Tales Newly Told

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congratulations Susan & Joost Ueffing!

CONGRATULATIONS SUSAN & JOOST UEFFING! The Staff of the CQ would like to congratulate Jaguar CO Susan and STARFLEET Chief of Operations Joost Ueffi ng on their September wedding! 1 2 5 The beautiful ceremony was performed OCT/NOV in Kingsport, Tennessee on September 2004 18th, with many of the couple’s “extended Fleet family” in attendance! Left: The smiling faces of all the STARFLEET members celebrating the Fugate-Ueffi ng wedding. Photo submitted by Wade Olsen. Additional photos on back cover. R4 SUMMIT LIVES IT UP IN LAS VEGAS! Right: Saturday evening banquet highlight — commissioning the USS Gallant NCC 4890. (l-r): Jerry Tien (Chief, STARFLEET Shuttle Ops), Ed Nowlin (R4 RC), Chrissy Killian (Vice Chief, Fleet Ops), Larry Barnes (Gallant CO) and Joe Martin (Gallant XO). Photo submitted by Wendy Fillmore. - Story on p. 3 WHAT IS THE “RODDENBERRY EFFECT”? “Gene Roddenberry’s dream affects different people in different ways, and inspires different thoughts... that’s the Roddenberry Effect, and Eugene Roddenberry, Jr., Gene’s son and co-founder of Roddenberry Productions, wants to capture his father’s spirit — and how it has touched fans around the world — in a book of photographs.” - For more info, read Mark H. Anbinder’s VCS report on p. 7 USPS 017-671 125 125 Table Of Contents............................2 STARFLEET Communiqué After Action Report: R4 Conference..3 Volume I, No. 125 Spies By Night: a SF Novel.............4 A Letter to the Fleet........................4 Published by: Borg Assimilator Media Day..............5 STARFLEET, The International Mystic Realms Fantasy Festival.......6 Star Trek Fan Association, Inc. -

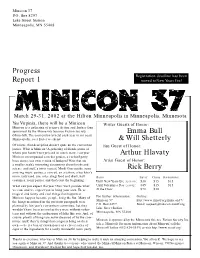

Progress Report 1 Emma Bull & Will Shetterly Arthur Hlavaty Rick

Minicon 37 P.O. Box 8297 Lake Street Station Minneapolis, MN 55408 Progress Re g i s t r ation deadline has been Report 1 mo ved toNew Years Eve! M a rch 29-31, 2002 at the Hilton Minneapolis in Minneapolis, Minnesota Yes Virginia, there will be a Minicon Writer Guests of Honor: Minicon is a gathering of science fiction and fantasy fans sponsored by the Minnesota Science Fiction Society Emma Bull (Minn-StF). The convention is held each year in (or near) Minneapolis, over Easter weekend. &Will Shetterly Of course, that description doesn't quite do the conven t i o n Fan Guest of Honor: justice. What is Minicon? A gathering of friends (some of whom you haven't met yet) and so much more. Last yea r Arthur Hlavaty Minicon encompassed a rocket garden, a cocktail party, bozo noses, our own version of Ju n k yard War s (but on Artist Guest of Honor: a smaller scale), interesting discussions about books and science and stuff, a trivia contest, Mardi Gras masks, some Rick Berry amazing music parties, a concert, an art show, a hucks t e r ' s room, tasty (and, um, interesting) food and drink, hall RATES: ADULT CHILD SUPPORTING costumes, room parties, and that's just the beginning. Until New Years Eve (1 2 / 3 1 / 0 1 ) : $3 0 $1 5 $1 5 What can you expect this year? Fun: we'll provide wha t Until Valentines Day (2 / 1 4 / 0 2 ) : $4 5 $1 5 $1 5 we can, and we expect you to bring your own. -

John Crowley

John Crowley: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator Crowley, John, 1942- Title John Crowley Papers Dates: 1962-2000 Extent 21 boxes, plus 1 print box Abstract: The Crowley papers consist entirely of drafts of his novels, short stories, and scripts for film and television. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-1003 Language English. Access Love & Sleep working notebook and some diaries are restricted. Administrative Information Acquisition Purchases, 1992 (R12762), 1994 (R13316), 2000 (R14699) Processed by Lisa Jones, 2001 Repository: Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin Crowley, John, 1942- Manuscript Collection MS-1003 Biographical Sketch John Crowley, son of Dr. Joseph and Patience Crowley, was born December 1, 1942, in Presque Isle, Maine. He spent his youth in Vermont and Kentucky, attending Indiana University where in 1964 he earned a BA in English with a minor in film and photography. He has since pursued a career as a novelist and documentary writer, the latter in conjunction with his wife, Laurie Block. In 1993, he began teaching courses in Utopian fiction and fiction writing at Yale University. Although Crowley's fiction is frequently categorized as science fiction and fantasy, Gerald Jonas more accurately places him among "writers who feel the need to reinterpret archetypical materials in light of modern experience." Crowley considers only his first three novels to be science fiction. The Deep (1975) and Beasts (1976) take place in futuristic settings, depicting science gone wrong and the individual search for identity and purpose. Engine Summer (1978) amplifies these themes with history, odd lore and arcane knowledge, and extends his work beyond the genre "into the hilly country on the borderline of literature" (Charles Nichol). -

