SF Commentary 68

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SF Commentary 41-42

S F COMMENTARY 41/42 Brian De Palma (dir): GET TO KNOW YOUR RABBIT Bruce Gillespie: I MUST BE TALKING TO MY FRIENDS (86) . ■ (SFC 40) (96) Philip Dick (13, -18-19, 37, 45, 66, 80-82, 89- Bruce Gillespie (ed): S F COMMENTARY 30/31 (81, 91, 96-98) 95) Philip Dick: AUTOFAC (15) Dian Girard: EAT, DRINK AND BE MERRY (64) Philip Dick: FLOW MY TEARS THE POLICEMAN SAID Victor Gollancz Ltd (9-11, 73) (18-19) Paul Goodman (14). Gordon Dickson: THINGS WHICH ARE CAESAR'S (87) Giles Gordon (9) Thomas Disch (18, 54, 71, 81) John Gordon (75) Thomas Disch: EMANCIPATION (96) Betsey & David Gorman (95) Thomas Disch: THE RIGHT WAY TO FIGURE PLUMBING Granada Publishing (8) (7-8, 11) Gunter Grass: THE TIN DRUM (46) Thomas Disch: 334 (61-64, 71, 74) Thomas Gray: ELEGY WRITTEN IN A COUNTRY CHURCH Thomas Disch: THINGS LOST (87) YARD (19) Thomas Disch: A VACATION ON EARTH (8) Gene Hackman (86) Anatoliy Dneprov: THE ISLAND OF CRABS (15) Joe Haldeman: HERO (87) Stanley Donen (dir): SINGING IN THE RAIN (84- Joe Haldeman: POWER COMPLEX (87) 85) Knut Hamsun: MYSTERIES (83) John Donne (78) Carey Handfield (3, 8) Gardner Dozois: THE LAST DAY OF JULY (89) Lee Harding: FALLEN SPACEMAN (11) Gardner Dozois: A SPECIAL KIND OF MORNING (95- Lee Harding (ed): SPACE AGE NEWSLETTER (11) 96) Eric Harries-Harris (7) Eastercon 73 (47-54, 57-60, 82) Harry Harrison: BY THE FALLS (8) EAST LYNNE (80) Harry Harrison: MAKE ROOM! MAKE ROOM! (62) Heinz Edelman & George Dunning (dirs): YELLOW Harry Harrison: ONE STEP FROM EARTH (11) SUBMARINE (85) Harry Harrison & Brian Aldiss (eds): THE -

13Th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture

13th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture James F. O’Gorman Non-fiction 38.65 ACROSS THE SEA OF GREGORY BENFORD SF 9.95 SUNS Affluent Society John Kenneth Galbraith 13.99 African Exodus: The Origins Christopher Stringer and Non-fiction 6.49 of Modern Humanity Robin McKie AGAINST INFINITY GREGORY BENFORD SF 25.00 Age of Anxiety: A Baroque W. H. Auden Eclogue Alabanza: New and Selected Martin Espada Poetry 24.95 Poems, 1982-2002 Alexandria Quartet Lawrence Durell ALIEN LIGHT NANCY KRESS SF Alva & Irva: The Twins Who Edward Carey Fiction Saved a City And Quiet Flows the Don Mikhail Sholokhov Fiction AND ETERNITY PIERS ANTHONY SF ANDROMEDA STRAIN MICHAEL CRICHTON SF Annotated Mona Lisa: A Carol Strickland and Non-fiction Crash Course in Art History John Boswell From Prehistoric to Post- Modern ANTHONOLOGY PIERS ANTHONY SF Appointment in Samarra John O’Hara ARSLAN M. J. ENGH SF Art of Living: The Classic Epictetus and Sharon Lebell Non-fiction Manual on Virtue, Happiness, and Effectiveness Art Attack: A Short Cultural Marc Aronson Non-fiction History of the Avant-Garde AT WINTER’S END ROBERT SILVERBERG SF Austerlitz W.G. Sebald Auto biography of Miss Jane Ernest Gaines Fiction Pittman Backlash: The Undeclared Susan Faludi Non-fiction War Against American Women Bad Publicity Jeffrey Frank Bad Land Jonathan Raban Badenheim 1939 Aharon Appelfeld Fiction Ball Four: My Life and Hard Jim Bouton Time Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues Barefoot to Balanchine: How Mary Kerner Non-fiction to Watch Dance Battle with the Slum Jacob Riis Bear William Faulkner Fiction Beauty Robin McKinley Fiction BEGGARS IN SPAIN NANCY KRESS SF BEHOLD THE MAN MICHAEL MOORCOCK SF Being Dead Jim Crace Bend in the River V. -

