JOHN CROWLEY/BACKGROUND Long a Gene Wolfe Fan, I Was

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Crowley

John Crowley: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator Crowley, John, 1942- Title John Crowley Papers Dates: 1962-2000 Extent 21 boxes, plus 1 print box Abstract: The Crowley papers consist entirely of drafts of his novels, short stories, and scripts for film and television. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-1003 Language English. Access Love & Sleep working notebook and some diaries are restricted. Administrative Information Acquisition Purchases, 1992 (R12762), 1994 (R13316), 2000 (R14699) Processed by Lisa Jones, 2001 Repository: Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin Crowley, John, 1942- Manuscript Collection MS-1003 Biographical Sketch John Crowley, son of Dr. Joseph and Patience Crowley, was born December 1, 1942, in Presque Isle, Maine. He spent his youth in Vermont and Kentucky, attending Indiana University where in 1964 he earned a BA in English with a minor in film and photography. He has since pursued a career as a novelist and documentary writer, the latter in conjunction with his wife, Laurie Block. In 1993, he began teaching courses in Utopian fiction and fiction writing at Yale University. Although Crowley's fiction is frequently categorized as science fiction and fantasy, Gerald Jonas more accurately places him among "writers who feel the need to reinterpret archetypical materials in light of modern experience." Crowley considers only his first three novels to be science fiction. The Deep (1975) and Beasts (1976) take place in futuristic settings, depicting science gone wrong and the individual search for identity and purpose. Engine Summer (1978) amplifies these themes with history, odd lore and arcane knowledge, and extends his work beyond the genre "into the hilly country on the borderline of literature" (Charles Nichol). -

John Crowley Program Guide Program Guide

The conference on imaginative literature, third edition pfcADcTCOn 3 Lowell Hilton, Lowell, Massachusetts March 30 - April 1,1990 GoH: John Crowley Special Guest: Thomas M. Disch Past Master: T. H. White (In Memoriam) Program Guide Introduction and General Information...............2 Hotel Map........................................................... 4 Dealer’s Room Map............................................ 5 Con-At-a-Glance (= Pocket Program)...............6 Guests-At-A-Glance............................................ 9 The Program...................................................... 10 Friday............................................................. 10 Saturday.........................................................12 Sunday........................................................... 17 The Readercon Small Press Award Nominees. 20 About the Program Participants........................24 About Lowell.....................................................33 Help Wanted.....................................................33 Program Guide Page 2 Readercon 3 Introduction Volunteer! Welcome (or welcome back) to Readercon! Like the sf conventions that inspired us, This year, we’ve separated out everything you Readercon is entirely volunteer-run. We need really need to get around into this Program (our hordes of people to help man Registration and Guest material and other essays are now in a Information, keep an eye on the programming, separate Souvenir Book). The fact that this staff the Hospitality Suite, and to do about a Program is bigger than the combined Program I million more things. If interested, ask any Souvenir Book of our last Readercon is an committee member (black or blue ribbon); they’ll indication of how much our programming has point you in the direction of David Walrath, our expanded this time out. We hope you find this Volunteer Coordinator. It’s fun, and, if you work division of information helpful (try to check out enough hours, you earn a free Readercon t-shirt! the Souvenir Book while you’re at it, too). -

