Concealment of Birth: Time to Repeal a 200-Year-Old “Convenient Stop-Gap”?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 8 Criminal Conduct Offences

Chapter 8 Criminal conduct offences Page Index 1-8-1 Introduction 1-8-2 Chapter structure 1-8-2 Transitional guidance 1-8-2 Criminal conduct - section 42 – Armed Forces Act 2006 1-8-5 Violence offences 1-8-6 Common assault and battery - section 39 Criminal Justice Act 1988 1-8-6 Assault occasioning actual bodily harm - section 47 Offences against the Persons Act 1861 1-8-11 Possession in public place of offensive weapon - section 1 Prevention of Crime Act 1953 1-8-15 Possession in public place of point or blade - section 139 Criminal Justice Act 1988 1-8-17 Dishonesty offences 1-8-20 Theft - section 1 Theft Act 1968 1-8-20 Taking a motor vehicle or other conveyance without authority - section 12 Theft Act 1968 1-8-25 Making off without payment - section 3 Theft Act 1978 1-8-29 Abstraction of electricity - section 13 Theft Act 1968 1-8-31 Dishonestly obtaining electronic communications services – section 125 Communications Act 2003 1-8-32 Possession or supply of apparatus which may be used for obtaining an electronic communications service - section 126 Communications Act 2003 1-8-34 Fraud - section 1 Fraud Act 2006 1-8-37 Dishonestly obtaining services - section 11 Fraud Act 2006 1-8-41 Miscellaneous offences 1-8-44 Unlawful possession of a controlled drug - section 5 Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 1-8-44 Criminal damage - section 1 Criminal Damage Act 1971 1-8-47 Interference with vehicles - section 9 Criminal Attempts Act 1981 1-8-51 Road traffic offences 1-8-53 Careless and inconsiderate driving - section 3 Road Traffic Act 1988 1-8-53 Driving -

Criminal Law Act 1967 (C

Criminal Law Act 1967 (c. 58) 1 SCHEDULE 4 – Repeals (Obsolete Crimes) Document Generated: 2021-04-04 Status: This version of this schedule contains provisions that are prospective. Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Criminal Law Act 1967, SCHEDULE 4. (See end of Document for details) SCHEDULES SCHEDULE 4 Section 13. REPEALS (OBSOLETE CRIMES) Modifications etc. (not altering text) C1 The text of S. 10(2), S. 13(2), Sch. 2 paras. 3, 4, 6, 10, 12(2), 13(1)(a)(c)(d), 14, Sch. 3 and Sch. 4 is in the form in which it was originally enacted: it was not reproduced in Statutes in Force and does not reflect any amendments or repeals which may have been made prior to 1.2.1991. PART I ACTS CREATING OFFENCES TO BE ABOLISHED Chapter Short Title Extent of Repeal 3 Edw. 1. The Statute of Westminster Chapter 25. the First. (Statutes of uncertain date — Statutum de Conspiratoribus. The whole Act. 20 Edw. 1). 28 Edw. 1. c. 11. (Champerty). The whole Chapter. 1 Edw. 3. Stat. 2 c. 14. (Maintenance). The whole Chapter. 1 Ric. 2. c. 4. (Maintenance) The whole Chapter. 16 Ric. 2. c. 5. The Statute of Praemunire The whole Chapter (this repeal extending to Northern Ireland). 24 Hen. 8. c. 12. The Ecclesiastical Appeals Section 2. Act 1532. Section 4, so far as unrepealed. 25 Hen. 8. c. 19. The Submission of the Clergy Section 5. Act 1533. The Appointment of Bishops Section 6. Act 1533. 25 Hen. 8. c. -

Violence Against the Person

Home Office Counting Rules for Recorded Crime With effect from April 2021 Violence against the Person Homicide Death or Serious Injury – Unlawful Driving Violence with injury Violence without injury Stalking and Harassment All Counting Rules enquiries should be directed to the Force Crime Registrar Home Office Counting Rules for Recorded Crime With effect from April 2021 Homicide Classification Rules and Guidance 1 Murder 4/1 Manslaughter 4/10 Corporate Manslaughter 4/2 Infanticide All Counting Rules enquiries should be directed to the Force Crime Registrar Home Office Counting Rules for Recorded Crime With effect from April 2021 Homicide – Classification Rules and Guidance (1 of 1) Classification: Diminished Responsibility Manslaughter Homicide Act 1957 Sec 2 These crimes should not be counted separately as they will already have been counted as murder (class 1). Coverage Murder Only the Common Law definition applies to recorded crime. Sections 9 and 10 of the Offences against the Person Act 1861 give English courts jurisdiction where murders are committed abroad, but these crimes should not be included in recorded crime. Manslaughter Only the Common Law and Offences against the Person Act 1861 definitions apply to recorded crime. Sections 9 and 10 of the Offences against the Person Act 1861 gives courts jurisdiction where manslaughters are committed abroad, but these crimes should not be included in recorded crime. Legal Definitions Corporate Manslaughter and Homicide Act 2007 Sec 1(1) “1 The offence (1) An organisation to which this section applies is guilty of an offence if the way in which its activities are managed or organised - (a) causes a person’s death, and (b) amounts to a gross breach of a relevant duty of care owed by the organisation to the deceased.” Capable of Being Born Alive - Infant Life (Preservation) Act 1929 Capable of being born alive means capable of being born alive at the time the act was done. -

