Myanmar the Penal Code

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FATE MANAGEMENT: the Real Target of Modern Criminal Law

FATE MANAGEMENT: The Real Target of Modern Criminal Law W.B. Kennedy Doctor of Juridical Studies 2004 University of Sydney © WB Kennedy, 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT vii PREFACE ix The Thesis History x ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS xiii TABLE OF CASES xv TABLE OF LEGISLATION xix New South Wales xix Other Australian jurisdictions xix Overseas municipal statute xx International instruments xx I INTRODUCTION 1 The Issue 1 The Doctrinal Background 4 The Chosen Paradigm 7 The Hypothesis 9 The Argument 13 Why is This Reform Useful? 21 Methodology 21 Structure ............................................................................24 II ANTICIPATORY OFFENCES 27 Introduction 27 Chapter Goal 28 Conspiracy and Complicity 29 Attempt 31 Arguments for a discount ......................................................33 The restitution argument 33 The prevention argument 34 Arguments for no discount .....................................................35 Punishment as retribution 35 Punishment as prevention 35 The objective argument: punish the violation 35 The subjective argument: punish the person 37 The anti-subjective argument 38 The problems created by the objective approach .......................39 The guilt threshold 39 Unlawful killing 40 Involuntary manslaughter 41 The problems with the subjective approach ..............................41 Impossibility 41 Mistake of fact 42 Mistake of law 43 Recklessness 45 Oppression 47 Conclusion 48 FATE MANAGEMENT III STRICT LIABILITY 51 Introduction 51 Chapter Goal 53 Origins 54 The Nature of Strict Liability -

The Human Right of Self-Defense, 22 BYU J

Brigham Young University Journal of Public Law Volume 22 | Issue 1 Article 3 7-1-2007 The umH an Right of Self-Defense David B. Kopel Paul Gallant Joanne D. Eisen Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/jpl Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, and the Second Amendment Commons Recommended Citation David B. Kopel, Paul Gallant, and Joanne D. Eisen, The Human Right of Self-Defense, 22 BYU J. Pub. L. 43 (2007). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/jpl/vol22/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brigham Young University Journal of Public Law by an authorized editor of BYU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Human Right of Self-Defense David B. Kopel,1 Paul Gallant2 & Joanne D. Eisen3 I. INTRODUCTION “Any law, international or municipal, which prohibits recourse to force, is necessarily limited by the right of self-defense.”4 Is there a human right to defend oneself against a violent attacker? Is there an individual right to arms under international law? Conversely, are governments guilty of human rights violations if they do not enact strict gun control laws? The United Nations and some non-governmental organizations have declared that there is no human right to self-defense or to the possession of defensive arms.5 The UN and allied NGOs further declare that 1. Research Director, Independence Institute, Golden, Colorado; Associate Policy Analyst, Cato Institute, Washington, D.C., http://www.davekopel.org. -

A Rationale of Criminal Negligence Roy Mitchell Moreland University of Kentucky

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 32 | Issue 2 Article 2 1944 A Rationale of Criminal Negligence Roy Mitchell Moreland University of Kentucky Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Torts Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Moreland, Roy Mitchell (1944) "A Rationale of Criminal Negligence," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 32 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol32/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A RATIONALE OF CRIMINAL NEGLIGENCE (Continued from November issue) RoY MOREL A D* 2. METHODS Op DESCRIBING THE NEGLIGENCE REQUIRED 'FOR CRIMINAL LIABILITY The proposed formula for criminal negligence describes the higher degree of negligence required for criminal liability as "conduct creating such an unreasonable risk to life, safety, property, or other interest for the unintentional invasion of which the law prescribes punishment, as to be recklessly disre- gardful of such interest." This formula, like all such machinery, is, of necessity, ab- stractly stated so as to apply to a multitude of cases. As in the case of all abstractions, it is difficult to understand without explanation and illumination. What devices can be used to make it intelligible to judges and juries in individual cases q a. -

Burma's Long Road to Democracy

UNITED STATES InsTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT Priscilla Clapp A career officer in the U.S. Foreign Service, Priscilla Clapp served as U.S. chargé d’affaires and chief of mission in Burma (Myanmar) from June 1999 to August 2002. After retiring from the Foreign Service, she has continued to Burma’s Long Road follow events in Burma closely and wrote a paper for the United States Institute of Peace entitled “Building Democracy in Burma,” published on the Institute’s Web site in July 2007 as Working Paper 2. In this Special to Democracy Report, the author draws heavily on her Working Paper to establish the historical context for the Saffron Revolution, explain the persistence of military rule in Burma, Summary and speculate on the country’s prospects for political transition to democracy. For more detail, particularly on • In August and September 2007, nearly twenty years after the 1988 popular uprising the task of building the institutions for stable democracy in Burma, public anger at the government’s economic policies once again spilled in Burma, see Working Paper 2 at www.usip.org. This into the country’s city streets in the form of mass protests. When tens of thousands project was directed by Eugene Martin, and sponsored by of Buddhist monks joined the protests, the military regime reacted with brute force, the Institute’s Center for Conflict Analysis and Prevention. beating, killing, and jailing thousands of people. Although the Saffron Revolution was put down, the regime still faces serious opposition and unrest. -