SF COMMENTARY 81 40Th Anniversary Edition, Part 2

SF COMMENTARY 81 40th Anniversary Edition, Part 2 June 2011 IN THIS ISSUE: THE COLIN STEELE SPECIAL COLIN STEELE REVIEWS THE FIELD OTHER CONTRIBUTORS: DITMAR (DICK JENSSEN) THE EDITOR PAUL ANDERSON LENNY BAILES DOUG BARBOUR WM BREIDING DAMIEN BRODERICK NED BROOKS HARRY BUERKETT STEPHEN CAMPBELL CY CHAUVIN BRAD FOSTER LEIGH EDMONDS TERRY GREEN JEFF HAMILL STEVE JEFFERY JERRY KAUFMAN PETER KERANS DAVID LAKE PATRICK MCGUIRE MURRAY MOORE JOSEPH NICHOLAS LLOYD PENNEY YVONNE ROUSSEAU GUY SALVIDGE STEVE SNEYD SUE THOMASON GEORGE ZEBROWSKI and many others SF COMMENTARY 81 40th Anniversary Edition, Part 2 CONTENTS 3 THIS ISSUE’S COVER 66 PINLIGHTERS Binary exploration Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) Stephen Campbell Damien Broderick 5 EDITORIAL Leigh Edmonds I must be talking to my friends Patrick McGuire The Editor Peter Kerans Jerry Kaufman 7 THE COLIN STEELE EDITION Jeff Hamill Harry Buerkett Yvonne Rousseau 7 IN HONOUR OF SIR TERRY Steve Jeffery PRATCHETT Steve Sneyd Lloyd Penney 7 Terry Pratchett: A (disc) world of Cy Chauvin collecting Lenny Bailes Colin Steele Guy Salvidge Terry Green 12 Sir Terry at the Sydney Opera House, Brad Foster 2011 Sue Thomason Colin Steele Paul Anderson Wm Breiding 13 Colin Steele reviews some recent Doug Barbour Pratchett publications George Zebrowski Joseph Nicholas David Lake 16 THE FIELD Ned Brooks Colin Steele Murray Moore Includes: 16 Reference and non-fiction 81 Terry Green reviews A Scanner Darkly 21 Science fiction 40 Horror, dark fantasy, and gothic 51 Fantasy 60 Ghost stories 63 Alternative history 2 SF COMMENTARY No. 81, June 2011, 88 pages, is edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough VIC 3088, Australia. -

Locus Awards Schedule

LOCUS AWARDS SCHEDULE WEDNESDAY, JUNE 24 3:00 p.m.: Readings with Fonda Lee and Elizabeth Bear. THURSDAY, JUNE 25 3:00 p.m.: Readings with Tobias S. Buckell, Rebecca Roanhorse, and Fran Wilde. FRIDAY, JUNE 26 3:00 p.m.: Readings with Nisi Shawl and Connie Willis. SATURDAY, JUNE 27 12:00 p.m.: “Amal, Cadwell, and Andy in Conversation” panel with Amal El- Mohtar, Cadwell Turnbull, and Andy Duncan. 1:00 p.m.: “Rituals & Rewards” with P. Djèlí Clark, Karen Lord, and Aliette de Bodard. 2:00 p.m.: “Donut Salon” (BYOD) panel with MC Connie Willis, Nancy Kress, and Gary K. Wolfe. 3:00 p.m.: Locus Awards Ceremony with MC Connie Willis and co-presenter Daryl Gregory. PASSWORD-PROTECTED PORTAL TO ACCESS ALL EVENTS: LOCUSMAG.COM/LOCUS-AWARDS-ONLINE-2020/ KEEP AN EYE ON YOUR EMAIL FOR THE PASSWORD AFTER YOU SIGN UP! QUESTIONS? EMAIL [email protected] LOCUS AWARDS TOP-TEN FINALISTS (in order of presentation) ILLUSTRATED AND ART BOOK • The Illustrated World of Tolkien, David Day (Thunder Bay; Pyramid) • Julie Dillon, Daydreamer’s Journey (Julie Dillon) • Ed Emshwiller, Dream Dance: The Art of Ed Emshwiller, Jesse Pires, ed. (Anthology Editions) • Spectrum 26: The Best in Contemporary Fantastic Art, John Fleskes, ed. (Flesk) • Donato Giancola, Middle-earth: Journeys in Myth and Legend (Dark Horse) • Raya Golden, Starport, George R.R. Martin (Bantam) • Fantasy World-Building: A Guide to Developing Mythic Worlds and Legendary Creatures, Mark A. Nelson (Dover) • Tran Nguyen, Ambedo: Tran Nguyen (Flesk) • Yuko Shimizu, The Fairy Tales of Oscar Wilde, Oscar Wilde (Beehive) • Bill Sienkiewicz, The Island of Doctor Moreau, H.G. -

VI Conclusion

Chapter - VI Conclusion Chapter VI Conclusion Crowley's earliest books—The Deep, Beasts, and Engine Summer (collected as Three Novels)-visit imaginary planets and the far future. In them he comes across as an ambitious author who would merely overheard rumours about science fiction, then decided to put theory into practice. These stories, clever and precious, read like gauzy pencil sketches for his immensely more densely painted large canvases. It seems to be Crowley has used Heroic fantasy in his two novels ‘THE DEEP ’ and ‘ENGINE SUMMER ’ while science fantasy in ‘BEASTS’. ‘The Deep’ and ‘Engine summer’ are based on the heroic characters that work in different way for society. ‘The Deep’ is about the journey of the Visitor from the Sky to the Deep. Visitor, who is a person with fantasy characters, lives with Reds-one of the societies from the plot of ‘The Deep’. On the other hand ‘Engine Summer’ is about a boy namely Rush that speaks who first goes in search of his love-Onee A Day, but finally wanted to become a saint. During his journey he becomes fond of truthful speaking and hence is a hero of society. However, ‘Beasts' is about the genetically engineered animals lion-headed man Painter and fox-headed man Reynard who are trying to survive against hunting and elimination measures of Political forces. The landscape of The Deep is an interesting one. Two societies Reds and Blacks are fighting for the crown while the Just are the criminals and Grays are wise men with justice. The novel shows some sort of war happening between Reds and Black where the hero of the Novel-Visitor tries to solve the problem of crown with the help of Grays. -