John Crowley

John Crowley: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator Crowley, John, 1942- Title John Crowley Papers Dates: 1962-2000 Extent 21 boxes, plus 1 print box Abstract: The Crowley papers consist entirely of drafts of his novels, short stories, and scripts for film and television. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-1003 Language English. Access Love & Sleep working notebook and some diaries are restricted. Administrative Information Acquisition Purchases, 1992 (R12762), 1994 (R13316), 2000 (R14699) Processed by Lisa Jones, 2001 Repository: Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin Crowley, John, 1942- Manuscript Collection MS-1003 Biographical Sketch John Crowley, son of Dr. Joseph and Patience Crowley, was born December 1, 1942, in Presque Isle, Maine. He spent his youth in Vermont and Kentucky, attending Indiana University where in 1964 he earned a BA in English with a minor in film and photography. He has since pursued a career as a novelist and documentary writer, the latter in conjunction with his wife, Laurie Block. In 1993, he began teaching courses in Utopian fiction and fiction writing at Yale University. Although Crowley's fiction is frequently categorized as science fiction and fantasy, Gerald Jonas more accurately places him among "writers who feel the need to reinterpret archetypical materials in light of modern experience." Crowley considers only his first three novels to be science fiction. The Deep (1975) and Beasts (1976) take place in futuristic settings, depicting science gone wrong and the individual search for identity and purpose. Engine Summer (1978) amplifies these themes with history, odd lore and arcane knowledge, and extends his work beyond the genre "into the hilly country on the borderline of literature" (Charles Nichol). -

SF Commentary 83

SSFF CCoommmmeennttaarryy 8833 October 2012 GUY SALVIDGE ON THE NOVELS OF PHILIP K. DICK ALSO IN THIS ISSUE: Brian ALDISS Eric MAYER John BAXTER Cath ORTLIEB Greg BENFORD Rog PEYTON Helena BINNS Mark PLUMMER Damien BRODERICK Franz ROTTENSTEINER Ned BROOKS Yvonne ROUSSEAU Ian COVELL David RUSSELL Bruce GILLESPIE Darrell SCHWEITZER Fenna HOGG Steve SNEYD John-Henri HOLMBERG Ian WATSON Carol KEWLEY Taral WAYNE Robert LICHTMAN Frank WEISSENBORN Patrick MCGUIRE Ray WOOD Murray MACLACHLAN Martin Morse WOOSTER Tim MARION Cover: Fenna Hogg S F Commentary 83 SF Commentary No 83, October 2012, 107 pages, is edited and published by Bruce Gillespie ([email protected]), 5 Howard St., Greensborough VIC 3088, Australia, and http://efanzines.com/SFC/SFC83.pdf. All correspondence: [email protected]. Member fwa. First edition and primary publication is electronic. All material in this publication was contributed for one-time use only, and copyrights belong to the contributors. Alternate editions: * A very limited number of print copies are available. Enquiries to the editor. * The alternate PDF version is portrait-shaped, i.e. it looks the same as the print edition, but with colour graphics. Front cover: Melbourne graphic artist Fenna Hogg’s cover does not in fact portray Philip K. Dick wearing a scramble suit. That’s what it looks like to me. It is actually based on a photograph of Melbourne writer and teacher Steve Cameron, who arranged with Fenna for its use as a cover. Graphic: Carol Kewley (p. 105). Photographs: Damien Broderick (p. 5); Guy Salvidge (p. 10); Jim Sakland/Dick Eney (p. 67); Jerry Bauer (p. -