Cap. 16 Tanzania Penal Code Chapter 16 of the Laws

CAP. 16 TANZANIA PENAL CODE CHAPTER 16 OF THE LAWS (REVISED) (PRINCIPAL LEGISLATION) [Issued Under Cap. 1, s. 18] 1981 PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY THE GOVERNMENT PRINTER, DARES SALAAM Penal Code [CAP. 16 CHAPTER 16 PENAL CODE Arrangement of Sections PARTI General Provisions CHAPTER I Preliminary 1. Short title. 2. Its operation in lieu of the Indian Penal Code. 3. Saving of certain laws. CHAPTER II Interpretation 4. General rule of construction. 5. Interpretation. CHAPTER III Territorial Application of Code 6. Extent of jurisdiction of local courts. 7. Offences committed partly within and partly beyond the jurisdiction, CHAPTER IV General Rules as to Criminal Responsibility 8. Ignorance of law. 9. Bona fide claim of right. 10. Intention and motive. 11. Mistake of fact. 12. Presumption of sanity^ 13. Insanity. 14. Intoxication. 15. Immature age. 16. Judicial officers. 17. Compulsion. 18. Defence of person or property. 18A. The right of defence. 18B. Use of force in defence. 18C. When the right of defence extends to causing abath. 19. Use of force in effecting arrest. 20. Compulsion by husband. 21. Persons not to be punished twice for the same offence. 4 CAP. 16] Penal Code CHAPTER V Parties to Offences 22. Principal offenders. 23. Joint offences. 24. Councelling to commit an offence. CHAPTER VI Punishments 25. Different kinds of punishment. 26. Sentence of death. 27: Imprisonment. 28. Corpora] punishment. 29. Fines. 30. Forfeiture. 31. Compensation. 32. Costs. 33. Security for keeping the peace. 34. [Repealed]. 35. General punishment for misdemeanours. 36. Sentences cumulative, unless otherwise ordered. 37. Escaped convicts to serve unexpired sentences when recap- 38. -

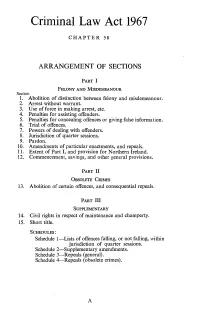

Arrangement of Sections

Criminal Law Act 1967 CHAPTER 58 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Section 1. Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. 2. Arrest without warrant. 3. Use of force in making arrest, etc. 4. Penalties for assisting offenders. 5. Penalties for concealing offences or giving false information. 6. Trial of offences. 7. Powers of dealing with offenders. 8. Jurisdiction of quarter sessions. 9. Pardon. 10. Amendments of particular enactments, and repeals. 11. Extent of Part I, and provision for Northern Ireland. 12. Commencement, savings, and other general provisions. PART 11 OBSOLETE CRIMES 13. Abolition of certain offences, and consequential repeals. PART III SUPPLEMENTARY 14. Civil rights in respect of maintenance and champerty. 15. Short title. SCHEDULES: Schedule 1-Lists of offences falling, or not falling, within jurisdiction of quarter sessions. Schedule 2-Supplementary amendments. Schedule 3-Repeals (general). Schedule 4--Repeals (obsolete crimes). A Criminal Law Act 1967 CH. 58 1 ELIZABETH n , 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] E IT ENACTED by the Queen's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and BTemporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:- PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR 1.-(1) All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are J\b<?liti?n of hereby abolished. -

Criminal Law Act 1967

Status: This version of this Act contains provisions that are prospective. Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Criminal Law Act 1967. (See end of Document for details) Criminal Law Act 1967 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Annotations: Extent Information E1 Subject to s. 11(2)-(4) this Part shall not extend to Scotland or Northern Ireland see s. 11(1) 1 Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. (1) All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are hereby abolished. (2) Subject to the provisions of this Act, on all matters on which a distinction has previously been made between felony and misdemeanour, including mode of trial, the law and practice in relation to all offences cognisable under the law of England and Wales (including piracy) shall be the law and practice applicable at the commencement of this Act in relation to misdemeanour. [F12 Arrest without warrant. (1) The powers of summary arrest conferred by the following subsections shall apply to offences for which the sentence is fixed by law or for which a person (not previously convicted) may under or by virtue of any enactment be sentenced to imprisonment for a term of five years [F2(or might be so sentenced but for the restrictions imposed by 2 Criminal Law Act 1967 (c. -