An Evening to Honor Gene Wolfe

AN EVENING TO HONOR GENE WOLFE Program 4:00 p.m. Open tour of the Sanfilippo Collection 5:30 p.m. Fuller Award Ceremony Welcome and introduction: Gary K. Wolfe, Master of Ceremonies Presentation of the Fuller Award to Gene Wolfe: Neil Gaiman Acceptance speech: Gene Wolfe Audio play of Gene Wolfe’s “The Toy Theater,” adapted by Lawrence Santoro, accompanied by R. Jelani Eddington, performed by Terra Mysterium Organ performance: R. Jelani Eddington Closing comments: Gary K. Wolfe Shuttle to the Carousel Pavilion for guests with dinner tickets 8:00 p.m Dinner Opening comments: Peter Sagal, Toastmaster Speeches and toasts by special guests, family, and friends Following the dinner program, guests are invited to explore the collection in the Carousel Pavilion and enjoy the dessert table, coffee station and specialty cordials. 1 AN EVENING TO HONOR GENE WOLFE By Valya Dudycz Lupescu A Gene Wolfe story seduces and challenges its readers. It lures them into landscapes authentic in detail and populated with all manner of rich characters, only to shatter the readers’ expectations and leave them questioning their perceptions. A Gene Wolfe story embeds stories within stories, dreams within memories, and truths within lies. It coaxes its readers into a safe place with familiar faces, then leads them to the edge of an abyss and disappears with the whisper of a promise. Often classified as Science Fiction or Fantasy, a Gene Wolfe story is as likely to dip into science as it is to make a literary allusion or religious metaphor. A Gene Wolfe story is fantastic in all senses of the word. -

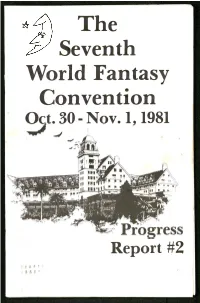

The Convention Itself

The Seventh World Fantasy Convention Oct. 30 - Nov. 1.1981 V ■ /n Jg in iiiWjF. ni III HITV Report #2 I * < ? I fl « f Guests of Honor Alan Garner Brian Frond Peter S. Beagle Master of Ceremonies Karl Edward Wagner Jack Rems, Jeff Frane, Chairmen Will Stone, Art Show Dan Chow, Dealers Room Debbie Notkin, Programming Mark Johnson, Bill Bow and others 1981 World Fantasy Award Nominations Life Achievement: Joseph Payne Brennan Avram Davidson L. Sprague de Camp C. L. Moore Andre Norton Jack Vance Best Novel: Ariosto by Chelsea Quinn Yarbro Firelord by Parke Godwin The Mist by Stephen King (in Dark Forces) The Shadow of the Torturer by Gene Wolfe Shadowland by Peter Straub Best Short Fiction: “Cabin 33” by Chelsea Quinn Yarbro (in Shadows 3) “Children of the Kingdom” by T.E.D. Klein (in Dark Forces) “The Ugly Chickens” by Howard Waldrop (in Universe 10) “Unicorn Tapestry” by Suzy McKee Charnas (in New Dimensions 11) Best Anthology or Collection: Dark Forces ed. by Kirby McCauley Dragons of Light ed. by Orson Scott Card Mummy! A Chrestomathy of Crypt-ology ed. by Bill Pronzini New Terrors 1 ed. by Ramsey Campbell Shadows 3 ed. by Charles L. Grant Shatterday by Harlan Ellison Best Artist: Alicia Austin Thomas Canty Don Maitz Rowena Morrill Michael Whelan Gahan Wilson Special Award (Professional) Terry Carr (anthologist) Lester del Rey (Del Rey/Ballantine Books) Edward L. Ferman (Magazine of Fantasy ir Science Fiction) David G. Hartwell (Pocket/Timescape/Simon & Schuster) Tim Underwood/Chuck Miller (Underwood & Miller) Donald A. Wollheim (DAW Books) Special Award (Non-professional) Pat Cadigan/Arnie Fenner (for Shayol) Charles de Lint/Charles R. -