Catalogue XV 116 Rare Works of Speculative Fiction

Catalogue XV 116 Rare Works Of Speculative Fiction About Catalogue XV Welcome to our 15th catalogue. It seems to be turning into an annual thing, given it was a year since our last catalogue. Well, we have 116 works of speculative fiction. Some real rarities in here, and some books that we’ve had before. There’s no real theme, beyond speculative fiction, so expect a wide range from early taproot texts to modern science fiction. Enjoy. About Us We are sellers of rare books specialising in speculative fiction. Our company was established in 2010 and we are based in Yorkshire in the UK. We are members of ILAB, the A.B.A. and the P.B.F.A. To Order You can order via telephone at +44(0) 7557 652 609, online at www.hyraxia.com, email us or click the links. All orders are shipped for free worldwide. Tracking will be provided for the more expensive items. You can return the books within 30 days of receipt for whatever reason as long as they’re in the same condition as upon receipt. Payment is required in advance except where a previous relationship has been established. Colleagues – the usual arrangement applies. Please bear in mind that by the time you’ve read this some of the books may have sold. All images belong to Hyraxia Books. You can use them, just ask us and we’ll give you a hi-res copy. Please mention this catalogue when ordering. • Toft Cottage, 1 Beverley Road, Hutton Cranswick, UK • +44 (0) 7557 652 609 • • [email protected] • www.hyraxia.com • Aldiss, Brian - The Helliconia Trilogy [comprising] Spring, Summer and Winter [7966] London, Jonathan Cape, 1982-1985. -

Science Fiction Review 28 Geis 1978-11

NOVEMBER-DECEMBER 1978 NUMBER 28 SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW $1.50 Interview: C.J. CHERRYH BEYOND GENOCIDE By DAMON KNIGHT ONE IMMORTAL MAN ——————— . SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW rO^Ona, U Formerly THE ALIEN CRITIC RICHARD E. GEIS, editor & publisher November, 1978 — Vol,7, No, 5 PUBLISHED BI-MONTHLY COVER BY BRUCE CONKLIN WHOLE NUMBER 28 JML , MARCH, MAY, JULY, SEPT., NOV. From an idea by Richard 3, Gels FHUNE.: (303) 282-©%! SINGLE COPY %\3i) ALIEN THOUGHTS by the editor. .4 BEYOND GENOCIDE by damon knight. 8 REVIEWS THE CARTOON HISTORY OF THE JOHNNY WI RECUTTER a poem UNIVERSE ..35 DR, STRANGE 7 BY NEAL WILGUS II ANTHOLOGY SPECULATIVE NIGHTFALL (RECORD) .18 OF POETRY #3 INTERVIEW WITH C.J. CHERRYH IMMORTAL 22 locus 23 TABU SPANISH OF MEXICO CONDUCTED . BY GALE BURNICK., .14 THE WHOLE FANZINE CATALOG #2 COLD FEAR * « • • < * • • * 1 23 TALES FROM GAVAGAN's BAR ..24 THRUST #11 HE HEARS, . , . NIGHTFALL BY ISAAC - DRACULA S DOG ........... i... .... ASIMOV. EXTRAPOLATION, AN SF NEWS ATTACK OF THE KILLER TOMATOES .... REVIEWED BY MARK MANSELL, 18 LETTER.......... 24 BIG PLANET 24 HALLOWEEN LEONORA THE HUMAN HOTLINE LORD FOUL S BANE 25 WHO GOES THERE? 25 PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK elliott, , . .19 SF News by elton t. THE BOYS FROM PURSUIT OF THE SCREAMER .......... ,25 BRAZIL WATERSHIP DOWN THE VIVISECTOR a column AN EXERCISE FOR MADMEN 26 CONFESSIONS OF A CRAP ARTIST .... .63 BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER .22 EMPTY WORLD ...26 BEASTS 27 OTHER VOICES book reviews by THE YEAR'S BEST HORROR ORSON SCOTT CARD, BILL GLASS, STORIES, SERIES VI 27 INTERIOR ART PAUL MCGUIRE III, FRED PATTEN, SPLINTER OF THE MIND'S EYE ..... -