Suspicious Perinatal Death and the Law: Criminalising Mothers Who Do Not Conform

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Middlesex University Research Repository Suspicious perinatal death and the law: criminalising mothers who do not conform Emma Milne A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Sociology University of Essex 2017 Acknowledgements ii Acknowledgements There are a number of people who have made this PhD possible due to their impact on my life over the course of the period of doctoral study. I would like to take this opportunity to offer my thanks. First and foremost, my parents, Lesley and Nick Milne, for their constant love, friendship, care, commitment to my happiness, and determination that I will achieve my goals and fulfil my dreams. Secondly, Professor Jackie Turton for the decade of encouragement, support (emotional and academic) and friendship, and for persuading me to start the PhD process in the first place. To Professor Pete Fussey and Dr Karen Brennan, for their intellectual and academic support. A number of people have facilitated this PhD through their professional activity. I would like to offer my thanks to all the court clerks in England and Wales who assisted me with access to case files and transcripts – especially the two clerks who trawled through court listings and schedules in order to identify two confidentialised cases for me. Professor Sally Sheldon, and Dr Imogen Jones who provided advice in relation to theory. Ben Rosenbaum and Jason Attermann who helped me decipher the politics of abortion in the US. Michele Hall who has been a constant source of support, information and assistance. -

Table of Contents Topic 1: Principals of Criminal Responsibility

Table of Contents Topic 1: Principals of Criminal Responsibility ................................................................................ 1 Children committing criminal offences ...................................................................................... 1 Doli incapax .................................................................................................................. 1 Evidence that a child knew it was wrong ..................................................................... 1 Corporate Criminal Liability ....................................................................................................... 2 Vicarious Liability .......................................................................................................... 2 Direct Liability ............................................................................................................... 3 Corporate Culture.......................................................................................................... 4 Elements of a Crime ................................................................................................................... 5 The physical elements of a crime ................................................................................. 5 A specified form of conduct ............................................................................... 5 Voluntariness ...................................................................................................... 6 Causation ........................................................................................................... -

Title 17. CRIMES TITLE 17 CRIMES CHAPTER 1

MRS Title 17. CRIMES TITLE 17 CRIMES CHAPTER 1 ABDUCTION §1. Abduction of women (REPEALED) SECTION HISTORY PL 1975, c. 499, §5 (RP). §2. Abduction of women while armed with firearm (REPEALED) SECTION HISTORY PL 1971, c. 539, §1 (NEW). PL 1975, c. 499, §5 (RP). CHAPTER 3 ABORTION; CONCEALMENT OF BIRTH §51. Penalty; attempts (REPEALED) SECTION HISTORY PL 1979, c. 405, §1 (RP). §52. Mother's concealment of death of illegitimate issue (REPEALED) SECTION HISTORY PL 1975, c. 499, §5-A (RP). §53. Contraceptives; miscellaneous information for females (REPEALED) SECTION HISTORY PL 1967, c. 78 (RP). CHAPTER 5 ADULTERY §101. Penalty; cohabitation after divorce (REPEALED) Generated 11.25.2020 Title 17. CRIMES | 1 MRS Title 17. CRIMES SECTION HISTORY PL 1975, c. 499, §5 (RP). CHAPTER 7 ARSON §151. Burning of dwelling house; when murder (REPEALED) SECTION HISTORY PL 1967, c. 410, §1 (RP). §152. Public and private buildings (REPEALED) SECTION HISTORY PL 1967, c. 410, §1 (RP). §153. Other buildings, vessels and bridges (REPEALED) SECTION HISTORY PL 1967, c. 410, §1 (RP). §154. Assault with intent to commit (REPEALED) SECTION HISTORY PL 1967, c. 410, §1 (RP). §155. Produce and trees (REPEALED) SECTION HISTORY PL 1967, c. 410, §1 (RP). §156. Liability of wife (REPEALED) SECTION HISTORY PL 1967, c. 410, §1 (RP). §157. Burning for insurance (REPEALED) SECTION HISTORY PL 1967, c. 410, §1 (RP). CHAPTER 8 ARSON Generated 2 | Title 17. CRIMES 11.25.2020 MRS Title 17. CRIMES §161. First degree (REPEALED) SECTION HISTORY PL 1967, c. 410, §2 (NEW). PL 1975, c. 499, §5 (RP). -