DECK the FRIDGE with SHEETS of EINBLATT, FA LA LA LA LA JANUARY 1991 DEC 29 (Sat): Minn-STF Meeting. 1:30 Pm On, at Home of Herm

DECK THE FRIDGE WITH SHEETS OF EINBLATT, FA LA LA LA LA JANUARY 1991 DEC 29 (Sat): Minn-STF Meeting. 1:30 pm on, at home of Herman Schouten and Gerri Balter and more than one stuffed animal / 1381 N. Pascal Street (St. Paul). No smoking; house is not childproofed. FFI: 646-3852. DEC 31 (Mon): New Year's Eve party. 3:30 pm until next year, at home of Jerry Corwin and Julie Johnson / 3040 Grand Avenue S. (Mpls). Cats; no smoking; house is not childproofed. FFI: 824-7800. JAN 1 (Tue): New Year's Day Open House. 2 to 9 pm, at home of Carol Kennedy and Jonathan Adams / 3336 Aldrich Avenue S. (Mpls). House is described as "child-proofed, more or less." Cats. No smoking. FFI: 823-2784. 5 (Sat): Stipple-Apa 88 collation. 2 pm, at home of Joyce Maetta Odum / 2929 32nd Avenue S. (Mpls). Copy count is 32. House is childproofed. No smoking. FFI: 729-6577 (Maetta) or 331-3655 (Stipple OK Peter). 6 (Sun): Ladies' Sewing Circle and Terrorist Society. 2 pm on, at home of Jane Strauss / 3120 3rd Avenue S. (Mpls). Childproofed. FFI: 827-6706. 12 (Sat): Minn-STF Meeting. 1:30 pm on, at home of Marianne Hageman and Mike Dorn / 2965 Payne Avenue (Little Canada). No smoking. Not childproofed. "Believable numbers of huggable stuffed animals." FFI: 483-3422. 12 (Sat): Minneapa 261 collation. 2 pm, at the Minn-STF Meeting. Copy count is 30. Believable numbers of apahacks. FFI: OE Dean Gahlon at 827-1775. 12 (Sat): World Building Group of MIFWA meets at 1 pm at Apache Wells Saloon / Apache Plaza / 37th Avenue and Silver Lake Road (St. -

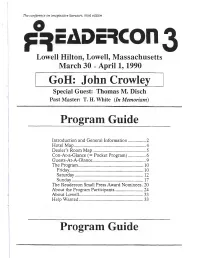

John Crowley Program Guide Program Guide

The conference on imaginative literature, third edition pfcADcTCOn 3 Lowell Hilton, Lowell, Massachusetts March 30 - April 1,1990 GoH: John Crowley Special Guest: Thomas M. Disch Past Master: T. H. White (In Memoriam) Program Guide Introduction and General Information...............2 Hotel Map........................................................... 4 Dealer’s Room Map............................................ 5 Con-At-a-Glance (= Pocket Program)...............6 Guests-At-A-Glance............................................ 9 The Program...................................................... 10 Friday............................................................. 10 Saturday.........................................................12 Sunday........................................................... 17 The Readercon Small Press Award Nominees. 20 About the Program Participants........................24 About Lowell.....................................................33 Help Wanted.....................................................33 Program Guide Page 2 Readercon 3 Introduction Volunteer! Welcome (or welcome back) to Readercon! Like the sf conventions that inspired us, This year, we’ve separated out everything you Readercon is entirely volunteer-run. We need really need to get around into this Program (our hordes of people to help man Registration and Guest material and other essays are now in a Information, keep an eye on the programming, separate Souvenir Book). The fact that this staff the Hospitality Suite, and to do about a Program is bigger than the combined Program I million more things. If interested, ask any Souvenir Book of our last Readercon is an committee member (black or blue ribbon); they’ll indication of how much our programming has point you in the direction of David Walrath, our expanded this time out. We hope you find this Volunteer Coordinator. It’s fun, and, if you work division of information helpful (try to check out enough hours, you earn a free Readercon t-shirt! the Souvenir Book while you’re at it, too). -