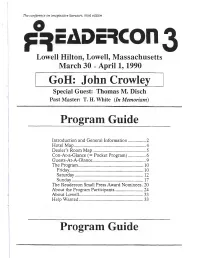

John Crowley Program Guide Program Guide

The conference on imaginative literature, third edition pfcADcTCOn 3 Lowell Hilton, Lowell, Massachusetts March 30 - April 1,1990 GoH: John Crowley Special Guest: Thomas M. Disch Past Master: T. H. White (In Memoriam) Program Guide Introduction and General Information...............2 Hotel Map........................................................... 4 Dealer’s Room Map............................................ 5 Con-At-a-Glance (= Pocket Program)...............6 Guests-At-A-Glance............................................ 9 The Program...................................................... 10 Friday............................................................. 10 Saturday.........................................................12 Sunday........................................................... 17 The Readercon Small Press Award Nominees. 20 About the Program Participants........................24 About Lowell.....................................................33 Help Wanted.....................................................33 Program Guide Page 2 Readercon 3 Introduction Volunteer! Welcome (or welcome back) to Readercon! Like the sf conventions that inspired us, This year, we’ve separated out everything you Readercon is entirely volunteer-run. We need really need to get around into this Program (our hordes of people to help man Registration and Guest material and other essays are now in a Information, keep an eye on the programming, separate Souvenir Book). The fact that this staff the Hospitality Suite, and to do about a Program is bigger than the combined Program I million more things. If interested, ask any Souvenir Book of our last Readercon is an committee member (black or blue ribbon); they’ll indication of how much our programming has point you in the direction of David Walrath, our expanded this time out. We hope you find this Volunteer Coordinator. It’s fun, and, if you work division of information helpful (try to check out enough hours, you earn a free Readercon t-shirt! the Souvenir Book while you’re at it, too). -

SF COMMENTARY 81 40Th Anniversary Edition, Part 2

SF COMMENTARY 81 40th Anniversary Edition, Part 2 June 2011 IN THIS ISSUE: THE COLIN STEELE SPECIAL COLIN STEELE REVIEWS THE FIELD OTHER CONTRIBUTORS: DITMAR (DICK JENSSEN) THE EDITOR PAUL ANDERSON LENNY BAILES DOUG BARBOUR WM BREIDING DAMIEN BRODERICK NED BROOKS HARRY BUERKETT STEPHEN CAMPBELL CY CHAUVIN BRAD FOSTER LEIGH EDMONDS TERRY GREEN JEFF HAMILL STEVE JEFFERY JERRY KAUFMAN PETER KERANS DAVID LAKE PATRICK MCGUIRE MURRAY MOORE JOSEPH NICHOLAS LLOYD PENNEY YVONNE ROUSSEAU GUY SALVIDGE STEVE SNEYD SUE THOMASON GEORGE ZEBROWSKI and many others SF COMMENTARY 81 40th Anniversary Edition, Part 2 CONTENTS 3 THIS ISSUE’S COVER 66 PINLIGHTERS Binary exploration Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) Stephen Campbell Damien Broderick 5 EDITORIAL Leigh Edmonds I must be talking to my friends Patrick McGuire The Editor Peter Kerans Jerry Kaufman 7 THE COLIN STEELE EDITION Jeff Hamill Harry Buerkett Yvonne Rousseau 7 IN HONOUR OF SIR TERRY Steve Jeffery PRATCHETT Steve Sneyd Lloyd Penney 7 Terry Pratchett: A (disc) world of Cy Chauvin collecting Lenny Bailes Colin Steele Guy Salvidge Terry Green 12 Sir Terry at the Sydney Opera House, Brad Foster 2011 Sue Thomason Colin Steele Paul Anderson Wm Breiding 13 Colin Steele reviews some recent Doug Barbour Pratchett publications George Zebrowski Joseph Nicholas David Lake 16 THE FIELD Ned Brooks Colin Steele Murray Moore Includes: 16 Reference and non-fiction 81 Terry Green reviews A Scanner Darkly 21 Science fiction 40 Horror, dark fantasy, and gothic 51 Fantasy 60 Ghost stories 63 Alternative history 2 SF COMMENTARY No. 81, June 2011, 88 pages, is edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough VIC 3088, Australia. -