Cases and Materials on Criminal Law

Cases and Materials on Criminal Law Michael T Molan Head ofthe Division ofLaw South Bank University Graeme Broadbent Senior Lecturer in Law Bournemouth University PETMAN PUBLISHING Contents Preface ix Acknowledgements x Table ofcases xi Table of Statutes xxiii 1 External elements of liability 1 Proof - Woolmington v DPP - Criminal Appeal Act 1968 - The nature of external elements - R v Deller - Larsonneur - Liability for omissions - R v Instan - R v Stone and Dobinson - Fagan v Metropolitan Police Commissioner - R v Miller - R v Speck - Causation in law -Äv Pagett - Medical treatment - R v Sw/YA - R v Cheshire - The victim's reaction as a «ovtt.j öcto interveniens — Rv Blaue - R v Williams 2 Fault 21 Intention -Äv Hancock and Shankland - R v Nedrick - Criminal Justice Act 1967 s.8 - Recklessness -fiv Cunningham - R v Caldwell - R v Lawrence - Elliott \ C -R\ Reid -Rv Satnam; R v Kevra/ - Coincidence of acft« re«i and /nens rea - Thabo Meli v R - Transferred malice -Rv Pembliton -Rv Latimer 3 Liability without fault 56 Cundy v Le Cocq - Sherras v De Rutzen - SWef v Parsley - L/OT CA/« /4/£ v R - Gammon Ltd v Attomey-General for Hong Kong - Pharmaceutical Society ofGreat Britain v Storkwain 4 Factors affecting fault 74 Mistake - Mistake of fact negativing fault -Rv Tolson - DPP v Morgan - Mistake as to an excuse or justification - R v Kimber - R v Williams (Gladstone) - Beckford v R - Intoxication - DPP v Majewski - Rv Caldwell - Rv Hardie - R v Woods - R v O'Grady - Mental Disorder - M'Naghten's Case -Rv Kemp - Rv Sullivan - R v Hennessy -

Social Norms and the Law in Reponding to Infanticide Legal

Social Norms and the Law in responding to Infanticide Karen Brennan* Introduction “… I gave birth to a baby in a shed at the back of my house. I don’t know if the baby screamed after birth… I thought the baby was dead[.] I remained in the shed about 10 minutes. There was no move from the baby and I came for a jug of water … and baptised the baby. I took the baby from the shed and put it into a small bag and left it between the river and the roadway at the back of my house. I didn’t harm the child in any way. I put the bag on the floor and laid the baby in it. I folded the bag over it then but if the baby was alive I wouldn’t do that no matter what happened. I came into the kitchen then and washed myself and powdered my face…. I did not put the baby into the river. I didn’t harm the baby in any way.” The above is the statement of an unmarried 22-year-old woman who, in 1953, was convicted of the recently enacted offence of ‘infanticide’ at the Central Criminal Court; she was discharged without sentence.1 The case is a typical example of infanticide in Ireland during the twentieth century, involving a concealed ‘illegitimate’ pregnancy, a secret birth, and ultimately the death of the baby. *Karen Brennan is a lecturer in law at the University of Essex. She wishes to thank Professors Lorna Fox O’Mahony and Sabine Michalowski, and the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful and insightful comments on earlier drafts of this article. -

Criminal Law

The Law Commission (LAW COM. No. 96) CRIMINAL LAW OFFENCES RELATING TO INTERFERENCE WITH THE COURSE OF JUSTICE Laid before Parliament by the Lord High Chancellor pursuant to section 3(2) of the Law Commissions Act 1965 Ordered by The House of Commons to heprinted 7th November 1979 LONDON HER MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE 213 24.50 net k The Law Commission was set up by section 1 of the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law. The Commissioners are- The Honourable Mr. Justice Kerr, Chairman. Mr. Stephen M. Cretney. Mr. Stephen Edell. Mr. W. A. B. Forbes, Q.C. Dr. Peter M. North. The Secretary of the Law Commission is Mr. J. C. R. Fieldsend and its offices are at Conquest House, 37-38 John Street, Theobalds Road, London, WClN 2BQ. 11 THE LAW COMMISSION CRIMINAL LAW CONTENTS Paragraph Page PART I: INTRODUCTION .......... 1.1-1.9 1 PART 11: PERJURY A . PRESENT LAW AND WORKING PAPER PROPOSALS ............. 2.1-2.7 4 1. Thelaw .............. 2.1-2.3 4 2 . The incidence of offences under the Perjury Act 1911 .............. 2.4-2.5 5 3. Working paper proposals ........ 2.6-2.7 7 B . RECOMMENDATIONS AS TO PERJURY IN JUDICIAL PROCEEDINGS ........ 2.8-2.93 8 1. The problem of false evidence not given on oath and the meaning of “judicial proceedings” ............ 2.8-2.43 8 (a) Working paperproposals ...... 2.9-2.10 8 (b) The present law .......... 2.1 1-2.25 10 (i) The Evidence Act 1851. section 16 2.12-2.16 10 (ii) Express statutory powers of tribunals .........