SF COMMENTARY 81 40Th Anniversary Edition, Part 2

SF COMMENTARY 81 40th Anniversary Edition, Part 2 June 2011 IN THIS ISSUE: THE COLIN STEELE SPECIAL COLIN STEELE REVIEWS THE FIELD OTHER CONTRIBUTORS: DITMAR (DICK JENSSEN) THE EDITOR PAUL ANDERSON LENNY BAILES DOUG BARBOUR WM BREIDING DAMIEN BRODERICK NED BROOKS HARRY BUERKETT STEPHEN CAMPBELL CY CHAUVIN BRAD FOSTER LEIGH EDMONDS TERRY GREEN JEFF HAMILL STEVE JEFFERY JERRY KAUFMAN PETER KERANS DAVID LAKE PATRICK MCGUIRE MURRAY MOORE JOSEPH NICHOLAS LLOYD PENNEY YVONNE ROUSSEAU GUY SALVIDGE STEVE SNEYD SUE THOMASON GEORGE ZEBROWSKI and many others SF COMMENTARY 81 40th Anniversary Edition, Part 2 CONTENTS 3 THIS ISSUE’S COVER 66 PINLIGHTERS Binary exploration Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) Stephen Campbell Damien Broderick 5 EDITORIAL Leigh Edmonds I must be talking to my friends Patrick McGuire The Editor Peter Kerans Jerry Kaufman 7 THE COLIN STEELE EDITION Jeff Hamill Harry Buerkett Yvonne Rousseau 7 IN HONOUR OF SIR TERRY Steve Jeffery PRATCHETT Steve Sneyd Lloyd Penney 7 Terry Pratchett: A (disc) world of Cy Chauvin collecting Lenny Bailes Colin Steele Guy Salvidge Terry Green 12 Sir Terry at the Sydney Opera House, Brad Foster 2011 Sue Thomason Colin Steele Paul Anderson Wm Breiding 13 Colin Steele reviews some recent Doug Barbour Pratchett publications George Zebrowski Joseph Nicholas David Lake 16 THE FIELD Ned Brooks Colin Steele Murray Moore Includes: 16 Reference and non-fiction 81 Terry Green reviews A Scanner Darkly 21 Science fiction 40 Horror, dark fantasy, and gothic 51 Fantasy 60 Ghost stories 63 Alternative history 2 SF COMMENTARY No. 81, June 2011, 88 pages, is edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough VIC 3088, Australia. -

Locus Awards Schedule

LOCUS AWARDS SCHEDULE WEDNESDAY, JUNE 24 3:00 p.m.: Readings with Fonda Lee and Elizabeth Bear. THURSDAY, JUNE 25 3:00 p.m.: Readings with Tobias S. Buckell, Rebecca Roanhorse, and Fran Wilde. FRIDAY, JUNE 26 3:00 p.m.: Readings with Nisi Shawl and Connie Willis. SATURDAY, JUNE 27 12:00 p.m.: “Amal, Cadwell, and Andy in Conversation” panel with Amal El- Mohtar, Cadwell Turnbull, and Andy Duncan. 1:00 p.m.: “Rituals & Rewards” with P. Djèlí Clark, Karen Lord, and Aliette de Bodard. 2:00 p.m.: “Donut Salon” (BYOD) panel with MC Connie Willis, Nancy Kress, and Gary K. Wolfe. 3:00 p.m.: Locus Awards Ceremony with MC Connie Willis and co-presenter Daryl Gregory. PASSWORD-PROTECTED PORTAL TO ACCESS ALL EVENTS: LOCUSMAG.COM/LOCUS-AWARDS-ONLINE-2020/ KEEP AN EYE ON YOUR EMAIL FOR THE PASSWORD AFTER YOU SIGN UP! QUESTIONS? EMAIL [email protected] LOCUS AWARDS TOP-TEN FINALISTS (in order of presentation) ILLUSTRATED AND ART BOOK • The Illustrated World of Tolkien, David Day (Thunder Bay; Pyramid) • Julie Dillon, Daydreamer’s Journey (Julie Dillon) • Ed Emshwiller, Dream Dance: The Art of Ed Emshwiller, Jesse Pires, ed. (Anthology Editions) • Spectrum 26: The Best in Contemporary Fantastic Art, John Fleskes, ed. (Flesk) • Donato Giancola, Middle-earth: Journeys in Myth and Legend (Dark Horse) • Raya Golden, Starport, George R.R. Martin (Bantam) • Fantasy World-Building: A Guide to Developing Mythic Worlds and Legendary Creatures, Mark A. Nelson (Dover) • Tran Nguyen, Ambedo: Tran Nguyen (Flesk) • Yuko Shimizu, The Fairy Tales of Oscar Wilde, Oscar Wilde (Beehive) • Bill Sienkiewicz, The Island of Doctor Moreau, H.G. -