Ourth Street Antasy Convention

Diana Wynne Jones 1991 Guest of Honor Tom Doherty A convention for students and 1991 Guest Publisher practitioners of the fantasy arts June 21st-23rd, 1991 Previous Guests: at the Roger Zelazny Sheraton Park Place Hotel Thomas Canty Minneapolis, Minnesota Jane Yolen Patricia McKillip Do you like books, thought-provoking panels, and Terri Winching intelligent conversation lasting well into the night? Do you have a special interest in the literature of the Robert Gould fantastic? Do you like good music, good food, and good parties? This is the convention for you! John Crowley Fourth Street is a small convention for people who are David Hartwell serious about good fantasy and good books — serious The Committee: about reading them, serious about writing them, Tim Powers serious about appreciating them in all their various Beth Meacham Chairman, forms. It's also for people who are serious about Registration: having a good time. It's two day of high-quii /, high- David Dyer-Bennet intensity, mind-stretching fun, focused on bo -- no Samuel R. Delany Treasurer, Parties: masquerade, no film or video program, no gi mg. Don Maitz Martin Schafer Hotel: Typical panel topics range from the sublime I the Rob Ihinger frivolous, from the uses of symbolism in fantasy to the Promotion: symbolism of shoes in fantasy, from subtext to Patricia C. Wrede developing taste. The always controversial Moral Programming: Fiction panel is a perennial favorite. Come and argue Steve Brust for yourself! Elise Krueger To pre-register, send your check for $22 to Fourth Street Eileen Lufkin Fantasy Convention, 4242 Minnehaha Avenue South, Art Show: Minneapolis, MN 55406 before June 1st, 1991, or Beth Friedman register at the door for $35. -

Fantastic Fantasy

FANTASTIC FANTASY World Fantasy Award WinnWinninginginging NOVELS Deer Park Public Library 44 Lake Avenue, Deer Park NY 11729 (631) 586-3000 www.deerparklibrary.org 1975: The Forgotten Beasts of Eld by Patricia A. McKillip 1998: The Physiognamy by Jeffrey Ford 1976: Bid Time Return by Richard Matheson 1999: The Antelope Wife by Louise Erdrich 1977: Doctor Rat by William Kotzwinkle 2000: Thraxas by Martin Scott 1978: Our Lady of Darkness by Fritz Leiber 2001: Declare by Tim Powers 1979: Gloriana by Michael Moorcock Galveston by Sean Stewart 1980: Watchtower by Elizabeth A. Lynn 2002: The Other Wind by Ursula Le Guin 1981: The Shadow of the Torturer by Gene Wolfe 2003: The Facts of Life by Graham Joyce 1982: Little Big by John Crowley Ombria in Shadow by Patricia A. McKillip 1983: Nifft the Lean by Michael Shea 2004: Tooth and Claw by Jo Walton 1984: The Dragon Waiting by John M. Ford 2005: Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell by Susanna Clarke 1985: Mythago Wood by Robert Holdstock 2006: Kafka on the Shore by Haruki Murakami 1986: Song of Kali by Dan Simmons 2007: Soldier of Sidon by Gene Wolfe 1987: Perfume by Patrick Suskind 2008: Ysabel by Guy Gavriel Kay 1988: Replay by Ken Grimwood 2009: The Shadow Year by Jeffrey Ford 1989: Koko by Peter Straub Tender Morsels by Margo Lanagan 1990: Lyoness: Madouc by Jack Vance 2010: The City & The City by China Miéville 1991: Only Begotten Daughter by James Morrow 2011: Who Fears Death by Nnedi Okorafor Thomas the Rhymer by Ellen Kushner 2012: Osama by Lavie Tidhar 1992: Boy’s Life by Robert R. -