Criminal Law -- Homicide -- Application of Felony-Murder Rule When Non-Felon Kills Felon, 34 N.C

NORTH CAROLINA LAW REVIEW Volume 34 | Number 3 Article 10 4-1-1956 Criminal Law -- Homicide -- Application of Felony- Murder Rule When Non-Felon Kills Felon James P. Crews Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation James P. Crews, Criminal Law -- Homicide -- Application of Felony-Murder Rule When Non-Felon Kills Felon, 34 N.C. L. Rev. 350 (1956). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr/vol34/iss3/10 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Law Review by an authorized editor of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NORTH CAROLINA LAW REVIEW (Vol. 34 ideas by words, pictures, or drawings; and that to uphold the Post- master General's revocation would be saying that Congress granted him the power of censorship, or the power to alone determine whether a publication is good or bad for the public to read. This, said the court, would be a radical change from the other standards regarding classifica- tions, and "such a power is so abhorrent to our traditions that it '2 6 should not be easily inferred. The Postmaster General in Esquire relied on the holding of Mil- waukee Publishing Company, but as has been pointed out the matter involved in the latter case was completely nonmailable. It appears then that anything which the Postmaster General may properly declare non- mailable, he may exclude from the second-class without denying mailing privileges entirely, but where the matter involved is mailable he must objectively apply the standards set by Congress. -

Dismantling the Purported Right to Kill in Defence of Property Kenneth Lambeth*

Dismantling the Purported Right to Kill in Defence of Property Kenneth Lambeth* Two of the most fundamental western legal principles are the right to life and the right to own property. But what happens when life and property collide? Such a possibility exists within the realm of criminal law where a person may arguably be acquitted for killing in defence of property. Unlike life, property has never been a fundamental right,1 but a mere privilege2 based upon the power to exclude others. Killing in defence of property, without something more,3 can therefore never be justified. The right to life is now recognised internationally4 as a fundamental human right, that is, a basic right available to all human beings.5 Property is not, nor has it ever been, such a universal right. The common law has developed “without explicit reference to the primacy of the right to life”.6 However, the sanctity of human life, from which the right to life may be said to flow, predates the common law itself. This article examines two main sources to show that, wherever there is conflict between the right to life and the right to property, the right to life must prevail. The first such source is the historical, legal and social * Final year LLB student, Southern Cross University. A sincere and substantial debt of gratitude is owed to Professor Stanley Yeo for his support, guidance and inspiration. 1 The word ‘fundamental’ is defined in the Macquarie Dictionary to mean ‘essential; primary; original’. A ‘right’ is defined as ‘a just claim or title, whether legal, prescriptive or moral’: Delbridge, A et al (eds), The Macquarie Dictionary (3rd Ed), Macquarie Library, NSW, 1998, pp 859, 1830. -

Criminal Code 2003.Pmd 273 11/27/2004, 12:35 PM 274 No

273 No. 9 ] Criminal Code [2004. SAINT LUCIA ______ No. 9 of 2004 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS CHAPTER ONE General Provisions PART I PRELIMINARY Section 1. Short title 2. Commencement 3. Application of Code 4. General construction of Code 5. Common law procedure to apply where necessary 6. Interpretation PART II JUSTIFICATIONS AND EXCUSES 7. Claim of right 8. Consent by deceit or duress void 9. Consent void by incapacity 10. Consent by mistake of fact 11. Consent by exercise of undue authority 12. Consent by person in authority not given in good faith 13. Exercise of authority 14. Explanation of authority 15. Invalid consent not prejudicial 16. Extent of justification 17. Consent to fight cannot justify harm 18. Consent to killing unjustifiable 19. Consent to harm or wound 20. Medical or surgical treatment must be proper 21. Medical or surgical or other force to minors or others in custody 22. Use of force, where person unable to consent 23. Revocation annuls consent 24. Ignorance or mistake of fact criminal code 2003.pmd 273 11/27/2004, 12:35 PM 274 No. 9 ] Criminal Code [2004. 25. Ignorance of law no excuse 26. Age of criminal responsibility 27. Presumption of mental disorder 28. Intoxication, when an excuse 29. Aider may justify same force as person aided 30. Arrest with or without process for crime 31. Arrest, etc., other than for indictable offence 32. Bona fide assistant and correctional officer 33. Bona fide execution of defective warrant or process 34. Reasonable use of force in self-defence 35. Defence of property, possession of right 36. -