An Evening to Honor Gene Wolfe

AN EVENING TO HONOR GENE WOLFE Program 4:00 p.m. Open tour of the Sanfilippo Collection 5:30 p.m. Fuller Award Ceremony Welcome and introduction: Gary K. Wolfe, Master of Ceremonies Presentation of the Fuller Award to Gene Wolfe: Neil Gaiman Acceptance speech: Gene Wolfe Audio play of Gene Wolfe’s “The Toy Theater,” adapted by Lawrence Santoro, accompanied by R. Jelani Eddington, performed by Terra Mysterium Organ performance: R. Jelani Eddington Closing comments: Gary K. Wolfe Shuttle to the Carousel Pavilion for guests with dinner tickets 8:00 p.m Dinner Opening comments: Peter Sagal, Toastmaster Speeches and toasts by special guests, family, and friends Following the dinner program, guests are invited to explore the collection in the Carousel Pavilion and enjoy the dessert table, coffee station and specialty cordials. 1 AN EVENING TO HONOR GENE WOLFE By Valya Dudycz Lupescu A Gene Wolfe story seduces and challenges its readers. It lures them into landscapes authentic in detail and populated with all manner of rich characters, only to shatter the readers’ expectations and leave them questioning their perceptions. A Gene Wolfe story embeds stories within stories, dreams within memories, and truths within lies. It coaxes its readers into a safe place with familiar faces, then leads them to the edge of an abyss and disappears with the whisper of a promise. Often classified as Science Fiction or Fantasy, a Gene Wolfe story is as likely to dip into science as it is to make a literary allusion or religious metaphor. A Gene Wolfe story is fantastic in all senses of the word. -

The (Ir)Relevance of Science Fiction to Non-Binary and Genderqueer

2018, Vol. 15 (1), 51–67(138) Anamarija Šporčič revije.ff.uni-lj.si/elope University of Ljubljana, Slovenia doi: 10.4312/elope.15.1.51-67 UDC: 82.09-311.9:305 The (Ir)Relevance of Science Fiction to Non-Binary and Genderqueer Readers ABSTRACT As an example of Jean Baudrillard’s third order of simulacra, contemporary science fiction represents a convenient literary platform for the exploration of our current and future understanding of gender, gender variants and gender fluidity. The genre should, in theory, have the advantage of being able to avoid the limitations posed by cultural conventions and transcend them in new and original ways. In practice, however, literary works of science fiction that are not subject to the dictations of the binary understanding of gender are few and far between, as authors overwhelmingly use the binary gender division as a binding element between the fictional world and that of the reader. The reversal of gender roles, merging of gender traits, androgynous characters and genderless societies nevertheless began to appear in the 1960s and 1970s. This paper briefly examines the history of attempts at transcending the gender binary in science fiction, and explores the possibility of such writing empowering non-binary/genderqueer individuals. Keywords: gender studies; science fiction; non-binary gender identities; reader response; genderqueer; gender fluidity; gender variants; gendered narrative (I)relevantnost znanstvene fantastike za nebinarno in kvirovsko bralstvo PovzeTEK Sodobna znanstvena fantastika, kot primer Baudrillardovega tretjega reda simulakra, predstavlja prikladno literarno podstat za raziskovanje našega trenutnega in bodočega razumevanja spola, spolne raznolikosti ter fluidnosti. V teoriji ima žanr prednost pred ostalimi, saj ni omejen z druž- benimi in kulturnimi pričakovanji, temveč jih ima možnost presegati na nove in izvirne načine. -