Selected Scifi 201102.Xlsx

Selected Used SciFi Books- Subject to availability - Call/email store to receive purchasing link ([email protected] 540206-2505) StorePri AuthorsLast Title EAN Publisher ce Cross-Currents: Storm Season, The Face of Chaos, Abbey, Robert Lynn Asprin and Lynn B000GPXLOQ Nelson Doubleday,. $8.00 and Wings of Omen Adams, Douglas Life, The Universe and Everything 9780517548745 Harmony Books $8.00 Adams, Douglas Mostly Harmless 9781127539635 BALLANTINE BOOKS $15.00 Adams, Douglas So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish 9780795326516 HARMONY BOOKS $6.00 Adams, Douglas The Restaurant at the End of the Universe 9780517545355 Harmony $8.00 Adams, Richard MAIA 9780394528571 Knopf $8.00 Alan, Foster Dean Midworld B001975ZFI Ballentine $8.00 Aldiss, Brian W. Helliconia Summer (Helliconia Trilogy, Book Two) 9781111805173 Atheneum / $8.00 Aldiss, Brian W. Non-Stop B0057JRIV8 Carroll & Graf $10.00 Aldiss, Brian Wilson Helliconia Winter (Helliconia, 3) 9780689115417 Atheneum $7.00 Allen, Roger E. Isaac Asimov's Inferno 9780441000234 Ace Trade $6.00 Allen, Roger Macbride Isaac Asimov's Utopia 9781857982800 Orion Publishing Co $8.00 Allston, Aaron Enemy lines (Star wars, The new Jedi order) 9780739427774 Science Fiction $15.00 Anderson, Kevin J and Rebecca The Rise of the Shadow Academy 9781568652115 Guild America $15.00 Moesta Anderson, Kevin J,Herbert, Brian Hunters of Dune 9780765312921 Tor Books $10.00 Anderson, Kevin J. A Forest of Stars: The Saga of Seven Suns Book 2 9780446528719 Aspect $8.00 Anderson, Kevin J. Darksaber (Star Wars) 9780553099744 Spectra $10.00 Anderson, Kevin J. Hidden Empire: The Saga of Seven Suns - Book 1 9780446528627 Aspect $8.00 Anderson, Kevin J. -

Locus Awards Schedule

LOCUS AWARDS SCHEDULE WEDNESDAY, JUNE 24 3:00 p.m.: Readings with Fonda Lee and Elizabeth Bear. THURSDAY, JUNE 25 3:00 p.m.: Readings with Tobias S. Buckell, Rebecca Roanhorse, and Fran Wilde. FRIDAY, JUNE 26 3:00 p.m.: Readings with Nisi Shawl and Connie Willis. SATURDAY, JUNE 27 12:00 p.m.: “Amal, Cadwell, and Andy in Conversation” panel with Amal El- Mohtar, Cadwell Turnbull, and Andy Duncan. 1:00 p.m.: “Rituals & Rewards” with P. Djèlí Clark, Karen Lord, and Aliette de Bodard. 2:00 p.m.: “Donut Salon” (BYOD) panel with MC Connie Willis, Nancy Kress, and Gary K. Wolfe. 3:00 p.m.: Locus Awards Ceremony with MC Connie Willis and co-presenter Daryl Gregory. PASSWORD-PROTECTED PORTAL TO ACCESS ALL EVENTS: LOCUSMAG.COM/LOCUS-AWARDS-ONLINE-2020/ KEEP AN EYE ON YOUR EMAIL FOR THE PASSWORD AFTER YOU SIGN UP! QUESTIONS? EMAIL [email protected] LOCUS AWARDS TOP-TEN FINALISTS (in order of presentation) ILLUSTRATED AND ART BOOK • The Illustrated World of Tolkien, David Day (Thunder Bay; Pyramid) • Julie Dillon, Daydreamer’s Journey (Julie Dillon) • Ed Emshwiller, Dream Dance: The Art of Ed Emshwiller, Jesse Pires, ed. (Anthology Editions) • Spectrum 26: The Best in Contemporary Fantastic Art, John Fleskes, ed. (Flesk) • Donato Giancola, Middle-earth: Journeys in Myth and Legend (Dark Horse) • Raya Golden, Starport, George R.R. Martin (Bantam) • Fantasy World-Building: A Guide to Developing Mythic Worlds and Legendary Creatures, Mark A. Nelson (Dover) • Tran Nguyen, Ambedo: Tran Nguyen (Flesk) • Yuko Shimizu, The Fairy Tales of Oscar Wilde, Oscar Wilde (Beehive) • Bill Sienkiewicz, The Island of Doctor Moreau, H.G. -