SF Commentary 96

112211 ppaaggeess AApprriill 22001188 SSFF CCoommmmeennttaarryy 9966 TRIBUTES TO URSULA LE GUIN, KATE WILHELM, PETER NICHOLLS, BRIAN ALDISS 49th Anniversary Edition PETER YOUNG on THE INTERNATIONAL SF DATABASE ANDREW MILNER on GEORGE TURNER RON DRUMMOND on STEVE ERICKSON RAY SINCLAIR-WOOD on SF POETRY COLIN STEELE on THE SF/FANTASY FIELD ANDERS BELLIS GREG BENFORD RANDY BYERS STEPHEN CAMPBELL ELAINE COCHRANE PAUL COLLINS AGNES COSSATO GIAMPAOLO COSSATO ROBERT DAY LEIGH EDMONDS ROB GERRAND BRUCE GILLESPIE TERRY GREEN STEVE JEFFERY CAROL KEWLEY JOHN LITCHEN PATRICK MCGUIRE DENNY MARSHALL MURRAY MOORE GERALD MURNANE TONY PEACEY ANDY ROBSON FRANZ ROTTENSTEINER YVONNE ROUSSEAU SANJAR SIRCAR PAUL SKELTON MARTIN MORSE WOOSTER and many others Cover: Carol Kewley: ‘Utopian Cat’. S F Commentary 96 April 2018 121 pages SF COMMENTARY No. 96, April 2018, is edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough, VIC 3088, Australia. Phone: 61-3-9435 7786. Available only from eFanzines.com: Portrait edition (print page equivalent) at http://efanzines.com/SFC/SFC96P.PDF or Landscape edition (widescreen): at http://efanzines.com/SFC/SFC96L.PDF or from my email address: [email protected] All correspondence: [email protected]. Member fwa. Front cover: Carol Kewley: ‘Utopian Cat’. Back cover: Elaine Cochrane: ‘Untitled (2014).’ Cotton embroidery on linen. Artwork: Irene Pagram (p. 8); Anders Sandberg (pp. 19–20); Denny Marshall (pp. 83, 98, 102, 119); Agnes Cossatto (p. 113). Photographs: Fay Godwin (p. 8); Richard Wilhelm (p. 10); Andrew Porter (p. 12); George Turner Collection (p. 32); Randy Byers (‘King-sized Pine Cones’) (p. 42); Ray Sinclair-Wood (pp. 52, 54, 55, 57, 58, 95); John Litchen (pp. -

Reclaiming the Modern World for the Imagination: Guest of Honor Speech at the 19Th Annual Mythopoeic Conference

Volume 15 Number 2 Article 4 Winter 12-15-1988 Reclaiming the Modern World for the Imagination: Guest of Honor Speech at the 19th Annual Mythopoeic Conference Brian Attebery Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Attebery, Brian (1988) "Reclaiming the Modern World for the Imagination: Guest of Honor Speech at the 19th Annual Mythopoeic Conference," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 15 : No. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol15/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Guest of Honor speech, Mythcon 19. Defines indigenous fantasy—fantasy in a contemporary, “real-world” setting—and illustrates its techniques as demonstrated in Wizard of the Pigeons and Little, Big. -

Reviews: Ed Mcknight Fiction Reviews: Philip Snyder

#257 Mar.-Apr. 2002 Coeditors: Barbara Lucas Shelley Rodrigo Blanchard Nonfiction Reviews: Ed McKnight Fiction Reviews: Philip Snyder The SFRAReview (ISSN IN THIS ISSUE: 1068-395X) is published six times a year by the Science Fiction Research Association (SFRA) and distributed SFRA Business to SFRA members.NONNON Individual issues are not for sale; however, starting with Candidates Statements 2 issue #256, all issues will be pub- Clareson Award Presentation lished to SFRA’s website no less than Speech 2001 4 two months after paper publication. For information about the SFRA and its benefits, see the description at the Non Fiction Reviews back of this issue. For a membership A. E. van Vogt 6 application, contact SFRA Treasurer Being Gardner Dozoiz 7 Dave Mead or get one from the SFRA website: <www.sfra.org>. Tolkien’s Art & The Lord of the Rings 9 Star Trek: The Human Frontier 11 SUBMISSIONS Star Trek and Sacred Ground 12 The SFRAReview editors encourage submissions, including essays, review Interacting with Babylon 5 13 essays that cover several related texts, Science Fiction Cinema 14 and interviews. Please send submis- What If? 2 15 sions or queries to both coeditors. If you would like to review nonfiction The Horror Genre 17 or fiction, please contact the Fantasy of the 20th Century 18 respective editor and/or email [email protected] [email protected][email protected]. Fiction Reviews Barbara Lucas, Coeditor Jenna Starborn 19 1352 Fox Run Drive, Suite 206 Picoverse 19 Willoughby, OH 44094 Picoverse 19 <[email protected]> Ombria in Shadow 20 Mars Probes 22 Shelley Rodrigo Blanchard, Coeditor 6842 S.