The Convention Itself

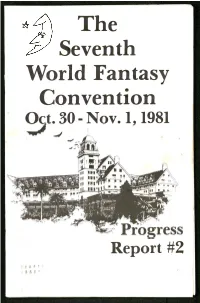

The Seventh World Fantasy Convention Oct. 30 - Nov. 1.1981 V ■ /n Jg in iiiWjF. ni III HITV Report #2 I * < ? I fl « f Guests of Honor Alan Garner Brian Frond Peter S. Beagle Master of Ceremonies Karl Edward Wagner Jack Rems, Jeff Frane, Chairmen Will Stone, Art Show Dan Chow, Dealers Room Debbie Notkin, Programming Mark Johnson, Bill Bow and others 1981 World Fantasy Award Nominations Life Achievement: Joseph Payne Brennan Avram Davidson L. Sprague de Camp C. L. Moore Andre Norton Jack Vance Best Novel: Ariosto by Chelsea Quinn Yarbro Firelord by Parke Godwin The Mist by Stephen King (in Dark Forces) The Shadow of the Torturer by Gene Wolfe Shadowland by Peter Straub Best Short Fiction: “Cabin 33” by Chelsea Quinn Yarbro (in Shadows 3) “Children of the Kingdom” by T.E.D. Klein (in Dark Forces) “The Ugly Chickens” by Howard Waldrop (in Universe 10) “Unicorn Tapestry” by Suzy McKee Charnas (in New Dimensions 11) Best Anthology or Collection: Dark Forces ed. by Kirby McCauley Dragons of Light ed. by Orson Scott Card Mummy! A Chrestomathy of Crypt-ology ed. by Bill Pronzini New Terrors 1 ed. by Ramsey Campbell Shadows 3 ed. by Charles L. Grant Shatterday by Harlan Ellison Best Artist: Alicia Austin Thomas Canty Don Maitz Rowena Morrill Michael Whelan Gahan Wilson Special Award (Professional) Terry Carr (anthologist) Lester del Rey (Del Rey/Ballantine Books) Edward L. Ferman (Magazine of Fantasy ir Science Fiction) David G. Hartwell (Pocket/Timescape/Simon & Schuster) Tim Underwood/Chuck Miller (Underwood & Miller) Donald A. Wollheim (DAW Books) Special Award (Non-professional) Pat Cadigan/Arnie Fenner (for Shayol) Charles de Lint/Charles R. -

Ourth Street Antasy Convention

Diana Wynne Jones 1991 Guest of Honor Tom Doherty A convention for students and 1991 Guest Publisher practitioners of the fantasy arts June 21st-23rd, 1991 Previous Guests: at the Roger Zelazny Sheraton Park Place Hotel Thomas Canty Minneapolis, Minnesota Jane Yolen Patricia McKillip Do you like books, thought-provoking panels, and Terri Winching intelligent conversation lasting well into the night? Do you have a special interest in the literature of the Robert Gould fantastic? Do you like good music, good food, and good parties? This is the convention for you! John Crowley Fourth Street is a small convention for people who are David Hartwell serious about good fantasy and good books — serious The Committee: about reading them, serious about writing them, Tim Powers serious about appreciating them in all their various Beth Meacham Chairman, forms. It's also for people who are serious about Registration: having a good time. It's two day of high-quii /, high- David Dyer-Bennet intensity, mind-stretching fun, focused on bo -- no Samuel R. Delany Treasurer, Parties: masquerade, no film or video program, no gi mg. Don Maitz Martin Schafer Hotel: Typical panel topics range from the sublime I the Rob Ihinger frivolous, from the uses of symbolism in fantasy to the Promotion: symbolism of shoes in fantasy, from subtext to Patricia C. Wrede developing taste. The always controversial Moral Programming: Fiction panel is a perennial favorite. Come and argue Steve Brust for yourself! Elise Krueger To pre-register, send your check for $22 to Fourth Street Eileen Lufkin Fantasy Convention, 4242 Minnehaha Avenue South, Art Show: Minneapolis, MN 55406 before June 1st, 1991, or Beth Friedman register at the door for $35. -

Epistolary Encounters: Diary and Letter Pastiche in Neo-Victorian Fiction

Epistolary Encounters: Diary and Letter Pastiche in Neo-Victorian Fiction By Kym Michelle Brindle Thesis submitted in fulfilment for the degree of PhD in English Literature Department of English and Creative Writing Lancaster University September 2010 ProQuest Number: 11003475 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11003475 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This thesis examines the significance of a ubiquitous presence of fictional letters and diaries in neo-Victorian fiction. It investigates how intercalated documents fashion pastiche narrative structures to organise conflicting viewpoints invoked in diaries, letters, and other addressed accounts as epistolary forms. This study concentrates on the strategic ways that writers put fragmented and found material traces in order to emphasise such traces of the past as fragmentary, incomplete, and contradictory. Interpolated documents evoke ideas of privacy, confession, secrecy, sincerity, and seduction only to be exploited and subverted as writers idiosyncratically manipulate epistolary devices to support metacritical agendas. Underpinning this thesis is the premise that much literary neo-Victorian fiction is bound in an incestuous relationship with Victorian studies.