Law Culpable Homicide Substantive Criminal

LAW SUBSTANTIVE CRIMINAL LAW CULPABLE HOMICIDE Quadrant-I (B) Description of Module: Description of Module Subject Name Law Paper Name Substantive Criminal Law Module Name/Title Culpable Homicide Not Amounting to Murder Module Id Module 05 Pre-requisites A foundational understanding of the basic principles of criminal law. Objectives To understand culpable homicide and how it differs from murder Keywords Homicide, murder, knowledge Quadrant – II – e-Text CULPABLE HOMICIDE Introduction Some crimes are creations of statutes. These are called statutory offences. Other crimes come from years of judicial decisions together with legal principles founded on Institutional Writers. These are called common law offences. Murder and culpable homicide are both common law offences. Most common law offences require two essential elements before there can be a conviction. There must be a guilty act (called actus reus) and a guilty mind (mens rea). The degree and extent of the guilty mind can vary from crime to crime. For a conviction for any common law offence however there must be some degree of guilty mind (mensrea). Homicide means the killing of a human being by a human being1. Homicide is the highest order of bodily injury that can be inflicted on a human body. Since it is considered as a most serious harm which may be inflicted upon another person, it bags maximum punishment. Under Indian law and US law imposes death penalty2 and in English law proposes mandatory life imprisonment. However in every case of homicide the culprit is not culpable. There may be cases where a law will not punish a man for committing homicide. -

Albin Eser Grounds for Excluding Criminal Responsibility Article 31

Sonderdrucke aus der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg ALBIN ESER Grounds for excluding criminal responsibility [Article 31 of the Rome Statute] Originalbeitrag erschienen in: Otto Triffterer (Hrsg.): Commentary on the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. München [u.a.]: Beck [u.a.], 2008, S. 863-893 ALBIN ESER GROUNDS FOR EXCLUDING CRIMINAL RESPONSIBILITY [Article 31 of the Rome Statute] Reprint from: Otto Triffterer (ed.) Commentary on the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court - Second Edition - C.H. Beck/Munchen • HartiVolkach • Nomos/Baden-Ba,den 2008 Article 31 Grounds for excluding criminal responsibility 1. In addition to other grounds for exc1udin4 criminal responsibility provided for in this Statute, a person shall not be criminally responsible if, at the time of that person's conduct: (a) The person suffers from a mental disease or defect that destroys that person's capacity to appreciate the unlawfulness or nature of his or her conduct, or capacity to control his or her conduct to conform to the requirements of law; (b) The person is in a state of intoxication that destroys that person's capacity to appreciate the unlawfulness or nature of his or her conduct, or capacity to control his or her conduct to conform to the requirements of law, unless the person has become voluntarily intoxicated under such circumstances that the person knew, or disregarded the risk, that, as a result of the intoxication, he or she was likely to engage in conduct constituting a crime within the jurisdiction of the Court; (c) The person acts reasonably to defend himself or herself or another person or, in the case of war crimes, property which Is essential for the survival of the person or another person or property which is essential for accomplishing a military mission, against an imminent and unlawful use of force in a manner proportionate to the degree of danger to the person or the other person or property protected. -

Corporate Criminal Liability for Homicide: Can the Criminal Law Control Corporate Behavior

SMU Law Review Volume 38 Issue 5 Article 5 1984 Corporate Criminal Liability for Homicide: Can the Criminal Law Control Corporate Behavior John E. Stoner Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr Recommended Citation John E. Stoner, Comment, Corporate Criminal Liability for Homicide: Can the Criminal Law Control Corporate Behavior, 38 SW L.J. 1275 (1984) https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol38/iss5/5 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. CORPORATE CRIMINAL LIABILITY FOR HOMICIDE: CAN THE CRIMINAL LAW CONTROL CORPORATE BEHAVIOR? by John E. Stoner ON September 14, 1984, a New Jersey grand jury indicted the Six Flags Corporation on charges of aggravated manslaughter stem- ming from the deaths of eight youths killed in a fire while trapped in one of the park's amusements.' The grand jury also indicted two of the corporation's executives for manslaughter. 2 The indictment marked only the second time that a state has indicted a corporation for any degree of homicide greater than negligent homicide. In the first case an Indiana jury acquitted the Ford Motor Company on three counts of reckless homicide arising out of the deaths of three girls in a Ford Pinto automobile. 3 In addi- tion to these two indictments, in recent years several states have begun to allow the indictment of corporations for lesser degrees of homicide.4 As a result of the increasing number of corporations indicted for homicide and the increasing tendency to charge corporations with other intent offenses, 1. -

