differenti tradizioni culturali e religiose che lo rendono unico, insieme all’amalgama di tante etnie che da nord a sud convive in quest’area del Triangolo d’Oro. Il Paese delle Mille Pagode conserva dopo anni di dittaura ancora la sua genuinità; passeggiare lungo le rive dell’Irawwaddy, il fiume più lungo e navigabile, su cui si affacciano i suoi innumerevoli templi, significa conoscere ed esplorare le varie sfaccettature sociali, spirituali e artistiche che compongono il mosaico della Birmania. In questo contesto l’itinerario è approfondito da visite presso aree tribali del North Chin State (con realtà non ancora contaminate dal turismo di massa) e villaggi frequentati da etnie Chin noti per tatuaggi facciali, Pa’O, Bamar, Shan, Intha, Padaung/Giraffa, in coincidenza di Khuado Pawi Harvest Festival, Phaung Daw Oo Pagoda Festival e Kyauk Taw Giyi Pagoda Festival IMPEGNO: Medio con 3 voli interni TIPOLOGIA: etnico, culturale e naturalistico CON ACCOMPAGNATORE DALL’ITALIA UN VIAGGIO RIVOLTO A… Viaggiatori interessati a scoprire una meta genuina, il cui Highlight sono i birmani, popolazione genuina che riesce a coinvolgere il visitatore con il sorriso e la gioia che traspare dai loro volti, affascinando con la cultura del loro paese Il KHUADO PAWI HARVEST FESTIVAL nel North Chin State è considerato nel calendario Zomi (cosidetto Chin) la festa più popolare. -

The Program Tour

Myanmar 12 Days Classic Birding Tour Tour Fact Sheet Bird Highlight 7 endemic specie White-throated Babbler, Burmese Bushlark, Jerdon’s Minivet, Hooded Treepie, White-browed Nuthatch, Black browed Tit (Burmese Tit) and new one Mt.Victoria Barbax. Jerdon's Bushchat, Habitats Covered Bagan – Semi Desert, scrub, Garden, Open and rice filed Low land forest Mt.Victoria – Hill every green forest, mixed oak and rhododendrons, Montane bamboo patches, broad leaf evergreen forest, Pine forest. Kalaw – Hill every green forest, mixed oak Inle lake – Scrub, Water plant, Garden, Glass land Expected Climate Bagan 25-35 C. , Mt.Victoria 5-15 C., Kalaw 20-35 C. Tour pace & walking Moderate Accommodation Comfortable hotel & lodges Photographic Opportunities Excellent Excellent Month November – March Fairly Month April – May Photo Report in Flickr Myanmar birding trip Click ! Myanmar Classic Bird Watching Tour Duration : 12 Days Destination : Yagon – Bagan – Mt.Victoria – Kalaw – Inle Lake Expect to see : 250 sp.+ Day 1 : Yangon - Shwedagon Pagoda The tour starts in Yangon after arriving with a morning fight. We will check in a Hotel and get things settled and organized. After lunch we will be sightseeing downtown Yangon. Those who have not been to Myanmar before will visit the famous Shwedagon Pagoda later in the evening. Meal : D Overnight : Hotel in Yangon WILD BIRD ECO-TOUR 9/65 M.10 Soi Chockchai 4 Ladprao Rd. Ladprao Bangkok 10230 Tel.662-931-4154, 661-9210097 Fax.662-514-0232 www.wildbirdeco.net Day 2 : Yangon > Bagan We will fy to Bagan in the morning (Direct fight from Yangon) After checking in the hotel and having lunch, those who are tired can have an afternoon siesta.