SF Commentary 106

SF Commentary 106 May 2021 80 pages A Tribute to Yvonne Rousseau (1945–2021) Bruce Gillespie with help from Vida Weiss, Elaine Cochrane, and Dave Langford plus Yvonne’s own bibliography and the story of how she met everybody Perry Middlemiss The Hugo Awards of 1961 Andrew Darlington Early John Brunner Jennifer Bryce’s Ten best novels of 2020 Tony Thomas and Jennifer Bryce The Booker Awards of 2020 Plus letters and comments from 40 friends Elaine Cochrane: ‘Yvonne Rousseau, 1987’. SSFF CCOOMMMMEENNTTAARRYY 110066 May 2021 80 pages SF COMMENTARY No. 106, May 2021, is edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough, VIC 3088, Australia. Email: [email protected]. Phone: 61-3-9435 7786. .PDF FILE FROM EFANZINES.COM. For both print (portrait) and landscape (widescreen) editions, go to https://efanzines.com/SFC/index.html FRONT COVER: Elaine Cochrane: Photo of Yvonne Rousseau, at one of those picnics that Roger Weddall arranged in the Botanical Gardens, held in 1987 or thereabouts. BACK COVER: Jeanette Gillespie: ‘Back Window Bright Day’. PHOTOGRAPHS: Jenny Blackford (p. 3); Sally Yeoland (p. 4); John Foyster (p. 8); Helena Binns (pp. 8, 10); Jane Tisell (p. 9); Andrew Porter (p. 25); P. Clement via Wikipedia (p. 46); Leck Keller-Krawczyk (p. 51); Joy Window (p. 76); Daniel Farmer, ABC News (p. 79). ILLUSTRATION: Denny Marshall (p. 67). 3 I MUST BE TALKING TO MY FRIENDS, PART 1 34 TONY THOMAS TO MY FRIENDS, PART 1 THE BOOKER PRIZE 2020 READING EXPERIENCE 3, 7 41 JENNIFER BRYCE A TRIBUTE TO YVONNNE THE 2020 BOOKER PRIZE -

Helliconia Summer (1983) Chapter Three Helliconia Summer (1983)

CHAPTER THREE HELLICONIA SUMMER (1983) CHAPTER THREE HELLICONIA SUMMER (1983) Helliconia Summer (1983) is the second novel in the Helliconia Trilogy. It is about a planet part of a binary star system, whose seasons are centuries long. Helliconia Spring (1982) is the first novel in this series which covers hundreds of years but Helliconia Summer spans only six months. It examines in depth, the breakdown of the relationship between the King and the Queen of Borlien. The King is struggling to maintain control of his country and to solidify relations between Borlien and Oldorando. In the book Helliconia Summer (1983), there are two plots; the main plot is related to the king. The king Jandol Anganol is struggling with his weakening power over events in his life and his country. The king was defeated in Cosgatt War so he wants to regain his power. The king wants to make friendship with the king of Oldorando. For the sake of the country he is ready to divorce his beautiful queen Myrdemlnggala and then he is ready to marry Simoda Tal, the princess of Oldorando kingdom. After divorce the king wants to marry Simoda Tal but uncertainty the princess was killed by RobaydayAnganol, the prince of Borlien. The king was very disappointed because the death of the princess. But he is also ready to marry Milua Tal, another princess of Oldorando kingdom. The king JandolAnganol marries Milua Tal, nine and half year old princess of Oldorando. The King is phagor lover because so many phagor slaves working in his army. Yuli, a phagor is the king's pet.