1. India and Myanmar: Understanding the Partnership – Sampa Kundu

MYANMAR AND SOUTH ASIA 1. India and Myanmar: Understanding the Partnership – Sampa Kundu, Institute for Defence Studies and Analysis, New Delhi, India; PhD Candidate, School of International Studies, Jawarhalal Nehru University, New Delhi, India Abstract: India’s bilateral relations with Myanmar has raised both optimism and doubts because of a number of ups and downs which portray India’s vague willingness to remain favoured by the Myanmar government and Myanmar’s calculated desire to get advantages from its giant neighbours including India. Scholars and practitioners have explained many times why both India and Myanmar need each other. Some may call it a realist politics and some may call it a fire-brigade alarm politics which implies that both of them act according to the need of the time. The objective of this paper is to explain the necessities of India and Myanmar to each other and how they respond to each other in different times. Connectivity, security, energy and economy are four major pillars of Indo- Myanmar bilateral relationship. Hence, each of these four sectors would have their due share in the proposed paper to illustrate the present dynamics of Indo-Myanmar partnerships. Factors like US, China and the regional cooperation initiatives including ASEAN and BIMSTEC are the external factors that are most likely to shape the future of the Indo-Myanmar relationships. Hence, a simultaneous effort would also be taken to explain the extent of their influence on the same. Based on available primary and secondary literature and field trips, this account will help the readers to contextualise Indo-Myanmar relationship in the light of international relations. -

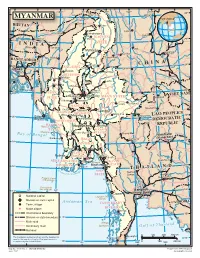

Map of Myanmar

94 96 98 J 100 102 ° ° Indian ° i ° ° 28 n ° Line s Xichang Chinese h a MYANMAR Line J MYANMAR i a n Tinsukia g BHUTAN Putao Lijiang aputra Jorhat Shingbwiyang M hm e ra k Dukou B KACHIN o Guwahati Makaw n 26 26 g ° ° INDIA STATE n Shillong Lumding i w d Dali in Myitkyina h Kunming C Baoshan BANGLADE Imphal Hopin Tengchong SH INA Bhamo C H 24° 24° SAGAING Dhaka Katha Lincang Mawlaik L Namhkam a n DIVISION c Y a uan Gejiu Kalemya n (R Falam g ed I ) Barisal r ( r Lashio M a S e w k a o a Hakha l n Shwebo w d g d e ) Chittagong y e n 22° 22° CHIN Monywa Maymyo Jinghong Sagaing Mandalay VIET NAM STATE SHAN STATE Pongsali Pakokku Myingyan Ta-kaw- Kengtung MANDALAY Muang Xai Chauk Meiktila MAGWAY Taunggyi DIVISION Möng-Pan PEOPLE'S Minbu Magway Houayxay LAO 20° 20° Sittwe (Akyab) Taungdwingyi DEMOCRATIC DIVISION y d EPUBLIC RAKHINE d R Ramree I. a Naypyitaw Loikaw w a KAYAH STATE r r Cheduba I. I Prome (Pye) STATE e Bay Chiang Mai M kong of Bengal Vientiane Sandoway (Viangchan) BAGO Lampang 18 18° ° DIVISION M a e Henzada N Bago a m YANGON P i f n n o aThaton Pathein g DIVISION f b l a u t Pa-an r G a A M Khon Kaen YEYARWARDY YangonBilugyin I. KAYIN ATE 16 16 DIVISION Mawlamyine ST ° ° Pyapon Amherst AND M THAIL o ut dy MON hs o wad Nakhon f the Irra STATE Sawan Nakhon Preparis Island Ratchasima (MYANMAR) Ye Coco Islands 92 (MYANMAR) 94 Bangkok 14° 14° ° ° Dawei (Krung Thep) National capital Launglon Bok Islands Division or state capital Andaman Sea CAMBODIA Town, village TANINTHARYI Major airport DIVISION Mergui International boundary 12° Division or state boundary 12° Main road Mergui n d Secondary road Archipelago G u l f o f T h a i l a Railroad 0 100 200 300 km Chumphon The boundaries and names shown and the designations Kawthuang 10 used on this map do not imply official endorsement or ° acceptance by the United Nations.